American paddlefish

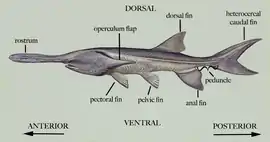

The American paddlefish (Polyodon spathula, also known as a Mississippi paddlefish, spoon-billed cat, or spoonbill) is a species of ray-finned fish. It is the last living species of paddlefish (Polyodontidae). This family is most closely related to the sturgeons; together they make up the order Acipenseriformes, which are one of the most primitive living groups of ray-finned fish. Fossil records of other paddlefish species date back 125 million years to the Early Cretaceous, with records of Polyodon extending back 65 million years to the early Paleocene. The American paddlefish is a smooth-skinned freshwater fish with an almost entirely cartilaginous skeleton and a paddle-shaped rostrum (snout), which extends nearly one-third its body length. It has been referred to as a freshwater shark because of its heterocercal tail or caudal fin resembling that of sharks, though it is not closely related.[7] The American paddlefish is a highly derived fish because it has evolved specialised adaptations such as filter feeding. Its rostrum and cranium are covered with tens of thousands of sensory receptors for locating swarms of zooplankton, its primary food source. The only other species of paddlefish that survived to modern times was the Chinese paddlefish (Psephurus gladius), last sighted in 2003 in the Yangtze River in China and considered to have gone extinct no later than 2010.

| American paddlefish Temporal range: | |

|---|---|

| |

| American paddlefish | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Actinopterygii |

| Order: | Acipenseriformes |

| Family: | Polyodontidae |

| Genus: | Polyodon Lacépède, 1797[3] |

| Species: | P. spathula |

| Binomial name | |

| Polyodon spathula | |

| Synonyms[5][6] | |

|

Genus

Species

| |

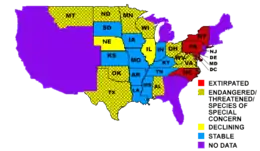

The American paddlefish is native to the Mississippi river basin and once moved freely under the relatively unaltered conditions that existed prior to the early 1900s. It commonly inhabited large, free-flowing rivers, braided channels, backwaters, and oxbow lakes throughout the Mississippi River drainage basin, and adjacent Gulf Coast drainages. Its peripheral range extended into the Great Lakes, with occurrences in Lake Huron and Lake Helen in Canada until about 1917.[8][9] American paddlefish populations have declined dramatically primarily because of overfishing, habitat destruction, and pollution. Poaching has also been a contributing factor to its decline and is liable to continue to be so as long as the demand for caviar remains strong. Naturally occurring American paddlefish populations have been extirpated from most of their peripheral range, as well as from New York, Maryland, Virginia, and Pennsylvania. They have been reintroduced in the Allegheny, Monongahela and Ohio river systems in western Pennsylvania. However, their current range has been reduced to the Mississippi and Missouri River tributaries and Mobile Bay drainage basin. American paddlefish are currently found in twenty-two states in the U.S., and are protected under state, federal and international laws.

Taxonomy, etymology and evolution

In 1797, French naturalist Bernard Germain de Lacépède established the genus Polyodon for paddlefish,[3] which today includes a single extant species, Polyodon spathula. Lacépède disagreed with Pierre Joseph Bonnaterre's description in Tableau encyclopédique et méthodique (1788), which had suggested that paddlefish were a species of shark. When Lacépède established his binomial name Polydon feuille he was unaware the species had already been described in 1792 by taxonomist Johann Julius Walbaum, who had named it as Squalus spathula.[4][10][11] Consequently spathula has priority as the specific name (and 'Walbaum, 1792' is the taxonomic authority to be cited).[12] But Walbaum's generic name Squalus was already in use for dogfish, so Lacépède's Polyodon is the valid name for this paddlefish genus. Hence 'Polyodon spathula (Walbaum, 1792)' is the accepted full scientific name of the American paddlefish.[13]

The American paddlefish is the sole surviving species in the paddlefish family, the Polyodontidae. This is the sister group to the sturgeons (family Acipenseridae); evidence from DNA sequences suggest that their last common ancestor lived roughly 140 million years ago.[14] Together these families compose the Acipenseriformes, an order of basal ray-finned fishes.[15] Paddlefish have a long fossil record dating back to the Early Cretaceous 125 million years ago.[16] American paddlefish are often referred to as primitive fish, or relict species, because of morphological characteristics that they retain from some of their early fossil ancestors.[17] These characteristics include a skeleton composed primarily of cartilage, and a deeply forked heterocercal (spine extending into the upper lobe) caudal fin similar to that of sharks, although they are not closely related.[18]

