Pierre Barrois

Pierre Barrois (30 October 1774 – 19 October 1860) became a French division commander during the Napoleonic Wars. He joined a volunteer battalion in 1793 that later became part of a famous light infantry regiment. He fought at Wattignies, Fleurus, Aldenhoven, Ehrenbreitstein and Neuwied in 1793–1797. He fought at Marengo in 1800. He became colonel of a line infantry regiment in 1803 and led it at Haslach, Dürrenstein, Halle, Lübeck and Mohrungen in 1805–1807. Promoted to general of brigade, he led a brigade at Friedland in 1807.

Pierre Barrois | |

|---|---|

Pierre Barrois | |

| Born | 30 October 1774 Ligny-en-Barrois, France |

| Died | 19 October 1860 (aged 85) Villiers-sur-Orge, Seine-et-Oise, France |

| Allegiance | |

| Service/ | Infantry |

| Years of service | |

| Rank | General of Division |

| Battles/wars |

|

| Awards | Légion d'Honneur, GC 1836 |

| Other work | Count of the Empire |

Transferring to Spain, Barrois led his brigade at Espinosa, Somosierra, Uclés, Medellín, Talavera, Cádiz and Barrosa in 1808–1811. He was promoted to general of division in 1811 and led a Young Guard division at Bautzen, Dresden, Leipzig and Courtrai in 1813–1814. The following year he led Imperial Guard troops at Ligny and Waterloo. After a period of retirement, he led French troops that intervened in the Belgian Revolution. His surname is one of the names inscribed under the Arc de Triomphe, on Column 37.

Early career

Barrois was born on 30 October 1774 at Ligny-en-Barrois in what later became the Meuse department. His father was a baker. On 12 August 1793, Barrois enlisted in the Éclaireurs (Scouts) of the Meuse and became a lieutenant exactly one month later. He fought at the Battle of Wattignies on 12–13 October 1793.[1] His unit belonged to the division of Pierre Raphaël Paillot de Beauregard.[2] This division was described by one historian as, "bad troops under a bad general", and performed poorly in the action.[3] In 1794, the Éclaireurs of the Meuse were amalgamated with the Chasseurs of Cévennes to become part of the 9th Light Infantry Regiment.[4]

Barrois fought at the Battle of Fleurus on 26 June 1794 in the division of François Séverin Marceau-Desgraviers.[5] The 9th Light Infantry Regiment was listed in a 9 June order of battle for Marceau's division.[6] The next action fought by this division was the Battle of Lambusart on 16 June.[7] The flight of "the shaky troops of the Ardennes" Army under Marceau caused the French to retreat on 16 June.[8] Again at Fleurus, Marceau's troops took to their heels. However, this time Marceau was able to rally some soldiers and bring them back into action.[9] After very hard fighting, the Allies gave up and retreated from the field.[10]

Marceau's division fought at the Battle of Sprimont on 17–18 September 1794. The French feinted with their left wing, but the real thrust was made by the right wing divisions of Marceau, Jean Adam Mayer and Honoré Alexandre Haquin, plus part of Jacques Maurice Hatry's. The right wing counted almost 60,000 men under the overall command of Barthélemy Louis Joseph Schérer. An Allied observer, Louis Alexandre Andrault de Langeron witnessed the French assault on the bridge of Aywaille, "on which the Austrians had placed two 12-pounder guns, which fired case shot on the attackers. They passed it, throwing into the river their dead and wounded who obstructed their passage. With their generals in front, they descended the scarped bank of the Ourthe torrent and crossed it..." This heroic attack was made by the same soldiers who ran away at Lambusart and Fleurus.[11] Barrois fought at the Battle of the Roer (Aldenhoven) on 2 October.[4] In this action, Marceau and Mayer captured Düren but Haquin's division was sent on a flank march and did not arrive until nightfall. Nevertheless, the Austrians withdrew that night.[12]

