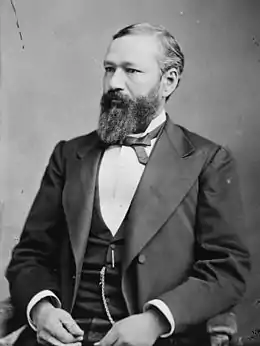

P. B. S. Pinchback

Pinckney Benton Stewart Pinchback (May 10, 1837 – December 21, 1921) was an American publisher, politician, and Union Army officer. Pinchback was the second African American (after Oscar Dunn) to serve as governor and lieutenant governor of a U.S. state. A Republican, Pinchback served as acting governor of Louisiana from December 9, 1872, to January 13, 1873. He was one of the most prominent African-American officeholders during the Reconstruction Era.

P. B. S. Pinchback | |

|---|---|

| |

| 24th Governor of Louisiana | |

| In office December 9, 1872 – January 13, 1873 | |

| Preceded by | Henry C. Warmoth |

| Succeeded by | John McEnery |

| 12th Lieutenant Governor of Louisiana | |

| In office December 6, 1871[1] – January 13, 1873 | |

| Governor | Henry C. Warmoth |

| Preceded by | Oscar Dunn |

| Succeeded by | Davidson Penn |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Pinckney Benton Stewart May 10, 1837 Macon, Georgia, U.S. |

| Died | December 21, 1921 (aged 84) Washington, D.C., U.S. |

| Political party | Republican |

| Spouse | Emily Hawthorne |

| Children | 6 |

| Education | Straight University (LLB) |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | United States |

| Branch/service | United States Army (Union Army) |

| Years of service | 1862–63 |

| Rank | Captain |

| Battles/wars | American Civil War |

Pinchback was born free in Macon, Georgia, to Eliza Stewart and her master, William Pinchback, a white planter. His father raised the younger Pinchback and his siblings as his own children on his large plantation in Mississippi. After the death of his father in 1848, his mother took Pinchback and siblings to the free state of Ohio to ensure their continued freedom. After the start of the American Civil War, Pinchback traveled to Union-occupied New Orleans. There he raised several companies for the 1st Louisiana Native Guard, and became one of the few African Americans commissioned as officers in the Union Army.

Pinchback remained in New Orleans after the Civil War, becoming active in Republican politics. He won election to the Louisiana State Senate in 1868 and became the president pro tempore of the state senate. He became the acting Lieutenant Governor of Louisiana following the death of Oscar Dunn in 1871 and briefly served as acting governor of Louisiana after Henry C. Warmoth was impeached. After the contested 1872 Louisiana gubernatorial election, Republican legislators elected Pinchback to the United States Senate. Due to the controversy over the 1872 elections in the state, which were challenged by white Democrats, Pinchback never seated in Congress.

Pinchback served as a delegate to the 1879 Louisiana constitutional convention, where he helped gain support for the founding of Southern University. In a Republican federal appointment, he served as the surveyor of U.S. customs of New Orleans from 1882 to 1885. Later he worked with other leading men of color to challenge the segregation of Louisiana's public transportation system, leading to the Supreme Court case of Plessy v. Ferguson. To escape increasing racial oppression, he moved with his family to Washington, D.C. in 1892, where they were among the elite people of color. He died there in 1921.

Early life

Pinckney Benton Stewart was born free in May 1837 in Macon, Bibb County, Georgia. His parents were Eliza Stewart, a former slave, and Major William Pinchback, a white planter and his mother's former master. William Pinchback, who also had a legal white family, freed Eliza and her two surviving children in 1836; she had borne six children by that point and two had survived.[2] She had four more children with Pinchback, all born into freedom under Georgia law because she was free.

Pinckney Stewart's parents were of diverse ethnic origins. Eliza Stewart was classified as mulatto and had African, Cherokee, Welsh and German ancestry. William Pinchback was ethnic European-American, of Scots-Irish, Welsh and German American ancestry.[3] Shortly after Pinckney's birth, his father William purchased a much larger plantation in Mississippi, and he moved there with both his white and mixed-race families.

