Battle of Port Royal

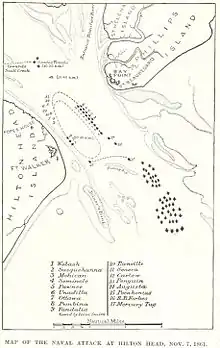

The Battle of Port Royal was one of the earliest amphibious operations of the American Civil War, in which a United States Navy fleet and United States Army expeditionary force captured Port Royal Sound, South Carolina, between Savannah, Georgia and Charleston, South Carolina, on November 7, 1861. The sound was guarded by two forts on opposite sides of the entrance, Fort Walker on Hilton Head Island to the south and Fort Beauregard on Phillip's Island to the north. A small force of four gunboats supported the forts, but did not materially affect the battle.

| Battle of Port Royal | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the American Civil War | |||||||

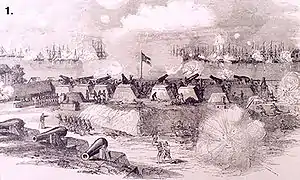

View of the battle from the Confederate heights by Rossiter Johnson | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

77 vessels 12,653 troops |

44 cannons 3,077 troops 4 gunboats | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 31 (8 killed, 23 wounded) | 63 (11 killed, 48 wounded, 4 missing) | ||||||

The attacking force assembled outside of the sound beginning on November 3 after being battered by a storm during their journey down the coast. Because of losses in the storm, the army was not able to land, so the battle was reduced to a contest between ship-based guns and those on shore.

The fleet moved to the attack on November 7, after more delays caused by the weather during which additional troops were brought into Fort Walker. Flag Officer Samuel F. Du Pont ordered his ships to keep moving in an elliptical path, bombarding Fort Walker on one leg and Fort Beauregard on the other; the tactic had recently been used effectively at the Battle of Hatteras Inlet. His plan soon broke down, however, and most ships took enfilading positions that exploited a weakness in Fort Walker. The Confederate gunboats put in a token appearance, but fled up a nearby creek when challenged. Early in the afternoon, most of the guns in the fort were out of action, and the soldiers manning them fled to the rear. A landing party from the flagship took possession of the fort.

When Fort Walker fell, the commander of Fort Beauregard across the sound feared that his soldiers would soon be cut off with no way to escape, so he ordered them to abandon the fort. Another landing party took possession of the fort and raised the Union flag the next day.

Despite the heavy volume of fire, loss of life on both sides was low, at least by standards set later during the American Civil War. Only eight were killed in the fleet and eleven on shore, with four other Southerners missing. Total casualties came to less than 100.

Preparations

Development of Northern strategy

Early in the war, the U.S. Navy had the responsibility of blockading the Southern coastline, but found this task difficult when forced to rely on fueling and resupply ports in the North for its coal-fired steamships. The problems of the blockade were considered by a commission appointed by Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles. Chairman of the commission was Capt. Samuel Francis Du Pont.[1]

The commission stated its views of the South Carolina coast in its second report, dated July 13. In order to improve the blockade of Charleston, they considered seizing a nearby port. They gave particular attention to three: Bull's Bay to the north of Charleston, and St. Helena Sound and Port Royal Sound to the south. The latter two would also be useful in the blockade of Savannah. They considered Port Royal to be the best harbor, but believed that it would be strongly defended and therefore were reluctant to recommend that it be taken.[2]

Southern preparations

Shortly after the bombardment of Fort Sumter in Charleston Harbor had started the war, Confederate Brigadier General P. G. T. Beauregard did not believe that Port Royal Sound could be adequately defended, as forts on opposite sides of the sound would be too far apart for mutual support. Overruled by South Carolina Governor Francis Pickens, he drew up plans for two forts at the entrance. Soon called away to serve the Confederate Army in Virginia, he turned the task of implementing his plans over to Maj. Francis D. Lee of the South Carolina Army Engineers.[3] Before the war, Lee had been an architect, and had designed several churches in Charleston.[4]