The family Polyodontidae comprises six known species: three fossil species from western North America, one fossil species from China,[16] one recently extinct species from China (the Chinese paddlefish, Psephurus gladius; last recorded 2003),[19][20] and the single extant species, the American paddlefish, native to the Mississippi River Basin in the United States.[21] DNA sequences suggest the Chinese and American paddlefishes diverged about 68 million years ago.[14] The oldest fossils of paddlefish belonging to Polyodon are those of P. tuberculata from the Lower Paleocene Tullock Member of the Fort Union Formation in Montana, dating to around 65 million years ago.[16][22] An elongated rostrum is a morphological characteristic of Polyodontidae, but only the genus Polyodon has characteristics adapted specifically for filter feeding, including the jaw, gill arches, and cranium. The gill rakers of American paddlefish are composed of extensive comb-like filaments believed to have inspired the etymology of the genus name, Polyodon, a Greek compound word meaning "many toothed". Adult American paddlefish are actually toothless, although numerous small teeth less than 1 mm (0.039 in) were found in a juvenile paddlefish measuring 630 mm (25 in). The name spathula references the elongated, paddle-shaped snout or rostrum.[23][24] Compared to Chinese paddlefish and fossil genera, American paddlefish (and the fossil relative P. tuberculata) are considered to be highly derived because of their specialised adaptations.[25]

Unlike the planktivorous American paddlefish, Chinese paddlefish were strong swimmers, grew larger, and were opportunistic piscivores that fed on small fishes and crustaceans. Some distinct morphological differences of Chinese paddlefish include a narrower, sword-like rostrum, and a protrusible mouth. They also had fewer, thicker gill rakers than American paddlefish.[23][24]

Description

American paddlefish are among the largest and longest-lived freshwater fishes in North America.[26] They have a shark-like body, average 1.5 m (4.9 ft) in length, weigh 27 kg (60 lb), and can live in excess of thirty years.[27] For most populations the median age is five to eight years and the maximum age is fourteen to eighteen years.[26] The age of American paddlefish is best determined by dentary studies, a process which usually occurs on fish harvested during snagging season, a popular sport fishing activity in certain parts of the U.S. The dentary is removed from the lower jawbone, cleaned of any remaining soft tissue, and cross-sectioned to expose the annual rings. The dentary rings are counted in much the same way a tree is aged. Dentary studies suggest that some individuals can live 60 years or longer, and that females typically live longer and grow larger than males.[28]

American paddlefish are smooth-skinned and almost entirely cartilaginous. Their eyes are small and directed laterally. They have a large, tapering operculum flap, a large mouth, and a flat, paddle-shaped rostrum that measures approximately one-third of their body length. During the initial stages of development from embryo to hatchling, American paddlefish have no rostrum. It begins to form shortly after hatching.[29][30] The rostrum is an extension of the cranium, not of the upper and lower jaws or olfactory system as with the long snouts of other fish.[25][26] Other distinguishing characteristics include a deeply forked heterocercal caudal fin and dull coloration, often with mottling, ranging from bluish gray to black dorsally grading to a whitish underbelly.[24]

Feeding ecology and physiology

Scientists began to debate the function of the American paddlefish's rostrum when the species was described in the late 1700s.[31] They had once believed it was used to excavate bottom substrate or functioned as a balancing mechanism and navigational aid.[29] However, laboratory experiments in 1993 that utilized advanced technology in the field of electron microscopy have established conclusively that the rostrum of American paddlefish is covered with tens of thousands of sensory receptors. These receptors are morphologically similar to the ampullae of Lorenzini of sharks and rays, and are indeed passive ampullary-type electroreceptors used by American paddlefish to detect plankton.[31] Clusters of electroreceptors also cover the head and operculum flaps. The diet of the American paddlefish consists primarily of zooplankton. Their electroreceptors can detect weak electrical fields that signal not only the presence of zooplankton, but also the individual feeding and swimming movements of zooplankton appendages.[29] When a swarm of zooplankton is detected, the paddlefish swims forward continuously with its mouth wide open, forcing water over the gill rakers to filter out prey. Such feeding behavior is considered ram suspension-feeding. Further research has indicated that the electroreceptor of the paddlefish may serve as a navigational aid for obstacle avoidance.[31][29]