During the Second Siege of Mainz Barrois was promoted to captain adjutant-major.[4] Actually, Marceau's division and the 9th Light Infantry were engaged at the siege of Ehrenbreitstein Fortress from 15 September to 17 October 1795.[13] Barrois fought at the Battle of Neuwied[5] on 18 April 1797.[14] He was transferred to Brest in order to take part in the 1798 expedition to Ireland. Later he was assigned to the Vendée. The 9th Light was assigned to the Army of Reserve and fought at the Battle of Marengo on 14 June 1800[5] as part of Jean Boudet's division.[15] It performed so well that Napoleon had the word incomparable embroidered on the regimental flag.[4] In October 1800, Barrois was appointed chef de bataillon.[5]

Empire

Regimental commander

On 5 October 1803, Barrois received promotion to colonel commanding the 96th Line Infantry Regiment.[16] His unit was stationed at Mont Cenis in the Alps under the orders of Michel Ney and he became a Chevalier of the Legion of Honor.[4] The 96th Line was assigned to the brigade of Jean Gabriel Marchand in the division of Pierre Dupont de l'Étang. Barrois sat on the military commission that condemned Louis Antoine, Duke of Enghien to death. When the War of the Third Coalition broke out, he won distinction at the Battle of Haslach-Jungingen[5] on 11 October 1805. In this action, Dupont's 5,350 infantry, 2,169 cavalry and 18 guns fought 25,000 Austrians to a standstill.[17] Dupont's division also fought at the Battle of Dürrenstein on 11 November.[18] After this campaign, Barrois was made a Commander of the Legion of Honor.[4]

During the War of the Fourth Coalition in 1806, Barrois led his regiment at the battles of Halle, Nossentin and Lübeck. In 1807, he fought at the Battle of Mohrungen.[5] On 14 February 1807 he was promoted to general of brigade.[16] Given a brigade in Dupont's division, Barrois led his troops in a skirmish at Braniewo (Braunsberg) and at the Battle of Friedland on 14 June 1807.[5] At Friedland, Dupont's division greatly distinguished itself, piercing the Russian center and repelling attacks by the Russian Imperial Guard.[19] In recognition, Napoleon appointed Barrois a Grand Officer of the Legion of Honor.[4]

Spain

In 1808, the I Corps under Marshal Claude Perrin Victor was transferred to Spain to fight in the Peninsular War. Barrois commanded the 2nd Brigade in Dupont's former division, now led by François Amable Ruffin. He led his brigade with distinction at the Battle of Espinosa de los Monteros[5] on November 10–11, 1808. In this action, Victor recklessly attacked on the first day before all his troops were available and was repulsed. On the second day, the marshal made a more skillful assault and routed the Spanish army. The French lost 1,000 killed and wounded while inflicting 3,000 casualties and capturing six guns and the Spanish wagon train.[20]

In the Battle of Somosierra on 30 November 1808, Ruffin's division led the advance of the French army up the Somosierra Pass. While the 9th Light Infantry advanced to the right and the 24th Line to the left, Barrois led the 96th Line directly up the main road. An impatient Napoleon ordered a premature charge of Polish cavalry which was nearly wiped out. Not long afterward, the flanking regiments cleared the heights on either side and Barrois' men nearly reached the crest. Napoleon ordered another cavalry charge and this time the Spanish defenders were routed.[21] At the Battle of Uclés on 13 January 1809, Victor ordered Eugène-Casimir Villatte's division to attack the Spanish defenders while Ruffin circled around to get behind them. The operation worked perfectly. Villatte drove the Spanish out of their positions without much trouble. As they retreated, the Spanish infantry ran into Ruffin's division and 6,000 men were forced to surrender in a body. Although they had sustained few casualties, the French committed atrocities by murdering 69 townspeople and a number of prisoners.[22]

