Pickpocketing

Pickpocketing is a form of larceny that involves the stealing of money or other valuables from the person or a victim's pocket without them noticing the theft at the time. It may involve considerable dexterity and a knack for misdirection. A thief who works in this manner is known as a pickpocket.

As an occupation

Pickpockets and other thieves, especially those working in teams, sometimes apply distraction, such as asking a question or bumping into the victim. These distractions sometimes require sleight of hand, speed, misdirection and other types of skills.[1][2]

Pickpockets may be found in any crowded place around the world. However, Barcelona and Rome have been noted as being particularly dangerous pickpocket havens.[3][4] Thieves have been known to operate in high traffic areas such as mass transit stations, even boarding subway trains so they can use the distractions of crowds and sudden stop-and-go movements from the train to steal from others. As soon as the thieves have what they want, they simply get off at the next stop leaving the victim unable to figure out who robbed them and when.

As entertainment

Pickpocketing skills are employed by some magicians as a form of entertainment, either by taking an item from a spectator or by returning it without them knowing they had lost it. Borra, arguably the most famous stage pickpocket of all time, became the highest-paid European performer in circuses during the 1950s. For 60 years he was billed as "the King of Pickpockets" and encouraged his son, Charly, to follow in his cunning trade, his offspring being billed as "the Prince of Pickpockets".[5] Henri Kassagi, a French-Tunisian illusionist, acted as technical advisor on Robert Bresson's 1959 film Pickpocket and appeared as instructor and accomplice to the main character. British entertainer James Freedman created the pickpocket sequences for the 2005 film Oliver Twist directed by Roman Polanski.[6] American illusionist David Avadon featured pickpocketing as his trademark act for more than 30 years and promoted himself as "a daring pickpocket with dashing finesse" and "the country's premier exhibition pickpocket, one of the few masters in the world of this underground art."[7][8] According to Thomas Blacke, an American illusionist who holds several world records, it has become more difficult nowadays to pickpocket both in the streets and on the stage because the general population wears less, or lighter, clothing.[9] In 2015 an artist hired a pickpocket to distribute sculptures at Frieze Art Fair in New York.[10]

Methods

Pickpocketing often requires different levels of skill, relying on a mixture of sleight of hand and misdirection. To get the proper misdirect or distraction, pickpockets will normally use the distracting environment that crowds offer or create situations using accomplices. Pickpocketing still thrives in Europe and other countries that are high in tourism. It's most common in areas with large crowds. Sometimes pickpockets put signs up that warn tourist to watch for pickpockets. This causes people to worry and quickly check if their valuables are still on them, thereby showing pickpockets exactly where their valuables are. Once a pickpocket finds a person they want to steal from, often called a "mark" or a victim, the pickpocket will then create or look for an opportunity to steal.[11]

The most common methods used by modern-day pickpockets are:

- Driving by and snatching a passerby's items. This method is common in cities like London where mopeds are a common way to travel.

- Offering to help someone with their luggage, then proceeding to disappear in a crowded area. This method works well because it gives the victim a false sense of trust with the pickpocketer.

- The next technique involves a team of three or more people and a crowded area. After finding their mark, two of the pickpockets slow down while walking in front of their mark appearing as a lost couple. Meanwhile, the mark is stuck behind them and their accomplice goes through the mark's bag unnoticed.

- Using large crowds where there is a small doorway, like that in trains, forcing the crowd to squeeze together to get through. A pickpocket uses this opportunity to stick their hands into peoples' pockets and go unnoticed.

- Using a stooge, a fake couple, or group goes up and ask the mark for help. For example, it can be to take their photo, hold their bag, or just simply asking for directions and getting them to hold a map. As this is happening their partner is going through the mark's bags while they are distracted helping.

- Using a child to pickpocket or as a distraction is common in many countries.

- The bump is the most famous of all the ways and is often used in movies. It is where the pickpocket bumps into the mark inconspicuously, allowing them to access the mark's pockets. The bump usually requires expert sleight of hand.

- Another common technique is so-called the "slash and grab"; the pickpocket cuts a purse or bag strap without the mark's knowledge and makes off with the bag. They can then take the contents and leave behind the bag and any form of identification in the trash or a back alley.[12]

Famous pickpockets

Famous fictional pickpockets include the Artful Dodger and Fagin, characters from the Charles Dickens' 1838 novel Oliver Twist. Famous true-life historical pickpockets include the Irish prostitute Chicago May, who was profiled in books; Mary Frith, nicknamed Moll Cutpurse; the Gubbins band of highwaymen; and Cutting Ball, a notorious Elizabethan thief. George Barrington's escapades, arrests, and trials, were widely chronicled in the late 18th-century London press.

