Political systems of the Ashanti Empire

The political organization of the historical Ashanti Empire was characterized by stools which denoted "offices" that were associated with a particular authority. The Golden Stool was the most powerful of all, because it was the office of the King of the Ashanti Empire. Scholars such as Jan Vansina have described the governance of the Ashanti Empire as a federation where state affairs were regulated by a council of elders headed by the king, who was simply primus inter pares.[1]

Structure and organization

In all, the Ashanti state was a centralized state made up of a hierarchy of heads starting from the "Abusua Panyin" who was head of a family or lineage. The family was the basic political unit in the empire. The family or lineage followed the village organization which was headed by the Odikro. All villages were then grouped together to form divisions headed by a divisional head called Ohene. The various divisions were politically grouped to form a state which was headed by an Omanhene or Amanhene. Finally, all Ashanti states formed the Ashanti Empire with the Asantehene as their king.[2] The Seventy-Seven Laws of Komfo Anokye, drafted by Okomfo Anokye, served as the codified constitution of the Ashanti Empire.[3][4][5][6]

The Golden Stool

The Golden Stool was the most powerful of all stools or "offices" in the Ashanti Empire. It was occupied by the Asantehene (King). According to Ashanti oral tradition, the Golden Stool first appeared near the end of the 17th century. It became the spiritual centre of the Empire after King Osei Tutu unified the Ashanti city-states into one empire. According to oral tradition, Okomfo Anokye, the chief priest and adviser of Osei Tutu, brought down the stool from the sky to the earth. He demanded that all chiefs of the Ashanti city-state surrender their stools and recognize the supremacy of the Golden Stool.[6]

Asantemanhyiamu/Kotoko council

The Asantemanhyiamu was a council made up of the Amanhene, Kumasi chiefs and provincial rulers which met once a year.[7] The Asantemanhyiamu translates as a "Great Council"[7] or "National Assembly."[8][9] Some scholars have suggested that the Asantemanhyiamu and the Kotoko council were the same or a similar institution.[7][10] The Asantemanhyiamu served as the judicial and legislative body of the state.[11]

Inner/Kumasi council

As a result of the tedious work faced by the Asantemanhyiamu, another council headed by the king, known as the Inner or Kumasi council was formed in the eighteenth century. This Inner council gradually assumed the administrative duties of the Asantemanhyiamu in the nineteenth century.[12][8][7] This led to the emergence of conflict between the Asantemanhyiamu and the Inner council.[7] Edgerton refers to the Inner council as the Kotoko council instead[13] whiles Wilks writes that the Inner council eventually evolved to be known as the Kumasi council by the 19th century[8][14] The Inner/Kumasi council met everyday in the 19th century sometimes with meetings held until late night under torchlight. The council served as a court of law, justice and legislation.[13][14] The council also held its meetings at the Pramakeseso.[14]

Political factions

During the nineteenth century, there existed two factions that dominated the political scene of Ashanti which are referred to as the Peace party and Imperial/War party by modern historians. Vandervort comments that the Peace party advocated for mercantile policies, free enterprise and it undervalued the importance of military. The Imperial or War party, according to Vandervort, emphasized on state monopoly of trade as well as the support of a strong military force to preserve the empire and intimidate Ashanti neighbors.[15] Throughout the first half of the 19th century, the Peace Party dominated Ashanti politics.[15][16] During this period there emerged a phase termed to be similar to a capitalist revolution by Vandervort, which saw the growth in trade of kola nuts, gold, palm oil and strengthened the position of merchants who made up the Peace party.[15] The Imperial party surpassed the Peace party as the major influence in Ashanti politics starting in the 1870s following the dip in relations with the British Empire.[15]

Mpanyimfo

The Mpanyimfo in Ashanti was an assembly of the oldest members of a particular territory, who represented the inhabitants and acted as advisors to the chief in administrative matters.[17]: 77

Executive

Asantehene

The Ashanti Empire was made up of a number of states grouped together and headed by a monarch. The Asantehene was regarded as primus inter pares.[18] Thus, he was the highest form of authority in the empire and he held more power than the paramount chiefs known as the Amanhene, who were leaders of Ashanti states such as Mampong, Kokufu, Ejisu, Juaben and Bekwai. But the Asantehene did not enjoy absolute royal rule; several checks curbed any abuse of power. All Ashanti authorities including the Asantehene, pledged allegiance to the Golden stool.[18][19][20] The Asantehene was the chief judge, chief administrator and commander-in-chief of the Ashanti army.[2]