Ruffin's division was in reserve at the Battle of Medellín on 29 March 1809.[23] Late on 27 July at the Battle of Talavera, Victor ordered Ruffin's division to make a night attack on the British position. Only the 9th Light succeeded in reaching the crest of the hill, only to be driven off. The 24th and 96th Line got lost in the dark.[24] Early in the morning of 28 July, Ruffin's division attacked again and was badly mauled, losing 1,300 men.[25] In the afternoon, Ruffin's division advanced on the extreme right flank and was attacked by cavalry. The 1st Light Dragoons of the King's German Legion became disordered after riding into a hidden gully, then attacked the 24th Line which was formed in square. The Germans were easily driven off.[26] Barrois was appointed Baron of the Empire on 24 February 1809.[16]

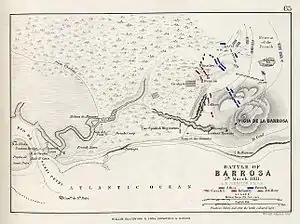

Barrois served at the Siege of Cádiz in 1810. He fought at the Battle of Barrosa on 5 March 1811 and took command of the division after Ruffin was fatally wounded and captured.[5] He was promoted general of division on 27 July 1811.[16] On 28 October 1811, a British force under Rowland Hill surprised and mauled one of Jean-Baptiste Girard's brigades at the Battle of Arroyo dos Molinos. For this minor disaster, Girard was disgraced and replaced in command of the division by Barrois. The division consisted of the 34th, 40th, 64th and 88th Line Infantry Regiments, of which the first two were involved in the debacle.[27] Barrois' division took part in the Siege of Tarifa in December 1811. During the approach march, Francisco Ballesteros and 2,000 Spaniards attacked the French, but Barrois drove them off.[28]

In a 3 March 1812 report, Barrois commanded the 2nd Division of the Army of the South, with 225 officers and 7,551 rank and file. The 1st Brigade was led by Louis Victorin Cassagne and included the 16th Light and 8th Line Infantry Regiments. The 2nd Brigade was directed by Jean-Jacques Avril and consisted of the 51st and 54th Line Infantry Regiments. All regiments had three battalions and the divisional headquarters was at Puerto Real near Cádiz.[29] In July 1812, Barrois' division was sent to reinforce Jean-Baptiste Drouet, comte d'Erlon, who was threatened by Hill's corps.[30] There was a back-and-forth campaign with no battle in which the division participated.[31] Told to report to Vilnius, he arrived after the end of the French invasion of Russia.[4]

1813–1814

At the Battle of Bautzen on 20–21 May 1813, Barrois commanded the 2nd Young Guard Division which had two brigades. The 1st Brigade under Henri Rottembourg consisted of the 1st and 2nd Tirailleur Regiments while the 2nd Brigade of Pierre Berthezène was made up of the 3rd, 6th and 7th Tirailleurs. Each regiment had two battalions and the three regiments that had strength returns counted 946, 1,058 and 1,074 officers and men.[32] At 3:00 pm on the second day, Barrois' division advanced to attack the Allied position, supported by heavy artillery fire. Though temporarily halted by Russian cannons, the Allies were compelled to retreat around 4:00 pm.[33] At the Battle of Dresden on 26–27 August, Barrois' 2nd Division formed part of Marshal Édouard Mortier's command.[34] On 26 October, Mortier's troops recaptured the Great Garden from the Allies. The next day, the Imperial Guard drove back the Allied right flank.[35]

At the Battle of Leipzig on 16–19 October, Barrois' 2nd Division was part of Mortier's II Young Guard Corps. The 1st Brigade led by Paul-Jean-Baptiste Poret de Morvan included the 1st, 2nd and 3rd Tirailleurs while the 2nd Brigade of Louis-Étienne Dulong de Rosnay comprised the 6th and 7th Tirailleurs. Each regiment had two battalions and the division numbered 5,470 men.[36] Attached artillery consisted of the 3rd, 4th and 12th Young Guard Foot Artillery Companies and the 3rd and 9th Companies of the 1st Guard Train Regiment. Each of the three artillery batteries had six 6-pounder System Year XI cannons and two 5 ½-inch howitzers.[37] At 2:00 pm on 16 October, Mortier's corps advanced to attack the University Wood, but Napoleon was unable to secure a decisive victory.[38] The divisions of Barrois and François Roguet acted as the French army's rearguard. By the time they reached the Rhine River, Barrois' division was reduced to 2,500 men.[4]

