Portraits of Frederick the Great

Frederick the Great was the subject of many portraits. Many were painted during Frederick's life, and he would give portraits of himself as gifts. Almost all portraits of Frederick are idealized and do not reflect how he looked according to his death mask. It has been suggested that the most accurate representation of Frederick may be the picture of a flautist from William Hogarth's series Marriage A-la-Mode.

Paintings and etchings

During the lifetime of Frederick the Great a large number of idealized portraits were made of him by many painters and engravers, among them Antoine Pesne, Georg Wenzeslaus von Knobelsdorff, Johann Georg Ziesenis,[1][2] Gottfried Hempel,[3][4][5] Johann Heinrich Christian Franke,[6] Charles-Amédée-Philippe van Loo,[7] Anna Dorothea Therbusch,[8] Anton Graff, Johann Georg Wille,[9] Georg Friedrich Schmidt[10][11][12] and Daniel Chodowiecki.[13][14]

The king gave several of these pictures away as gifts in recognition of rendered services,[15] whether as life-size paintings, miniatures set with diamonds that were worn like medals, or representations on snuff boxes.[16] However, most portraits were produced for commercial reasons without being commissioned by the king, because there was a demand for his likeness from all of the courts of Europe. None of these official portraits show the real facial features of the monarch. In 1897, art historian Paul Seidel complained that no clear judgment could be derived from the surviving portraits as to what Frederick the Great really looked like.[17]

The French Rococo painter Antoine Pesne (1683–1757),[18] who worked at the Prussian court for many years and was appointed director of the Berlin Academy of Arts, chiefly depicted Frederick in his younger years, his earliest portrait being that of Frederick with his older sister, Wilhelmine, as children (c.1714-15).[19] Several times he painted the crown prince[20][21] and young king[22][23] in a representational style with smooth features. With some justification, critics accused Pesne of portraying all of his royal sitters equally beautifully and lacking any sharper characterization.[24] Indeed, Pesne’s idealized representations of Frederick do not correspond with a statement by the Austrian ambassador Friedrich Heinrich Graf von Seckendorff about the 14-year-old crown prince that he looked "old and stiff" at a young age and acted accordingly presumably because of the hardships imposed on him by his father.[25] Significantly, even the latter said, when the English royal family had asked him for a portrait of the crown prince, that they should have a large monkey painted because that was Frederick’s likeness.[26]

Georg Wenzeslaus von Knobelsdorff seems to have invented a pictorial formula that depicted the crown prince in profile with a classically straightened nose,[27] which must have had an immense influence on countless later profile portraits of the king that were widely distributed through prints.[28][29]

In 1763 Johann Georg Ziesenis produced a "bourgeois" portrait of the king which has been claimed to be the only painting for which Frederick sat during his lifetime.[30] It was commissioned by Frederick's sister, Duchess Philippine Charlotte of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel.[31] However, more recent researchers have doubts as to whether the king actually sat for this painting from 17 to 20 June 1763 at Castle Salzdahlum,[32] especially since the artist made Frederick’s facial features look far too handsome. In 1763, at the end of the Seven Years' War, Frederick "complained in his letters of how much weight he had lost and how thin, fragile, and gray he had become." Ziesenis's portrait hardly agrees with this.[33]

When the French painter Charles-Amédée-Philippe van Loo stayed in Berlin from 1763 to 1769, he painted at least two portraits of the Prussian king, one of which has been in the royal collection in London since 1816.[34][35] According to Paul Seidel, the artist put the “stamp of unnatural” on these portraits of Frederick. “You can see at first glance that they are painted from memory and without a sitting.”[36]

Such images, based on Knobelsdorff’s and Pesne’s idealized portraiture, dominated both in painted and engraved form until the 1760s. However, after the Seven Years' War, the conception of Frederick portraits seems to have changed, now even allowing the depiction of individual shortcomings or the effects of experienced stress. At the same time, in connection with an intensive formation of legends about the military successes of the king, the emergence of an “age type” can be observed both in painting and sculpture.[37] By emphasizing the sharp nasolabial folds, the straight lines of the forehead and the bridge of the nose, the narrow mouth and the protruding eyes the artists created a type of image that art historian Helmut Börsch-Supan has characterized as “very Prussian in its expressive frugality to the point of scantiness.”[38]

