Physical paradox

A physical paradox is an apparent contradiction in physical descriptions of the universe. While many physical paradoxes have accepted resolutions, others defy resolution and may indicate flaws in theory. In physics as in all of science, contradictions and paradoxes are generally assumed to be artifacts of error and incompleteness because reality is assumed to be completely consistent, although this is itself a philosophical assumption. When, as in fields such as quantum physics and relativity theory, existing assumptions about reality have been shown to break down, this has usually been dealt with by changing our understanding of reality to a new one which remains self-consistent in the presence of the new evidence.

Paradoxes relating to false assumptions

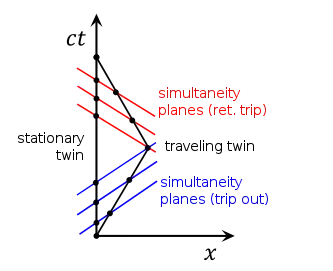

Certain physical paradoxes defy common sense predictions about physical situations. In some cases, this is the result of modern physics correctly describing the natural world in circumstances which are far outside of everyday experience. For example, special relativity has traditionally yielded two common paradoxes: the twin paradox and the ladder paradox. Both of these paradoxes involve thought experiments which defy traditional common sense assumptions about time and space. In particular, the effects of time dilation and length contraction are used in both of these paradoxes to create situations which seemingly contradict each other. It turns out that the fundamental postulate of special relativity that the speed of light is invariant in all frames of reference requires that concepts such as simultaneity and absolute time are not applicable when comparing radically different frames of reference.

Another paradox associated with relativity is Supplee's paradox which seems to describe two reference frames that are irreconcilable. In this case, the problem is assumed to be well-posed in special relativity, but because the effect is dependent on objects and fluids with mass, the effects of general relativity need to be taken into account. Taking the correct assumptions, the resolution is actually a way of restating the equivalence principle.

Babinet's paradox is that contrary to naïve expectations, the amount of radiation removed from a beam in the diffraction limit is equal to twice the cross-sectional area. This is because there are two separate processes which remove radiation from the beam in equal amounts: absorption and diffraction.

Similarly, there exists a set of physical paradoxes that directly rely on one or more assumptions that are incorrect. The Gibbs paradox of statistical mechanics yields an apparent contradiction when calculating the entropy of mixing. If the assumption that the particles in an ideal gas are indistinguishable is not appropriately taken into account, the calculated entropy is not an extensive variable as it should be.

Olbers' paradox shows that an infinite universe with a uniform distribution of stars necessarily leads to a sky that is as bright as a star. The observed dark night sky can be alternatively resolvable by stating that one of the two assumptions is incorrect. This paradox was sometimes used to argue that a homogeneous and isotropic universe as required by the cosmological principle was necessarily finite in extent, but it turns out that there are ways to relax the assumptions in other ways that admit alternative resolutions.

Mpemba paradox is that under certain conditions, hot water will freeze faster than cold water even though it must pass through the same temperature as the cold water during the freezing process. This is a seeming violation of Newton's law of cooling but in reality it is due to non-linear effects that influence the freezing process. The assumption that only the temperature of the water will affect freezing is not correct.

Paradoxes relating to unphysical mathematical idealizations

A common paradox occurs with mathematical idealizations such as point sources which describe physical phenomena well at distant or global scales but break down at the point itself. These paradoxes are sometimes seen as relating to Zeno's paradoxes which all deal with the physical manifestations of mathematical properties of continuity, infinitesimals, and infinities often associated with space and time. For example, the electric field associated with a point charge is infinite at the location of the point charge. A consequence of this apparent paradox is that the electric field of a point-charge can only be described in a limiting sense by a carefully constructed Dirac delta function. This mathematically inelegant but physically useful concept allows for the efficient calculation of the associated physical conditions while conveniently sidestepping the philosophical issue of what actually occurs at the infinitesimally-defined point: a question that physics is as yet unable to answer. Fortunately, a consistent theory of quantum electrodynamics removes the need for infinitesimal point charges altogether.

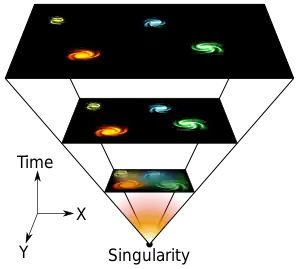

A similar situation occurs in general relativity with the gravitational singularity associated with the Schwarzschild solution that describes the geometry of a black hole. The curvature of spacetime at the singularity is infinite which is another way of stating that the theory does not describe the physical conditions at this point. It is hoped that the solution to this paradox will be found with a consistent theory of quantum gravity, something which has thus far remained elusive. A consequence of this paradox is that the associated singularity that occurred at the supposed starting point of the universe (see Big Bang) is not adequately described by physics. Before a theoretical extrapolation of a singularity can occur, quantum mechanical effects become important during the Planck era. Without a consistent theory, there can be no meaningful statement about the physical conditions associated with the universe before this point.

Another paradox due to mathematical idealization is D'Alembert's paradox of fluid mechanics. When the forces associated with two-dimensional, incompressible, irrotational, inviscid steady flow across a body are calculated, there is no drag. This is in contradiction with observations of such flows, but as it turns out a fluid that rigorously satisfies all the conditions is a physical impossibility. The mathematical model breaks down at the surface of the body, and new solutions involving boundary layers have to be considered to correctly model the drag effects.

Quantum mechanical paradoxes

A significant set of physical paradoxes are associated with the privileged position of the observer in quantum mechanics.

Three of the most famous of these are:

- the double-slit experiment;

- the EPR paradox and

- the Schrödinger's cat paradox,

all of them proposed as thought experiments relevant to the discussions of the correct interpretation of quantum mechanics.

