Earth radius

Earth radius (denoted as R🜨 or ) is the distance from the center of Earth to a point on or near its surface. Approximating the figure of Earth by an Earth spheroid, the radius ranges from a maximum of nearly 6,378 km (3,963 mi) (equatorial radius, denoted a) to a minimum of nearly 6,357 km (3,950 mi) (polar radius, denoted b).

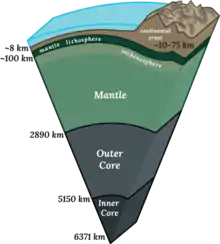

| Earth radius | |

|---|---|

Cross section of Earth's Interior | |

| General information | |

| Unit system | astronomy, geophysics |

| Unit of | distance |

| Symbol | R🜨, , |

| Conversions | |

| 1 R🜨 in ... | ... is equal to ... |

| SI base unit | 6.3781×106 m[1] |

| Metric system | 6,357 to 6,378 km |

| English units | 3,950 to 3,963 mi |

| Geodesy |

|---|

|

A nominal Earth radius is sometimes used as a unit of measurement in astronomy and geophysics, which is recommended by the International Astronomical Union to be the equatorial value.[1]

A globally-average value is usually considered to be 6,371 kilometres (3,959 mi) with a 0.3% variability (±10 km) for the following reasons. The International Union of Geodesy and Geophysics (IUGG) provides three reference values: the mean radius (R1) of three radii measured at two equator points and a pole; the authalic radius, which is the radius of a sphere with the same surface area (R2); and the volumetric radius, which is the radius of a sphere having the same volume as the ellipsoid (R3).[2] All three values are about 6,371 kilometres (3,959 mi).

Other ways to define and measure the Earth's radius involve the radius of curvature. A few definitions yield values outside the range between the polar radius and equatorial radius because they include local or geoidal topography or because they depend on abstract geometrical considerations.

Introduction

Earth's rotation, internal density variations, and external tidal forces cause its shape to deviate systematically from a perfect sphere.[lower-alpha 1] Local topography increases the variance, resulting in a surface of profound complexity. Our descriptions of Earth's surface must be simpler than reality in order to be tractable. Hence, we create models to approximate characteristics of Earth's surface, generally relying on the simplest model that suits the need.

Each of the models in common use involve some notion of the geometric radius. Strictly speaking, spheres are the only solids to have radii, but broader uses of the term radius are common in many fields, including those dealing with models of Earth. The following is a partial list of models of Earth's surface, ordered from exact to more approximate:

- The actual surface of Earth

- The geoid, defined by mean sea level at each point on the real surface[lower-alpha 2]

- A spheroid, also called an ellipsoid of revolution, geocentric to model the entire Earth, or else geodetic for regional work[lower-alpha 3]

- A sphere

In the case of the geoid and ellipsoids, the fixed distance from any point on the model to the specified center is called "a radius of the Earth" or "the radius of the Earth at that point".[lower-alpha 4] It is also common to refer to any mean radius of a spherical model as "the radius of the earth". When considering the Earth's real surface, on the other hand, it is uncommon to refer to a "radius", since there is generally no practical need. Rather, elevation above or below sea level is useful.

Regardless of the model, any radius falls between the polar minimum of about 6,357 km and the equatorial maximum of about 6,378 km (3,950 to 3,963 mi). Hence, the Earth deviates from a perfect sphere by only a third of a percent, which supports the spherical model in most contexts and justifies the term "radius of the Earth". While specific values differ, the concepts in this article generalize to any major planet.

Physics of Earth's deformation

Rotation of a planet causes it to approximate an oblate ellipsoid/spheroid with a bulge at the equator and flattening at the North and South Poles, so that the equatorial radius a is larger than the polar radius b by approximately aq. The oblateness constant q is given by

where ω is the angular frequency, G is the gravitational constant, and M is the mass of the planet.[lower-alpha 5] For the Earth 1/q ≈ 289, which is close to the measured inverse flattening 1/f ≈ 298.257. Additionally, the bulge at the equator shows slow variations. The bulge had been decreasing, but since 1998 the bulge has increased, possibly due to redistribution of ocean mass via currents.[4]

