Pickett's Charge

Pickett's Charge (July 3, 1863), also known as the Pickett–Pettigrew–Trimble Charge, was an infantry assault ordered by Confederate General Robert E. Lee against Major General George G. Meade's Union positions on the last day of the Battle of Gettysburg in Pennsylvania during the Civil War. Confederate troops made a frontal assault toward the center of Union lines, ultimately being repulsed with heavy casualties. Suffering from a lack of preparation and problems from the onset, the attack was a costly mistake that decisively ended Lee's invasion of the north and forced a retreat back to Virginia.[1]

| Pickett's Charge | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Battle of Gettysburg | |||||||

_(14596104027).jpg.webp) General Pickett's Famous Charge at Gettysburg drawn by A.R. Waud | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

George G. Meade Winfield S. Hancock (WIA) John Gibbon (WIA) Alexander Hays |

Robert E. Lee James Longstreet George Pickett J. Johnston Pettigrew (WIA) Isaac R. Trimble (WIA) | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

| ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 1,500 killed and wounded |

| ||||||

The charge is popularly named after Major General George Pickett, one of three Confederate generals (all under the command of Lieutenant General James Longstreet) who led the assault.

Pickett's Charge was part of Lee's "general plan"[2] to take Cemetery Hill and the network of roads it commanded. His military secretary, Armistead Lindsay Long, described Lee's thinking:

There was ... a weak point ... where [Cemetery Ridge], sloping westward, formed the depression through which the Emmitsburg road passes. Perceiving that by forcing the Federal lines at that point and turning toward Cemetery Hill [Hays' Division] would be taken in flank and the remainder would be neutralized. ... Lee determined to attack at that point, and the execution was assigned to Longstreet.[3]

Lee believed that, after Confederate attacks on both the left and right flanks of the Union lines on July 2, Meade would concentrate his defenses there to the detriment of his center. However, on the night of July 2, Meade correctly predicted to General John Gibbon, after a council of war, that Lee would attack the center of his lines the following morning and reinforced that area with additional soldiers and artillery.

The infantry assault was preceded by a massive artillery bombardment that was meant to soften up the Union defense and silence its artillery, but it was largely ineffective. Approximately 12,500 men in nine infantry brigades advanced over open fields for three-quarters of a mile (1200 m) under heavy Union artillery and rifle fire. Although some Confederates were able to breach the low stone wall that shielded many of the Union defenders, they could not maintain their hold and were repelled with over 50 percent casualties.

Often cited as one of the turning points of the war, the farthest point reached by the attack has been referred to as the high-water mark of the Confederacy.

Background

Military situation

Opposing forces

Union

Confederate

Plans and command structures

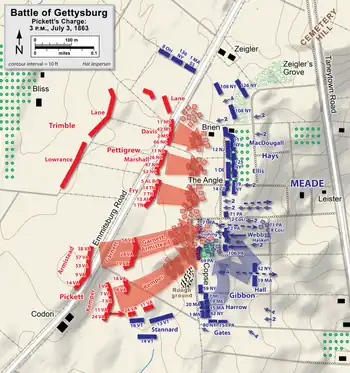

Pickett's Charge was planned for three Confederate divisions, commanded by Maj. Gen. George Pickett, Brig. Gen. J. Johnston Pettigrew, and Maj. Gen. Isaac R. Trimble, consisting of troops from Lt. Gen. James Longstreet's First Corps and Lt. Gen. A. P. Hill's Third Corps. Pettigrew commanded brigades from Maj. Gen. Henry Heth's old division, under Col. Birkett D. Fry (Archer's Brigade), Col. James K. Marshall (Pettigrew's Brigade), Brig. Gen. Joseph R. Davis, and Col. John M. Brockenbrough. Trimble, commanding Maj. Gen. Dorsey Pender's division, had the brigades of Brig. Gens. Alfred M. Scales (temporarily commanded by Col. William Lee J. Lowrance) and James H. Lane. Two brigades from Maj. Gen. Richard H. Anderson's division (Hill's Corps) were to support the attack on the right flank: Brig. Gen. Cadmus M. Wilcox and Col. David Lang (Perry's brigade).[4]

The target of the Confederate assault was the center of the Union Army of the Potomac's II Corps, commanded by Maj. Gen. Winfield S. Hancock. Directly in the center was the division of Brig. Gen. John Gibbon with the brigades of Brig. Gen. William Harrow, Col. Norman J. Hall, and Brig. Gen. Alexander S. Webb. On the night of July 2, Meade correctly predicted to Gibbon at a council of war that Lee would try an attack on Gibbon's sector the following morning.[5] To the north of this position were brigades from the division of Brig. Gen. Alexander Hays, and to the south was Maj. Gen. Abner Doubleday's division of the I Corps, including the 2nd Vermont Brigade of Brig. Gen. George J. Stannard and the 121st Pennsylvania under the command of Col. Chapman Biddle. Meade's headquarters were just behind the II Corps line, in the small house owned by the widow Lydia Leister.[4]

The specific objective of the assault has been the source of historical controversy. Traditionally, the "copse of trees" on Cemetery Ridge has been cited as the visual landmark for the attacking force. Historical treatments such as the 1993 film Gettysburg continue to popularize this view, which originated in the work of Gettysburg Battlefield historian John B. Bachelder in the 1880s. However, recent scholarship, including published works by some Gettysburg National Military Park historians, has suggested that Lee's goal was actually Ziegler's Grove on Cemetery Hill, a more prominent and highly visible grouping of trees about 300 yards (274 m) north of the copse.