Work on the two forts began in July 1861, but progressed only slowly. Labor for the construction was obtained by requisitions of slave labor from local farms and plantations, which the owners were reluctant to provide. Construction was not complete when the attack came.[5] Beauregard's plan was also altered because the heavy guns he wanted were not available. To compensate for the reduced weight of fire by increased volume, the number of guns in the water battery of Fort Walker was increased from seven 10 in (250 mm) columbiads to 12 guns of smaller caliber, plus a single 10 in (250 mm). Fitting the increased number into the available space required that the traverses be eliminated. The battery was therefore vulnerable to enfilade.[6] In addition to the 13 guns of the water battery, Fort Walker had another seven guns mounted to repel land attacks from the rear and three on the right wing. Two other guns were in the fort, but were not mounted.[7] Fort Beauregard was almost as strong; it also had 13 guns that bore on the channel, plus six others for protection against land attacks.[8] The garrisons were increased in size; 687 men were in and near Fort Wagner in mid-August. On November 6, another 450 infantry and 50 artillerymen were added, and 650 more came from Georgia the same day.[9] Because of its isolated position, the garrison of Fort Beauregard could not be easily increased. The force on Philip's Island was 640 men, of whom 149 were in the fort and the remainder infantry defending against land assault.[10] For lack of transportation, all of the late-arriving troops were retained at Fort Walker.

While the forts were being built, the state of Georgia was forming a rudimentary navy by converting a few tugs and other harbor craft into gunboats. Although they could not face the ships of the US Navy on the open seas, their shallow draft enabled them to move freely about in the inland waters along the coasts of South Carolina and Georgia. They were commanded by Flag Officer Josiah Tattnall III. When the Georgia navy was transferred to and became part of the Confederate States Navy, Tattnall found himself in charge of the coastal defenses of both South Carolina and Georgia. He had four gunboats in the vicinity of Port Royal Sound; one was a converted coaster, and three were former tugs. Each mounted only two guns.[11]

Command

Federal army and navy

Throughout the summer of 1861, the task of blockading the entire Atlantic coast of the Confederacy was assigned to the U.S. Navy's Atlantic Blockading Squadron. Because of the great distances involved, the squadron was split in mid-September. Responsibility for the coast south of the North Carolina–South Carolina state line was given to the South Atlantic Blockading Squadron. Command of the new squadron was given to Du Pont, who henceforth was addressed as Flag Officer Du Pont.[12] Du Pont did not assume command immediately, as he continued to prepare for the attack.[13]

As retaining possession of shore facilities would require land forces, getting the cooperation of the U.S. Army was among the first requirements. The War Department agreed to furnish 13,000 troops, to be commanded by Brigadier General Thomas W. Sherman. Sherman's force was organized into three brigades, under Brigadier Generals Egbert L. Viele, Isaac I. Stevens, and Horatio G. Wright.[14] Serious planning was thereafter done by Du Pont, Sherman, Wright, and the Quartermaster General, Brigadier General Montgomery C. Meigs.[15]

Confederate army

In the months preceding the battle, the army in South Carolina went through several changes in leadership. On May 27, 1861, Beauregard left, being called to serve with the Confederate States (CS) Army in Virginia. Command of the state volunteer forces was then transferred to Colonel Richard H. Anderson.[16] Anderson was in turn replaced by Brigadier General Roswell S. Ripley of the CS Army, who on August 21, 1861 was assigned to command of the Department of South Carolina.[17] The final relevant change at the top took place almost on the eve of battle, on November 5, 1861, when the coasts of South Carolina, Georgia, and East Florida were constituted a military department under the command of General Robert E. Lee.[18] (General Lee was not closely related to Major Francis D. Lee, the engineer responsible for building Forts Walker and Beauregard.) None of these changes was particularly important, as most attention was given to more active parts of the war than Port Royal Sound.

The most important change of command directly affecting the forts took place on October 17, 1861, when Brigadier General Thomas F. Drayton was assigned to the Third Military District of the Department of South Carolina, which meant that the forts were in his jurisdiction.[19] Drayton, who was a member of a prominent Charleston family and a graduate of the United States Military Academy, remained in command through the actions of November 7. Whether he could have hastened the preparations of the forts for battle is debatable; the fact is that he did not.