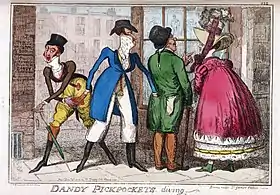

Pickpocketing in the 17th and 18th centuries

The 17th and 18th centuries saw a significant number of men and women pickpockets, operating in public and/or private places and stealing different types of items. Some of those pickpockets were caught and prosecuted for their theft, however, in most cases, they managed to avoid punishment (whether they were skilful enough not to get caught or they were acquitted in Court). Although we refer to them as "pickpockets" today, this is not necessarily how they were called in the 17th century: they were sometimes referred to as "cut-purses", as can be seen in some 17th-century ballads.[13]

At the time, pockets were not yet sewn to clothes, as they are today. This means that pockets were a little purse that people wore close to their body. This was especially true for women, since men's pockets were sewn "into the linings of their coats".[14] Women's pockets were worn beneath a piece of clothing, and not "as opposed to pouches or bags hanging outside their clothes".[15] These external pockets were still in fashion until the mid-19th century.[15]

Gender

Pickpocketing in the 18th century was committed by both men and women (looking at prosecuted cases of pickpocketing, it appears that there were more female defendants than male.)[16] Along with shoplifting, pickpocketing was the only type of crime committed by more women than men.[17] It seems that in the 18th century, most pickpockets stole out of economic needs: they were often poor and did not have any economic support,[18] and unemployment was "the single most important cause of poverty",[19] leading the most needy ones to pick pockets.

In most cases, pickpockets operated depending on the opportunities they got: if they saw someone wearing a silver watch or with a handkerchief bulging out of their pocket, the pickpockets took the item. This means that the theft was, in such cases, not premeditated. However, some pickpockets did work as a gang, in which cases they planned thefts, even though they could not be sure of what they would get (Defoe's Moll Flanders[20] gives several examples of how pickpockets worked as a team or on their own, when the eponymous character becomes a thief out of need).

The prosecutions against pickpockets at the Old Bailey between 1780 and 1808 show that male pickpockets were somewhat younger than female ones: 72% of men pickpockets convicted at the time were aged from under 20 to 30, while 72% of women convicted of picking pockets were aged between 20 and 40.[16] One reason that may explain why women pickpockets were older is that most of women pickpockets were prostitutes (this explains why very few women under 20 years old were convicted for picking pockets). At the end of the 18th century, 76% of women defendants were prostitutes, and as a result, the victims of pickpockets were more often men than women.[16]

In most cases, these prostitutes would lay with men (who were frequently drunk), and take advantage of the situation to steal from these clients. Men who were robbed by prostitutes often chose not to prosecute the pickpockets, since they would have had to acknowledge their "immoral behaviour".[19] The few men who decided to prosecute prostitutes for picking their pockets were often mocked in Court, and very few prostitutes ended up being declared fully guilty.[16]

The men who were prosecuted for picking pockets and who were under 20 years old were often children working in gangs, under the authority of an adult who trained them to steal.[19] The children involved in these gangs were orphans (either because of having been abandoned or because their parents had died), and the whole relationship they had with the adult ruling the gang and the other children was that of a "surrogate family".[19] Charles Dickens' Oliver Twist provides a good example of how orphans were recruited and turned into street criminals.

Methods of operation and targets

Male and female pickpockets tended to operate in different locations: 80% of men operated in public areas while 78% of women operated in private places.[16] This can be explained by the fact that most female pickpockets were prostitutes, robbing their victims in their lodging after having lain with them. Male pickpockets, on the other hand, tended to operate in public places because they did not have the opportunity that prostitutes had.

The fact that men and women did not operate in the same places led to them stealing different types of items: men stole mostly handkerchiefs,[16] because they were one of the easiest items to take from someone without them noticing it. Women tended to steal watches (some pickpockets also stole watches in public places, but it was more difficult) and bags with money in them. When defending themselves in court, prostitutes often argued that the money had been a gift from the victim and managed to be acquitted, as the men prosecuting them were often drunk at the time of the theft and were not taken seriously by the court.[18]

Prosecution

In the eyes of British law, pickpocketing was considered a capital offence from 1565 on:[16] this meant that it was punishable by hanging.[19] However, for the crime to be considered as a capital offence, the stolen item had to be worth more than 12 pennies, otherwise it was considered to be petty larceny,[16] which meant that the thief would not be hanged. The 18th century law also stated that only the thief could be prosecuted—any accomplice or receiver of the stolen item could not be found guilty of the crime: "This meant that, if two people were indicted together, and there was not clear proof as to which one made the final act of taking, neither should be found guilty".[16]: 69

Moreover, in order to be able to prosecute someone for pickpocketing, the victim of the theft had to not be aware that they were being robbed. In 1782, a case at the Old Bailey made it clear that this was supposed to prevent people who had been robbed while they were drunk from prosecuting the defendant (in most of the cases that meant men who had been robbed by prostitutes):[16] The victims of pickpockets who were drunk at the time of the theft were considered to be partially responsible for being robbed.