American paddlefish have small undeveloped eyes that are directed laterally. Unlike most fishes, American paddlefish hardly respond to overhead shadows or changes in illumination. Electroreception appears to have largely replaced vision as a primary sensory modality, which indicates a reliance on electroreceptors for detecting prey.[31][29] However, the rostrum is not their only means of food detection. Some reports suggest a damaged rostrum would render American paddlefish less capable of foraging efficiently to maintain good health, but laboratory experiments and field research indicate otherwise.[25][29] As well as electroreceptors on the rostrum, American paddlefish have sensory pores covering nearly half of the skin surface extending from the rostrum to the top of the head down to the tips of the operculum flaps. Studies have indicated that American paddlefish with damaged or abbreviated rostrums are still able to forage and maintain good health.[25][29]

Reproduction and life cycle

American paddlefish are long-lived, sexually late maturing pelagic fish. Females do not begin spawning until they are seven to ten years old, some as late as sixteen to eighteen years old. Females do not spawn every year; rather they spawn every second or third year. Males spawn more frequently, usually every year or every other year beginning around age seven, some as late as nine or ten years of age.[29][32]

American paddlefish begin their upstream spawning migration sometime during early spring; some begin in late fall.[32] They spawn on silt-free gravel bars that would otherwise be exposed to air or covered by very shallow water were it not for the rises in the river from snow melt and annual spring rains that cause flooding.[33] Although availability of preferred spawning habitat is essential, there are three precise environmental events that must occur before American paddlefish will spawn.[34][29] The water temperature must be from 55 to 60 °F (13 to 16 °C); the lengthened photoperiod which occurs in spring triggers biological and behavioral processes that are dependent on increasing day length; and there must be a proper rise and flow in the river before a successful spawn can occur. Historically, American paddlefish did not spawn every year because the precise environmental events occurred just once every 4 or 5 years.[34]

American paddlefish are broadcast spawners, also referred to as mass spawners or synchronous spawners. Gravid females release their eggs into the water over bare rocks or gravel at the same time males release their sperm. Fertilization occurs externally. The eggs become sticky after they are released into the water and will attach to the bottom substrate. Incubation varies depending on water temperature, but in 60 °F (16 °C) water the eggs will hatch into larval fish in about seven days.[32] After hatching, the larval fish drift downstream into areas of low flow velocity where they forage on zooplankton.[32]

Young American paddlefish are poor swimmers which makes them susceptible to predation. Therefore, rapid first-year growth is important to their survival.[32] Fry can grow about 1 in (2.5 cm) per week,[35] and by late July the fingerlings are around 5–6 in (13–15 cm) long.[32] Their rate of growth is variable and highly dependent on food abundance. Higher growth rates occur in areas where food is not limited. The feeding behavior of fingerlings is quite different from that of older juveniles and adults. They capture individual plankton one by one, which requires detection and location of individual Daphnia on approach, followed by an intercept maneuver to capture the selected prey.[31] By late September fingerlings have developed into juveniles, and are around 10–12 in (25–30 cm) long. After the 1st year their growth rate slows and is highly variable. Studies indicate that by age 5 their growth rate averages around 2 in (5.1 cm) per year depending on the abundance of food and other environmental influences.[24]

Habitat and distribution

American paddlefish are highly mobile and well adapted to living in rivers.[18] They inhabit many types of riverine habitats throughout much of the Mississippi Valley and adjacent Gulf slope drainages. They occur most frequently in deeper, low current areas such as side channels, oxbows, backwater lakes, bayous, and tailwaters below dams. They have been observed to move more than 2,000 mi (3,200 km) in a river system.[18]

American paddlefish are endemic to the Mississippi River Basin, historically occurring from the Missouri and Yellowstone rivers in the northwest to the Ohio and Allegheny rivers of the northeast; the headwaters of the Mississippi River south to its mouth, from the San Jacinto River in the southwest to the Tombigbee and Alabama rivers of the southeast.[26] They were extirpated from New York, Maryland and Pennsylvania, as well as from much of their peripheral range in the Great Lakes region, including Lake Huron and Lake Helen in Canada.[36][34] In 1991, Pennsylvania implemented a reintroduction program utilizing hatchery-reared American paddlefish in an effort to establish self-sustaining populations in the upper Ohio and lower Allegheny rivers. In 1998, New York initiated a stocking program upstream in the Allegheny Reservoir above Kinzua Dam, and a second stocking in 2006 in Conewango Creek, a relatively unaltered section of their historic range. Reports of free ranging adults captured by gill nets have since been documented in Pennsylvania and New York, but there is no evidence of natural reproduction.[37][38] They are currently found in 22 states in the US, and are protected under state and federal laws. There are 13 states that allow commercial or sport fishing for American paddlefish.[29]