The much-debated theory suggests that Lee's general plan for the second-day attacks (the seizure of Cemetery Hill) had not changed on the third day, and the attacks on July 3 were also aimed at securing the hill and the network of roads it commanded. The copse of trees, currently a prominent landmark, was under ten feet (3 m) high in 1863, visible to a portion of the attacking columns only from certain parts of the battlefield.[6]

From the beginning of the planning, things went awry for the Confederates. While Pickett's division had not been used yet at Gettysburg, A. P. Hill's health became an issue and he did not participate in selecting which of his troops were to be used for the charge. Some of Hill's corps had fought lightly on July 1 and not at all on July 2. However, troops that had done heavy fighting on July 1 ended up making the charge.[7]

Although the assault is known to popular history as Pickett's Charge, overall command was given to James Longstreet, and Pickett was one of his divisional commanders. Lee did tell Longstreet that Pickett's fresh division should lead the assault, so the name is appropriate, although some recent historians have used the name Pickett–Pettigrew–Trimble Assault (or, less frequently, Longstreet's Assault) to more fairly distribute the credit (or blame). With Hill sidelined, Pettigrew's and Trimble's divisions were delegated to Longstreet's authority as well. Thus, Pickett's name has been lent to a charge in which he commanded 3 out of the 11 brigades while under the supervision of his corps commander throughout.

Pickett's men were almost exclusively from Virginia, with the other divisions consisting of troops from North Carolina, Mississippi, Alabama, and Tennessee. The supporting troops under Wilcox and Lang were from Alabama and Florida.[8]

In conjunction with the infantry assault, Lee planned a cavalry action in the Union rear. Maj. Gen. J. E. B. Stuart led his cavalry division to the east, prepared to exploit Lee's hoped-for breakthrough by attacking the Union rear and disrupting its line of communications (and retreat) along the Baltimore Pike.[9]

Despite Lee's hope for an early start, it took all morning to arrange the infantry assault force. Neither Lee's nor Longstreet's headquarters sent orders to Pickett to have his division on the battlefield by daylight. Historian Jeffrey D. Wert blames this oversight on Longstreet, describing it either as a misunderstanding of Lee's oral order or a mistake.[10] Some of the many criticisms of Longstreet's Gettysburg performance by the postbellum Lost Cause authors cite this failure as evidence that Longstreet deliberately undermined Lee's plan for the battle.[11]

Meanwhile, on the far right end of the Union line, a seven-hour battle raged for the control of Culp's Hill. Lee's intent was to synchronize his offensive across the battlefield, keeping Meade from concentrating his numerically superior force, but the assaults were poorly coordinated and Maj. Gen. Edward "Allegheny" Johnson's attacks against Culp's Hill petered out just as Longstreet's cannonade began.[12]

Artillery barrage

The infantry charge was preceded by what Lee hoped would be a powerful and well-concentrated cannonade of the Union center, destroying the Union artillery batteries that could defeat the assault and demoralizing the Union infantry. But a combination of inept artillery leadership and defective equipment doomed the barrage from the beginning. Longstreet's corps artillery chief, Col. Edward Porter Alexander, had effective command of the field; Lee's artillery chief, Brig. Gen. William N. Pendleton, played little role other than to obstruct the effective placement of artillery from the other two corps. Despite Alexander's efforts, then, there was insufficient concentration of Confederate fire on the objective.[13]

The July 3 bombardment was likely the largest of the war,[14] with hundreds of cannons from both sides firing along the lines for one to two hours,[15] starting around 1 p.m. Confederate guns numbered between 150 and 170[16] and fired from a line over two miles (3 km) long, starting in the south at the Peach Orchard and running roughly parallel to the Emmitsburg Road. Confederate Brig. Gen. Evander M. Law wrote, "The cannonade in the center ... presented one of the most magnificent battle-scenes witnessed during the war. Looking up the valley towards Gettysburg, the hills on either side were capped with crowns of flame and smoke, as 300 guns, about equally divided between the two ridges, vomited their iron hail upon each other."[17]

Despite its ferocity, the fire was mostly ineffectual. Confederate shells often overshot the infantry front lines—in some cases because of inferior shell fuses that delayed detonation—and the smoke covering the battlefield concealed that fact from the gunners. Union artillery chief Brig. Gen. Henry J. Hunt had only about 80 guns available to conduct counter-battery fire; the geographic features of the Union line had limited areas for effective gun emplacement. He also ordered that firing cease to conserve ammunition, but to fool Alexander, Hunt ordered his cannons to cease fire slowly to create the illusion that they were being destroyed one by one. By the time all of Hunt's cannons ceased fire, and still blinded by the smoke from battle, Alexander fell for Hunt's deception and believed that many of the Union batteries had been destroyed. Hunt had to resist the strong arguments of Hancock, who demanded Union fire to lift the spirits of the infantrymen pinned down by Alexander's bombardment. Even Meade was affected by the artillery—the Leister house was a victim of frequent overshots, and he had to evacuate with his staff to Powers Hill. The counter-battery fire depleted the northern ammunition stocks, leaving them insufficient time to replenish before the southern assault. For the rest of his life, Hunt always maintained that had he been allowed to do what he'd intended—saved his long range shells for the attack he knew was coming, then bombarded the Confederate forces with every gun available once they lined up for their advance—the charge would never have happened and many northern lives would have been saved.[18]