Amanhene

The Ashanti Empire was made up of metropolitan and provincial states. The metropolitan states were made up of Ashanti citizens known as amanfo. The provincial states were other kingdoms absorbed into the empire. Every metropolitan Ashanti state was headed by the Amanhene or paramount chief. Each of these paramount chiefs served as principal rulers of their own states, where they exerted executive, legislative and judicial powers.[18]

Ohene

The Ohene were divisional chiefs under the Amanhene. Their major function was to advise the Amanhene. The divisional chiefs were the highest order in various Ashanti state divisions. The divisions were made up of various villages put together. Examples of divisional chiefs included Krontihene, Nifahene, Benkumhene, Adontenhene and Kyidomhene.[18]

Odikuro

Each village in Asante had a chief called Odikro who was the owner of the village. The Odikro was responsible for the maintenance of law and order. He also served as a medium between the people of his jurisdiction, the ancestor and the gods. As the head of the village, the Odikro presided over the village council.[18][2]

Queen

.jpg.webp)

The queen or Ohenemaa was an important figure in Ashanti political systems. She was the most powerful female in the Empire. She had the prerogative of being consulted in the process of installing a chief or the king, as she played a major role in the nomination and selection. She settled disputes involving women and was involved in decision-making alongside the Council of elders and chiefs.[18] Not only did she participate in the judicial and legislative processes, but also in the making and unmaking of war, and the distribution of land.[21]

Osei Kwadwo reforms

The offices of government and public administration in Asante were completely reorganized during the reign of Asantehene Osei Kwadwo (r. 1764–1777) in a major administrative reform. He began a meritocratic system of appointing central officials according to their ability, rather than their birth.[22] A group classification emerged in Ashanti politics.

Adehyedwa stools

The Adehyedwa stools were offices originally independent of the king, that is, they were either pre-Ashanti stools that had been incorporated into the Ashanti administration system after the establishment of the kingdom, or they were non-Ashanti stools that took over into the Ashanti administrative system due to special fidelity and loyalty. The succession in office was mostly regulated by maternal law with the exception of the Asafo stool in Kumasi. Matriclan succession meant that the successor for the office of an Adehyedwa chair was determined through the election of a noble who was suitable for the office within the maternal consanguinity.

Poduodwa stools

The Poduodwa stools were offices created by the king and inherited by a certain lineage. This included the Bantama stool in Kumasi (Bantamahene or Bantahene). Bantama was the location of the mausoleum of the royal family. The bantahene was the chief, authority over the mausoleum however was traditionally exercised by the Asante Krontihene (Minister of Defence).

Esomdwa stools (including the Mmammadwa stools)

The Esomdwa stools were offices of public administration ("Esom") that do not form part of the Adehyewa and Poduodwa stools. Among them were the Mmammadwa stools whose succession was organized via the “Fekuw” system. The Fekuw system was a kinship relationships that arose from the paternal blood line. However, the king had the right to intervene in the succession and to appoint a successor himself.

All office holders of a stool of the three categories mentioned had to swear allegiance to the king. These “stools” (offices) were subordinate to the highest of all stools, the golden stool, occupied by the Asantehene. They were therefore strictly separated from the group of Abusuadwa stools, which were not subject to the Golden stool.

The chiefs of the regional and supraregional public administration had the Ahenfie which served as the local palace police, at their disposal to exercise the state executive power.

Abusuadwa stools

The Abusuadwa stools were all offices within a family clan (defined by the maternal blood line), which did not fulfill any public function and whose function, occupation and succession are solely the matter of their respective matrilineal Abusua. An example is the Oyokohene, head of the Oyoko clan.

With the Kwadwo's administrative reform, among other things, the Asokwafo, previously a troop of royal hornblowers, was transformed into a kind of "personnel pool" for the education and training of future government officials. The king then recruited his officials from the Asokwafo community for a wide variety of administrative tasks. The head of the Asokwafo was the Batahene, who was also responsible for the management of the state trade organizations in Ashanti. The post of Okyeame (spokesman for the king), newly created under Kwadwo, was for example, filled with people from the Asokwafo circle. Likewise, the liaison men to the Europeans during Osai Bonsu's reign had previously been members of the Asokwafo.