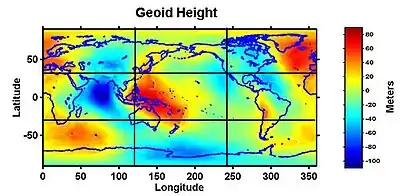

The variation in density and crustal thickness causes gravity to vary across the surface and in time, so that the mean sea level differs from the ellipsoid. This difference is the geoid height, positive above or outside the ellipsoid, negative below or inside. The geoid height variation is under 110 m (360 ft) on Earth. The geoid height can change abruptly due to earthquakes (such as the Sumatra-Andaman earthquake) or reduction in ice masses (such as Greenland).[5]

Not all deformations originate within the Earth. Gravitational attraction from the Moon or Sun can cause the Earth's surface at a given point to vary by tenths of a meter over a nearly 12-hour period (see Earth tide).

Radius and local conditions

Given local and transient influences on surface height, the values defined below are based on a "general purpose" model, refined as globally precisely as possible within 5 m (16 ft) of reference ellipsoid height, and to within 100 m (330 ft) of mean sea level (neglecting geoid height).

Additionally, the radius can be estimated from the curvature of the Earth at a point. Like a torus, the curvature at a point will be greatest (tightest) in one direction (north–south on Earth) and smallest (flattest) perpendicularly (east–west). The corresponding radius of curvature depends on the location and direction of measurement from that point. A consequence is that a distance to the true horizon at the equator is slightly shorter in the north–south direction than in the east–west direction.

In summary, local variations in terrain prevent defining a single "precise" radius. One can only adopt an idealized model. Since the estimate by Eratosthenes, many models have been created. Historically, these models were based on regional topography, giving the best reference ellipsoid for the area under survey. As satellite remote sensing and especially the Global Positioning System gained importance, true global models were developed which, while not as accurate for regional work, best approximate the Earth as a whole.

Extrema: equatorial and polar radii

The following radii are derived from the World Geodetic System 1984 (WGS-84) reference ellipsoid.[6] It is an idealized surface, and the Earth measurements used to calculate it have an uncertainty of ±2 m in both the equatorial and polar dimensions.[7] Additional discrepancies caused by topographical variation at specific locations can be significant. When identifying the position of an observable location, the use of more precise values for WGS-84 radii may not yield a corresponding improvement in accuracy.

The value for the equatorial radius is defined to the nearest 0.1 m in WGS-84. The value for the polar radius in this section has been rounded to the nearest 0.1 m, which is expected to be adequate for most uses. Refer to the WGS-84 ellipsoid if a more precise value for its polar radius is needed.

- The Earth's equatorial radius a, or semi-major axis, is the distance from its center to the equator and equals 6,378.1370 km (3,963.1906 mi).[8] The equatorial radius is often used to compare Earth with other planets.

- The Earth's polar radius b, or semi-minor axis, is the distance from its center to the North and South Poles, and equals 6,356.7523 km (3,949.9028 mi).

Location-dependent radii

Geocentric radius

The geocentric radius is the distance from the Earth's center to a point on the spheroid surface at geodetic latitude φ:

where a and b are, respectively, the equatorial radius and the polar radius.

The extrema geocentric radii on the ellipsoid coincide with the equatorial and polar radii. They are vertices of the ellipse and also coincide with minimum and maximum radius of curvature.

Radii of curvature

Principal radii of curvature

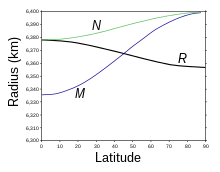

There are two principal radii of curvature: along the meridional and prime-vertical normal sections.

Meridional

In particular, the Earth's meridional radius of curvature (in the north–south direction) at φ is:[9]

where is the eccentricity of the earth. This is the radius that Eratosthenes measured in his arc measurement.

Prime vertical

If one point had appeared due east of the other, one finds the approximate curvature in the east–west direction.[lower-alpha 6]

This Earth's prime-vertical radius of curvature, also called the Earth's transverse radius of curvature, is defined perpendicular (orthogonal) to M at geodetic latitude φ[lower-alpha 7] and is:[9]

N can also be interpreted geometrically as the normal distance from the ellipsoid surface to the polar axis.[10] The radius of a parallel of latitude is given by .[11][12]

Polar and equatorial radius of curvature

The Earth's meridional radius of curvature at the equator equals the meridian's semi-latus rectum:

- b2/a = 6,335.439 km

The Earth's prime-vertical radius of curvature at the equator equals the equatorial radius, N = a.