On 11 January 1814, Nicolas Joseph Maison ordered Barrois to force march his division from Brussels to Antwerp.[39] In early January, Barrois' 4th Young Guard Division consisted of the 1st, 2nd, 3rd and 4th Tirailleur Regiments which numbered 103 officers and 4,096 men.[40] Brussels was evacuated on 1 February and Barrois' division retreated from there to Tournai.[41] On 21 February 1814 Barrois was appointed Count of the Empire.[16] By 5 March, Maison's field force included 5,400 men in the infantry divisions of Barrois and Jean-Baptiste Solignac plus 930 cavalry and 19 guns.[42]

On 25 March 1814, Maison's command left Lille and headed north. At this time Barrois' division numbered 2,971 men and included the 12th Voltiguer and 2nd, 3rd and 4th Tirailleur Regiments. Maison was successful in reaching Antwerp where he added Roguet's 4,000 men of the 6th Young Guard Division to his force. Then the French moved south again and headed toward Lille. In the Battle of Courtrai on 31 March Maison's force was intercepted by Johann von Thielmann's Saxons. Believing that he was only facing Solignac's division, Thielmann ordered an attack. Maison placed Roguet's division in the center with Barrois on the right and Solignac on the left. Bertrand Pierre Castex's cavalry waited in reserve. When the Saxon force was fully committed, Maison ordered Barrois and Solignac to envelop the flanks. Barrois' attack was led by Jean-Luc Darriule's brigade. Too late, Thielmann realized he was facing Maison's entire corps and called for a withdrawal. His command disintegrated as the Saxons took to their heels and the French rounded up hundreds of prisoners. A week later, Maison learned that Napoleon had abdicated and the war was over.[43]

Later career

During the Hundred Days, Barrois rallied to Napoleon and was given command of the 1st Young Guard Division[5] and led it in the Waterloo Campaign. The division consisted of the 1st and 3rd Tirailleurs and the 1st and 3rd Voltigeurs.[44] Barrois led the Tirailleurs at the Battle of Ligny. At the Battle of Waterloo on 18 June 1815 he was shot in the left shoulder while directing the defense of Plancenoit. He immediately went on leave to have his injury tended.[5] He was placed on retired status on 1 January 1825. Barrois returned to active duty in 1830 to command the 3rd Division and serve as inspector general of infantry. In August 1831 he was part of the French army that intervened in the Belgian Revolution. In 1836 he was awarded the Grand Cross of the Legion of Honor. Barrois is inscribed on the west pillar of the Arc de Triomphe.[4] He is buried in the 27th division of the Père Lachaise Cemetery in Paris.[45]

Notes

- Mullié 1852, p. 39.

- Dupuis 1909, p. 102.

- Phipps 2011a, p. 256.

- Mullié 1852, p. 40.

- Jensen 2015.

- Smith 1998, p. 71.

- Smith 1998, p. 84.

- Phipps 2011b, p. 153.

- Phipps 2011b, p. 161.

- Phipps 2011b, pp. 163–164.

- Phipps 2011b, pp. 181–183.

- Phipps 2011b, pp. 184–185.

- Smith 1998, pp. 106–107.

- Smith 1998, p. 134.

- Smith 1998, p. 186.

- Broughton 2001.

- Smith 1998, pp. 203–204.

- Smith 1998, p. 213.

- Chandler 1966, pp. 578–579.

- Oman 2010, pp. 414–416.

- Oman 2010, pp. 456–461.

- Oman 1995, pp. 10–12.

- Oman 1995, p. 158.

- Oman 1995, pp. 516–519.

- Oman 1995, pp. 524–525.

- Oman 1995, pp. 548–549.

- Oman 1996a, pp. 602–606.

- Oman 1996b, p. 117.

- Oman 1996b, p. 590.

- Oman 1996b, p. 526.