Financial administration

The Gyaasehene was the head of the national treasurer's office at the court of the Asantehene.[23][24] He was responsible for the implementation of a general financial budget and expenditure control of the Ashanti Empire. In addition, the Gyaasehene presided over the tax court. Subordinate to him were the Sanaahene, who was responsible for the routine administration of the Adaka Kesie, that is, through which all payments with gold dust from the royal treasury were processed.[25] Every sub Ashanti chief possessed their own local treasury which was managed by a Sanaahene.[26] Subordinate to the Sanaahene (and thus also to the Gyaasehene) was the Fotosanahene, who was head of the cashiers and weighers.[25] The national treasury contained separate offices for the mint (ebura) and the handling of monies (damponkese).[27] According to Wilks, over a hundred workforce known as Buramfo, was employed by the mint in reducing ingots and nuggets to gold dust. The Buramfo workforce was headed by the Adwomfohene who presided over the guild of goldsmiths.[28] The arm responsible for revenue collection was the Atogye. Members of this institution travelled to the villages, towns and cities of the empire to collect taxes, tributes and tolls.[29]

Military administration

Among the Akan of the Gold Coast, Krontihene (or Kontihene) is the title of "leader of the warriors", who was sometimes also referred to as Sahene (war leader). He embodied the Minister of War of the Ashanti Empire and the Commander-in-Chief of the Ashanti Army in the absence of the King.[30] Edgerton relates the process to justify war in Ashanti with that of the United States Congress. Although the Asantehene was commander in chief of the army, the decision to go to war fell to the function of the National Assembly and Inner Council.[31]

Bureaucracy

Wilks states that the empire was bureaucratic as early as the 18th century due to reforms by the Ashanti kings. The Ashanti king appointed officers based on merit and assigned specific duties in the administration. All chiefs had the authority to appoint and dismiss staff. They also had the power to create a new office or abolish old ones.[32]

Diplomacy

Historian Adjaye identifies three types of professional Ambassadors in Ashanti. He lists the Ambassador-at-large, roving ambassadors and resident ambassadors. Roving ambassadors like Oheneba Owusu Dome, traveled from place to place for political purposes. In addition, there were temporal or Ad hoc ambassadors whose appointment came to an end following the conclusion of their missions.[33] Training was mainly obtained through apprenticeship as young men observed the professionals in court for experience. Qualification was based on merit.[33] Diplomatic missions were carried out mainly through oral or unwritten means. Despite the Ashanti being pre-literate, the Ashanti chancery did employ writing to an extent from the nineteenth century, as a solution to the weakness of oral diplomatic communication. Literate members of the chancery were educated by the British for instance. Adjaye estimates that Ashanti's diplomatic documents "could have exceeded several thousands" based on the remains of Ashanti letters found today in archival centers in Ghana, the United Kingdom, the Hague, Denmark, and Switzerland.[33]

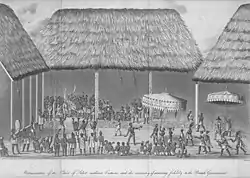

The Ashanti chancery was made up of four district bureaus. They included the Dutch bureau which was responsible for maintaining relations with the Dutch, the Danish bureau responsible for Danish and southeastern Gold Coast affairs, the Arabic bureau which directed communication with Muslim states in Northern Ghana and the English bureau which was in charge of Ashanti affairs with the British and Fante on the coast.[33] Foreign envoys particularly from the coast were stopped at the southern borders of Ashanti until the Asantehene was prepared to receive them. This period of waiting could last from a day or two or even several weeks. After being allowed into Ashanti, the envoy had to wait until a date was fixed for his reception in the capital. When the foreign envoy was allowed into Kumasi, they were welcomed with large ceremonies. Throughout their stay in Kumasi, the envoys were provided with free accommodation as well as allowances on food and drink from the Ashanti government.[34]

Okyeame (Linguist)

From Eisendstadt's work, the Okyeame is defined as the chief linguist who performed roles similar to that of a prime minister.[27] Each town, district or region of Ashanti had an okyeame as a representative in the council. Adjaye also states that the collectively, the Akyeame (plural) performed both bureaucratic and judicial functions.The head of all Akyeame was the Akyeamehene who served as a Minister of Foreign Affairs and Chief of protocol.[33]

Other personnel

The Nhenkwaa were a corps of envoys who served the Asantehene and all principal chiefs. By the 19th century, members of the Nhenkwaa were involved in the diplomatic structure of Ashanti. Unlike the Okyeame who was employed on embassies to more distant towns and foreign states, the Nhenkwaa were mostly sent on missions around Metropolitan Ashanti.[33] The Afenasoafo grew to prominence starting from the early 19th century when they were employed as officials to dispatch messages between Ashanti and foreign governments. Besides their major function as transmitters of messages, the Afenasoafo engaged in the negotiation process for peace making or returning fugitives. They also provided the diplomatic channel of communication between foreign envoys and the Asantehene.[33] The Nseniefo, which translates as criers or heralds, enforced law and order at the meetings of the Asantemanhyiamu and whenever the Asantehene sat in session. The Nseniefo publicized all new decrees and regulations throughout the empire. For instance, after the ratification of the Bowdich Treaty of 1817, the Nseniefo traveled to all the principal towns and villages where they assembled the people through the use of gongs for the announcement on the status of the treaty.[33]