The expedition

Although preparations for battle proceeded throughout the summer and early fall of 1861, the schedule proposed by the administration could not be met. As late as September 18, President Lincoln could still advocate a start date of October 1. Du Pont felt that the Navy Department was rushing him in without proper preparation.[20] Despite his reservations, the force was assembled — the soldiers and their transports at Annapolis, Maryland, the sailors and warships at New York. The two branches rendezvoused at Hampton Roads. Bad weather delayed departure from there by another week, during which time Du Pont and Sherman were able to make final arrangements. Among the issues to be settled was the target; up until this time, the decision of whether to strike at Bull's Bay or Port Royal had not been made. Only after he was sure that the latter would meet future needs of the fleet, and Bull's Bay would not, did Du Pont finally commit the expedition to the attack on Port Royal.[21]

On October 28, 25 coal and ammunition vessels departed Hampton Roads, accompanied by two warships, Vandalia and Gem of the Sea. The remainder of the fleet, including 17 warships and all of the army transports, put out to sea the next day. The full fleet of 77 vessels was the largest assemblage of ships that had ever sailed under the American flag; the distinction would not last long. In an effort to maintain secrecy, Du Pont had not told anyone other than his immediate staff the destination. He had given each captain a sealed envelope, to be opened only at sea. The message given to Captain Francis S. Haggerty of Vandalia is typical: "Port Royal, S. C., is the port of destination for yourself and the ships of your convoy."[22]

Efforts at secrecy notwithstanding, almost everything about the expedition except its target was known to the entire world. 2 days before departure of the main fleet, the New York Times carried a front-page article entitled "The Great Naval Expedition," in which the full order of battle down to regimental level was laid out for all to see.[23] The article was repeated, word for word, in the Charleston newspapers of November 1. Although Du Pont and others muttered aloud about treason and leaks in high places, the article was in fact the product of straightforward journalism. The author had gained most of his information by mingling with soldiers and sailors. No one had thought to sequester the men from the populace, even though the loyalties of the citizens of Maryland and Hampton Roads were divided. (Perhaps some real espionage was also available. Although the destination was supposed to be unknown until after the fleet sailed, acting Confederate Secretary of War Judah P. Benjamin on November 1 telegraphed the South Carolina authorities that "the enemy's expedition is intended for Port Royal."[24])

The fleet maintained its formation as it moved down the coast until it had passed Cape Hatteras. As it passed into South Carolina waters on November 1, however, the wind increased to gale force, and in mid-afternoon Du Pont ordered the fleet to disregard the order of sailing.[25] Most of the ships managed to ride out the storm, but some had to abort their mission and return home for repairs, and others were lost. Gunboat Isaac Smith had to jettison most of her guns in order to stay afloat. Three ships carrying food and ammunition were sunk or driven ashore without loss of life: Union, Peerless, and Osceola. Transport Governor, carrying 300 Marines, went down; most of her contingent were saved, but seven men were drowned or otherwise lost in the rescue.[26]

The scattered ships began to arrive at the entrance to Port Royal Sound on November 3, and continued to straggle in for the next four days.[27] The first day, November 4, was devoted to preparing new charts for the sound. The Coast Survey vessel Vixen, under her civilian captain Charles Boutelle, accompanied by gunboats Ottawa, Seneca, Pembina, and Penguin, entered the harbor and confirmed that the water was deep enough for all ships in the fleet. Confederate Flag Officer Josiah Tattnall III took his small flotilla, consisting of the gunboats CSS Savannah, Resolute, Lady Davis, and Sampson out to interfere with their measurements, but the superior firepower of the Union gunboats forced them to retire.[28]

Early in the morning of November 5, gunboats Ottawa, Seneca, Pembina, Curlew, Isaac Smith, and Pawnee, made another incursion into the harbor, this time seeking to draw enemy fire so as to gauge their strength. Again the Confederate flotilla came out to meet them, and again they were driven back.[29]

At about the time that the gunboats returned to the anchorage and the captains of the warships assembled to formulate plans for the assault on the forts, General Sherman informed Du Pont that the army could not take part in the operation. The loss of his ships in the storm had deprived him of his landing boats as well as much of his needed ammunition. Furthermore, his transports were not combat loaded. Sherman would not commit his troops until the arrival of transport Ocean Express, carrying most of his small ammunition and heavy ordnance, and delayed by the storm. She would not arrive until after the battle was over.[30]