- Oman 1996b, pp. 529–530.

- Nafziger 1992.

- Leggiere 2015, pp. 353–355.

- Smith 1998, p. 443.

- Chandler 1966, pp. 908–910.

- Smith 1998, p. 461.

- Nafziger 1990.

- Chandler 1966, p. 929.

- Leggiere 2007, p. 423.

- Nafziger 2015, p. 530.

- Nafziger 2015, p. 57.

- Nafziger 2015, p. 63.

- Nafziger 2015, pp. 363–369.

- North 1971, p. 69.

- APPL 2009.

References

- APPL (2009). "Barrois, Pierre, général comte (1774–1860)". Amis et Passionées du Père-Lachaise.

- Broughton, Tony (2001). "French Infantry Regiments and the Colonels who Led Them: 1791 to 1815: 91e - 100e Regiments: Pierre Barrois". The Napoleon Series. Retrieved 16 December 2017.

- Chandler, David G. (1966). The Campaigns of Napoleon. New York, N.Y.: Macmillan.

- Dupuis, Victor (1909). "La Campagne de 1793 a l'Armee du Nord et des Ardennes d'Hondtschoote a Wattignies" (in French). Paris: Librairie Militaire R. Chapelot et Cie. Retrieved 9 January 2018.

- Jensen, Nathan (2015). "General Pierre Barrois". frenchempire.net. Retrieved 17 December 2017.

- Leggiere, Michael V. (2007). The Fall of Napoleon: The Allied Invasion of France. Vol. 1. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-87542-4.

- Leggiere, Michael V. (2015). Napoleon and the Struggle for Germany: The War of Liberation, Spring 1813. Vol. 1. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-08051-5.

- Mullié, Charles (1852). Biographie des célébrités militaires des armées de terre et de mer de 1789 a 1850 (in French). Paris.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Nafziger, George (2015). The End of Empire: Napoleon's 1814 Campaign. Solihull, UK: Helion & Company. ISBN 978-1-909982-96-3.

- Nafziger, George (1992). Grande Armée, Battle of Bautzen, 20/21 May 1813 (PDF). Fort Leavenworth, KS: US Army Combined Arms Center.

- Nafziger, George (1990). French Army, Battle of Leipzig, 16–19 October 1813 (PDF). Fort Leavenworth, KS: US Army Combined Arms Center. Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 October 2017. Retrieved 17 December 2017.

- North, René (1971). Regiments at Waterloo. London: Almark Publishing. ISBN 978-0-85524-025-7.

- Oman, Charles (2010) [1902]. A History of the Peninsular War Volume I. Vol. 1. La Vergne, Tenn.: Kessinger Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4326-3682-1.

- Oman, Charles (1995) [1903]. A History of the Peninsular War Volume II. Vol. 2. Mechanicsburg, Pennsylvania: Stackpole. ISBN 978-1-85367-215-6.

- Oman, Charles (1996a) [1911]. A History of the Peninsular War Volume IV. Vol. 4. Mechanicsburg, Pennsylvania: Stackpole. ISBN 978-1-85367-224-8.

- Oman, Charles (1996b) [1914]. A History of the Peninsular War Volume V. Vol. 5. Mechanicsburg, Pennsylvania: Stackpole. ISBN 978-1-85367-225-5.

- Phipps, Ramsay Weston (2011a) [1926]. The Armies of the First French Republic and the Rise of the Marshals of Napoleon I: The Armée du Nord. Vol. 1. Pickle Partners Publishing. ISBN 978-1-908692-24-5.

- Phipps, Ramsay Weston (2011b) [1929]. The Armies of the First French Republic and the Rise of the Marshals of Napoleon I: The Armées du Moselle, du Rhin, de Sambre-et-Meuse, de Rhin-et-Moselle. Vol. 2. Pickle Partners Publishing. ISBN 978-1-908692-25-2.

- Smith, Digby (1998). The Napoleonic Wars Data Book. London: Greenhill. ISBN 978-1-85367-276-7.