Elections and Impeachment

Elections

During the period between the death of an Asantehene and the election of a successor, the Mamponghene, the Asantehene's deputy, acted as a regent.[22] This policy was only changed during a time of civil war in the late 19th century, when the Kwasafomanhyiamu or governing council itself ruled as regent.[22] The succession was decided by a series of councils of Asante nobles and other royal family members.[22] The methods of electing a chief varied from one chiefdom to another. For the election of the Asantehene, the Queen mother nominated eligible males as candidates from a royal lineage. She then consulted the elders of that lineage. The final candidate is then selected. The nomination was sent to a council of elders or kingmakers, who represent other Ashanti states.[35] The Nkwankwaahene who represented the commoners, indicated if there was widespread approval or disapproval of the nominee. If the commoners disapproved of the nominee, the process was restarted. If Chosen, the new King was enstooled by the kingmakers.[36][37]

Impeachment

Kings of the Ashanti Empire who violated any of the oaths taken during his or her enstoolment, were destooled by Kingmakers.[38] For instance, if a king punished citizens arbitrarily or was exposed as corrupt, he would be destooled. Destoolment entailed kingmakers removing the sandals of the king and bumping his buttocks on the ground three times. Once destooled from office, his sanctity and thus reverence were lost, as he could not exercise any of the powers he had as king; this includes Chief administrator, Judge, and Military Commander. The now previous king was dispossessed of the Stool, swords and other regalia which symbolized his office and authority. He also lost his position as custodian of the land. However, even if destooled from office, the king remained a member of the royal family from which he was elected.[38] One impeachment occurred during the reign of Kusi Obodom, caused by a failed invasion of Dahomey.[39]

References

- Vansina (1962), p. 333

- Seth Kordzo Gadzekpo (2005). History of Ghana: Since Pre-history. Excellent Pub. and Print. pp. 91–92. ISBN 9988070810. Retrieved 2020-12-27 – via Books.google.com.

- McCaskie, T.C. (1986). "Komfo Anokye of Asante: Meaning, History and Philosophy in an African Society". The Journal of African History. 27 (2): 315–339. doi:10.1017/S0021853700036690. JSTOR 181138. S2CID 145530470.

- Claessen, Henri J.M.; Oosten, Jarich Gerlof (1996). Ideology and the Formation of Early States. Brill. p. 89. ISBN 9789027979049.

- Irele, Abiola; Jeyufu, Biodun (2010). The Oxford Encyclopedia of African thought, Volume 1. Oxford University Press. p. 299. ISBN 9780195334739.

- P. H. Coetzee (1998). The African Philosophy Reader. Psychology Press. p. 405. ISBN 9780415189057.

- Eisenstadt, Abitbol & Chazan (1988), p. 83

- Ivor Wilks (1989), p. 392–397

- T.C. McCaskie (2003), p. 146

- Ivor Wilks (1989), p. 391

- Obeng (1996), p. 25

- Obeng (1996), p. 26

- Edgerton (2010), p. 32

- Ivor Wilks (1989), p. 403

- Vandervort (2015), p. 86

- Ivor Wilks (1989), p. 83

- Rattray, Robert Sutherland (1929). Ashanti Law and Constitution (PDF). Oxford, Oxfordshire: Clarendon Press. OCLC 921009966. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2 March 2021.

- Prince A. Kuffour (2015). Concise Notes on African and Ghanaian History. K4 Series Investment Ventures. pp. 205–206. ISBN 9789988159306. Retrieved 2020-12-16 – via Books.google.com.

- Tordoff, William (November 1962). "The Ashanti Confederacy1". The Journal of African History. 3 (3): 399–417. doi:10.1017/S0021853700003327. ISSN 1469-5138. S2CID 159479224.

- Aidoo, Agnes A. (1977). "Order and Conflict in the Asante Empire: A Study in Interest Group Relations". African Studies Review. 20 (1): 1–36. doi:10.2307/523860. ISSN 0002-0206. JSTOR 523860. S2CID 143436033.

