Pomacentridae

Pomacentridae is a family of ray-finned fish, comprising the damselfishes and clownfishes. This family were formerly placed in the order Perciformes but are now regarded as being incertae sedis in the subseries Ovalentaria in the clade Percomorpha.[2] They are primarily marine, while a few species inhabit freshwater and brackish environments (e.g., Neopomacentrus aquadulcis, N. taeniurus, Pomacentrus taeniometopon, Stegastes otophorus).[3] They are noted for their hardy constitutions and territoriality. Many are brightly colored, so they are popular in aquaria.

| Clownfish and damselfish | |

|---|---|

| |

| Cocoa damselfish, Stegastes variabilis | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Actinopterygii |

| (unranked): | Ovalentaria |

| Family: | Pomacentridae Bonaparte, 1832[1] |

| Type species | |

| Pomacentrus pavo Bloch, 1787 | |

| Genera | |

|

See text | |

Around 385 species are classified in this family, in about 31 genera. Of these, members of two genera, Amphiprion and Premnas, are commonly called clownfish or anemonefish, while members of other genera (e.g., Pomacentrus) are commonly called damselfish.[4] The members of this family are classified in four subfamilies: Amphiprioninae, Chrominae, Lepidozyginae, and Pomacentrinae.[5]

Etymology

The name of the family is derived from the Greek words; poma roughly translates to the English "cover", referring to the fishes' opercula, and kentron is Greek for sting. The name refers to the serrations found along the margins of the opercular bones in many members of this family.[4]

Distribution and habitat

Pomacentrids are found primarily in tropical seas, with a few species occurring in subtropical waters (e.g., Hypsypops rubicundus). Most species are found on or near coral reefs in the Indo-West Pacific (from East Africa to Polynesia). The area from the Philippines to Australia hosts the greatest concentration of species.[6] The remaining species are found in the Atlantic or eastern Pacific. Some species are native to freshwater or brackish estuarine environments.[3][7]

Most members of the family live in shallow water, from 2 to 15 m (6 ft 7 in to 49 ft 3 in) in depth, although some species (e.g., Chromis abyssus) are found below 100 m (330 ft).[8] Most species are specialists, living in specific parts of the reef, such as sandy lagoons, steep reef slopes, or areas exposed to strong wave action. In general, the coral is used as shelter, and many species can only survive in its presence.[7]

The bottom-dwelling species are territorial, occupying and defending a portion of the reef, often centered on shelter. By keeping away other species of fish, some pomacentrids encourage the growth of thick mats of algae within their territories, leading to the common name farmerfish.[7]

Characteristics

Pomacentrids have an orbiculate to elongated body shape, which is often laterally compressed. They have interrupted or incomplete lateral lines and they usually have a single nostril on each side (some species of Chromis and Dascyllus have two on each side).[6] They have small- to medium-sized ctenoid scales. They have one or two rows of teeth, which may be conical or spatulate.

They display a wide range of colors, predominantly bright shades of yellow, red, orange, and blue, although some are a relatively drab brown, black, or grey. The young are often a different, brighter color than adults.

Pomacentrids are omnivorous or herbivorous, feeding on algae, plankton, and small bottom-dwelling crustaceans, depending on their precise habitats. Only a small number of genera, such as Cheiloprion, eat the coral where they live.[7]

They also engage in symbiotic relationship with cleaner gobies of genus Elacatinus, allowing the gobies to feed on ectoparasites on their bodies.[9]

Lifecycle

Before breeding, the males clear an area of algae and invertebrates to create a nest. They engage in ritualised courtship displays, which may consist of rapid bursts of motion, chasing or nipping females, stationary hovering, or wide extension of their fins. After being attracted to the site, the female lays a string of sticky eggs that attach to the substrate. The male swims behind the female as she lays the eggs, and fertilises them externally. Varying by species, brood sizes range from 50 to 1000 eggs.[7]

The male guards the nest for the two to seven days needed for the eggs to hatch. The transparent larvae are 2 to 4 mm (0.079 to 0.157 in) long. They go through a pelagic stage, which depending on the species, can last as little as a week or more than a month.[10] When they arrive at a suitable environment, the young settle and adopt their juvenile colors.[7]

In captivity, pomacentrids live up to 18 years, but they probably do not live longer than 10 to 12 years in the wild.[7]

Genera

The 5th edition of Fishes of the World recognises 31 genera in three subfamilies in the family Pomacentridae:[2][11][1]

† means extinct

- Subfamily Chrominae Allen, 1975

- Acanthochromis Gill, 1863:

- Altrichthys Allen, 1999

- Azurina D.S. Jordan & McGregor, 1898

- Chromis Cuvier, 1814

- Dascyllus Cuvier, 1829

- Subfamily Lepidozyginae Allen, 1975

- Lepidozygus Günther, 1862

- Subfamily Pomacentrinae Bonaparte, 1831

- Abudefduf Fabricius, 1775

- Amblyglyphidodon Bleeker, 1877

- Amblypomacentrus Bleeker, 1877

- Amphiprion Bloch & Schneider, 1801

- Cheiloprion M.C.W. Weber, 1913

- Chrysiptera Swainson, 1839

- Dischistodus Gill, 1863

- Hemiglyphidodon Bleeker, 1877

- Hypsypops Gill, 1861

- Mecaenichthys Whitley , 1929

- Microspathodon Günther, 1862

- Neoglyphidodon Allen, 1991

- Neopomacentrus Allen, 1975

- Nexilosus Heller & Snodgrass, 1903

- Parma Günther, 1862

- Plectroglyphidodon Fowler & Ball, 1824

- Pomacentrus Lacépède, 1802

- Pomachromis Allen & Randall, 1974

- Premnas Cuvier, 1816

- Pristotis Rüppell, 1838

- Similiparma Hemsley, 1986

- Stegastes Jenyns, 1840

- Teixeirichthys J. L. B. Smith, 1953

- †Palaeopomacentrus Bellwood & Sorbini, 1996 [12]