The Earth's polar radius of curvature (either meridional or prime-vertical) is:

- a2/b = 6,399.594 km

Derivation

Extended content |

|---|

|

The principal curvatures are the roots of Equation (125) in:[13] where in the first fundamental form for a surface (Equation (112) in[13]): E, F, and G are elements of the metric tensor: , , in the second fundamental form for a surface (Equation (123) in[13]): e, f, and g are elements of the shape tensor: is the unit normal to the surface at , and because and are tangents to the surface, is normal to the surface at . With for an oblate spheroid, the curvatures are

and the principal radii of curvature are

The first and second radii of curvature correspond, respectively, to the Earth's meridional and prime-vertical radii of curvature. Geometrically, the second fundamental form gives the distance from to the plane tangent at . |

Azimuthal

The Earth's azimuthal radius of curvature, along an Earth normal section at an azimuth (measured clockwise from north) α and at latitude φ, is derived from Euler's curvature formula as follows:[14]: 97

Non-directional

It is possible to combine the principal radii of curvature above in a non-directional manner.

The Earth's Gaussian radius of curvature at latitude φ is:[14]

Where K is the Gaussian curvature, .

The Earth's mean radius of curvature at latitude φ is:[14]: 97

Global radii

The Earth can be modeled as a sphere in many ways. This section describes the common ways. The various radii derived here use the notation and dimensions noted above for the Earth as derived from the WGS-84 ellipsoid;[6] namely,

- Equatorial radius: a = (6378.1370 km)

- Polar radius: b = (6356.7523 km)

A sphere being a gross approximation of the spheroid, which itself is an approximation of the geoid, units are given here in kilometers rather than the millimeter resolution appropriate for geodesy.

Nominal radius

In astronomy, the International Astronomical Union denotes the nominal equatorial Earth radius as , which is defined to be 6,378.1 km (3,963.2 mi).[1]: 3 The nominal polar Earth radius is defined as = 6,356.8 km (3,949.9 mi). These values correspond to the zero Earth tide convention. Equatorial radius is conventionally used as the nominal value unless the polar radius is explicitly required.[1]: 4 The nominal radius serves as a unit of length for astronomy. (The notation is defined such that it can be easily generalized for other planets; e.g., for the nominal polar Jupiter radius.)

Arithmetic mean radius

In geophysics, the International Union of Geodesy and Geophysics (IUGG) defines the Earth's arithmetic mean radius (denoted R1) to be[2]

The factor of two accounts for the biaxial symmetry in Earth's spheroid, a specialization of triaxial ellipsoid. For Earth, the arithmetic mean radius is 6,371.0088 km (3,958.7613 mi).[15]

Authalic radius

Earth's authalic radius (meaning "equal area") is the radius of a hypothetical perfect sphere that has the same surface area as the reference ellipsoid. The IUGG denotes the authalic radius as R2.[2] A closed-form solution exists for a spheroid:[16]

where e2 = a2 − b2/a2 and A is the surface area of the spheroid.

For the Earth, the authalic radius is 6,371.0072 km (3,958.7603 mi).[15]

The authalic radius also corresponds to the radius of (global) mean curvature, obtained by averaging the Gaussian curvature, , over the surface of the ellipsoid. Using the Gauss–Bonnet theorem, this gives

Volumetric radius

Another spherical model is defined by the Earth's volumetric radius, which is the radius of a sphere of volume equal to the ellipsoid. The IUGG denotes the volumetric radius as R3.[2]

For Earth, the volumetric radius equals 6,371.0008 km (3,958.7564 mi).[15]

Rectifying radius

Another global radius is the Earth's rectifying radius, giving a sphere with circumference equal to the perimeter of the ellipse described by any polar cross section of the ellipsoid. This requires an elliptic integral to find, given the polar and equatorial radii:

The rectifying radius is equivalent to the meridional mean, which is defined as the average value of M:[16]

For integration limits of [0,π/2], the integrals for rectifying radius and mean radius evaluate to the same result, which, for Earth, amounts to 6,367.4491 km (3,956.5494 mi).