Human interaction

Propagation and culture

The artificial propagation of American paddlefish began with the efforts of the Missouri Department of Conservation during the early 1960s, and focused primarily on maintenance of the sport fishery.[39] However, it was the growing importance of American paddlefish for their meat and roe that became the catalyst for further development of culture techniques for aquaculture in the United States.[39] Artificial propagation requires broodstock which, because of the late sexual maturation of American paddlefish, are initially obtained from the wild and brought into a hatchery environment.[40] The fish are injected with LH-RH hormone to stimulate spawning. The number of eggs a female may produce depends on the size of the fish and can range anywhere from 70,000 to 300,000 eggs. Unlike most teleosts, the oviduct branches of American paddlefish and sturgeons are not directly attached to the ovaries; rather, they open dorsally into the body cavity. To determine the status of progression toward maturation, ova staging is performed. The process begins with a minor procedure that involves a small abdominal incision from which to extract a few sample oocytes. The oocytes are boiled in water for a few minutes until the yolk is hardened, and then they are cut in half to expose the nucleus. The exposed nucleus is examined under a microscope to determine stage of maturity.[39]

Once maturation is confirmed, one of three procedures is used to extract the eggs from a female paddlefish. The three procedures are:

- the traditional hand-stripping method, considered to be time-consuming and laborious;

- Caesarean section, a relatively quick surgical method of extracting eggs through a 4 in (10 cm) abdominal incision which, though considered faster than hand stripping, can involve time-consuming suturing and an incision resulting in muscular stress and poor suture retention which lowers survival rate; and;

- MIST (minimally invasive surgical technique), which is the fastest of the three procedures because it requires less handling of the fish and eliminates the need for suturing. A small internal incision is made in the dorsal area of the oviduct, which allows direct stripping of eggs from the body cavity through the gonopore bypassing the oviductal funnels.[41][42]

A spermiating male indicates successful production of mature spermatozoa which results in the release of large volumes of milt over the course of three to four days. Milt is collected by inserting a short plastic tube with syringe attached into the urogenital opening of the male and applying light suction with the syringe to draw the milt. The collected milt is diluted in water just prior to adding it to the eggs and the combination is gently stirred for about a minute to achieve fertilization. Fertilized eggs are adhesive and demersal, therefore if incubation is to take place in a flow-through hatching jar, the eggs must be treated to prevent clumping. Incubation usually takes anywhere from five to twelve days.[39]

Hybridization

A 2020 paper reported that eggs from three Russian sturgeons were crossbred with American paddlefish using sperm from four male paddlefish, resulting in hybrids called sturddlefish, a blend of the two names. The offspring had a survival rate of 62–74% and on average reached 1 kg (2.2 lb) after a year of growth. This was the first time such fish from different families were successfully crossbred.[43] Their last common ancestor is estimated to have lived 140 million years ago.[14]

Global commercial market

Advancements in biotechnology have created a global commercial market for the polyculture of American paddlefish. In 1970, American paddlefish were stocked in several rivers in Europe and Asia. Introduction began when five thousand hatched larvae from Missouri hatcheries in the United States were exported to the former Soviet Union for aquacultural utilization.[44] Reproduction was successful in 1988 and 1989, and resulted in the exportation of juveniles to Romania and Hungary. American paddlefish are now being raised in Ukraine, Germany, Austria, the Czech Republic, and the Plovdiv and Vidin regions in Bulgaria. In May 2006, specimens of different sizes and weights were caught by professional fisherman near Prahovo in the Serbian part of the Danube River.[44]

In 1988, fertilized American paddlefish eggs and larvae from Missouri hatcheries were first introduced into China.[44] Since that time, China imports approximately 4.5 million fertilized eggs and larvae every year from hatcheries in Russia and the United States. Some American paddlefish are polycultured in carp ponds and sold to restaurants while others are cultured for brood stock and caviar production. China has also exported American paddlefish to Cuba, where they are farmed for caviar production.[45]

Sport fishing

American paddlefish are a popular sport fish where their populations are sufficient to allow such activity. Areas where there are no self-sustaining populations rely on state and federal restocking programs to maintain a viable fishery. A 2009 report includes the following states as allowing American paddlefish sport fishing per their respective state and federal regulations: Arkansas, Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Kansas, Kentucky, Mississippi, Missouri, Montana, Nebraska, North Dakota, Oklahoma, South Dakota and Tennessee.[37] Since American paddlefish are filter-feeders, they will not take bait or lures, and must be caught by snagging.[32]

The official state record in Kansas is an American paddlefish snagged in 2004 that weighed 144 lb (65 kg). In Montana, an American paddlefish was snagged in 1973 weighing 142.5 lb (64.6 kg). In North Dakota, one snagged in 2010 weighed 130 lb (59 kg).[32] The largest American paddlefish on record was captured in West Okoboji Lake, Iowa, in 1916 by a spear fisherman; it measured 85 in (2.2 m) and weighed an estimated 198 lb (90 kg).[32][46]

