Pizza theorem

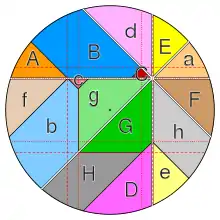

In elementary geometry, the pizza theorem states the equality of two areas that arise when one partitions a disk in a certain way.

The theorem is so called because it mimics a traditional pizza slicing technique. It shows that if two people share a pizza sliced into 8 pieces (or any multiple of 4 greater than 8), and take alternating slices, then they will each get an equal amount of pizza, irrespective of the central cutting point.

Statement

Let p be an interior point of the disk, and let n be a multiple of 4 that is greater than or equal to 8. Form n sectors of the disk with equal angles by choosing an arbitrary line through p, rotating the line n/2 − 1 times by an angle of 2π/n radians, and slicing the disk on each of the resulting n/2 lines. Number the sectors consecutively in a clockwise or anti-clockwise fashion. Then the pizza theorem states that:

- The sum of the areas of the odd-numbered sectors equals the sum of the areas of the even-numbered sectors (Upton 1968).

History

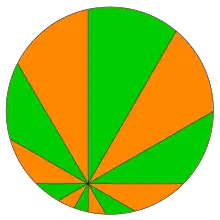

The pizza theorem was originally proposed as a challenge problem by Upton (1967). The published solution to this problem, by Michael Goldberg, involved direct manipulation of the algebraic expressions for the areas of the sectors. Carter & Wagon (1994a) provide an alternative proof by dissection. They show how to partition the sectors into smaller pieces so that each piece in an odd-numbered sector has a congruent piece in an even-numbered sector, and vice versa. Frederickson (2012) gave a family of dissection proofs for all cases (in which the number of sectors is 8, 12, 16, ...).

Generalizations

The requirement that the number of sectors be a multiple of four is necessary: as Don Coppersmith showed, dividing a disk into four sectors, or a number of sectors that is not divisible by four, does not in general produce equal areas. Mabry & Deiermann (2009) answered a problem of Carter & Wagon (1994b) by providing a more precise version of the theorem that determines which of the two sets of sectors has greater area in the cases that the areas are unequal. Specifically, if the number of sectors is 2 (mod 8) and no slice passes through the center of the disk, then the subset of slices containing the center has smaller area than the other subset, while if the number of sectors is 6 (mod 8) and no slice passes through the center, then the subset of slices containing the center has larger area. An odd number of sectors is not possible with straight-line cuts, and a slice through the center causes the two subsets to be equal regardless of the number of sectors.

Mabry & Deiermann (2009) also observe that, when the pizza is divided evenly, then so is its crust (the crust may be interpreted as either the perimeter of the disk or the area between the boundary of the disk and a smaller circle having the same center, with the cut-point lying in the latter's interior), and since the disks bounded by both circles are partitioned evenly so is their difference. However, when the pizza is divided unevenly, the diner who gets the most pizza area actually gets the least crust.

As Hirschhorn et al. (1999) note, an equal division of the pizza also leads to an equal division of its toppings, as long as each topping is distributed in a disk (not necessarily concentric with the whole pizza) that contains the central point p of the division into sectors.

Related results

Hirschhorn et al. (1999) show that a pizza sliced in the same way as the pizza theorem, into a number n of sectors with equal angles where n is divisible by four, can also be shared equally among n/4 people. For instance, a pizza divided into 12 sectors can be shared equally by three people as well as by two; however, to accommodate all five of the Hirschhorns, a pizza would need to be divided into 20 sectors.

Cibulka et al. (2010) and Knauer, Micek & Ueckerdt (2011) study the game theory of choosing free slices of pizza in order to guarantee a large share, a problem posed by Dan Brown and Peter Winkler. In the version of the problem they study, a pizza is sliced radially (without the guarantee of equal-angled sectors) and two diners alternately choose pieces of pizza that are adjacent to an already-eaten sector. If the two diners both try to maximize the amount of pizza they eat, the diner who takes the first slice can guarantee a 4/9 share of the total pizza, and there exists a slicing of the pizza such that he cannot take more. The fair division or cake cutting problem considers similar games in which different players have different criteria for how they measure the size of their share; for instance, one diner may prefer to get the most pepperoni while another diner may prefer to get the most cheese.