The meridional mean is well approximated by the semicubic mean of the two axes,

which differs from the exact result by less than 1 μm (4×10−5 in); the mean of the two axes,

about 6,367.445 km (3,956.547 mi), can also be used.

Topographical radii

The mathematical expressions above apply over the surface of the ellipsoid. The cases below considers Earth's topography, above or below a reference ellipsoid. As such, they are topographical geocentric distances, Rt, which depends not only on latitude.

Topographical extremes

- Maximum Rt: the summit of Chimborazo is 6,384.4 km (3,967.1 mi) from the Earth's center.

- Minimum Rt: the floor of the Arctic Ocean is 6,352.8 km (3,947.4 mi) from the Earth's center.[17]

Topographical global mean

The topographical mean geocentric distance averages elevations everywhere, resulting in a value 230 m larger than the IUGG mean radius, the authalic radius, or the volumetric radius. This topographical average is 6,371.230 km (3,958.899 mi) with uncertainty of 10 m (33 ft).[18]

Derived quantities: diameter, circumference, arc-length, area, volume

Earth's diameter is simply twice Earth's radius; for example, equatorial diameter (2a) and polar diameter (2b). For the WGS84 ellipsoid, that's respectively:

- 2a = 12,756.2740 km (7,926.3812 mi),

- 2b = 12,713.5046 km (7,899.8055 mi).

Earth's circumference equals the perimeter length. The equatorial circumference is simply the circle perimeter: Ce=2πa, in terms of the equatorial radius, a. The polar circumference equals Cp=4mp, four times the quarter meridian mp=aE(e), where the polar radius b enters via the eccentricity, e=(1−b2/a2)0.5; see Ellipse#Circumference for details.

Arc length of more general surface curves, such as meridian arcs and geodesics, can also be derived from Earth's equatorial and polar radii.

Likewise for surface area, either based on a map projection or a geodesic polygon.

Earth's volume, or that of the reference ellipsoid, is V = 4/3πa2b. Using the parameters from WGS84 ellipsoid of revolution, a = 6,378.137 km and b = 6356.7523142 km, V = 1.08321×1012 km3 (2.5988×1011 cu mi).[19]

Published values

This table summarizes the accepted values of the Earth's radius.

| Agency | Description | Value (in meters) | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|

| IAU | nominal "zero tide" equatorial | 6378100 | [1] |

| IAU | nominal "zero tide" polar | 6356800 | [1] |

| IUGG | equatorial radius | 6378137 | [2] |

| IUGG | semiminor axis (b) | 6356752.3141 | [2] |

| IUGG | polar radius of curvature (c) | 6399593.6259 | [2] |

| IUGG | mean radius (R1) | 6371008.7714 | [2] |

| IUGG | radius of sphere of same surface (R2) | 6371007.1810 | [2] |

| IUGG | radius of sphere of same volume (R3) | 6371000.7900 | [2] |

| IERS | WGS-84 ellipsoid, semi-major axis (a) | 6378137.0 | [6] |

| IERS | WGS-84 ellipsoid, semi-minor axis (b) | 6356752.3142 | [6] |

| IERS | WGS-84 ellipsoid, polar radius of curvature (c) | 6399593.6258 | [6] |

| IERS | WGS-84 ellipsoid, Mean radius of semi-axes (R1) | 6371008.7714 | [6] |

| IERS | WGS-84 ellipsoid, Radius of Sphere of Equal Area (R2) | 6371007.1809 | [6] |

| IERS | WGS-84 ellipsoid, Radius of Sphere of Equal Volume (R3) | 6371000.7900 | [6] |

