Limbourg brothers

The Limbourg brothers (Dutch: Gebroeders van Limburg or Gebroeders Van Lymborch; fl. 1385 – 1416) were Dutch miniature painters (Herman, Paul, and Jean) from the city of Nijmegen. They were active in the early 15th century in France and Burgundy, working in the International Gothic style.

They created what is certainly the best-known late medieval illuminated manuscript, the Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry.

Family background and early life

A Johannes de Lymborgh appears in mid-14th century archives. He may have come from Limbourg on the Meuse to Nijmegen, then the capital of the duchy of Gelre, and appears to be the father of Arnold de Limbourch, a wood carver and sculptor whose name also appears in medieval archives. In 1385 Arnold married Mechteld Maelwael or Maloeul.[1] She came from a family of craftsmen and painters. Her father and uncle were painters in the employ of the Duke of Guelders, as gilders and as painters of heraldic devices. It was as a heraldic painter that Mechteld's brother Jean Malouel received a commission in Paris by Isabeau of Bavaria in 1396, regent regent to her husband Charles VI of France. Within the year Maloul accepted the position as valet de chambre and court painter to Charles's uncle Philip the Bold, the Duke of Burgundy.[2]

Arnold and Mechteld had six children over the next decade: the three boys, Herman, Paul, and Jean were born between c. 1385 and c. 1388; two more boys in the early 1390s and a daughter in the mid-1390s. In the late 1390s (probably around 1398) Herman and Jean were sent to Paris,[1] where records from 1399 document them as apprentices to a Parisian goldsmith, a position possibly organized by their uncle. That year the goldsmith sent the boys home to Guelders during an outbreak of disease in Paris. They were captured and imprisoned in Brussels, probably because of a conflict between Brabant and Guelders, with their ransom set at 55 écus plus prison expenses. The boys' father had died that year leaving their mother destitute, unable to secure their release. Local guild members in Brussels tried to raise the funds, but six months passed, the boys were still in captives, when Philip the Bold paid the ransom in May of 1400.[3]

Philip the Bold

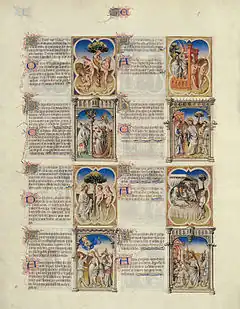

In February 1402 Paul and Jean were contracted by Philip to work for four years exclusively on illuminating a bible (a très belle et notable Bible).[1] It is their first documented commission and the work seems to have been executed in Paris. Art historians are divided as to whether the Bible Moralisée (Ms. fr. 166 in the Bibliothèque nationale de France in Paris is the same manuscript as Philip's commission;[4] although there is consensus that manuscript was executed by Jean and Pol Limbourg.[5]

A bible moralisée is a type of bible that emerged in the 13th century. It followed a specific format in which bible passages were paired with commentary or moralizations and an image, with each page containing four pairs of images meant to dominate the page. Typically such a bible contained more than 5000 painted miniatures; the cost and labor involved in such a production was so great that only royalty commissioned them. Manuscript 166 in Paris is an almost verbatim copy of the bible moralisee commissioned by Philip's father John II of France, known as Ms. fr. 167, which contains 5122 miniatures.[5]

The contract Philip executed with the brothers was quite specific: they were to provide miniatures (ystoires) as quickly as possible irrespective of holidays, to be paid a daily rate of 6 sous. Philip's physician, Jean Durant, was to supervise the effort, for which he received 600 francs and periodic repayments for lapis lazuli used to produce Illuminated manuscripts.[3] In 1404 the brothers are referred to as peintres et historieurs, whereas they were earlier referred to as painters (peintres) and illuminators (enlumineurs). They almost certainly painted the miniatures as well as the borders.[3] They completed folios 1-24 and the underdrawings to folio 32.[5]

The recorded documentation regarding specific commissions ends with Philip's death in April 1404. They are mentioned in some documents and inventories kept by Berry's valet de chambre and after 1408 in records regarding various payments and exchanges of gifts.[1]

Jean de Berry

After Philip's death, Herman, Paul, and Johan came to work for his brother John, Duke of Berry; an extravagant collector of the arts and books. Their first assignment was to illuminate a book of hours, now known as the Belles Heures du Duc de Berry, and today held in The Cloisters of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City.[6]

The illuminated manuscript was finished in 1409 much to the satisfaction of the duke, and he assigned them to an even more ambitious project for a book of hours. This became the Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry, widely regarded as the peak of late medieval book illumination, and possibly the most valuable book in the world. It is kept as Ms. 65 in the Musée Condé in Chantilly, France.

Paul especially was on good terms with the duke and was given a court position as valet de chambre, granting him access and status (his uncle had had the same position with the duke of Burgundy). The duke gave him jewelry and a large house in Bourges. Paul was attracted to a young girl, Gillette la Mercière, but her parents disapproved. The duke had the girl confined, and released her only on the king's command. In 1411 Paul and Gillette married anyway, but the marriage remained childless (the girl was 12, her husband 24 at the time).

Death

In the first half of 1416, Jean de Berry and the three Limbourg brothers – all not yet 30 years old – died, possibly of the plague, leaving the Très Riches Heures unfinished. An unidentified artist (possibly Barthélemy van Eyck) completed the calendar miniatures in the 1440s when the book apparently was in the possession of René d'Anjou, and in 1485 Jean Colombe finished the work for the House of Savoy.

The work of the Limbourg brothers, being mostly inaccessible, became forgotten until the 19th century. Nevertheless, they set an example for the next generations of painters, which extended beyond miniature painting. They worked in a Northern European tradition, but display influences from Italian models. Among their own sources of artistic inspiration was the work of the Master of the Brussels Initials.

References

- Husband (2008), 33-34

- Husband (2008), 279

- Meiss, 67-68

- Husband (2008), 36

- Dückers (2005), 85-86

- Husband (2008), p. x

Sources

- Rob Dückers and Pieter Roelofs (eds). The Limbourg brothers: Nijmegen masters at the French court, 1400–1416. Exhibition catalogue, Ludion, Nijmegen 2005. ISBN 90-5544-596-7

- Dückers, Rob; Pieter Roelofs (eds). The Limbourg Brothers. Brill, 2009. ISBN 9789004175129

- Husband, Timothy B., The Art of Illumination: The Limbourg Brothers and the Belles Heures of Jean de France, Duc de Berry. The Metropolitan Museum of Art/Yale University Press, 2008. ISBN 978-1-58839-294-7

- Lowden, John. (2005). "The Bible Moralisée in the Fifteenth Century and the Challenge of the Bible Historiale". Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes, Vol. 68, pp. 73-136

- Manion, Margaret M. (1995). "Psalter Illustration in the Très Riches Heures of Jean de Berry." Gesta (International Center of Medieval Art) vol. 34, no. 2, pp. 147–161.

- Meiss, Millard. French painting in the time of Jean de Berry : the Limbourgs and their contemporaries. Thames and Hudson, 1974. ISBN 0-500-23201-6

External links

- Website of the 2005 exhibition in Nijmegen

- Website of the annual medieval festival dedicated to the Limbourg brothers in Nijmegen

- Limbourg brothers last Illuminators of the Medieval Art