Unwilling to cancel the operation at this point, Du Pont ordered his fleet to attack, concentrating their fire on Fort Walker. As they moved in, however, flagship Wabash, drawing 22 ft (6.7 m), grounded on Fishing Rip Shoal. By the time she was worked free, the day was too far gone to continue the attack.[31]

The weather on the next day, November 6, was stormy, so Du Pont postponed the attack for one more day. During the delay, Commander Charles Henry Davis, Du Pont's fleet captain and chief of staff, had the idea of keeping the ships in motion while bombarding the forts. This was a tactic that had recently been used successfully at the Battle of Hatteras Inlet. He presented his idea to the flag officer, who agreed. The plan as completed by Du Pont called for his fleet to enter the harbor at mid-channel. On the way in, they would engage both forts. After passing the forts, the heaviest ships would execute a turn to the left in column and go back against Fort Walker. Again past the fort, they would once more turn in column, and repeat the maneuver until the issue was decided. While the main fleet was thus engaged, five of his lighter gunboats would form a flanking column that would proceed to the head of the harbor and shield the rest of the fleet from Tattnall's flotilla.[32][33]

Battle

On November 7, the air was calm and gave no further reason for delay. The fleet was drawn up into 2 columns and moved to the attack. The main body consisted of 9 ships with guns and one without. In order, they were flagship Wabash, Susquehanna, Mohican, Seminole, Pawnee, Unadilla, Ottawa, Pembina, Isaac Smith, and Vandalia. Isaac Smith had jettisoned her guns during the storm, but she would now contribute by towing the sailing vessel Vandalia. Five gunboats formed the flanking column: Bienville, Seneca, Penguin, Curlew, and Augusta. Three other gunboats, R. B. Forbes, Mercury, and Penguin remained behind to protect the transports.[34]

The fight started at 09:26, when a gun in Fort Walker fired on the approaching fleet. (This first shell exploded harmlessly a short distance out of the muzzle.) Other shots followed, the fleet replied by firing on both forts, and the action became general. Shells from the fleet ripped into the forts, although many of them passed harmlessly overhead and landed well beyond. Because the motion of the ships disrupted their aim, most of the shots from the forts missed; generally, they aimed too high, sending the missiles that were on target into the masts and upper works of the vessels. The ships proceeded according to Du Pont's orders through the first turn, but then the plan fell apart. First to leave was the third ship in the main column, Mohican, under Commander Sylvanus W. Godon. Godon found that he could enfilade the water battery from a position safe from return fire, so he dropped out. Those following him were confused, so they also dropped out. Only Wabash and Susquehanna continued in the line of battle. The two ships made their second and third passes, and then were joined, inexplicably, by gunboat Bienville.[35]

The bombardment continued in this way until shortly after noon, when Pocahontas, delayed by the storm, put in her appearance. Her captain, Commander Percival Drayton, placed the ship in position to enfilade Fort Walker and joined the battle. Commander Drayton was the brother of Thomas F. Drayton, the Confederate general who commanded the forces ashore.[36]

Ashore, Fort Walker was suffering, with most of the damage being done by the ships that had dropped out of the line of battle. The exhausted gunners had only three guns left in the water battery, the others being disabled. About 12:30, General Drayton left the fort to collect some reserves to replace the men in the fort. Before leaving, he turned command over to Colonel William C. Heyward, with instructions to hold out as long as possible. As he was returning at 14:00, he found the men leaving the fort. They explained that they were almost out of powder for the guns, and had therefore abandoned their position.[37]

The departure of the soldiers from the fort was noticed by sailors in the fleet, and signal was soon passed to cease fire. A boat crew led by Commander John Rodgers went ashore under a flag of truce and found the fort abandoned. Rodgers therefore raised the Union flag.[38] No effort was made to further press the men who had just left the fort, so the entire surviving Confederate force was permitted to escape to the mainland.