Pinckney Benton Stewart and his siblings were considered the "natural" (or illegitimate) children of their father, but they were brought up in relatively affluent surroundings. He treated them as his own, with privileges similar to the white children on his plantation. In 1846, Pinchback sent the nine-year-old Pinckney and his older brother Napoleon north for education at a private academy,[2] Gilmore High School in Cincinnati, Ohio.[4] In 1848, when Pinckney was eleven, his father died.[2]

Fearful that the other Pinchback relatives might try to claim her children as slaves, Eliza Stewart fled with the children to Cincinnati in the free state of Ohio. Napoleon, at 18, helped to keep the family together, but he broke down under the responsibility.[2] At 12, Pinckney left school and began to work as a cabin boy on river and canal boats to help his family. For a while, he lived in Terre Haute, Indiana, where he worked as a hotel porter. During that time, he still identified as Pinckney B. Stewart. He did not take his father's surname of Pinchback until after the end of the Civil War.

Marriage and family

In 1860, at the age of 23, Pinckney married Emily Hawthorne, a free woman of color.[2] Like Stewart, she was "practically white" in appearance, meaning that she had a high proportion of European ancestors.[2] They had six children: Pinckney Napoleon in 1862, Bismarck in 1864, Nina in 1866, and Walter Alexander in 1868. Two others died young. Pinckney named one son Bismarck because of his admiration for statesman Otto von Bismarck of Germany, whom he considered to be one of the world's greatest men. Pinckney's mother, Eliza Stewart, lived with Pinckney and his family from 1867 until her death in 1884.[5]

They had a fine house in New Orleans. Usually, in the summer, the whole family traveled to Saratoga Springs, New York, a resort town in upstate, where they would stay for several weeks. Pinchback liked to gamble on the horse racing held there during the summer season.[5]

Military service and Civil War

The Civil War began the following year, and Pinckney Stewart decided to fight on the side of the Union. In 1862, he made his way to New Orleans, which had just been captured by the Union Army. He raised several companies for the Union's all-black 1st Louisiana Native Guards Regiment, which was garrisoned in the city. A minority of the men were Louisiana free men of color, part of the educated class before the war who had participated in the state militia. Most of the Guards were former slaves, who had escaped to join the Union forces and gain freedom.[6]

Commissioned a captain, Stewart was one of the Union Army's few commissioned officers of African-American ancestry. Like Stewart, the officers were mostly of mixed race. Most of them were drawn from the class of free people of color in New Orleans established before the war; unlike him, they were usually of colonial French and African descent. He became Company Commander of Company A, 2nd Louisiana Regiment Native Guard Infantry, made up mostly of refugee slaves. (It was later reformed as the 74th U.S. Colored Infantry Regiment, of the United States Colored Troops.)[7]

Passed over twice for promotion and tired of the prejudice he encountered from white officers, Stewart resigned his commission in 1863. In a letter of April 30, 1863, his married sister Adeline B. Saffold wrote to him from Sidney, Ohio, urging him to follow her example and enter the white world:

If I were you, Pink, I would not let my ambition die. I would seek to rise and not in that class either but I would take my position in the world as a white man as you are and let the other go for be assured of this as the other you will never get your rights. ...[2]

After the war, Stewart and his wife moved to Alabama.

Political career

After the war in New Orleans, Stewart took his father's surname of Pinchback. He became active in the Republican Party. The exact moment Pinchback decided to enter politics is described by George Devol in his book Forty Years a Gambler on the Mississippi.[8] In 1867, Pinchback organized the Fourth Ward Republican Club in New Orleans soon after Congress passed the Reconstruction Acts. That year, he was elected as a delegate to the constitutional convention.

In 1868 Pinchback was elected as a State Senator. He was elected as senate president pro tempore; seven of 36 seats in the Senate were held by men of color. The House had 42 representatives of African-American descent, comprising half the seats. (At the time, the populations of African Americans, including former free people of color, and whites in the state were nearly equal.)