| GRS 80 semi-major axis (a) | 6378137.0 | ||

| GRS 80 semi-minor axis (b) | ≈6356752.314140 | ||

| Spherical Earth Approx. of Radius (RE) | 6366707.0195 | [20] | |

| meridional radius of curvature at the equator | 6335439 | ||

| Maximum (the summit of Chimborazo) | 6384400 | [17] | |

| Minimum (the floor of the Arctic Ocean) | 6352800 | [17] | |

| Average distance from center to surface | 6371230±10 | [18] |

History

The first published reference to the Earth's size appeared around 350 BC, when Aristotle reported in his book On the Heavens[21] that mathematicians had guessed the circumference of the Earth to be 400,000 stadia. Scholars have interpreted Aristotle's figure to be anywhere from highly accurate[22] to almost double the true value.[23] The first known scientific measurement and calculation of the circumference of the Earth was performed by Eratosthenes in about 240 BC. Estimates of the accuracy of Eratosthenes's measurement range from 0.5% to 17%.[24] For both Aristotle and Eratosthenes, uncertainty in the accuracy of their estimates is due to modern uncertainty over which stadion length they meant.

Around 100 BC, Posidonius of Apamea recomputed Earth's radius, and found it to be close to that by Eratosthenes,[25] but later Strabo incorrectly attributed him a value about 3/4 of the actual size.[26] Claudius Ptolemy around 150 AD gave empirical evidence supporting a spherical Earth,[27] but he accepted the lesser value attributed to Posidonius. His highly influential work, the Almagest,[28] left no doubt among medieval scholars that Earth is spherical, but they were wrong about its size.

By 1490, Christopher Columbus believed that traveling 3,000 miles west from the west coast of the Iberian peninsula would let him reach the eastern coasts of Asia.[29] However, the 1492 enactment of that voyage brought his fleet to the Americas. The Magellan expedition (1519–1522), which was the first circumnavigation of the World, soundly demonstrated the sphericity of the Earth,[30] and affirmed the original measurement of 40,000 km (25,000 mi) by Eratosthenes.

Around 1690, Isaac Newton and Christiaan Huygens argued that Earth was closer to an oblate spheroid than to a sphere. However, around 1730, Jacques Cassini argued for a prolate spheroid instead, due to different interpretations of the Newtonian mechanics involved.[31] To settle the matter, the French Geodesic Mission (1735–1739) measured one degree of latitude at two locations, one near the Arctic Circle and the other near the equator. The expedition found that Newton's conjecture was correct:[32] the Earth is flattened at the poles due to rotation's centrifugal force.

See also

Notes

- For details see figure of the Earth, geoid, and Earth tide.

- There is no single center to the geoid; it varies according to local geodetic conditions.

- In a geocentric ellipsoid, the center of the ellipsoid coincides with some computed center of Earth, and best models the earth as a whole. Geodetic ellipsoids are better suited to regional idiosyncrasies of the geoid. A partial surface of an ellipsoid gets fitted to the region, in which case the center and orientation of the ellipsoid generally do not coincide with the earth's center of mass or axis of rotation.

- The value of the radius is completely dependent upon the latitude in the case of an ellipsoid model, and nearly so on the geoid.

- This follows from the International Astronomical Union definition rule (2): a planet assumes a shape due to hydrostatic equilibrium where gravity and centrifugal forces are nearly balanced.[3]

- East–west directions can be misleading. Point B, which appears due east from A, will be closer to the equator than A. Thus the curvature found this way is smaller than the curvature of a circle of constant latitude, except at the equator. West can be exchanged for east in this discussion.

- N is defined as the radius of curvature in the plane that is normal to both the surface of the ellipsoid at, and the meridian passing through, the specific point of interest.

References

- Mamajek, E. E; Prsa, A; Torres, G; et al. (2015). "IAU 2015 Resolution B3 on Recommended Nominal Conversion Constants for Selected Solar and Planetary Properties". arXiv:1510.07674 [astro-ph.SR].

- Moritz, H. (1980). Geodetic Reference System 1980, by resolution of the XVII General Assembly of the IUGG in Canberra.

- IAU 2006 General Assembly: Result of the IAU Resolution votes Archived 2006-11-07 at the Wayback Machine

- Satellites Reveal A Mystery Of Large Change In Earth's Gravity Field , Aug. 1, 2002, Goddard Space Flight Center.

- NASA's Grace Finds Greenland Melting Faster, 'Sees' Sumatra Quake, December 20, 2005, Goddard Space Flight Center.

- "WGS84RPT.tif:Corel PHOTO-PAINT" (PDF). Retrieved 2018-10-17.