Fort Beauregard had not suffered punishment as severe as that given to Fort Walker, but Colonel Robert Gill Mills Dunovant was concerned that the enemy could easily cut off his only line of retreat. When the firing at Fort Walker ceased and cheering in the fleet was heard, he realized that his command was in peril. Rather than be trapped, he ordered the troops on Philip's Island to abandon their positions. This they did without destroying their stores, because to do so would have attracted the attention of the fleet. Their departure was not noted, and not until a probing attack by gunboat Seneca elicited no reply was it realized that the fort was unmanned. As it was then very late in the day, raising the Union flag on Fort Beauregard was delayed until the following morning.[39]

Aftermath

The battle being over, personnel losses could be determined. Despite the large expenditure of shot and shell by both sides, casualties were rather light. In the Southern forts, 11 men had been killed, 47 were wounded, and 4 were missing.[40] In the Northern fleet, 8 were killed and 23 wounded. These numbers do not include those lost in the sinking of transport Governor.[41]

Immediately following the capture of the forts, the Union forces consolidated their victory by occupying Beaufort, and then moved north by next taking St. Helena Sound. The northward expansion continued up to the rivers on the south side of Charleston, where it was halted. Thus, the siege of Charleston, which continued until the last days of the war, can be said to have been initiated at Port Royal Sound.[42]

General Lee, who had been placed in command too late to affect the battle, decided that he would not contest the Union gunboats. He withdrew his forces from the coast and defended only vital interior positions. He was able to thwart Federal efforts to cut the vital railroad link between Savannah and Charleston.[43] Lee's strategy was maintained even after he was recalled to Richmond and given command of the Army of Northern Virginia, where he earned his fame.

Flag Officer Du Pont was widely honored for his part in the victory. When the rank of rear admiral was created for the U.S. Navy in July 1862, he was the second person (after David G. Farragut) to be promoted. He retained command of the South Atlantic Blockading Squadron, and directed continuing naval operations against the coast, including Charleston, Savannah, and Fernandina, Florida. To that end, he set up extensive works at Port Royal Sound for maintaining the fleet, including coaling, provisioning, and repair facilities.[44] Unfortunately, Du Pont proved to be unduly cautious, and his reputation could not survive the failure of the fleet attack on Charleston of April 7, 1863. He soon thereafter retired from the service.[45]

General Sherman continued to serve in various capacities throughout the war, but without distinction. His abrasive personality made him difficult to work with, so he was shunted off to lesser commands. He lost his right leg in combat at Port Hudson.[46]

After a Union victory, Confederate Brigadier-General Thomas F. Drayton directed the evacuation of rebel forces from Hilton Head Island to the Bluffton mainland. Occupying Port Royal Harbor, the Union’s South Atlantic Blockading Squadron could then be monitored by rebel lookouts disbursed from Bluffton’s substantial picket headquarters. Bluffton’s geographic location resulted in it being the only strategic position on the east coast where the Confederates could gather direct intelligence on the Union squadron, which conducted crucial blockade operations along the southern coastline in the aftermath of the battle.[47]

General Drayton proved to be incompetent in the field, so he was put in various administrative positions.[48]

The aftermath of the battle and the resultant freeing of the slaves was described by John Greenleaf Whittier in his poem "At Port Royal."[49]

References

Abbreviations used:

- ORA (Official records, armies): War of the Rebellion: a compilation of the official records of the Union and Confederate Armies.

- ORN (Official records, navies): Official records of the Union and Confederate Navies in the War of the Rebellion.

- Browning, Success is all that was expected, p. 14. The Blockade Strategy Board was often called the Du Pont Board, in reference to its senior member.

- ORA I, v. 53, pp. 67–73.

- Reed, Combined operations, p. 26. ORA I, v. 6, pp. 18–20.

- Who was who in America, Historical volume, entry for Francis D. Lee.

- Reed, Combined operations, p. 26.

- Reed, Combined operations, pp. 26–27.

- ORN I, v. 12, p. 279.

- ORN I, v. 12, p. 301.

- ORN I, v. 12, pp. 301–302.

- ORN I, v. 12, p. 304.

- Browning, Success is all that was expected, pp. 19, 31. ORN I, v. 12, p. 295.

- "Flag Officer" was a billet, not a rank. Commanders of naval squadrons and major shore installations retained their commissioned ranks as captains, but were customarily addressed as flag officers because they flew their personal flags.