Higher dimensions

Brailov (2021), Brailov (2022), Ehrenborg, Morel & Readdy (2022) extends this result to higher dimensions, i.e. for certain arrangements of hyperplanes, the alternating sum of volumes cut out by the hyperplanes is zero.

Compare with the ham sandwich theorem, a result about slicing n-dimensional objects. The two-dimensional version implies that any pizza, no matter how misshapen, can have its area and its crust length simultaneously bisected by a single carefully chosen straight-line cut. The three-dimensional version implies the existence of a plane cut that equally shares base, tomato and cheese.

See also

- The lazy caterer's sequence, a sequence of integers that counts the maximum number of pieces of pizza that one can obtain by a given number of straight slices

References

- Carter, Larry; Wagon, Stan (1994a), "Proof without Words: Fair Allocation of a Pizza", Mathematics Magazine, 67 (4): 267, doi:10.1080/0025570X.1994.11996228, JSTOR 2690845.

- Carter, Larry; Wagon, Stan (1994b), "Problem 1457", Mathematics Magazine, 67 (4): 303–310, JSTOR 2690855.

- Cibulka, Josef; Kynčl, Jan; Mészáros, Viola; Stolař, Rudolf; Valtr, Pavel (2010), "Solution of Peter Winkler's pizza problem", Fete of Combinatorics and Computer Science, Bolyai Society Mathematical Studies, vol. 20, János Bolyai Mathematical Society and Springer-Verlag, pp. 63–93, arXiv:0812.4322, doi:10.1007/978-3-642-13580-4_4, ISBN 978-3-642-13579-8, S2CID 18272355.

- Brailov, Yury (2021), "Reflection groups and the pizza theorem", Algebra i Analiz (in Russian), 33 (6): 1–8

- Brailov, Yury (2022), "Reflection groups and the pizza theorem", St. Petersburg Math. J., 33 (6): 891–896, doi:10.1090/spmj/1732, S2CID 253334994

- Ehrenborg, Richard; Morel, Sophie; Readdy, Margaret (June 3, 2022), "Sharing pizza in 𝑛 dimensions", Transactions of the American Mathematical Society, 375 (8): 5829–5857, arXiv:2102.06649, doi:10.1090/tran/8664, ISSN 0002-9947

- Hirschhorn, J.; Hirschhorn, M. D.; Hirschhorn, J. K.; Hirschhorn, A. D.; Hirschhorn, P. M. (1999), "The pizza theorem" (PDF), Austral. Math. Soc. Gaz., 26: 120–121.

- Frederickson, Greg (2012), "The Proof Is in the Pizza", Mathematics Magazine, 85 (1): 26–33, doi:10.4169/math.mag.85.1.26, JSTOR 10.4169/math.mag.85.1.26, S2CID 116636161.

- Knauer, Kolja; Micek, Piotr; Ueckerdt, Torsten (2011), "How to eat 4/9 of a pizza", Discrete Mathematics, 311 (16): 1635–1645, arXiv:0812.2870, doi:10.1016/j.disc.2011.03.015, S2CID 15566728.

- Mabry, Rick; Deiermann, Paul (2009), "Of Cheese and Crust: A Proof of the Pizza Conjecture and Other Tasty Results", American Mathematical Monthly, 116 (5): 423–438, doi:10.4169/193009709x470317, JSTOR 40391118.

- Ornes, Stephen (December 11, 2009), "The perfect way to slice a pizza", New Scientist.

- Upton, L. J. (1967), "Problem 660", Mathematics Magazine, 40 (3): 163, JSTOR 2688484. Problem statement

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link). - Upton, L. J. (1968), "Problem 660", Mathematics Magazine, 41 (1): 42, JSTOR 2687962. Solution by Michael Goldberg

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link). - Berzsenyi, George (1994), "The Pizza Theorem - Part I" (PDF), Quantum Magazine: 29

- Berzsenyi, George (1994), "The Pizza Theorem - Part II" (PDF), Quantum Magazine: 29

External links

- Weisstein, Eric W. "Pizza Theorem". MathWorld.

- Sillke, Torsten, Pizza Theorem, retrieved 2009-11-24