Other authoritiies recognise 4 subfamilies and classify the family as follows:[11]

- Subfamily Chrominae

- Azurina

- Chromis

- Dascyllus

- Pycnochromis Fowler, 1941

- Subfamily Glyphisodontinae

- Abudefduf

- Subfamily Microspathodontinae

- Hypsypops

- Lepidozygus

- Mecaenichthys

- Microspathodon

- Nexilosus

- Parma (fish)|Parma

- Plectroglyphidodon

- Similiparma

- Stegastes

- Subfamily Pomacentrindeae

- Acanthochromis

- Altrichthys

- Amblyglyphidodon

- Amblypomacentrus

- Clownfish|Amphiprion

- Cheiloprion

- Chrysiptera

- Dischistodus

- Hemiglyphidodon

- Neoglyphidodon

- Neopomacentrus

- Pomacentrus

- Pomachromis

- Premnas

- Pristotis

- Teixeirichthys

- †Palaeopomacentrus

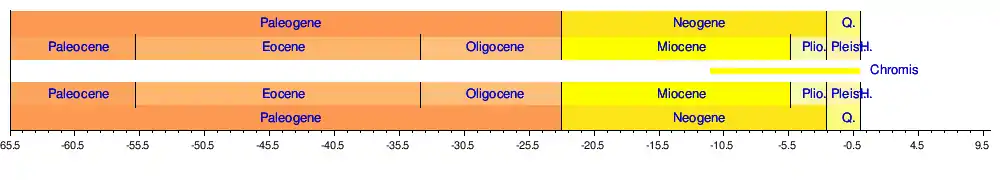

Timeline

References

- Richard van der Laan; William N. Eschmeyer & Ronald Fricke (2014). "Family-group names of Recent fishes". Zootaxa. 3882 (2): 001–230. doi:10.11646/zootaxa.3882.1.1. PMID 25543675.

- J. S. Nelson; T. C. Grande; M. V. H. Wilson (2016). Fishes of the World (5th ed.). Wiley. p. 752. ISBN 978-1-118-34233-6.

- Jenkins, A.P. & G.R. Allen (2002). "Neopomacentrus aquadulcis, a new species of damselfish (Pomacentridae) from eastern Papua New Guinea". Records of the Western Australian Museum. 20: 379–382.

- Froese, Rainer, and Daniel Pauly, eds. (2007). "Pomacentridae" in FishBase. July 2007 version.

- Allen, G.R. (1975). Damselfishes of the South Seas. Neptune City, NJ: T.F.H. Publications. ISBN 978-0-87666-034-8.

- Nelson, J.S. (2006). Fishes of the World. Hoboken: John Wiley and Sons. ISBN 978-0-471-25031-9.

- Allen, Gerald R. (1998). Paxton, J.R.; Eschmeyer, W.N. (eds.). Encyclopedia of Fishes. San Diego: Academic Press. pp. 205–208. ISBN 978-0-12-547665-2.

- Pyle, R.L., J.L. Earle & B.D. Greene (2008). "Five new species of the damselfish genus Chromis (Perciformes: Labroidei: Pomacentridae) from deep coral reefs in the tropical western Pacific". Zootaxa. 1671: 3–31. doi:10.11646/zootaxa.1671.1.2.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Ivan Sazima; Cristina Sazima; Ronaldo B. Francini-Filho; Rodrigo L. Moura (September 2000). "Daily cleaning activity and diversity of clients of the barber goby, Elacatinus figaro, on rocky reefs in southeastern Brazil". Environmental Biology of Fishes. 59 (1): 69–77. doi:10.1023/a:1007655819374. S2CID 24134075.

- Thresher, R.E.; Colin, P.L.; Bell, L.J. (1989). "Planktonic duration, distribution and population structure of western and central Pacific damselfishes (Pomacentridae)". Copeia. 1989 (2): 420–434. doi:10.2307/1445439. JSTOR 1445439.

- Eschmeyer, William N.; Fricke, Ron & van der Laan, Richard (eds.). "Genera in the family Pomacentridae". Catalog of Fishes. California Academy of Sciences. Retrieved 2 October 2022.

- D. R. Bellwood and L. Sorbini (1996). "A review of the fossil record of the Pomacentridae (Teleostei: Labroidei) with a description of a new genus and species from the Eocene of Monte Bolca, Italy". Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. 117 (2): 159–174. doi:10.1111/j.1096-3642.1996.tb02154.x. S2CID 84430386.

External links

- Froese, Rainer, and Daniel Pauly, eds. (2007). "Pomacentridae" in FishBase. January 2007 version.

- Smith, J.L.B. 1960. Coral fishes of the family Pomacentridae from the Western Indian Ocean and the Red Sea. Ichthyological Bulletin; No. 19. Department of Ichthyology, Rhodes University, Grahamstown, South Africa.

- Species inventory of Pomacentridae from New Caledonia.

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)