- "Info" (PDF). earth-info.nga.mil. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2020-08-04. Retrieved 2008-12-31.

- "Equatorial Radius of the Earth". Numerical Standards for Fundamental Astronomy: Astronomical Constants : Current Best Estimates (CBEs). IAU Division I Working Group. 2012. Archived from the original on 2016-08-26. Retrieved 2016-08-10.

- Christopher Jekeli (2016). Geometric Reference Systems in Geodesy (PDF). Ohio State University, Columbus, Ohio. Retrieved 13 May 2023.

- Bowring, B. R. (October 1987). "Notes on the curvature in the prime vertical section". Survey Review. 29 (226): 195–196. doi:10.1179/sre.1987.29.226.195.

- Bomford, G. (1952). Geodesy. OCLC 489193198.

- Christopher Jekeli (2016). Geometric Reference Systems in Geodesy (PDF). Ohio State University, Columbus, Ohio. Retrieved 13 May 2023.

- Lass, Harry (1950). Vector and Tensor Analysis. McGraw Hill Book Company, Inc. pp. 71–77. ISBN 9780070365209.

- Torge, Wolfgang (2001). Geodesy. ISBN 9783110170726.

- Moritz, H. (March 2000). "Geodetic Reference System 1980". Journal of Geodesy. 74 (1): 128–133. Bibcode:2000JGeod..74..128.. doi:10.1007/s001900050278. S2CID 195290884.

- Snyder, J.P. (1987). Map Projections – A Working Manual (US Geological Survey Professional Paper 1395) p. 16–17. Washington D.C: United States Government Printing Office.

- "Discover-TheWorld.com – Guam – POINTS OF INTEREST – Don't Miss – Mariana Trench". Guam.discover-theworld.com. 1960-01-23. Archived from the original on 2012-09-10. Retrieved 2013-09-16.

- Frédéric Chambat; Bernard Valette (2001). "Mean radius, mass, and inertia for reference Earth models" (PDF). Physics of the Earth and Planetary Interiors. 124 (3–4): 234–253. Bibcode:2001PEPI..124..237C. doi:10.1016/S0031-9201(01)00200-X. Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 July 2020. Retrieved 18 November 2017.

- Williams, David R. (2004-09-01), Earth Fact Sheet, NASA, retrieved 2007-03-17

- Phillips, Warren (2004). Mechanics of Flight. John Wiley & Sons, Inc. p. 923. ISBN 0471334588.

- Aristotle. On the Heavens. Vol. Book II 298 B. Retrieved 5 November 2017.

- Drummond, William (1817). "On the Science of the Egyptians and Chaldeans, Part I". The Classical Journal. 16: 159.

- Clarke, Alexander Ross; Helmert, Friedrich Robert (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 8 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 801–813.

- "Eratosthenes, the Greek Scientist". Britannica.com. 2016.

- Posidonius, fragment 202

- Cleomedes (in Fragment 202) stated that if the distance is measured by some other number the result will be different, and using 3,750 instead of 5,000 produces this estimation: 3,750 x 48 = 180,000; see Fischer I., (1975), Another Look at Eratosthenes' and Posidonius' Determinations of the Earth's Circumference, Ql. J. of the Royal Astron. Soc., Vol. 16, p. 152.

- Thurston, Hugh (1994). Early astronomy. New York: Springer-Verlag New York. p. 138. ISBN 0-387-94107-X.

- "Almagest – Ptolemy (Elizabeth)". projects.iq.harvard.edu. Retrieved 2022-11-05.

- John Freely, Before Galileo: The Birth of Modern Science in Medieval Europe (2013), ISBN 978-1468308501

- Nancy Smiler Levinson (2001). Magellan and the First Voyage Around the World. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. ISBN 978-0-395-98773-5. Retrieved 31 July 2010.

- Cassini, Jacques (1738). Méthode de déterminer si la terre est sphérique ou non (in French).

- Levallois, Jean-Jacques (1986). "La Vie des sciences". Gallica. pp. 277–284, 288. Retrieved 2019-05-22.

External links

- Merrifield, Michael R. (2010). " The Earth's Radius (and exoplanets)". Sixty Symbols. Brady Haran for the University of Nottingham.