As Senate president pro tempore, in 1871, Pinchback succeeded to the position of acting lieutenant governor upon the death of Oscar Dunn,[9][10] the first elected African-American lieutenant governor of a US state.[11]

Pinchback contributed further to the political discussion with the founding of the bi-weekly newspaper, the Louisianian in 1870. He worked as an editor there until 1872. Later, in 1874, he returned to be editor and in 1878 he became editor-in-chief, though he allowed students from Straight University (later part of Dillard University). The paper's motto was "Republican at all times, and under all circumstances." Publication of the paper ended in 1882.[12][13]

He was appointed as director of the New Orleans public schools. Statewide public schools were established for the first time by the new state legislature during Reconstruction.[14] Pinchback had a long-standing interest in education of blacks and was appointed to the Louisiana State Board of Education, where he served from March 18, 1871, until March, 1877.[15]

Ascension to Governorship

In 1872, the legislature filed impeachment charges against the incumbent Republican governor, Henry Clay Warmoth, over disputes over certifying returns of the disputed gubernatorial election, in which both Democrat John McEnery and Republican William Kellogg claimed victory. Trying to support a centrist fusion government at a time of divisions among Republicans, Warmoth had supported his appointed return board, which certified McEnery as winner. Republicans opposed this outcome and appointed their own returns board, which certified Kellogg. The election had been marked by violence and fraud. Pinchback rose to acting governor in Warmoth's stead by way of article 53 of the Louisiana Constitution of 1868, which held that the lieutenant governor would assume the duties of the governor "in case of impeachment of the Governor, his removal from office, death . . . resignation or absence from the state."[16] Pinchback was sworn in as the first governor of African descent in the history of the United States.[17][18][19] He took the oath as acting governor on December 9, 1872 and served for about six weeks, until the end of Warmoth's term.[20] Warmoth was not convicted, and the charges were eventually dropped by the legislature.

Also in 1872, at a national convention of African-American politicians, Pinchback had a public disagreement with Jeremiah Haralson of Alabama. James T. Rapier, also of Alabama, submitted a motion that the convention condemn all Republicans who had opposed President Ulysses S. Grant in that year's election.[21] Haralson supported the motion, but Pinchback opposed it because Senator Charles Sumner of Massachusetts would have been condemned for opposing Grant. Pinchback admired Sumner as a lifelong anti-slavery fighter.

1870s congressional elections

After his brief period in executive office, Pinchback remained active in politics and public service in Louisiana. From 1868, campaigns and elections in Louisiana were increasingly marked by Democratic violence. Historian George C. Rable described the White League, a paramilitary group started in 1874, as the "military arm of the Democratic Party."[22] The paramilitary group used intimidation and violence to suppress black voting and run Republicans out of office.

As an outcome of the controversial 1872 election, four U.S. seats from Louisiana were also contested, including Pinchback's seat in the at-large position. In early 1873, both the Republican William Kellogg-allied state legislators, who had a slight majority, and the Democrat John McEnery-allied legislators elected U.S. Senators. Pinchback was elected by the Republicans and presented the Senate with his credentials. The Democratic candidate also presented credentials. As the 1872 gubernatorial contest had involved the national government, Congress was initially reluctant to assess these issues. The contested claim was not settled for years, at a time when Democrats controlled Congress.

Holding out for the Senate seat, Pinchback decided not to take the House seat even though Congress was inclined to seat him while the contest of the election was decided. The 45th Congress (1877–1879), which finally decided the issue, had a Democratic majority and voted against Pinchback. The Senate awarded him compensation of $16,000 for his salary and mileage after his protracted struggle to take his seat.[23] The House also ruled against him, but not until the last day of Congress.[24]

In his memoir of Reconstruction, former Louisiana governor Henry Clay Warmoth wrote that the federal government was reluctant to seat people representing the Kellogg-Pinchback faction. He had a personal interest, as he had been forced out of Louisiana after allying with white conservatives in the 1872 election certification.[25] Historian John C. Rodrigue notes that the Committee on Elections was dealing with its own internal issues. It had accepted Pinchback's claim to the House seat, but he was holding out for the Senate seat. Complications arose after the Democrats took control of the next Congress and upheld election of his opponent.[25]

Overall, the mid-to-late 1870s marked an acceleration of the reversal of the political gains that African Americans in Louisiana had achieved since the end of the Civil War. In 1877, Democrats fully regained control of the state legislature after the withdrawal of federal troops, as a result of a national Democratic compromise marking the end of Reconstruction. Republican blacks continued to be elected to state and local offices, but elections were accompanied by violence and fraud. Most blacks were totally disfranchised by a new state constitution in 1898 and were effectively excluded from politics for decades.