These thought experiments try to use principles derived from the Copenhagen interpretation of quantum mechanics to derive conclusions that are seemingly contradictory. In the case of Schrödinger's cat this takes the form of a seeming absurdity.

A cat is placed in a box sealed off from observation with a quantum mechanical switch designed to kill the cat when appropriately deployed. While in the box, the cat is described as being in a quantum superposition of "dead" and "alive" states, though opening the box effectively collapses the cat's wave function to one of the two conditions. In the case of the EPR paradox, quantum entanglement appears to allow for the physical impossibility of information transmitted faster than the speed of light, violating special relativity. Related to the EPR paradox is the phenomenon of quantum pseudo-telepathy in which parties who are prevented from communicating do manage to accomplish tasks that seem to require direct contact.

The "resolutions" to these paradoxes are considered by many to be philosophically unsatisfying because they hinge on what is specifically meant by the measurement of an observation or what serves as an observer in the thought experiments. In a real physical sense, no matter what way either of those terms are defined, the results are the same. Any given observation of a cat will yield either one that is dead or alive; the superposition is a necessary condition for calculating what is to be expected, but will never itself be observed. Likewise, the EPR paradox yields no way of transmitting information faster than the speed of light; though there is a seemingly instantaneous conservation of the quantum-entangled observable being measured, it turns out that it is physically impossible to use this effect to transmit information. Why there is an instantaneous conservation is the subject of which is the correct interpretation of quantum mechanics.

Speculative theories of quantum gravity that combine general relativity with quantum mechanics have their own associated paradoxes that are generally accepted to be artifacts of the lack of a consistent physical model that unites the two formulations. One such paradox is the black hole information paradox which points out that information associated with a particle that falls into a black hole is not conserved when the theoretical Hawking radiation causes the black hole to evaporate. In 2004, Stephen Hawking claimed to have a working resolution to this problem, but the details have yet to be published and the speculative nature of Hawking radiation means that it isn't clear whether this paradox is relevant to physical reality.

Causality paradoxes

A set of similar paradoxes occurs within the area of physics involving arrow of time and causality. One of these, the grandfather paradox, deals with the peculiar nature of causality in closed time-like loops. In its most crude conception, the paradox involves a person traveling back in time and murdering an ancestor who hadn't yet had a chance to procreate. The speculative nature of time travel to the past means that there is no agreed upon resolution to the paradox, nor is it even clear that there are physically possible solutions to the Einstein equations that would allow for the conditions required for the paradox to be met. Nevertheless, there are two common explanations for possible resolutions for this paradox that take on similar flavor for the explanations of quantum mechanical paradoxes. In the so-called self-consistent solution, reality is constructed in such a way as to deterministically prevent such paradoxes from occurring. This idea makes many free will advocates uncomfortable, though it is very satisfying to many philosophical naturalists. Alternatively, the many worlds idealization or the concept of parallel universes is sometimes conjectured to allow for a continual fracturing of possible worldlines into many different alternative realities. This would mean that any person who traveled back in time would necessarily enter a different parallel universe that would have a different history from the point of the time travel forward.

Another paradox associated with the causality and the one-way nature of time is Loschmidt's paradox which poses the question how can microprocesses that are time-reversible produce a time-irreversible increase in entropy. A partial resolution to this paradox is rigorously provided for by the fluctuation theorem which relies on carefully keeping track of time averaged quantities to show that from a statistical mechanics point of view, entropy is far more likely to increase than to decrease. However, if no assumptions about initial boundary conditions are made, the fluctuation theorem should apply equally well in reverse, predicting that a system currently in a low-entropy state is more likely to have been at a higher-entropy state in the past, in contradiction with what would usually be seen in a reversed film of a nonequilibrium state going to equilibrium. Thus, the overall asymmetry in thermodynamics which is at the heart of Loschmidt's paradox is still not resolved by the fluctuation theorem. Most physicists believe that the thermodynamic arrow of time can only be explained by appealing to low entropy conditions shortly after the Big Bang, although the explanation for the low entropy of the Big Bang itself is still debated.

Observational paradoxes

A further set of physical paradoxes are based on sets of observations that fail to be adequately explained by current physical models. These may simply be indications of the incompleteness of current theories. It is recognized that unification has not been accomplished yet which may hint at fundamental problems with the current scientific paradigms. Whether this is the harbinger of a scientific revolution yet to come or whether these observations will yield to future refinements or be found to be erroneous is yet to be determined. A brief list of these yet inadequately explained observations includes observations implying the existence of dark matter, observations implying the existence of dark energy, the observed matter-antimatter asymmetry, the GZK paradox, the heat death paradox, and the Fermi paradox.

See also

References

- Bondi, Hermann (1980). Relativity and Common Sense. Dover Publications. p. 177. ISBN 0-486-24021-5.

- Geroch, Robert (1981). General Relativity from A to B. University Of Chicago Press. p. 233. ISBN 0-226-28864-1.

- Gott, J. Richard (2002). Time Travel in Einstein's Universe. Mariner Books. p. 291. ISBN 0-395-95563-7.

- Gamow, George (1993). Mr Tompkins in Paperback (reissue ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 202. ISBN 0-521-44771-2.

- Feynman, Richard P. (1988). QED: The Strange Theory of Light and Matter. Princeton University Press. p. 176. ISBN 0-691-02417-0.

- Ford, Kenneth W. and Paul Hewitt (2004). The Quantum World : Quantum Physics for Everyone. Harvard University Press. p. 288. ISBN 0-674-01342-5.

- Tributsch, Helmut (2015). Irrationality in Nature or in Science? Probing a Rational Energy and Mind World. CreateSpace. p. 217. ISBN 978-1514724859.