_(14576199329).jpg.webp)

The day was hot, 87 °F (31 °C) by one account,[19] and humid, and the Confederates suffered under the hot sun and from the Union counter-battery fire as they awaited the order to advance. When Union cannoneers overshot their targets, they often hit the massed infantry waiting in the woods of Seminary Ridge or in the shallow depressions just behind Alexander's guns, causing significant casualties before the charge began.[20]

Longstreet had opposed the charge from the beginning, convinced the charge would fail (which ultimately proved true), and had his own plan that he would have preferred for a strategic movement around the Union left flank. In his memoirs, he recalled telling Lee:

General, I have been a soldier all my life. I have been with soldiers engaged in fights by couples, by squads, companies, regiments, divisions, and armies, and should know, as well as any one, what soldiers can do. It is my opinion that no fifteen thousand men ever arrayed for battle can take that position.[21]

Longstreet wanted to avoid personally ordering the charge by attempting to pass the mantle onto young Colonel Alexander, telling him that he should inform Pickett at the optimum time to begin the advance, based on his assessment that the Union artillery had been effectively silenced. Although he hadn't become aware of such a development, Alexander eventually notified Pickett that he was running dangerously short of ammunition, sending the message "If you are coming at all, come at once, or I cannot give you proper support, but the enemy's fire has not slackened at all. At least eighteen guns are still firing from the cemetery itself." Pickett asked Longstreet, "General, shall I advance?" Longstreet recalled in his memoirs, "The effort to speak the order failed, and I could only indicate it by an affirmative bow."[22]

Longstreet made one final attempt to call off the assault. After his encounter with Pickett, he discussed the artillery situation with Alexander, and was informed that Alexander did not have full confidence that all the enemy's guns were silenced, and that the Confederate ammunition was almost exhausted. Longstreet ordered Alexander to stop Pickett, but the young colonel explained that replenishing his ammunition from the trains in the rear would take over an hour, and this delay would nullify any advantage the previous barrage had given them. The infantry assault went forward without the Confederate artillery close support that had been originally planned.[23]

Infantry assault

The entire force that stepped off toward the Union positions at about 2 p.m.[15] comprised about 12,500 men.[24] Although the attack is popularly called a "charge", the men marched deliberately in line, prepared to speed up and charge only when they were within a few hundred yards of the enemy. The line consisted of Pettigrew and Trimble on the left, and Pickett to the right. The nine brigades of men stretched over a mile-long (1,600 m) front. The Confederates immediately encountered heavy artillery fire and were slowed by fences in their path. Fire from Lt. Col. Freeman McGilvery's concealed artillery positions north of Little Round Top raked the Confederate right flank, artillery fire from Cemetery Hill hit the left, while the center faced the cannons of the II Corps with the Union artillery reserve in a second line behind. The ground between Seminary Ridge and Cemetery Ridge is slightly undulating, and the advancing troops periodically disappeared from the view of the Union cannoneers while advancing the nearly three quarters of a mile across open fields to reach the Union line.

As the three Confederate divisions advanced, awaiting Union soldiers began shouting "Fredericksburg! Fredericksburg! Fredericksburg!" in reference to the disastrous Union advance on the Confederate line during the 1862 Battle of Fredericksburg.[25] Shell and solid shot in the beginning turned to canister and musket fire as the Confederates came within 400 yards of the Union line. At this point Confederate unit cohesion and morale began to break down. The last shelter before reaching the Union lines lay at 300 yards, in the sunken depression of the Emmitsburg Road. Thousands of Confederates took to the ground there and refused to advance any further, many surrendering to Union troops after the battle.[26] Over 2/3rds of the initial force may have failed to make the final charge; at contact the mile-long front had shrunk to less than half a mile, as the men filled in gaps that appeared throughout the line and followed the natural tendency to move away from the flanking fire.[27][28]

On the left flank of the attack, Brockenbrough's brigade was devastated by artillery fire from Cemetery Hill. They were also subjected to a surprise musket fusillade from the 8th Ohio Infantry regiment. The 160 Ohioans, firing from a single line, so surprised Brockenbrough's Virginians—already demoralized by their losses to artillery fire—that they panicked and fled back to Seminary Ridge, crashing through Trimble's division and causing many of his men to bolt as well. The Ohioans followed up with a successful flanking attack on Davis's brigade of Mississippians and North Carolinians, which was now the left flank of Pettigrew's division. The survivors were subjected to increasing artillery fire from Cemetery Hill. More than 1,600 rounds were fired at Pettigrew's men during the assault. This portion of the assault never advanced much farther than the sturdy fence at the Emmitsburg Road. By this time, the Confederates were close enough to be fired on by artillery canister and Alexander Hays' division unleashed very effective musketry fire from behind 260 yards of stone wall, with every rifleman of the division lined up as many as four deep, exchanging places in line as they fired and then fell back to reload.[29]

They were at once enveloped in a dense cloud of smoke and dust. Arms, heads, blankets, guns and knapsacks were thrown and tossed into the clear air. ... A moan went up from the field, distinctly to be heard amid the storm of battle.

