Poplar Town Hall

Poplar Town Hall is a municipal building at the corner of Bow Road and Fairfield Road in Poplar, London. It is a Grade II listed building.[1]

| Poplar Town Hall | |

|---|---|

The new Poplar Town Hall (2007) | |

| Location | Bow Road, Poplar |

| Coordinates | 51.5284°N 0.0198°W |

| Built | 1938 |

| Architect | Culpin and Son |

| Architectural style(s) | Modernist style |

Listed Building – Grade II | |

| Designated | 24 February 2009 |

| Reference no. | 1393151 |

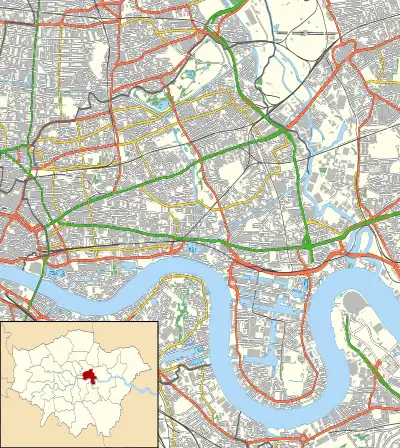

Shown in Tower Hamlets | |

History

The building was commissioned to replace an aging municipal building, still located 1.7 miles (2.7 km) due south on Poplar High Street, with a distinctive octagonal tower and dome and mosaic detail.[2][3] Built in 1870, the now Grade II listed building had become the headquarters of the Metropolitan Borough of Poplar in 1900.[4]

The original building had been the scene of the Poplar Rates Rebellion, led by George Lansbury, which resulted in 19 councilors being put in prison in 1921.[5] The council sold the old town hall to a developer in 2011 and it was subsequently converted into a hotel.[5][6][7]

In the 1930s, civic leaders decided the building was inadequate for their needs and that they would procure a new town hall: the site chosen for the new building had been occupied by a 19th century vestry hall.[4] The foundation stone for the new building was laid by the former mayor, Alderman Charles Key, on 8 May 1937.[8] It was designed by Culpin and Son in the Modernist style in a shape that took the form of a trapezoid.[1] The design involved a rounded frontage at the junction of Bow Road and Fairfield Road; there were layers of continuous stone facing panels above and below a continuous band of glazing on the first, second and third floors.[4] The Builders, a frieze by sculptor David Evans on the face of the building, was unveiled by Lansbury at the official opening of the building on 10 December 1938.[1] Made of Portland stone panels, it commemorated the trades constructing the town hall and symbolised the borough's relationship with the River Thames and the youth of Poplar.[9] The principal rooms were the council chamber, the mayor's parlour and an assembly hall which benefited from a sprung Canadian maple dance floor.[10]

The building was proclaimed by the council to be the first town hall to be erected in the modernist style[4] but ceased to function as the local seat of government when the enlarged London Borough of Tower Hamlets was formed in 1965.[11]

After being used as workspace by the council until the mid-1980s, the town hall was sold in the 1990s to a developer who added a roof extension and converted it for commercial use.[10] It was subsequently used as a business centre.[4]

References

- Historic England. "Former Poplar Town Hall (Bow House), 157 Bow Road (1393151)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 15 May 2020.

- Historic England. "Old Poplar Town Hall and Council Offices (1260135)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 15 May 2020.

- "Old Poplar Town Hall". London Remembers. Archived from the original on 13 August 2022. Retrieved 15 May 2020.

- Smith, Joanna (1998). "Greater London | Tower Hamlets | Bow Road | Bow House (Formerly Poplar Town Hall) (1993-08-03)". London's Town Halls (PDF) (Report). 93/1998. Historic England. pp. 180–181. Retrieved 26 August 2023.

- Brooke, Mike (22 January 2014). "Fury at Tower Hamlets over knock-down sale of old Poplar Town Hall". East London Advertiser. Archived from the original on 13 February 2022. Retrieved 15 May 2020.

- "Poplar Town Hall owner Mujibul Islam receives apology and damages from The Telegraph in libel case". East London News. 13 May 2016. Archived from the original on 21 May 2022. Retrieved 15 May 2020.

- "New checks to stop any more Tower Hamlets 'bargain' sell-offs like Poplar Town Hall". Docklands & East London Advertiser. 17 May 2016. Retrieved 25 April 2020.

- Boardman, David. "Bow House - Former Poplar Town Hall, London". manchesterhistory.net. Retrieved 25 April 2020.

- "The Builders: Architect". Public Monuments and Sculpture Association. Archived from the original on 16 July 2011. Retrieved 1 April 2007.

- East, John; Rutt, Nicola, eds. (24 March 2012). "The Civic Plunge Revisited" (PDF). The Twentieth Century Society. pp. 27–28. Retrieved 25 April 2020.

- "Local Government Act 1963". Legislation.gov.uk. Retrieved 25 April 2020.