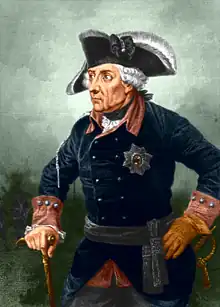

A very popular depiction of Frederick in the new style is the portrait painted by Johann Heinrich Christian Franke in 1763/64, of which a number of variants exist.[39] It shows a bourgeois king holding up his tricorne in greeting. The monarch was well known for frequently saluting in public with his “cocked hat.”[40]

In 1767, Anton Friedrich König (1722-1787) was appointed royal court miniature portrait painter for Frederick the Great. In 1769, he produced a watercolour painting on ivory showing the king as an intellectual writer, historian and philosopher in front of his writing table, surrounded by the books in his library.[41]

In a gouache of 1772 by Daniel Chodowiecki the king is posed rather awkwardly in a slightly bent position on horseback, a representation that circulated in numerous copies[42] and engraved versions. A print after it was later used by Johann Caspar Lavater as an illustration for his Physiognomische Fragmente (1777), because the author was of the opinion that here "the Great, He himself, was riding past," as he believed he knew him from life.[43]

When in 1775 Frederick sent Voltaire the portrait that Anna Dorothea Therbusch had painted of him,[44] he ironically said: “In order not to dishonour her brush, she has adorned my contorted face with the grace of youth.”[45] Only a few years later, Therbusch's brother Christoph Friedrich Reinhold Lisiewski painted a portrait of the Prussian king that looks very different from his sister's,[46] which is all the more surprising given that the siblings often collaborated on their paintings.[47]

In 1781 Anton Graff painted Frederick the Great for the Prussian envoy in Dresden, Philipp Karl von Alvensleben. For this portrait and some later copies the monarch never sat. The artist is said to have observed the king from a distance when he attended a military parade and then made the picture from memory.[48] It shows a bourgeois-looking king and, in its concentration on the physiognomy, reflects Graff's portrait style more than a king's claim to representation.[49] Helmut Börsch-Supan assumes that Graff only corrected the facial features that he found “carved” in Franke’s portrait in order to make them “more carnal, softer and human.”[50]

In the case of eighteenth-century portraits of monarchs, less importance was attached to the likeness of the sitters, and more to the political and social role in which they wanted to be represented in public. For example, they were shown as rulers with scepter and ermine cloak[51] or as competent military leaders, not what they looked like in their everyday life.[52][53] According to art historian Frauke Mankartz, the recognizable "brand" was more important than realism.[54] The king himself often said that his portraits did not resemble him,[55] and his contemporaries, including Emperor Joseph II,[56] were of the opinion that not a single painting depicted his face truthfully.[57]

Indeed, Frederick had a pronounced aversion to sitting for portraits, which he consistently refused because he was convinced that he was ugly. "You have to be Apollo, Mars or Adonis to be painted, but since I do not have the honour of resembling one of these gentlemen, I have withdrawn my face from the painters' brush as much as it depended on me," he wrote to Jean-Baptiste le Rond d'Alembert in 1774.[59] Furthermore, he said to the Marquis d’Argens: "There is so much talk about the fact that we terrestrial kings are made in the image of God. Then I look in the mirror and am obliged to say to myself: How unlucky for God!"[60] After extensive analysis of different types of Frederick portraits, Andrea M. Kluxen arrives at the conclusion that there is no realistic image that accurately depicts Frederick's (ugly) facial features.[61]

The death mask of him, taken by John Eckstein on 17 August 1786,[62][63] demonstrates precisely what had led the king to his conviction that he was extremely ugly: Frederick had a prominently hooked nose and little else to make him look handsome. This aquiline nose is not depicted in the official painted portraits. In her analysis of Frederick busts and statues, Saskia Hüneke also noticed that nearly all of them depict the nose in a relatively straight line. "In comparison, the wax pouring from the original form of the death mask does not show this line, so that it is more an ideal of the ancient Greek profile".[64]

Only one artist seems to have shown the Prussian king as he really was, namely with an aquiline nose and playing the flute in front of a symbol of homosexuality: William Hogarth in scene 4 of his satirical series Marriage A-la-Mode. The picture is entitled The Toilette and was completed in 1744. The features of the flautist depicted on the left[65][66] bear a striking resemblance to the death mask of Frederick,[58][67] as does the face of the flautist in Simon François Ravenet's reversed engraving after Hogarth's painting (1745).