Even though pickpockets were supposed to be hanged for their crime, this punishment, in fact, rarely happened: 61% of women accused of picking pockets were acquitted[19] and those who were not acquitted often managed to escape the capital sentence, as only 6% of defendants accused of pickpocketing between 1780 and 1808 were hanged.[16]

In the cases of prostitutes being accused of having pickpocketed male prosecutors, the jury's verdict was very often more favourable to the woman defendant than to the man prosecuting her.[16] Men who had been laying with prostitutes were frowned upon by the court. One of the reasons was that they had chosen to take off their clothes, they were also drunk most of the time, so they were considered responsible for being robbed. The other reason is that it was considered bad for a man to mix with a prostitute, which is why in many cases there was no prosecution: the victim was too ashamed of admitting that he had been with a prostitute.[16]

In those cases, since the jury was often inclined to despise the prosecutor and to side with the defendant, when they did not completely acquit the woman they often reached a partial verdict and this mostly meant transportation[16] to America (that is the case for Moll Flanders[20]), and to Australia later on.

See also

- School of Seven Bells – musical group named after a mythical pickpocket academy

- Blackguard Children – usually poor or homeless orphans who made a living through begging and pickpocketing

References

- Heap, Simon (December 1997). "'Jaguda boys': pickpocketing in Ibadan, 1930–60". Urban History. 24 (3): 324–343. doi:10.1017/S0963926800012384. JSTOR 44614007. S2CID 145130577.

- Heap, Simon (January 2010). "'Their Days are Spent in Gambling and Loafing, Pimping for Prostitutes, and Picking Pockets': Male Juvenile Delinquents on Lagos Island, 1920s–1960s". Journal of Family History. 35 (1): 48–70. doi:10.1177/0363199009348306. PMID 20099405. S2CID 24010849.

- "Italy - #1 for Pickpockets". WorldNomads.com. 11 March 2011. Archived from the original on 2011-03-14.

- "TripAdvisor Points Out Top 10 Places Worldwide to Beware Pickpockets". TripAdvisor. 10 September 2009. Retrieved 2019-09-18 – via PR Newswire.

- Nevil, D. (31 October 1998). "Obituary: Borra". The Independent. Archived from the original on 2022-05-26. Retrieved 2019-09-18.

- "How I learnt to pick a pocket (or two)". The Times. 6 October 2005. Retrieved 2019-09-18.

- Nelson, Valerie J. (4 September 2009). "David Avadon dies at 60; illusionist specialized in picking pockets". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 9 June 2012.

- "The Fastest Pickpocket in the West". DavidAvadon.com. Archived from the original on 2009-09-03.

- Law, Benjamin (Autumn 2012). "Pickpocketing: It's the Most Artful of All Criminal Acts, but Are People Who Pick Pockets Thriving or, like the Valuables They Target, Vanishing into Thin Air?" (PDF). Smith Journal. Vol. 2. pp. 29–31. Retrieved 2019-09-18.

- "Frieze Hired a Pickpocket to Roam Their Art Fair—Here's Why". The New York Observer. 5 May 2016.

- Williams, Caroline. "How pickpockets trick your mind". www.bbc.com. Retrieved 2020-09-20.

- "Outsmart pickpockets". www.scti.co.nz. Retrieved 2020-09-20.

- "EBBA 30274". ebba.english.ucsb.edu. UCSB English Broadside Ballad Archive. Retrieved 2015-11-25.

- "A history of pockets". vam.ac.uk. Victoria and Albert Museum. Retrieved 2015-11-25.

- Burnston, Sharon Ann (Spring 2001). "What's in a Pocket?". Historic New England. Archived from the original on 2015-10-28. Retrieved 2015-11-25.

- Palk, Deirdre (2006). "Pickpocketing". Gender, Crime and Judicial Discretion 1780–1830. Great Britain: The Boydell Press. pp. 67–88. ISBN 0-86193-282-X.

- "Historical Background - Gender in the Proceedings". Old Bailey Online. Retrieved 2015-11-05.

- Shoemaker, Robert (April 2010). "Print and the Female Voice: Representation of Women's Crime in London, 1690–1735". Gender & History. 22 (1): 75–91. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0424.2009.01579.x. S2CID 143952335.

- Hitchcock, Tim; Shoemaker, Robert (2010). Tales from the Hanging Court. Bloomsbury Academic. ISBN 978-0-340-91375-8.

- Defoe, Daniel (1722). Moll Flanders. England: Penguins Classic. ISBN 978-0-14-043313-5.

Further reading

- Avadon, David (2007). Cutting Up Touches: A Brief History of Pockets and the People Who Pick Them. Chicago: Squash Publishing. ISBN 978-0-9744681-6-7. Archived from the original on 2007-09-30. – about the history of theatrical pickpocketing.

- Columb, Frank (1999). Chicago May, Queen of the Blackmailers. Cambridge: Evod Academic Publishing Co. ASIN B007HF8KC6.

- King, Betty Nygaard (2001). Hell Hath No Fury: Famous Women in Crime. Ottawa: Borealis Press. ISBN 0-88887-262-3.

External links

- How Pickpockets Work (How Stuff Works)

- Ultimate Guide to Avoiding Pickpockets