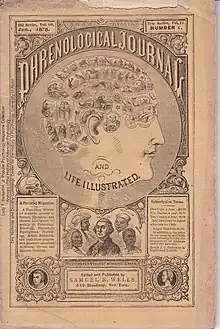

The Phrenological Journal

The American Phrenological Journal[upper-alpha 1] was a periodical in the United States devoted to the racist pseudoscience of phrenology, a collection of theories correlating skull features to personality and intelligence. The newspaper was founded in 1838 and dissolved in 1911. It was supported by the phrenologist Fowler family, who published it under the auspices of the Fowler & Wells Company. Several prominent historical figures underwent phrenological analyses by the Fowlers and the findings published in the journal; these include abolitionist Lydia Maria Child and writer Mark Twain.

History

The American Phrenological Journal and Miscellany was founded in 1838 as a phrenological periodical, though the details of its foundation are largely unknown.[2]: 73 It was financially and ideologically supported by the phrenologist Fowler family, including Orson Squire Fowler, Lorenzo Fowler, and Samuel R. Wells; Wells became its leading editor during the 1870s.[2]: 73 It was published by Fowler & Wells Company,[4] and it attributed the rise of interest in phrenology during the 1830s to Johann Spurzheim and George Combe.[5]: 178

In its first issue, the journal explained that its purpose was support the theories underlying phrenology – a pseudoscientific and racist area of research correlating skull measurements to personality and intelligence – and to apply them.[2]: 72–73, 78 It was an eclectic periodical; in addition to its phrenological research, it acquired and published writing in the domains of medical science, physiognomy, and in some unrelated areas, such as education.[2]: 73 During its early years, it had a circulation of around 20,000 subscribers, each paying $1 per year (increased to $1.50 per year during the Civil War).[2]: 73–74 It was among the most popular and authoritative publications in the field of phrenology during this time.[6]: 46 Though phrenology was deeply steeped in racism, an article republished in 1847 was relatively progressive in tone: Descendants of Africans were able to possess "as good a brain [...] as would be possessed by any white, under the same circumstances", if they so desired and continually worked to foster intellectual development.[5]: 179–180

In the late 1890s, Jessie A. Fowler became the editor of the journal.[6]: 62 It dissolved in 1911.[2]: 73

Persons analyzed

- In 1839, the Fowlers conducted a phrenological analysis of Black Hawk, a Sauk leader, concluding that his skull indicated he was a violent, destructive, and malevolent figure.[3]

- That same year, Lorenzo Fowler conducted a phrenological analysis of Cinqué, a key figure in the rebellion onboard the slave ship La Amistad, while he was awaiting trial. He concluded that Cinqué had phrenological attributes that signaled power and leadership, and an intelligence "superior to the majority of negroes' in our own country". The Fowlers later sold busts of Cinqué and republished the story in 1840.[7]

- In September 1841, the Fowlers conducted a phrenological analysis of Lydia Maria Child, a writer and abolitionist who edited the National Anti-Slavery Standard. They concluded she sought to "bring about moral, social, and intellectual reforms" because of her dissatisfaction with the world. Abolitionists and their publications, including the Liberator, began to accept phrenology as a useful science in their political reform projects.[8]

- In 1901, a phrenological analysis of American writer Mark Twain was published in the journal; it concluded he was determined and of a nervous temperament. Jessie A. Fowler likely wrote it.[6]: 62

Notes

References

- Bittel, Carla (2013). "Woman, know thyself: Producing and using phrenological knowledge in 19th-century America". Centaurus. 55 (2): 104–130. doi:10.1111/1600-0498.12015.

- Gibbons, Michelle E. (2009). "'Voices from the people': Letters to the American Phrenological Journal, 1854–1864". Journalism History. 35 (2): 72–81. doi:10.1080/00947679.2009.12062787. S2CID 197745215.

- Coleman, Cynthia-Lou (2020). "Black Hawk's skull". Clashes on Native American land: Framing environmental and scientific disputes. Palgrave Studies in Media and Environmental Communication. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 9783030341060.

- Stern, Madeleine B. (1980). "Margaret Fuller and the phrenologist-publishers". Studies in the American Renaissance. 229: 229–237. JSTOR 30228171. PMID 11636034.

- Hamilton, Cynthia S. (2008). "'Am I not a man and a brother?': Phrenology and anti-slavery". Slavery & Abolition. 29 (2): 173–187. doi:10.1080/01440390802027780. S2CID 145276656.

- Gribben, Alan (1972). "Mark Twain, phrenology, and the 'temperaments': A study of pseudoscientific influence". American Quarterly. 24 (1): 45–68. doi:10.2307/2711914. JSTOR 2711914. PMID 11634496.

- Branson, Susan (2017). "Phrenology and the science of race in antebellum America". Early American Studies. 15 (1): 164–193. doi:10.1353/eam.2017.0005. JSTOR 90000339. S2CID 152210042.

- Foster, Travis M. (2010). "Grotesque sympathy: Lydia Maria Child, white reform, and the embodiment of urban space". ESQ: A Journal of the American Renaissance. 51 (1): 1–32. doi:10.1353/esq.0.0045. S2CID 162305955.