Population declines

Overfishing and habitat destruction

American paddlefish populations have declined dramatically, primarily as a result of overfishing and habitat destruction. In 2004 they were listed as Vulnerable (VU A3de ver 3.1) on the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. They are currently proposed for listing as VU 3de throughout their range as the result of a U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service assessment. The assessment concluded that "an overall population size reduction of at least 30% may occur within the next 10 years or three generations due to actual or potential levels of exploitation and the effects of introduced taxa, pollutants, competitors or parasites."[1] American paddlefish are filter-feeding pelagic fish that require large, free-flowing rivers with braided channels, backwater areas, oxbow lakes that are rich in zooplankton, and gravel bars for spawning.[33] Series of dams on rivers such as those constructed on the Missouri River have impounded large populations of American paddlefish, and blocked their upstream migration to spawning shoals.[33] Channelization and groynes or wing dykes have caused the narrowing of rivers and altered flow, destroying crucial spawning and nursery habitat.[34][26][37] As a result, most impounded populations are not self-sustaining and must be stocked to maintain a viable sport fishery.[33]

Zebra mussels

Zebra mussel infestations in the Mississippi River, Great Lakes and other Midwest rivers are also negatively affecting American paddlefish populations. Zebra mussels are an invasive species well adapted for explosive population growth as a result of high rates of fecundity and recruitment. As filter feeders, zebra mussels rely on plankton and can filter significant amounts of phytoplankton and zooplankton from the water, altering the availability of an important food source for paddlefish and native unionidae.[34][47] A few days after the fertilization of zebra mussel eggs, a microscopic larva emerges called a veliger. During this initial stage of development, which usually lasts a few weeks, veligers are able to swim freely in the water column with other microscopic animals comprising zooplankton. Veligers are poor swimmers, making them susceptible to predation by any animal that feeds on zooplankton.[48] However, natural predation of zebra mussels at any stage of development has not made a significant contribution to the long-term reduction of zebra mussel populations.[49]

Poaching and overexploitation

Poaching has been a contributing factor to declining populations of American paddlefish in the states where they are commercially exploited, particularly while the demand for caviar remains strong.[37] Since the 1980s, a trade embargo on Iran restricted imports of the highly sought after and most expensive beluga caviar from the Caspian Sea, limiting U.S. sources of caviar. The most sought-after caviar is produced by sturgeons in the Northern Caspian Sea, but overfishing and poaching have exhausted the supply. American sturgeon and paddlefish populations were targeted as likely substitutes.[29][50]

The roe of American paddlefish can be processed into caviar similar in taste, color, size and texture to sevruga sturgeon caviar from the Caspian Sea.[34][41] Several cases of mislabeled American paddlefish roe sold as Caspian Sea caviar have been prosecuted by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.[29] State and federal regulations restricting the harvest of American paddlefish populations in the wild, and the illegal trafficking of their roe, are strictly enforced. Related violations such as the illegal transport of American paddlefish roe have resulted in convictions with substantial fines and prison sentences.[51][52] American paddlefish are also protected under Appendix II of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES) meaning international trade in the species (including parts and derivatives) is regulated.[53]

Extinction of Chinese paddlefish

The primary reasons for the decline of the now-extinct Chinese paddlefish are similar to those of American paddlefish, which include overfishing, the construction of dams, and destruction of habitat.[36] The last confirmed sighting of a live Chinese paddlefish was from the Yangtze River on January 24, 2003.[54] From 2006 to 2008, scientists conducted surveys in an effort to locate the fish. They used several boats, deployed 4762 setlines, 111 anchored setlines and 950 drift nets covering 488 km (303 mi) on the upper Yangtze River, most of which lies within the protected area of the Upper Yangtze National Nature Reserve. They did not catch a single fish. They also used hydroacoustic equipment to monitor sounds in the water, but were unable to confirm the presence of paddlefish.[54] The species is believed to have gone extinct before 2005 and no later than 2010.[19] The IUCN assessed the species as extinct in 2019, formally publishing this categorisation in 2022.[55]

References

- Grady, J. (U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service) (2020) [errata version of 2019 assessment]. "Polyodon spathula". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2019: e.T17938A174780447. Retrieved August 17, 2020.

- "Appendices | CITES". cites.org. Retrieved January 14, 2022.

- Lacépède, B.G.E. (1797). "Mémoire sur le polyodon feuille". Bulletin des Sciences, par la Société Philomathique de Paris. 1 (6): 49.