Lt. Col. Franklin Sawyer, 8th Ohio[30]

Trimble's division of two brigades followed Pettigrew's, but made poor progress. Confusing orders from Trimble caused Lane to send only three and a half of his North Carolina regiments forward. Renewed fire from the 8th Ohio and the onslaught of Hays' riflemen prevented most of these men from getting past the Emmitsburg Road. Scales's North Carolina brigade, led by Col. William L. J. Lowrance, started with a heavier disadvantage—they had lost almost two-thirds of their men on July 1. They were also driven back and Lowrance was wounded. The Union defenders also took casualties, but Hays encouraged his men by riding back and forth just behind the battle line, shouting "Hurrah! Boys, we're giving them hell!". Two horses were shot out from under him. Historian Stephen W. Sears calls Hays' performance "inspiring".[31]

On the right flank, Pickett's Virginians crossed the Emmitsburg road and wheeled partially to their left to face northeast. They marched in two lines, led by the brigades of Brig. Gen. James L. Kemper on the right and Brig. Gen. Richard B. Garnett on the left; Brig. Gen. Lewis A. Armistead's brigade followed closely behind. As the division wheeled to the left, its right flank was exposed to McGilvery's guns and the front of Doubleday's Union division on Cemetery Ridge. Stannard's Vermont Brigade marched forward, faced north, and delivered withering fire into the rear of Kemper's brigade. At about this time, Hancock, who had been prominent in displaying himself on horseback to his men during the Confederate artillery bombardment, was wounded by a bullet striking the pommel of his saddle, entering his inner right thigh along with wood fragments and a large bent nail. He refused evacuation to the rear until the battle was settled.[32]

As Pickett's men advanced, they withstood the defensive fire of first Stannard's brigade, then Harrow's, and then Hall's, before approaching a minor salient in the Union center, a low stone wall taking an 80-yard right-angle turn known afterward as "The Angle". It was defended by Brig. Gen. Alexander S. Webb's Philadelphia Brigade. Webb placed the two remaining guns of (the severely wounded) Lt. Alonzo Cushing's Battery A, 4th U.S. Artillery, at the front of his line at the stone fence, with the 69th and 71st Pennsylvania regiments of his brigade to defend the fence and the guns. The two guns and 940 men could not match the massive firepower that Hays' division, to their right, had been able to unleash.[33]

Two gaps opened up in the Union line: the commander of the 71st Pennsylvania ordered his men to retreat when the Confederates came too close to the Angle; south of the copse of trees, the men of the 59th New York (Hall's brigade) inexplicably bolted for the rear. In the latter case, this left Captain Andrew Cowan and his 1st New York Independent Artillery Battery to face the oncoming infantry. Assisted personally by artillery chief Henry Hunt, Cowan ordered five guns to fire double canister simultaneously. The entire Confederate line to his front disappeared. The gap vacated by most of the 71st Pennsylvania, however, was more serious, leaving only a handful of the 71st, 268 men of the 69th Pennsylvania, and Cushing's two 3-inch rifled guns to receive the 2,500 to 3,000 men of Garnett's and Armistead's brigades as they began to cross the stone fence. The Irishmen of the 69th Pennsylvania resisted fiercely in a melee of rifle fire, bayonets, and fists. Webb, mortified that the 71st had retreated, brought the 72nd Pennsylvania (a Zouave regiment) forward. Initially, the regiment was hesitant to attack, this being due to the regiment not recognizing Webb as brigadier general (he had recently been promoted.) However, the 72nd moved forward after realizing their error, helping to plug the gap in the line. During the fight, Lt. Cushing was killed as he shouted to his men, three bullets striking him, the third in his mouth. The Confederates seized his two guns and turned them to face the Union troops (to no avail, as the armaments lacked ammunition). At this point, Union soldiers arrived and successfully charged into the breach.