Pinchback served as a delegate to the 1879 state constitutional convention; he and two other Republican African-American delegates, Theophile T. Allain, and Henry Demas, were credited with gaining support to establish Southern University, a historically black college in New Orleans, which was chartered in 1880. Pinchback was appointed as a member of Southern University's Board of Trustees (later redesignated the Board of Supervisors). The college relocated to the capital, Baton Rouge, in 1914.[26] At the 1876 Republican National Convention in Cincinnati, Pinchback gave a speech seconding the nomination of Oliver P. Morton for the presidency.[27] Pinchback was a delegate to the 1880 Republican National Convention.[15]

In 1882, the national Republican administration appointed Pinchback as surveyor of customs in New Orleans, a politically significant position in which he served until 1885.[28] It was his last political position.

Later life

In 1885, Pinchback studied law in New Orleans at Straight University, a historically black college later known as Dillard University. He was admitted to the Louisiana bar in 1886, but he never practiced.[28]

Pinchback moved with his family to Washington, D.C., in 1892. Wealthy from his positions and settlement on the Senate seat, he had a large mansion built off Fourteenth Street near the Chinese embassy.[23] At the time, his oldest son, Pinckney Pinchback, was established as a pharmacist in Philadelphia; the younger three ranged in age from 22 to 26 and were still living at home.[29] The Pinchback family was part of the mixed-race elite in Washington; people in the group had generally been free before the Civil War and often were educated and had acquired property. The Washington Post covered Pinchback's housewarming reception and his many high-ranking guests.[23]

Later, Pinchback worked for a time in New York as a U.S. Marshal.[28]

By his death in 1921 in Washington, D.C., Pinchback was little known politically.[28] His body was returned to New Orleans, where he was interred in Metairie Cemetery.

Legacy

Pinchback and his wife Nina were the maternal grandparents of Jean Toomer.[23] Their daughter Nina Pinchback Toomer returned to live with her parents after her husband abandoned her when Jean was an infant. They helped raise him, and he started school in Washington, D.C.. After his mother remarried, they moved to New Rochelle, New York. He returned to his grandparents after his mother died in 1909, and went to high school at the academic M Street School. As an adult, Toomer became a poet and writer who was prominent as a modernist in New York during the Harlem Renaissance.

See also

- List of African-American officeholders during Reconstruction

- List of African-American United States representatives

- List of African-American United States senators

- List of minority governors and lieutenant governors in the United States

- Military history of African Americans in the American Civil War

- David Paterson

- Deval Patrick

- Douglas Wilder

References

- Uncivil War: Five New Orleans Street Battles and the Rise and Fall of Radical Reconstruction by James K. Hogue

- Cynthia Earl Kerman, The Lives of Jean Toomer: A Hunger for Wholeness, LSU Press, 1989, pp. 15–18

- Toomer, Turner (1980), p. 22

- Shotwell, John Brough (1902). A history of the schools of Cincinnati. The School life company. pp. 453–455.

- Kerman (1989), The Lives of Jean Toomer, p. 23

- Terry L. Jones (2012-10-19) "The Free Men of Color Go to War" – NYTimes.com. Opinionator.blogs.nytimes.com. Retrieved 2012-12-18.

- Hollandsworth 1995, p. 122.

- George Devol, Forty Years a Gambler on the Mississippi, p. 216.

- Gates, Henry Louis (November 7, 2013). "P.B.S. Pinchback. The Black Governor Who Almost Was a Senator". PBS.

- "Louisiana creates award in honor of former La. governor, P.B.S Pinchback". WBRZ.org. June 6, 2021.

- Hodge, Channon (March 3, 2021). "The Capitol riot is an eerie repeat of this tense era in American history". CNN.

- "The Louisianian, Semi-weekly Louisianian and The Weekly Louisianian". Library of Congress. Louisiana State University. Retrieved 22 April 2021.

