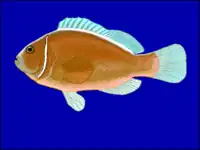

Pink skunk clownfish

The pink skunk clownfish (Amphiprion perideraion), also known as the pink anemonefish, is a species of anemonefish that is widespread from northern Australia through the Malay Archipelago and Melanesia.[2] Like all anemonefishes, it forms a symbiotic mutualism with sea anemones and is unaffected by the stinging tentacles of the host. It is a sequential hermaphrodite with a strict size-based dominance hierarchy; the female is largest, the breeding male is second largest, and the male nonbreeders get progressively smaller as the hierarchy descends.[3] They exhibit protandry, meaning the breeding male changes to female if the sole breeding female dies, with the largest nonbreeder becoming the breeding male.[2]

| Pink skunk clownfish | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Actinopterygii |

| Family: | Pomacentridae |

| Genus: | Amphiprion |

| Species: | A. perideraion |

| Binomial name | |

| Amphiprion perideraion Bleeker, 1855 | |

Description

The body of A. perideraion is pink to peach. It has the white stripe along the dorsal ridge that is common to all members of the skunk complex and a white head bar running vertically just behind the eye.[2] While the largest species of anemonefish can reach a length of 18 cm (7.1 in), A. perideraion is one of the smallest species, with females growing to a length of 10 cm (3.9 in).[2]

Color variations

Some anemonefish species have color variations based on geographic location, sex, and host anemone. A. perideraion, like other members of the skunk complex, does not show any of these variations.[2]

Similar species

A. perideraion is included in the skunk complex, so has similarities with other species in this complex. The combination of dorsal stripe and head bar distinguishes it from most other species. A. akallopisos, A. sandaracinos, and A. pacificus all lack a white head bar, while A. nigripes lacks the dorsal stripe and has black belly and black pelvic and anal fins. The hybrid A. leucokranos has a broader head bar and the dorsal stripe does not extend the full length of the dorsal ridge.[2]

A. perideraion showing the distinctive narrow head bar and dorsal stripe

A. perideraion showing the distinctive narrow head bar and dorsal stripe A. perideraion hovering above purple-tip anemone

A. perideraion hovering above purple-tip anemone A. akallopisos (skunk anemonefish) lacks a white head bar.

A. akallopisos (skunk anemonefish) lacks a white head bar. A. sandaracinos (orange anemonefish) lacks a white head bar.

A. sandaracinos (orange anemonefish) lacks a white head bar. The hybrid A. leucokranos has a white bonnet that does not extend the length of the dorsal ridge.

The hybrid A. leucokranos has a white bonnet that does not extend the length of the dorsal ridge. A. nigripes (Maldive anemonefish) lacks the dorsal strip and has a black belly, pelvic and anal fins.

A. nigripes (Maldive anemonefish) lacks the dorsal strip and has a black belly, pelvic and anal fins.

Distribution and habitat

A. perideraion is found throughout the Malay Archipelago and Melanesia, in the west Pacific Ocean from the Great Barrier Reef and Tonga, north to the Ryukyu Islands of Japan and in the eastern Indian Ocean from Ningaloo Reef, Western Australia, through the Rowley Shoals, Scott and Ashmore Reefs, Cocos and Christmas Islands to Sumatra. It inhabits reef lagoons and outer reef slopes.[4] A. perideraion has been thought to be found at depths of 3–20 m,[4] but surveys using autonomous underwater vehicles of mesophotic reefs at Viper Reef and Hydrographers Passage in the central Great Barrier Reef observed A. perideraion at depths between 50 and 65 m.[5] A. perideraion and A. clarkii are the only anemonefish found on both the east and west coasts of Australia.[2]

While the morphological features of A. perideraion are consistent throughout its range, genetic analysis of fish in the Indo-Malay Archipelago has shown a genetic break between the Java Sea population (Karimun Java) and all other locations. A north-to-south connection exists from the Philippines to the rest of the archipelago and a mixing of central populations along the strong current of the Indonesian throughflow.[6]

Host anemones

The relationship between anemonefish and their host sea anemones is not random and instead is highly nested in structure.[7] A. perideraion is a generalist, consistent with its widespread distribution, being hosted by the following four of the 10 host anemones: [2][4][7]

- Heteractis crispa sebae anemone

- Heteractis magnifica magnificent sea anemone (usually)

- Macrodactyla doreensis long-tentacle anemone

- Stichodactyla gigantea giant carpet anemone

Unusually for anemonefish, A. perideraion has been observed sharing a host with other species, including A. clarkii [8] and A. akallopisos.[9]

Conservation status

Anemonefish and their host anemones are found on coral reefs and face similar environmental issues. Like corals, anemones contain intracellular endosymbionts, zooxanthellae, and can suffer from bleaching due to triggers such as increased water temperature or acidification. Local populations and genetic diversity remain vulnerable to high level of exploitation of these species and their host anemones by the global ornamental fish trade.[10] This species was not evaluated in the 2012 release of the IUCN Red List.