The advancing Northerners overwhelmed the Confederate forces; the rebel advance then collapsed in turn. Given that Union forces had killed each senior Confederate officer commanding the forward-most units, no man had the authority to command the Southern forces to fall back in an orderly manner. This resulted in a disorganized retreat. [34]

The infantry assault lasted less than an hour. The supporting attack by Wilcox and Lang on Pickett's right was never a factor; they did not approach the Union line until after Pickett was defeated, and their advance was quickly broken up by McGilvery's guns and by the Vermont Brigade.[35]

Aftermath

While the Union lost about 1,500 killed and wounded, the Confederate casualty rate was over 50%. Pickett's division suffered 2,655 casualties (498 killed, 643 wounded, 833 wounded and captured, and 681 captured, unwounded). Pettigrew's losses are estimated to be about 2,700 (470 killed, 1,893 wounded, 337 captured). Trimble's two brigades lost 885 (155 killed, 650 wounded, and 80 captured). Wilcox's brigade reported losses of 200, Lang's about 400. Thus, total losses during the attack were 6,555, of which at least 1,123 Confederates were killed on the battlefield, 4,019 were wounded, and a good number of the injured were also captured. Confederate prisoner totals are difficult to estimate from their reports; Union reports indicated that 3,750 men were captured.[36]

The casualties were also high among the commanders of the charge. Trimble and Pettigrew were the most senior casualties of the day; Trimble lost a leg, and Pettigrew received a minor wound to the hand (only to die from a bullet to the abdomen suffered in a minor skirmish during the retreat to Virginia).[37] In Pickett's division, 26 of the 40 field grade officers (majors, lieutenant colonels, and colonels) were casualties—twelve killed or mortally wounded, nine wounded, four wounded and captured, and one captured.[38] All of his brigade commanders fell: Kemper was wounded seriously, captured by Union soldiers, rescued, and then captured again during the retreat to Virginia; Garnett and Armistead were killed. Garnett had a previous leg injury and rode his horse during the charge, despite knowing that conspicuously riding a horse into heavy enemy fire would mean almost certain death.

Armistead, known for leading his brigade with his cap on the tip of his sword, made the farthest progress through the Union lines. He was mortally wounded, falling near "The Angle" at what is now called the high-water mark of the Confederacy and died two days later in a Union hospital. Ironically, the Union troops that fatally wounded Armistead were under the command of his old friend, Winfield Scott Hancock, who was himself severely wounded in the battle. Per his dying wishes, Longstreet delivered Armistead's Bible and other personal effects to Hancock's wife, Almira.[39] Of the 15 regimental commanders in Pickett's division, the Virginia Military Institute produced 11 and all were casualties—six killed, five wounded.[40]

Stuart's cavalry action in indirect support of the infantry assault was unsuccessful. He was met and stopped by Union cavalry under the command of Brig. Gen. David McMurtrie Gregg about three miles (5 km) to the east, in East Cavalry Field.[41]

As soldiers straggled back to the Confederate lines along Seminary Ridge, Lee feared a Union counteroffensive and tried to rally his center, telling returning soldiers and Wilcox that the failure was "all my fault". Pickett was inconsolable for the rest of the day and never forgave Lee for ordering the charge. When Lee told Pickett to rally his division for the defense, Pickett allegedly replied, "General, I have no division."[42]

The Union counteroffensive never came; the Army of the Potomac was exhausted and nearly as damaged at the end of the three days as the Army of Northern Virginia. Meade was content to hold the field. On July 4, the armies observed an informal truce and collected their dead and wounded. Meanwhile, Maj. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant accepted the surrender of the Vicksburg garrison along the Mississippi River, splitting the Confederacy in two. These two Union victories are generally considered the turning point of the American Civil War.[43]

History may never know the true story of Lee's intentions at Gettysburg. He never published memoirs, and his after-action report from the battle was cursory. Most of the senior commanders of the charge were casualties and did not write reports. Pickett's report was apparently so bitter that Lee ordered him to destroy it, and no copy has been found.[44] Years later, when asked why the charge at Gettysburg failed, Pickett reportedly said, "I've always thought the Yankees had something to do with it."[45][46]

Virginian newspapers praised Pickett's Virginia division as making the most progress during the charge, and the papers used Pickett's comparative success as a means of criticizing the actions of the other states' troops during the charge. It was this publicity that played a significant factor in selecting the name Pickett's Charge. Pickett's military career was never the same after the charge, and he was displeased about having his name attached to the repulsed charge. In particular North Carolinians have long taken exception to the characterizations and point to the poor performance of Brockenbrough's Virginians in the advance as a major causative factor of failure.[47] Some historians have questioned the primacy of Pickett's role in the battle. W. R. Bond wrote in 1888, "No body of troops during the last war made as much reputation on so little fighting."[48]

Additional controversy developed after the battle about Pickett's personal location during the charge. The fact that fifteen of his officers and all three of his brigadier generals were casualties while Pickett managed to escape unharmed led many to question his proximity to the fighting and, by implication, his personal courage. The 1993 film Gettysburg depicts him observing on horseback from the Codori Farm at the Emmitsburg Road, but there is no historical evidence to confirm this. It was established doctrine in the Civil War that commanders of divisions and above would "lead from the rear", while brigade and more junior officers were expected to lead from the front, and while this was often violated, there was nothing for Pickett to be ashamed of if he coordinated his forces from behind.[49]

The Lost Cause

Pickett's Charge has become one of the central symbols of the literary and cultural movement known as the Lost Cause, in particular for Virginians.[50] Proponents extol the bravery of Confederate soldiers attacking headlong into Union lines, the capable leadership of southern generals inspiring overwhelming confidence in their men, especially that of Virginians such as Lee and Pickett, and the tantalizing closeness of ultimate victory. William Faulkner, the quintessential Southern novelist, summed up the picture in Southern myth of this gallant but futile episode:[51]