- "About The weekly Louisianian. [volume] (New Orleans, La.) 1872–1882". Library of Congress. National Endowment for the Humanities. Retrieved 22 April 2021.

- Kerman (1989), The Lives of Jean Toomer, pp. 19–20

- Simmons, William J., and Henry McNeal Turner. Men of Mark: Eminent, Progressive and Rising. GM Rewell & Company, 1887. pp. 759–781

- Louisiana Constitution of 1868.

- "Jan. 13th, 1990: First elected black governor in U.S. takes office". CBS News. 13 January 2016.

- "Pinckney Benton Stewart Pinchback". 14 January 2008.

- Gates, Henry Louis; Root, Jr | Originally posted on The (November 7, 2013). "P.B.S. Pinchback. The Black Governor Who Almost Was a Senator". PBS.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Cowan, Walter Greaves; McGuire, Jack B (2008-08-01). Louisiana Governors: Rulers, Rascals, and Reformers. Univ. Press of Mississippi. pp. 107–108. ISBN 9781934110904.

- See 1872 United States presidential election for more information about that election

- George C. Rable, But There Was No Peace: The Role of Violence in the Politics of Reconstruction, Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1984, p. 132

- Kent Anderson Leslie and Willard B. Gatewood Jr. "'This Father of Mine ... a Sort of Mystery': Jean Toomer's Georgia Heritage", Georgia Historical Quarterly 77 (winter 1993)

- "Two House Members Served for Only One Day". Retrieved 4 January 2023.

- Henry Clay Warmoth, War, Politics, and Reconstruction: Stormy Days in Louisiana, "Introduction" by John C. Rodrigue, Univ of South Carolina Press, 1930/2006

- Southern University at New Orleans, now under the same Board of Supervisors as Southern University and part of its statewide system, was developed later.

- David Saville Muzzey, James G. Blaine: A Political Idol of Other Days, p.106, Dodd, Mead & Co., 1934. Muzzey described Pinchback, without explanation, as "disreputable." Ibid.

- Ingham, John N; Feldman, Lynne B (1994). African-American Business Leaders: A Biographical Dictionary. Greenwood Publishing. pp. 560–562. ISBN 9780313272530.

- Kerman (1989), The Lives of Jean Toomer, p.24

Further reading

- Dray, Philip. Capitol men: the epic story of Reconstruction through the lives of the first Black congressmen (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2010).

- Grosz, Agnes Smith, "The Political Career of Pinckney Benton Stewart Pinchback," Louisiana Historical Quarterly, XXVII (1944)

- Haskins, James. Pinckney Benton Stewart Pinchback(New York: Macmillan, 1973)

- Hollandsworth, James G. (1998). The Louisiana Native Guards: The Black Military Experience During the Civil War. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press. ISBN 0-8071-2336-6.

- Patler, Nicholas (2012). "The Startling Career of P.B.S. Pinchback: A Whirlwind Crusade to Bring Equality to Reconstructed Louisiana," pp 211-233, in Matthew Lynch, ed., Before Obama: A Reappraisal of Black Reconstruction Era Politicians. Santa Barbara, CA: Praegar Publishing. ISBN 978-0-313-39791-2.

- Pinckney Benton Stewart Pinchback Papers, Manuscript Department, Moorland-Spingarm Research Center, Howard University, Washington, D.C., 3 includes "Here under the protecting care" speech quoted by Nicholas Lemann in Redemption: The Last Battle of the Civil War

- Men of Mark: Eminent, Progressive and Rising, by Rev. William J. Simmons, D. D., President of the State University, Louisville, Kentucky (1887)

- Paterson, David "Black, Blind, & In Charge: A Story of Visionary Leadership and Overcoming Adversity."Skyhorse Publishing. New York, New York, 2020

- Toomer, Jean; Turner, Darwin T. (1980). The Wayward and the Seeking: A Collection of Writings by Jean Toomer. Baton Rouge: Howard University Press. ISBN 0-88258-014-0.

External links

- State of Louisiana – Biography

- Cemetery Memorial by La-Cemeteries

- "Pinckney Benton Stewart "P.B.S." Pinchback". Civil War Union Officer & Louisiana Governor. Find a Grave. January 23, 2002. Retrieved December 9, 2012.