- Walbaum, J.J. (1792). Petri ArPetri Artedi sueci genera Piscium in quibus systema totum ichthyologiae proponitur cum classibus, ordinibus, generum characteribus, specierum diffentiis, observationibus plumiris. Redactis Speciebus 2. Ichthyologiae, III. Grypeswaldiae [Greifswald]: Ant. Ferdin. Rose. p. 522.

- Froese, R.; Pauly, D. (2017). "Polydontidae". FishBase version (02/2017). Archived from the original on August 24, 2017. Retrieved May 18, 2017.

- "Polydontidae" (PDF). Deeplyfish- fishes of the world. Archived (PDF) from the original on August 24, 2017. Retrieved May 18, 2017.

- "Extinct freshwater sharks that spawned in saltwater had been mistaken for separate species". Scientific American. January 16, 2014. Retrieved May 5, 2019.

- "COSEWIC assessment and update status report on the paddlefish Polyodon spathula in Canada" (PDF). Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. April 2008.

- "Aquatic Species at Rick – The Paddlefish". Fisheries and Oceans Canada. June 28, 2010. Archived from the original on August 7, 2014. Retrieved December 10, 2014.

- Daniel McKinley (February 1984). "History of a Neglected Account of the Paddlefish, Polyodon spathula". Copeia. 1984 (1): 201–204. doi:10.2307/1445053. JSTOR 1445053.

- Steven Mims; William L. Shelton (January 2005). Anita Kelly; Jeff Silverstein (eds.). Paddlefish (PDF). pp. 227–249. ISBN 978-1-888569-71-1. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 24, 2015. Retrieved November 9, 2014.

{{cite book}}:|journal=ignored (help) - Polyodon spathula. Encyclopedia of Life. 2013. Archived from the original on December 8, 2015. Retrieved October 15, 2014.

- Fricke, R.; Eschmeyer, W.N.; Van der Laan, R. (2022). Eschmeyer's catalog of fishes: genera, species, references: electronic version. California Academy of Sciences. Retrieved April 24, 2022.

- Peng, Z.; Ludwig, A.; Wang, D.; Diogo, R.; Wei, Q.; He, S. (March 2007). "Age and biogeography of major clades in sturgeons and paddlefishes (Pisces: Acipenseriformes)". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 42 (3): 854–862. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2006.09.008. PMID 17158071.

- Imogen A. Hurley; Rachel Lockridge Mueller; Katherine A. Dunn; Eric J. Schmidt; Matt Friedman; Robert K. Ho; Victoria E. Prince; Ziheng Yang; Mark G. Thomas; Michael I. Coates (February 2007). "A New Time-Scale for Ray-Finned Fish Evolution". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 274 (1609): 489–498. doi:10.1098/rspb.2006.3749. PMC 1766393. PMID 17476768.

- Murray, Alison M.; Brinkman, Donald B.; DeMar, David G.; Wilson, Gregory P. (March 3, 2020). "Paddlefish and sturgeon (Chondrostei: Acipenseriformes: Polyodontidae and Acipenseridae) from lower Paleocene deposits of Montana, U.S.A.". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 40 (2): e1775091. Bibcode:2020JVPal..40E5091M. doi:10.1080/02724634.2020.1775091. S2CID 222213273.

- Susan Post. "Species Spotlight: Paddlefish". Illinois Natural History Survey. University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. Archived from the original on May 29, 2014. Retrieved June 18, 2014.

- Steven Zigler (March 13, 2014). "Paddlefish Study Project". Upper Midwest Environmental Sciences Center, US Geological Survey. Archived from the original on October 6, 2014. Retrieved October 15, 2014.

- Zhang, Hui; Jarić, Ivan; Roberts, David L.; He, Yongfeng; Du, Hao; Wu, Jinming; Wang, Chengyou; Wei, Qiwei (2020). "Extinction of one of the world's largest freshwater fishes: Lessons for conserving the endangered Yangtze fauna". Science of the Total Environment. Elsevier BV. 710: 136242. Bibcode:2020ScTEn.710m6242Z. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.136242. ISSN 0048-9697. PMID 31911255. S2CID 210086307.

- "Study declares ancient Chinese paddlefish extinct". Oceanographic. January 9, 2020. Retrieved April 23, 2022.

- "Polyodon spathula (Walbaum, 1792)". Minnesota Department of Natural Resources. 2014. Archived from the original on October 19, 2014. Retrieved October 14, 2014.