For every Southern boy fourteen years old, not once but whenever he wants it, there is the instant when it's still not yet two o'clock on that July afternoon in 1863, the brigades are in position behind the rail fence, the guns are laid and ready in the woods and the furled flags are already loosened to break out and Pickett himself with his long oiled ringlets and his hat in one hand probably and his sword in the other looking up the hill waiting for Longstreet to give the word and it's all in the balance, it hasn't happened yet, it hasn't even begun yet, it not only hasn't begun yet but there is still time for it not to begin against that position and those circumstances which made more men than Garnett and Kemper and Armistead and Wilcox look grave yet it's going to begin, we all know that, we have come too far with too much at stake and that moment doesn't need even a fourteen-year-old boy to think This time. Maybe this time with all this much to lose than all this much to gain: Pennsylvania, Maryland, the world, the golden dome of Washington itself to crown with desperate and unbelievable victory the desperate gamble, the cast made two years ago.

— William Faulkner, Intruder in the Dust

Over time this view came to dominate perceptions of the battle, despite the initial protestations from groups both north and south.[52] Northern veterans in particular opposed the decreasing emphasis on their hard-fought defense of Cemetery Ridge in favor of extolling the bravery and sacrifice of the attacking Confederate army.[53] Non-Virginian southerners took offense at the overwhelming focus the myth places on Virginian leaders and Virginian troops, despite that larger number of Northern Carolina troops, who sustained greater casualties than the Virginian regiments.[54] Nevertheless, after decades of strident historicizing this narrative had firmly taken root and by the battle's 50th anniversary in 1913 it had become in many ways the standard interpretation of what occurred.[55]

Modern analysis, however, has increasingly shifted away from many of the Lost Cause interpretation's tenets.[56] Lee's decision to conduct the attack has been characterized as the culmination of multiple strategic and tactical blunders,[57] and the sacrifice of his troops as unnecessary.[58] Examination of casualty records, capture reports, and first hand accounts has revealed that substantial numbers of Confederate troops involved in the attack refused to make the final charge, instead choosing to shelter in the sunken depression of the Emmitsburg Road and surrender to Union soldiers after the battle.[59] And later research has shown that it is unlikely Pickett's charge could ever have provided the decisive victory imagined by Lee; a study using the Lanchester model to examine several alternative scenarios suggested that Lee could have captured a foothold on Cemetery Ridge if he had committed several more infantry brigades to the charge; but this likely would have left him with insufficient reserves to hold or exploit the position afterwards.[60]

The battlefield today

The site of Pickett's Charge is one of the best-maintained portions of the Gettysburg Battlefield. Despite millions of annual visitors to Gettysburg National Military Park, very few have walked in the footsteps of Pickett's division. The National Park Service maintains a neat, mowed path alongside a fence that leads from the Virginia Monument on West Confederate Avenue (Seminary Ridge) due east to the Emmitsburg Road in the direction of the Copse of Trees.

Pickett's division, however, started considerably south of that point, near the Spangler farm, and wheeled to the north after crossing the road. In fact, the Park Service pathway stands between the two main thrusts of Longstreet's assault—Trimble's division advanced north of the current path, while Pickett's division moved from farther south.[61]

A cyclorama painting by the French artist Paul Philippoteaux entitled The Battle of Gettysburg, also known as the Gettysburg Cyclorama, depicts Pickett's Charge from the vantage point of the Union defenders on Cemetery Ridge. Completed and first exhibited in 1883, it is one of the last surviving cycloramas in the United States. It was restored and relocated to the new National Park Service Visitor Center in September 2008.[62]

Notes

- Pfanz, pp. 44–52.

- War of the Rebellion: Official Records (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1889), Volume 27, Series I, Part 2, p. 320.

- A. L. Long. Memoirs of Robert E. Lee: His Military and Personal History. London: Sampson, Low, Marston, Seale and Rivington, 1886, pp. 287–288.

- Eicher, pp. 544–546.

- Sears, p. 345.

- Harman, pp. 63–83.

- Coddington, pp. 461, 489.

- Eicher, p. 544. Examples of "Pickett–Pettigrew–Trimble" citations are Sears, p. 359, Hall, p. 185, Gottfried, Map Set 26, and Encyclopedia Virginia, s.v. "Numbers at Pickett's Charge", accessed May 3, 2011. Dixon, p. 79, refers to the "Picket–Pettigrew Assault".

- Sears, p. 391.

- Wert, pp. 98–99.

- Gallagher, p. 141.

- Coddington, pp. 454–455.

- Sears, pp. 377–80; Wert, p. 127; Coddington, p. 485.

- Symonds, p. 214: "It may well have been the loudest man-made sound on the North American continent until the detonation of the first atomic bomb at Alamogordo, New Mexico.

- Coddington, p. 502, indicates the bombardment stopped at 3 p.m. Hess, p. 162, writes that the bombardment was essentially over by 2 p.m. Wert, p. 182, states that accounts from participants of the bombardment duration vary from 45 minutes to two hours or more, but the "most reliable" are one hour, because the Confederates did not have sufficient ammunition to fire longer than that. Sears, p. 415, states the bombardment ended at 2:30 p.m.