- Browning, Success is all that was expected, pp. 21–22, 24.

- Browning, Success is all that was expected, p. 24. T. W. Sherman is not related to the more famous William Tecumseh Sherman.

- Browning,Success is all that was expected, p. 25.

- ORA I, v. 53, pp. 176–177.

- ORA I, v. 6, p. 1.

- ORA I, v. 6, p. 309.

- OAR I, v. 6, pp. 6–313; ORN I, v. 12, pp. 300–307.

- Browning, Success is all that was expected, p. 25. ORN I, v. 12, p. 208.

- Browning, Success is all that was expected, pp. 27–28.

- ORN I, v. 12, p. 229.

- New York Times, October 26, 1861.

- Ammen, The Atlantic coast, p. 16.

- Browning, Success is all that was expected, p. 28.

- Browning, Success is all that was expected, pp. 29–30. ORN I, v. 12, pp. 233–235.

- Browning, Success is all that was expected, pp. 29, 39.

- Browning, Success is all that was expected, pp. 30–31.

- Browning, Success is all that was expected, p. 31.

- Browning, Success is all that was expected, p. 32.

- Browning, Success is all that was expected, p. 34.

- Browning, Success is all that was expected, p. 35.

- ORN I, v. 12, pp. 262–266. This report (including map) describes the battle as it would have been had it gone according to plan. For reasons of his own, Du Pont did not describe it the way it actually took place. Many historians rely on this report for their accounts of the battle.

- Browning, Success is all that was expected, pp. 35–36.

- Browning, Success is all that was expected, p. 38.

- Browning, Success is all that was expected, p. 39.

- ORN I, v. 12, p. 303.

- Browning, Success is all that was expected, p. 40.

- Ammen, Atlantic coast, pp. 28–29. The "commanding officer of the Seneca" to whom he refers was Lieutenant Daniel Ammen.

- ORN I, v. 12, p. 306.

- ORN I, v. 12, p. 266.

- ORN I, v. 12, pp. 319–324, 386–390.

- ORA I, v. 6, p. 367.

- Browning, Success is all that was expected, pp. 77ff.

- Faust, Encyclopedia of the Civil War, entry for Samuel Francis Du Pont.

- Faust, Encyclopedia of the Civil War, entry for Thomas West Sherman.

- Jeff Fulgham, The Bluffton Expedition: The Burning of Bluffton, South Carolina, During the Civil War (Bluffton, S.C.: Jeff Fulgham, 2012), 46–51.

- Faust, Encyclopedia of the Civil War, entry for Thomas Fenwick Drayton.

- Whittier, John Greenleaf (1864). In War Time and Other Poems. Boston: Ticknor and Fields. pp. 51-57.

Bibliography

- Ammen, Daniel, The Atlantic Coast. The Navy in the Civil War—II Charles Scribner's Sons, 1883. Reprint, Blue and Gray Press, n.d.

- Browning, Robert M. Jr., Success is all that was expected; the South Atlantic Blockading Squadron during the Civil War. Brassey's, 2002. ISBN 1-57488-514-6

- Faust, Patricia L., Historical Time Illustrated encyclopedia of the Civil War. Harper and Row, 1986.

- Johnson, Robert Underwood, and Clarence Clough Buel, Battles and leaders of the Civil War. Century, 1887, 1888; reprint ed., Castle, n.d.

- Ammen, Daniel, "Du Pont and the Port Royal expedition," vol. I, pp. 671–691.

- Reed, Rowena, Combined operations in the Civil War. Naval Institute Press, 1978. ISBN 0-87021-122-6

- US Navy Department, Official records of the Union and Confederate Navies in the War of the Rebellion. Series I: 27 volumes. Series II: 3 volumes. Washington: Government Printing Office, 1894–1922. Series I, volume 12 is most useful.

- US War Department, A compilation of the official records of the Union and Confederate Armies. Series I: 53 volumes. Series II: 8 volumes. Series III: 5 volumes. Series IV: 4 volumes. Washington: Government Printing Office, 1886–1901. Series I, volume 6 is most useful.The War of the Rebellion