In aquaria

It has successfully been bred in an aquarium.[9] In an aquarium, hobbyists have fed the species brine shrimp, mysis shrimp, chopped shellfish, and dried algae.[9][11]

Gallery

Pink anemonefish at Bunaken National Park, Indonesia

Pink anemonefish at Bunaken National Park, Indonesia A. perideraion

A. perideraion Two pink skunk clownfish (A. perideraion) and their closed host anemone, in Komodo

Two pink skunk clownfish (A. perideraion) and their closed host anemone, in Komodo Several A. perideraion at Komodo

Several A. perideraion at Komodo A. perideraion in a bleached anemone near Batu Moncho

A. perideraion in a bleached anemone near Batu Moncho.jpg.webp) Pink anemonefish at Wakatobi National Park, Indonesia

Pink anemonefish at Wakatobi National Park, Indonesia

References

- Jenkins, A.; Carpenter, K.E.; Allen, G.; Yeeting, B. & Myers, R. (2017). "Amphiprion perideraion". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2017: e.T188340A1860821. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2017-2.RLTS.T188340A1860821.en. Retrieved 19 February 2022.

- Fautin, Daphne G.; Allen, Gerald R. (1997). Field Guide to Anemone Fishes and Their Host Sea Anemones. Western Australian Museum. ISBN 9780730983651. Archived from the original on 18 October 2014.

- Buston PM (May 2004). "Territory inheritance in clownfish". Proc. Biol. Sci. 271 (Suppl 4): S252–4. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2003.0156. PMC 1810038. PMID 15252999.

- Bray, Dianne. "Pink Anemonefish, Amphiprion perideraion". Fishes of Australia. Retrieved 30 September 2014.

- Bridge, T.; Scott. A.; Steinberg, D. (2012). "Abundance and diversity of anemonefishes and their host sea anemones at two mesophotic sites on the Great Barrier Reef, Australia". Coral Reefs. 31 (4): 1057–1062. Bibcode:2012CorRe..31.1057B. doi:10.1007/s00338-012-0916-x. S2CID 9154493.

- Dohna, T.; Timm, J.; Hamid, L.; Kochzius M. (April 2015). "Limited connectivity and a phylogeographic break characterize populations of the pink anemonefish, Amphiprion perideraion, in the Indo-Malay Archipelago: inferences from a mitochondrial and microsatellite loci". Ecology and Evolution. 5 (8): 1717–1733. doi:10.1002/ece3.1455. PMC 4409419. PMID 25937914.

- Ollerton J; McCollin D; Fautin DG; Allen GR. (2007). "Finding NEMO: nestedness engendered by mutualistic organization in anemonefish and their hosts". Proc R Soc B Biol Sci. 274 (1609): 591–598. doi:10.1098/rspb.2006.3758. PMC 1766375. PMID 17476781.

- Hattori, A. (April 1995). "Coexistence of two anemonefishes, Amphiprion clarkii and A. perideraion, which utilize the same host sea anemone" (PDF). Environmental Biology of Fishes. 42 (4): 345–353. doi:10.1007/BF00001464. S2CID 23522414.

- Tristan Lougher (2006). What Fish?: A Buyer's Guide to Marine Fish. Interpet Publishing. p. 19. ISBN 978-1-84286-118-9.

- Madduppa, H.HT.; Timm, J.; Kochzius M. (February 2014). "Interspecific, Spatial and Temporal Variability of Self-Recruitment in Anemonefishes". PLOS ONE. 9 (2): e90648. Bibcode:2014PLoSO...990648M. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0090648. PMC 3938785. PMID 24587406.

- "Pink Skunk Clownfish". Animal-World.com. Retrieved 29 September 2015.

External links

- "Amphiprion perideraion". Integrated Taxonomic Information System.

- Amphiprion perideraion. Bleeker, 1855. Retrieved through: World Register of Marine Species.

- Froese, Rainer; Pauly, Daniel (eds.) (2014). "Amphiprion rubrocinctus" in FishBase. November 2014 version.

- Pink skunk clownfish at Animal Diversity Web

- Photos of Pink skunk clownfish on Sealife Collection