- Estimates of the guns deployed vary. Coddington, p. 493: "over 150"; Eicher, p. 543: 159; Trudeau, p. 452: 164; Symonds, p. 215: "more than 160"; Clark, p. 128, "about 170"; Pfanz, p. 45: "170 (we cannot know the exact number)." All agree that approximately 80 guns available in the Army of Northern Virginia were not used during the bombardment.

- Eicher, p. 543.

- Sears, pp. 397–400; Wert, pp. 175, 184; Coddington, p. 497; Hess, pp. 180–81; Clark, p. 135.

- Sears, p. 383. The temperature was recorded at 2 p.m. by Professor Michael Jacobs of Gettysburg College.

- Hess, p. 151.

- Wert, p. 283.

- Longstreet, p. 392; Coddington, pp. 500–502; Hess pp. 160–61.

- Hess, pp. 161–62.

- Estimates vary substantially. Clark, p. 131: 12,000; Sauers, p. 835: 10,500 to 15,000; Eicher, p. 544: 10,500 to 13,000; Sears, p. 392: "13,000 or so"; Pfanz, p. 44: "about 12,000"; Coddington, p. 462: 13,500; Hess, p. 335: 11,830.

- Rable, George (2002). Fredericksburg! Fredericksburg!. University of North Carolina Press. p. 1-2. ISBN 0-8078-2673-1.

- Priest, John M. "Pickett's Charge". Essential Civil War Curriculum.

Union and Confederate accounts clearly state that most of the captured were found in the Emmitsburg Road and in the killing zone between the Road and the Federal line. The fact that captured men outnumbered the killed and wounded indicates that many did not leave the cover of the roadbed.

- Hess, p. 171; Clark, p. 137; Sears, pp. 424–26.

- Priest, John M. "Pickett's Charge". Essential Civil War Curriculum.

Recall that the attack front shrank from over 5,280 feet to 2,200 feet, meaning that about 68% for whatever reason did not get close to the Federal line. Armistead's frontage, in the second line, shrank from about 2,100 feet to around 750 feet by the time his brigade reached the Emmitsburg Road, a reduction of 64%.

- Sears, pp. 422–25, 429–31; Hess, pp. 188–90.

- Sears, p. 422.

- Sears, pp. 434–35.

- Clark, pp. 139–43; Pfanz, p.51; Sears, pp. 436–39.

- Sears, pp. 436–43;.

- Sears, pp. 444–54, "the 59th suddenly and unaccountably bolted"; Trudeau, p. 506; Hess, pp. 245, 271–76; Wert, pp. 212–13.

- Eicher, pp. 547–48; Sears, pp. 451–54.

- Hess, pp. 333–35; Sears, p. 467.

- Sears, p. 467; Eicher, pp. 548–49.

- Wert, pp. 291–92.

- Armistead Hancock story Archived 2011-07-11 at the Wayback Machine, Brigade Ministry: Examples of personal ministry among the troops, accessed January 5, 2009.

- Hess, p. 335.

- Pfanz, pp. 52–53.

- Hess, p. 326; Sears, p. 458; Wert, pp. 251–52, disputes prevalent accounts that Lee and Pickett met personally after the battle.

- Pfanz, p. 53.

- Wert, p. 297.

- Boritt, p. 19.

- Savas, Theodore P.; Woodbury, David A. (2013). The Campaign for Atlanta & Sherman's March to the Sea, Volume 1. Savas Publishing. ISBN 9781940669052. Retrieved July 11, 2017.

- Desjardins, p. 47; Sears, p. 359.

- Bond, W.R. Pickett or Pettigrew? An Historical Essay. Scotland Neck: W.W. Hall, 1888.

- Sears, pp. 426, 455; Coddington, pp. 504–505.

- Reardon, Carol (1997). Pickett's Charge in History and Memory. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press.

- Quoted in Desjardins, pp. 124–25.

- Reardon, pp. 108-130 for northern objections, and pp. 131-153 for southern ones.

- Reardon, pp. 108

- Reardon pp. 131

- Reardon, pp. 154-175

- "Pickett's Charge". Encyclopedia Virginia.

Just as late in the twentieth century the Lost Cause lost most of its academic support, so did historians begin to challenge the traditional narrative of Pickett's Charge. Pickett's Charge in History and Memory (1997) by Carol Reardon and Pickett's Charge—The Last Attack at Gettysburg (2001) by Earl J. Hess attempted to untangle history and memory. They argued that the struggle to shape the memory of Pickett's Charge obscured its history, devalued the role of non-Virginians, and exaggerated the attack's importance in the context of the war.

- Davis, William C. (2016). Crucible of Command: Ulysses S. Grant and Robert E. Lee -- The War They Fought, the Peace They Forged. Da Capo Press.

