Pitt–Hopkins syndrome

Pitt–Hopkins syndrome (PTHS) is a rare genetic disorder characterized by developmental delay, epilepsy, distinctive facial features, and possible intermittent hyperventilation followed by apnea.[1] Pitt-Hopkins syndrome can be marked by intellectual disabilities as well as problems with socializing.[2] It is part of the clinical spectrum of Rett-like syndromes.[3]

| Pitt–Hopkins syndrome | |

|---|---|

| |

| Boy with Pitt–Hopkins syndrome showing the characteristic facial features. A censorship bar was added to help keep the subject's identity private | |

| Specialty | Psychiatry, Medical genetics |

As more is learned about Pitt–Hopkins, the developmental spectrum of the disorder is widening, and can also include difficulties with anxiety, autism,[4] ADHD, and sensory disorders. It is associated with an abnormality within chromosome 18 which causes insufficient expression of the TCF4 gene.[5] Those with PTHS have reported high rates of self-injury and aggressive behaviors usually related to autism and their sensory disorders.[2]

PTHS has traditionally been associated with severe cognitive impairment, however true intelligence is difficult to measure given motor and speech difficulties. Thanks to augmentative communication and more progressive therapies, many individuals can achieve much more than initially thought. It has become clearer that there is a wider range of cognitive abilities in Pitt–Hopkins than reported in much of the scientific literature. Researchers have developed cell and rodent models to test therapies for Pitt–Hopkins.[6]

PTHS is estimated to occur in 1:11,000 to 1:41,000 people.[7]

Signs and symptoms

PTHS can be seen as early as childhood.[8]

The earliest signs in infants is the lower face and the high nasal root.[7]

The facial features are characteristic and include:[9]

- Broad nasal bridge with bulbous tip

- Wide mouth

- Cupid's bow philtrum

- Prominent ears

- Flat feet

- Overriding toes

- Fetal pads

- Short stature

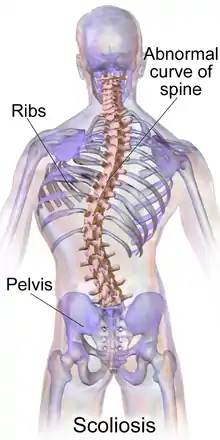

- Scoliosis

Adults who have PTHS may have trouble with their speech.[8] Craniofacial features, which are important when diagnosing PTHS, become more visible as the person gets older.[7]

PTHS is characterized by developmental delay, possible breathing problems of episodic hyperventilation and/or breath-holding while awake, recurrent seizures/epilepsy, gastrointestinal issues, and distinctive facial features. Stereotypic movements, particularly of the arms, wrists and fingers are almost universal. Hypotonia is common (75%), as is an unsteady gait. Other features include a single (simian) palmar crease, long, slender fingers, flat feet and cryptorchidism (in males). The presence of "fetal finger pads" is common. Hyperventilation may occur and is sometimes followed by apnea and cyanosis. Constipation is common. Microcephaly and seizures may occur. Hypopigmented skin macules have occasionally been reported. Individuals with Pitt–Hopkins syndrome typically have a happy, excitable demeanor with frequent smiling and laughter.

Genetics

The genetic cause of this disorder was described in 2007.[10] This disorder is due to a haploinsufficiency of the transcription factor 4 (TCF4) gene which is located on the long arm of chromosome 18 (18q21.2) The mutational spectrum appears to be 40% point mutations, 30% small deletions/insertions and 30% deletions. All appear to be de novo mutations. The risk in siblings is low, but higher than the general population due to parental germline mosaicism.[7]

A Pitt–Hopkins-like phenotype has been assigned to autosomal recessive mutations of the contactin associated protein like 2 (CNTNAP2) gene on the long arm of chromosome 7 (7q33-q36) and the neurexin 1 alpha (NRXN1) gene on the short arm of chromosome 2 (2p16.3).[11]

Malformations in the CNS can be seen in about 60 to 70% of patients on MRI scans.[12]

Pitt–Hopkins patients with a TCF4 deletion can lack the syndrome's characteristic facial features.[7]

Diagnosis

There is not a certain diagnostic criteria, but there are a few symptoms that support a diagnosis of PTHS. Some examples are: facial dysmorphism, early onset global developmental delay, moderate to severe intellectual disability, breathing abnormalities, and a lack of other major congenital abnormalities.[8]

Half of the individuals with PTHS are reported to have seizures, starting from childhood to the late teens.[7]

Around 50% of those affected show abnormalities on brain imaging. These include a hypoplastic corpus callosum with a missing rostrum and posterior part of the splenium, with bulbous caudate nuclei bulging towards the frontal horns.

Electroencephalograms show an excess of slow components.