- M.L. Warren; B.M. Burr; J.R. Tomelleri (2014). Freshwater Fishes of North America: Volume 1: Petromyzontidae to Catostomidae. Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 211. ISBN 978-1-4214-1202-3. OCLC 883820201.

- Gene Helfman; Bruce B. Collette; Douglas E. Facey; Brian W. Bowen (April 3, 2009). The Diversity of Fishes: Biology, Evolution, and Ecology. John Wiley & Sons. p. 254. ISBN 978-1-4443-1190-7. Archived from the original on June 17, 2016.

- Carla Hassan-Williams; Timothy H. Bonner (2007). "Polyodon spathula". Fishes of Texas Project and Online Database. Texas National History Collection, a division of Texas Natural Science Center, University of Texas at Austin. Archived from the original on July 26, 2014. Retrieved June 19, 2014.

- Lon A. Wilkens Michael & H. Hofmann (2007). "The paddlefish rostrum as an electrosensory organ: a novel adaptation for plankton feeding". BioScience. 57 (5): 399–407. doi:10.1641/B570505.

- Cecil A. Jennings; Steven J. Zigler (2009). Craig P. Paukert; George D. Scholten (eds.). Distribution, Ecology, and Life History; Biology and Life History of Paddlefish in North America: An Update (PDF). pp. 1–22. ISBN 978-1-934874-12-7. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 14, 2014. Retrieved June 18, 2014.

{{cite book}}:|journal=ignored (help) - "Paddlefish". World Wildlife Federation. Archived from the original on July 23, 2014. Retrieved June 19, 2014.

- D.L. Scarnechhia; Brad Schmitz (2010). "Paddlefish". Species of Concern. Montana Chapter of the American Fisheries Society. Archived from the original on September 24, 2015. Retrieved August 28, 2014.

- "Biology of the Paddlefish" (PDF). Louisiana Marine Education Resources, Classroom Projects. Louisiana State University. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 14, 2014. Retrieved June 9, 2014.

- "Paddlefish Polyodon Spathula" (PDF). U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service. May 16, 2001. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 24, 2015. Retrieved June 20, 2014.

- Alexander B. Neiman; David F. Russell; Xing Pei; Winfried Wojtenek; Jennifer Twitty; Enrico Simonotto; Barbara A. Wettring; Eva Wagner; Lon A. Wilkens; Frank Moss (2000). "Stochastic synchronization of electroreceptors in the paddlefish". International Journal of Bifurcation and Chaos. Ohio University. 10 (11): 2499. Bibcode:2000IJBC...10.2499N. doi:10.1142/S0218127400001717. Archived from the original on September 24, 2015. Retrieved June 20, 2014.

- "Paddlefish Questions and Answers". North Dakota Game and Fish Department. 2012. Archived from the original on June 24, 2015. Retrieved June 9, 2014.

- "Paddlefish, Polyodon spathula". Discover Nature Field Guide. Missouri Department of Conservation. Archived from the original on August 24, 2017. Retrieved June 9, 2014.

- Betty Wills (2004). "Paddlefish". Earthwave Society. Archived from the original on October 6, 2014. Retrieved October 3, 2014.

- Dudley Parr. "Progress with Paddlefish Restoration". Pennsylvania Angler and Boater (January/February 1999). Archived from the original on September 3, 2014. Retrieved August 28, 2014.

- Qiwei, W. (2010). "Psephurus gladius". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2010: e.T18428A8264989. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2010-1.RLTS.T18428A8264989.en. Retrieved November 13, 2021.

- Phillip W. Bettoli; Janice A. Kerns; George D. Scholten (December 2009). Craig P. Paukert; George D. Scholten (eds.). Status of Paddlefish in the United States (PDF). pp. 1–16. ISBN 978-1-934874-12-7. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 23, 2022. Retrieved January 27, 2022.

{{cite book}}:|journal=ignored (help) - David G. Argent; William G. Kimmel; Rick Lorson; Paul McKeown; Doug M. Carlson; Mike Clancy (December 2009). Craig P. Paukert; George D. Scholten (eds.). Paddlefish Restoration to the Upper Ohio and Allegheny River Systems (PDF). pp. 1–13. ISBN 978-1-934874-12-7. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 14, 2014. Retrieved June 20, 2014.

{{cite book}}:|journal=ignored (help) - Steven Mims; William L. Shelton; Richard J. Onders (December 2009). Craig P. Paukert; George D. Scholten (eds.). Propagation and Culture of Paddlefish (PDF). pp. 357–383. ISBN 978-1-934874-12-7. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 14, 2014. Retrieved June 22, 2014.