In the nineteenth century, the king became a popular subject in historical paintings and prints. Adolph Menzel depicted events from the life of Frederick both in the wood-engravings to illustrate the Geschichte Friedrichs des Grossen by Franz Kugler[68][69] and in several of his paintings, including Frederick the Great Playing the Flute at Sanssouci as the most famous work.[70] In these pictures he continues to avoid representing Frederick with a crooked nose, although he must have known the death mask of the Prussian king.[71]

Monuments

As during his lifetime Frederick protested against being depicted in monuments, only after his death numerous monuments were erected, including Johann Gottfried Schadow's Szczecin marble statue (1793)[72] and Christian Daniel Rauch's Equestrian statue of Frederick the Great (Berlin, 1851).[73]

Gallery

Painting as 24-year-old Crown Prince of Prussia by Antoine Pesne, 1736

Painting as 24-year-old Crown Prince of Prussia by Antoine Pesne, 1736.jpg.webp) Painting as Crown Prince of Prussia by Georg Wenzeslaus von Knobelsdorff, 1737

Painting as Crown Prince of Prussia by Georg Wenzeslaus von Knobelsdorff, 1737.jpg.webp) Painting as Crown Prince wearing an ermine-lined, purple coronation cloak by Antoine Pesne, 1739

Painting as Crown Prince wearing an ermine-lined, purple coronation cloak by Antoine Pesne, 1739_-_Nationalmuseum_-_15767.tif.jpg.webp) Painting during his early reign by Antoine Pesne, early 1740s

Painting during his early reign by Antoine Pesne, early 1740s Painting as King of Prussia by Antoine Pesne, c.1745

Painting as King of Prussia by Antoine Pesne, c.1745.jpg.webp) Painting by Johann Georg Ziesenis, 1763

Painting by Johann Georg Ziesenis, 1763.jpg.webp) Painting by Johann Heinrich Christian Franke, 1764

Painting by Johann Heinrich Christian Franke, 1764 Painting by Anna Dorothea Therbusch, 1772

Painting by Anna Dorothea Therbusch, 1772 Painting by Wilhelm Camphausen, 1870

Painting by Wilhelm Camphausen, 1870 Engraving by unknown illustrator, 1871

Engraving by unknown illustrator, 1871

Statue of Frederick the Great, marble by Johann Gottfried Schadow, 1793

Statue of Frederick the Great, marble by Johann Gottfried Schadow, 1793 Frederick the Great with his Italian Greyhounds, bronze by Johann Gottfried Schadow, 1822

Frederick the Great with his Italian Greyhounds, bronze by Johann Gottfried Schadow, 1822 Statue of Frederick the Great in front of Schloss Charlottenburg, Berlin

Statue of Frederick the Great in front of Schloss Charlottenburg, Berlin Equestrian statue of Frederick the Great, Unter den Linden, Berlin. Bronze by Christian Daniel Rauch, 1851

Equestrian statue of Frederick the Great, Unter den Linden, Berlin. Bronze by Christian Daniel Rauch, 1851

References

- See Portrait of Frederick II of Prussia by Johann Georg Ziesenis.

- Frederick the Great portrait auctioned for €670,000

- Gottfried Hempel, Portrait of Frederick the Great, Bavarian State Painting Collections, Munich.

- Gleimhaus Museum der deutschen Aufklärung: Porträt Friedrichs des Großen, c.1760.

- Reimar F. Lacher, "Friedrich, unser Held": Gleim und sein König (Göttingen: Wallstein Verlag, 2017), pp. 9-11.

- "Johann Heinrich Christian Franke, Portrait of Frederick the Great".

- Royal Collection Trust: Charles-Amédée-Philippe van Loo, Frederick II, King of Prussia (1763-69).