According to the clinical diagnosis. PTHS is in the same group as Pervasive Developmental Disorders.[13]

When a patient is suspected of having PTHS, genetic tests looking at the TCF4 gene are typically done.[7]

Differential diagnosis

PTHS is symptomatically similar to Angelman syndrome, Rett syndrome and Mowat–Wilson syndrome.[12]

Angelman syndrome most closely resembles PTHS. Both have absent speech and a "happy" disposition. Of the differentials, Rett syndrome is the least close to PTHS. This syndrome is seen as a progressive encephalopathy. Both Angelman syndrome and Rett syndrome lack the distinctive facial features of PTHS. Mowat–Wilson syndrome is seen in early infancy and is characterized by distinctive facial abnormalities.[12]

Treatment

Currently there is no specific treatment for this condition. It is based on symptomatology. Since there is a lack of treatment, people with PTHS use behavioral and training approaches.[13]

Recommendations for developmental delay and intellectual disability in the U.S. (may differ depending on country):[7]

- Early intervention program from newborn to age 3 will allow access to different therapies (occupational, physical, speech, and feeding).

- Developmental preschool through public school systems from ages 3 to 5. The child will need an evaluation before getting into the program, to see what kind of therapy is needed.

- From the ages 5–21 the child's school may create an IEP (based on the child's functions and needs). Children are encouraged to stay in school until at least the age of 21.

History

The condition was first described in 1978 by D. Pitt and I. Hopkins (The Children's Cottages Training Centre, Kew and Royal Children's Hospital, Melbourne, Australia) in two unrelated patients.[14]

Professor Philip Beales, of the Institute of Child Health, has speculated that Peter the Wild Boy had Pitt–Hopkins syndrome.[15] The boy was brought to Britain in 1725 as a feral child.

See also

References

- Zweier C, Peippo MM, Hoyer J, Sousa S, Bottani A, Clayton-Smith J, et al. (May 2007). "Haploinsufficiency of TCF4 causes syndromal mental retardation with intermittent hyperventilation (Pitt-Hopkins syndrome)". American Journal of Human Genetics. 80 (5): 994–1001. doi:10.1086/515583. PMC 1852727. PMID 17436255.

- Watkins A, Bissell S, Moss J, Oliver C, Clayton-Smith J, Haye L, et al. (October 2019). "Behavioural and psychological characteristics in Pitt-Hopkins syndrome: a comparison with Angelman and Cornelia de Lange syndromes". Journal of Neurodevelopmental Disorders. 11 (1): 24. doi:10.1186/s11689-019-9282-0. PMC 6778364. PMID 31586495.

- Whalen S, Héron D, Gaillon T, Moldovan O, Rossi M, Devillard F, et al. (January 2012). "Novel comprehensive diagnostic strategy in Pitt-Hopkins syndrome: clinical score and further delineation of the TCF4 mutational spectrum". Human Mutation. 33 (1): 64–72. doi:10.1002/humu.21639. PMID 22045651. S2CID 9559486.

- "Pitt-Hopkins syndrome may point the way to autism treatments". Daniel R. Weinberger. May 2019.

- "Pitt-Hopkins". National Center for Biotechnology Information. Retrieved 2009-12-08.

- "A drug for autism? Potential treatment for Pitt-Hopkins syndrome offers clues; PTHS". The Conversation. 26 April 2019. Retrieved 2019-07-10.

- Sweetser DA, Elsharkawi I, Yonker L, Steeves M, Parkin K, Thibert R (1993). "Pitt-Hopkins Syndrome". In MP, Ardinger HH, Pagon RA, Wallace SE (eds.). GeneReviews. University of Washington, Seattle. PMID 22934316.

- Dean L (2012). "Pitt-Hopkins Syndrome". In Pratt VM, McLeod HL, Rubinstein WS, Scott SA, Dean LC, Kattman BL, et al. (eds.). Medical Genetics Summaries. National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI). PMID 28520343. Bookshelf ID: NBK66129.

- "Pitt-Hopkins Syndrome". Definitions. Qeios. 2020-02-02. doi:10.32388/nb53oy. S2CID 161843893. Retrieved 2022-10-16.

- Amiel J, Rio M, de Pontual L, Redon R, Malan V, Boddaert N, et al. (May 2007). "Mutations in TCF4, encoding a class I basic helix-loop-helix transcription factor, are responsible for Pitt-Hopkins syndrome, a severe epileptic encephalopathy associated with autonomic dysfunction". American Journal of Human Genetics. 80 (5): 988–993. doi:10.1086/515582. PMC 1852736. PMID 17436254.

- Peippo M, Ignatius J (April 2012). "Pitt-Hopkins Syndrome". Molecular Syndromology. 2 (3–5): 171–180. doi:10.1159/000335287. PMC 3366706. PMID 22670138.

- Marangi G, Zollino M (September 2015). "Pitt-Hopkins Syndrome and Differential Diagnosis: A Molecular and Clinical Challenge". Journal of Pediatric Genetics. 4 (3): 168–176. doi:10.1055/s-0035-1564570. PMC 4918722. PMID 27617128.

- Sweatt JD (May 2013). "Pitt-Hopkins Syndrome: intellectual disability due to loss of TCF4-regulated gene transcription". Experimental & Molecular Medicine. 45 (5): e21. doi:10.1038/emm.2013.32. PMC 3674405. PMID 23640545.

- Pitt D, Hopkins I (September 1978). "A syndrome of mental retardation, wide mouth and intermittent overbreathing". Australian Paediatric Journal. 14 (3): 182–4. doi:10.1111/jpc.1978.14.3.182. PMID 728011. S2CID 45629810.

- Megan Lane (8 August 2011). "Who was Peter the Wild Boy?". BBC News Magazine. BBC. Retrieved 2011-08-09.