{{cite book}}:|journal=ignored (help) - "Native Fish in the Classroom". Louisiana Marine Education Resources, Classroom Projects. Louisiana State University. Archived from the original on September 3, 2014. Retrieved June 22, 2014.

- Steven D. Mims; William L. Shelton; Forrest S. Wynne; Richard J. Onders (November 1999). "Production of Paddlefish" (PDF). Texas A&M AgriLife Extension Aquaculture, Fisheries, & Pond Management, Publication 437. Southern Regional Aquaculture Center. pp. 1–5. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 10, 2016. Retrieved June 22, 2014.

- Steven Mims; William L. Shelton; Richard J. Onders; Boris Gomelsky (2004). "Technical Notes: Effectiveness of the Minimally Invasive Surgical Technique (MIST) for Removal of Ovulated Eggs from First-Time and Second-Time MIST-Spawned Paddlefish" (PDF). North American Journal of Aquaculture. 66: 70–72. doi:10.1577/c02-053. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 14, 2014. Retrieved June 22, 2014.

- Káldy, Jenő; Mozsár, Attila; Fazekas, Gyöngyvér; Farkas, Móni; Fazekas, Dorottya Lilla; Fazekas, Georgina Lea; Goda, Katalin; Gyöngy, Zsuzsanna; Kovács, Balázs; Semmens, Kenneth; Bercsényi, Miklós (July 6, 2020). "Hybridization of Russian Sturgeon (Acipenser gueldenstaedtii, Brandt and Ratzeberg, 1833) and American Paddlefish (Polyodon spathula, Walbaum 1792) and Evaluation of Their Progeny". Genes. 11 (7): 753. doi:10.3390/genes11070753. PMC 7397225. PMID 32640744.

- Mirjana Lenhardt; A. Hegediš; B. Mićković; Željka Višnjić Jeftić; Marija Smederevac; I. Jarić; G. Cvijanović; Z. Gačić (2006). "First Record of the North American Paddlefish (Polyodon spathula, Walbaum 1792) in the Serbian Part of the Danube River" (PDF). Archives of Biological Science, Belgrade. 58 (3): 27P, 28P. doi:10.2298/abs060327pl. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 14, 2014. Retrieved June 9, 2014.

- Steven D. Mims (February 2006). "Paddlefish Culture: Development Expanding Beyond U.S., Russia, China" (PDF). Global Aquaculture Advocate: 62–63. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 14, 2014. Retrieved June 10, 2014.

- "Seeking paddlefish on the Missouri : Outdoors". Sioux City Journal. October 11, 2012. Archived from the original on August 24, 2017. Retrieved December 12, 2014.

- National Park Service. "Don't Move a Mussel" (PDF). Missouri National Recreational River Zebra Mussel Bulletin. National Park Service. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 14, 2014. Retrieved June 21, 2014.

- Tiffany Murphy (2008). "Dreissena polymorpha". Animal Diversity Web. University of Michigan. Archived from the original on October 30, 2014. Retrieved October 20, 2014.

- Daniel P. Molloy; Alexander Y. Karatayev; Lyubov E. Burlakova; Dina P. Kurandina; Franck Laruelle (1997). "Natural Enemies of Zebra Mussels – Predators, Parasites, and Ecological Competitors". Reviews in Fisheries Science. 5 (1): 83–84. doi:10.1080/10641269709388593.

- Katherine Cooper (March 30, 2016). "Why the Caviar-Producing American Paddlefish Is a Symbol of Luxury and Scarcity". Eater. Retrieved March 8, 2021.

- Gavin Shire (April 15, 2013). "Seven Men Indicted for Alleged Trafficking of Paddlefish Caviar". U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service. Archived from the original on August 21, 2014. Retrieved June 20, 2014.

- David Harper (October 18, 2013). "Man Gets Prison Term in Paddlefish 'Caviar' Criminal Case". Tulsa World. Archived from the original on September 17, 2015. Retrieved June 20, 2014.

- Richard Simms (July 9, 2009). "Federal Authorities Step in to Protect Paddlefish". The Chattanoogan. Archived from the original on September 17, 2015. Retrieved June 19, 2014.

- Jody Bourton (September 29, 2009). "Giant Fish 'Verges on Extinction'". BBC Earth News. Archived from the original on October 6, 2014. Retrieved October 6, 2014.

- Qiwei, W. (2022). "Psephurus gladius". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2022: e.T18428A146104283. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2022-2.RLTS.T18428A146104283.en. Retrieved July 21, 2022.

External links

- The Paddlefish: An American Treasure – documentary chronicling the biology and life history of paddlefish

- Study: 96 percent of vertebrates descended from common ancestor with 'sixth sense'

.jpg.webp)