- Arhin, Kwame, "The Political and Military Roles of Akan Women", in Christine Oppong (ed.), Female and Male in West Africa, London: Allen and Unwin, 1983.

- Shillington, History of Africa, p. 195.

- Fage, J.D. and Roland Oliver (1975). The Cambridge History of Africa: From c. 1600 to c. 1790, edited by Richard Gray. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 317. ISBN 0521204135.

- Frank K. Adams (2010), p. 18

- Wilks (1966)

- Afosa, Kwame (1985). "Financial Administration of the ancient Ashanti Empire". The Accounting Historians Journal. 12 (2): 109–115. doi:10.2308/0148-4184.12.2.109. JSTOR 40697868.

- Eisenstadt, Abitbol & Chazan (1988), p. 81

- Ivor Wilks (1989), p. 421

- Ivor Wilks (1989), p. 423

- Frank K. Adams (2010), p. 14

- Edgerton (2010), p. 52

- Frank K. Adams (2010), pp. 13–14

- Adjaye, Joseph K. (1985). "Indigenous African Diplomacy: An Asante Case Study". The International Journal of African Historical Studies. 18 (3): 487–503. doi:10.2307/218650. JSTOR 179951.

- Irwin, Graham W. (1975). "Precolonial African Diplomacy: The Example of Asante". The International Journal of African Historical Studies. 8 (1): 81–96. doi:10.2307/217487. JSTOR 217487.

- Timo Kallinen (2018). Divine Rulers in a Secular State. BoD - Books on Demand. pp. 32–33. ISBN 978-9522226822. Retrieved 2020-12-27 – via Books.google.com.

- Apter David E. (2015). Ghana in Transition. Princeton University Press. p. 112. ISBN 9781400867028.

- Chioma, Unini (2020-03-15). "Historical Reminisciences: Great Empires Of Yore (Part 15) By Mike Ozekhome, SAN". TheNigeriaLawyer. Retrieved 2020-05-30.

- Obeng (1996), p. 31–32

- Pescheux, page 449

Bibliography

- Vansina, Jan (1962). "A Comparison of African Kingdoms". Africa: Journal of the International African Institute. 32 (4): 324–335. doi:10.2307/1157437. JSTOR 1157437. S2CID 143572050.

- Emmanuel Akyeampong, Pashington Obeng: Spirituality, Gender, and Power in Asante History. In: The International Journal of African Historical Studies. 28 (3), 1995, S. 481–508.

- Edgerton, Robert B. (2010). The Fall of the Asante Empire: The Hundred-Year War For Africa's Gold Coast. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 9781451603736.

- Eisenstadt, Shmuel Noah.; Abitbol, Michael; Chazan, Naomi (1988). The Early State in African Perspective: Culture, Power, and Division of Labor. Brill. ISBN 9004083553.

- Ivor Wilks (1989). Asante in the Nineteenth Century: The Structure and Evolution of a Political Order. CUP Archive. ISBN 9780521379946. Retrieved 2020-12-29 – via Books.google.com.

- Wilks, Ivor (1966). "Aspects of Bureaucratization in Ashanti in the Nineteenth Century". The Journal of African History. 7 (2): 215–232. doi:10.1017/S0021853700006289. JSTOR 179951. S2CID 159872590.

- Margaret Priestley: The Ashanti question and the British: eighteenth-century origins. In: Journal of African History. 2 (1), 1961, S. 35–59.

- Obeng, J.Pashington (1996). Asante Catholicism; Religious and Cultural Reproduction among the Akan of Ghana. Vol. 1. Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-10631-4.

- T.C. McCaskie (2003). State and Society in Pre-colonial Asante. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521894326.

- William Tordoff: The Ashanti Confederacy. In: Journal of African History. 3 (3), 1962, S. 399–417.

- John K. Fynn: The reign and times of Kusi Obodum 1750-64. In: Transactions of the Historical Society of Ghana. 8, 1965, S. 24–32.

- Kevin Shillington, 1995 (1989), History of Africa, New York: St. Martin's Press.

- Frank K. Adams (2010). Odwira and the Gospel: A Study of the Asante Odwira Festival and Its Significance for Christianity in Ghana. OCMS. ISBN 9781870345590.

- Pescheux, Gérard (2003). Le royaume asante (Ghana): parenté, pouvoir, histoire, XVIIe-XXe siècles. Paris: KARTHALA Editions. p. 582. ISBN 2-84586-422-1.

- Vandervort, Bruce (2015). Wars Of Imperial Conquest. Routledge. pp. 85–86. ISBN 978-1-13-422374-9.