[Lee] forfeited any long- or midrange tactical reconnaissance Stuart might have provided, and as a result had no grasp of the overall battlescape. He learned of Union movements too late to react, and never identified Meade's center of gravity in order to direct his own efforts to best effect. He let Hill bring on a major engagement despite instructions not to do so, and then gave orders too imprecise and discretionary to be effective. Five years later Lee offered two reasons for defeat: Stuart's absence left him blind; and he could not deliver the "one determined and united blow" that he believed would have assured victory. . . . What he did not say was that he was ultimately responsible. He let Stuart go, and his own laissez-faire management helped bungle the attacks on July 1 and 2. . . . Every general has his worst battle. Gettysburg was Lee's.

- Gompert, David C.; Kugler, Richard L. (August 2006). "Lee's Mistake: Learning from the Decision to Order Pickett's Charge" (PDF). Defense Horizons. 54.

- Priest, John M. "Pickett's Charge". Essential Civil War Curriculum.

- Armstrong MJ, Sodergren SE. 2015, Refighting Pickett’s Charge: mathematical modeling of the Civil War battlefield, Social Science Quarterly 96:4, 1153-1168.

- Harman, pp. 77, 116; Sears, map, p. 427.

- Heiser, John (2005). "The Gettysburg Cyclorama". Gettysburg National Military Park. National Park Service. Retrieved February 21, 2008.

References

- Boritt, Gabor S., ed. Why the Confederacy Lost. Gettysburg Civil War Institute Books. New York: Oxford University Press, 1992. ISBN 0-19-507405-X.

- Clark, Champ, and the Editors of Time-Life Books. Gettysburg: The Confederate High Tide. Alexandria, VA: Time-Life Books, 1985. ISBN 0-8094-4758-4.

- Coddington, Edwin B. The Gettysburg Campaign; a study in command. New York: Scribner's, 1968. ISBN 0-684-84569-5.

- Desjardin, Thomas A. These Honored Dead: How the Story of Gettysburg Shaped American Memory. New York: Da Capo Press, 2003. ISBN 0-306-81267-3.

- Dixon, Benjamin Y. Learning the Battle of Gettysburg: A Guide to the Official Records. Gettysburg, PA: Thomas Publications, 2007. ISBN 978-1-57747-121-9.

- Eicher, David J. The Longest Night: A Military History of the Civil War. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2001. ISBN 0-684-84944-5.

- Gallagher, Gary W. Lee and His Generals in War and Memory. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1998. ISBN 0-8071-2958-5.

- Gottfried, Bradley M. The Maps of Gettysburg: An Atlas of the Gettysburg Campaign, June 3–13, 1863. New York: Savas Beatie, 2007. ISBN 978-1-932714-30-2.

- Hall, Jeffrey C. The Stand of the U.S. Army at Gettysburg. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2003. ISBN 0-253-34258-9.

- Harman, Troy D. Lee's Real Plan at Gettysburg. Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books, 2003. ISBN 0-8117-0054-2.

- Hess, Earl J. Pickett's Charge – The Last Attack at Gettysburg. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2001. ISBN 0-8078-2648-0.

- Longstreet, James. From Manassas to Appomattox: Memoirs of the Civil War in America. New York: Da Capo Press, 1992. ISBN 0-306-80464-6. First published in 1896 by J. B. Lippincott and Co.

- Pfanz, Harry W. The Battle of Gettysburg. Conshohocken: Eastern National Park and Monument Association, 1994.

- Sears, Stephen W. Gettysburg. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 2003. ISBN 0-395-86761-4.

- Stewart, George R. (1959). Pickett's Charge: A Microhistory of the Final Attack at Gettysburg, July 3, 1863. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. LCCN 59-8864..

- Symonds, Craig L. American Heritage History of the Battle of Gettysburg. New York: HarperCollins, 2001. ISBN 0-06-019474-X.

- Trudeau, Noah Andre. Gettysburg: A Testing of Courage. New York: HarperCollins, 2002. ISBN 0-06-019363-8.

- Wert, Jeffry D. Gettysburg: Day Three. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2001. ISBN 0-684-85914-9.

Further reading

| External video | |

|---|---|

- Bearss, Edwin C. Fields of Honor: Pivotal Battles of the Civil War. Washington, DC: National Geographic Society, 2006. ISBN 0-7922-7568-3.

- Bearss, Edwin C. Receding Tide: Vicksburg and Gettysburg: The Campaigns That Changed the Civil War. Washington, DC: National Geographic Society, 2010. ISBN 978-1-4262-0510-1.

- Gallagher, Gary W., ed. The Third Day at Gettysburg and Beyond. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1998. ISBN 0-8078-4753-4.

- Haskell, Frank Aretas. The Battle of Gettysburg. Whitefish, MT: Kessinger Publishing, 2006. ISBN 978-1-4286-6012-0.

- Laino, Philip, Gettysburg Campaign Atlas. 2nd ed. Dayton, OH: Gatehouse Press 2009. ISBN 978-1-934900-45-1.

- McCulloch, Captain Robert. The High Tide at Gettysburg. 1915.

- Petruzzi, J. David, and Steven Stanley. The Complete Gettysburg Guide. New York: Savas Beatie, 2009. ISBN 978-1-932714-63-0.

- Reardon, Carol. Pickett's Charge in History and Memory. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2009. ISBN 978-0-8078-5461-7.