Pijao people

The Pijao (also Piajao, Pixao, Pinao) are an indigenous people from Colombia.

Natagaima, Coyaima | |

|---|---|

Statue of a Pijao in Ibagué | |

| Total population | |

| 58,810 (2005) | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Tolima, | |

| Languages | |

| Pijao, Colombian Spanish | |

| Religion | |

| Traditional religion, Catholicism | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Panches, Quimbaya, Guayupes |

Ethnography

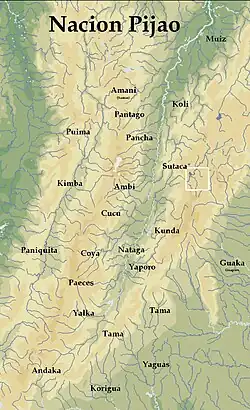

The Pijao or Pijaos formed a loose federation of Amerindians and were living in the present-day department of Tolima, Colombia. In pre-Columbian times, they inhabited the Central Ranges of the Colombian Andes; between the snowy mountains of Huila, Tolima and Quindío, the upper valley of the Magdalena River and the upper Valle del Cauca in Colombia. They did not have a strict hierarchy and did not create an empire.

The chiefdom was based on an extended family clan with ancestral lineage. The people did not live in separate households gathered in villages; instead, they lived in carefully built large communal houses made of bahareque, which were placed at distances.

They used bonfires to communicate with smoke signs, and these were used to convene different community events. Like many ancient peoples, they relied on waterways for routes of transportation; and due to their navigation skills and knowledge, could get around much of their territory fairly rapidly. They called their best navigators boha (boga). Their boats were called kanoha (canoes), and were carved from a single piece of Saman wood.

The Pijao were experts in metallurgy, manufacturing gold articles and clothing. Their work has been seen in gold artifacts from the Tolima, Quimbaya, Calima, and Cauca cultures. They used techniques such as "lost wax" casting, rolled gold, filigree and other methods to make their balacas (ornaments) and other items for ceremonial use, such as the poporos (bowl with lid).

Like some other ancient cultures, the Pijao practiced skull modification and facial alterations, as well as a variety of body modifications, perhaps to identify or distinguish elites. They tied slats on male babies' heads to alter their frontal and occipital regions, perhaps to give them a look of ferocity. They also modified the shape of their upper and lower extremities using adjusted ropes (Interlaced fiber ropes). They changed the appearance of the nose by fracturing the nasal septum. They pierced the nose and the ear lobes to wear gold ornaments and decorations symbolic of their religion. They called these body ornaments Wua-La-ka (Balak). The crowns of the elite were made of several precious materials; in addition, they wore ceremonial masks, feather crowns, bracelets, nose ornaments and other items.

They painted red their bodies for communal events with powdered achiote (Bi-Cha or Bija).[1] Their assemblies, also known as Mingas, were held under the broad shade of the Ceiba trees. The Ceiba was considered a symbol of the Great Home of a rich, generous and motherly nature. Here they carried out war ceremonies, crowning of chiefs, wedding rituals and other major events. Most were accompanied by dancing to the beat of maracas, fotuto, yaporojas and drums. Young single women (virgins) were decorated with flowers.

Agriculturalists, the Pijao lived close to the earth in homes made of wood and rammed earth. Due to the tropical climate and excellent soil in the highlands, they were able to grow, harvest and cultivate many crops including potatoes, yucca, maize, mangoes, papayas, guavas and many other fruits and vegetables. They also fished and hunted for meats.

They wore, as a custom dress, beautifully decorated golden clothes which did not cover their genitals. They painted their bodies with dyed tops of bija. The Spanish conquerors initially called them Bipxaus (Bija), the same name as one of the Paez chiefdoms. Later they referred to the people as the Pijao, which came to be considered a pejorative.

The Pijao practiced ritual cannibalism of their enemies. The Spanish captain Diego de Bocanegra (one of many military leaders who battled against the Pijao) accused them of having cannibalized up to 100,000 Spaniards in approximately 50 years.

Despite regularly driving back the invading Spaniards, the Pijao population kept decreasing and they were pushed further south in the highlands. They began to clash with neighboring tribes such as the Coconuco, Páez, Puruhá, and Cana. By the mid-18th century, the Pijao people had suffered drastic losses, mostly due to new infectious diseases. Missionary Christians had also taken a toll through conversion and re-education of many natives.

The Spanish followed their invasions with colonization of most of the central highlands and the Andes mountain ranges. Through these measures they established the New Kingdom of Granada.

Language

The Pijao language is extinct since the 1950s and has not been classified. It is not listed in Kaufman (1994).

References

-

«para ser gentiles hombres, pintanse con bija que es una cosa colorada»

— Fernando de Oviedo

Further reading

- Campbell, Lyle (1997). American Indian languages: The historical linguistics of Native America. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-509427-1.

- Gordon Jr., Raymond G. (2005). Ethnologue: Languages of the world (15th ed.). Dallas, TX: SIL International. ISBN 1-55671-159-X. (Online version: http://www.ethnologue.com).

- Kaufman, Terrence (1994). "The native languages of South America", in C. Mosley & R. E. Asher (Eds.), Atlas of the world's languages (pp. 46–76). London: Routledge.