- Anna Dorothea Therbusch, Frederick the Great (c.1775).

- Princeton University Art Museum: Johann Georg Wille, Frederic II King of Prussia, engraving, 1757.

- Tilman Just, Georg Friedrich Schmidt, Chronologisches Verzeichnis seiner Kupferstiche und Radierungen (Universität Heidelberg: arthistoricum.net, 2021), cat. nos. 87 and 98.

- The British Museum: Georg Friedrich Schmidt, Fredericus III Rex Borussiae, engraved portrait of Frederick II of Prussia as Frederick III Elector of Brandenburg, 1743.

- Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, Kupferstich-Kabinett: Georg Friedrich Schmidt, Frederick II, King of Prussia, engraving, 1746.

- University of Oxford: Daniel Chodowiecki, Frederick the Great on his horse (after 1772).

- Kupferstichkabinett, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin: Daniel Chodowiecki, Fridericus Magnus Rex Borussiae (1758).

- Frauke Mankartz: "Die Marke Friedrich: Der preußische König im zeitgenössischen Bild," in Friederisiko: Friedrich der Große: Die Ausstellung, exh. cat., Stiftung Preußische Schlösser und Gärten Berlin-Brandenburg, 2012 (Munich: Hirmer, 2012), pp. 210–215.

- The Metropolitan Museum of Art: Snuffbox cover with portrait of Frederick the Great (1712–1786), King of Prussia

- Paul Seidel: "Die äußere Erscheinung Friedrichs des Großen," in Hohenzollern-Jahrbuch, 1 (1897), p. 87.

- See Gerd Bartoschek, Antoine Pesne, 1683–1757: Ausstellung zum 300. Geburtstag (Potsdam-Sanssouci: Generaldirektion der Staatlichen Schlösser und Gärten, 1983).

- See Antoine Pesne, Frederick, Crown Prince of Prussia, as a child with his sister Wilhelmine (c.1714/15.

- Portrait of Frederick, Crown Prince of Prussia, painting by Antoine Pesne, 1724.

- Portrait of Crown Prince Frederick, painting by Antoine Pesne, c.1736.

- Portrait of Frederick II of Prussia, Hermitage, painting by Antoine Pesne, c.1743.

- Portrait of Frederick II of Prussia, painting by Antoine Pesne, 1745.

- Arnold Hildebrand, Das Bildnis Friedrichs des Großen: Zeitgenössische Darstellungen, 2nd edn (Berlin: Nibelungen-Verlag, 1942), p. 115.

- Paul Seidel, “Die Kinderbildnisse Friedrichs des Großen und seiner Brüder”, Hohenzollern-Jahrbuch, 15 (1911), p. 29.

- Johannes Kunisch, Friedrich der Große: Der König und seine Zeit (Munich: C. H. Beck, 2004), p. 27.

- See Georg Wenzeslaus von Knobelsdorff, Crown Prince Frederick in profile (1737).

- See the overview page of graphic portraits of Frederick in Edwin von Campe, Die graphischen Porträts Friedrichs des Großen aus seiner Zeit und ihre Vorbilder (Munich: Bruckmann, 1958), p. 94.

- Bernd Krysmanski, "Does Hogarth Depict Old Fritz Truthfully with a Crooked Beak? – The Pictures Familiar to Us from Pesne to Menzel Don’t Show This," ARTdok (Heidelberg University: arthistoricum.net, 2022), p. 17.

- Jean Lulvès, Das einzige glaubwürdige Bildnis Friedrichs des Großen als König (Hanover: Hahnsche Buchhandlung, 1913).

- August Fink, “Herzogin Philippine Charlotte und das Bildnis Friedrichs des Großen,” Braunschweigisches Jahrbuch, 40 (1959), pp. 117–135.

- See Karin Schrader, Der Bildnismaler Johann Georg Ziesenis (1717–1776): Leben und Werk mit kritischem Oeuvrekatalog (Münster: LIT, 1995), pp. 101–119.

- See Prussian Palaces and Gardens Foundation Berlin-Brandenburg: Images of Frederick

- See Royal Collection Trust: Charles-Amédée-Philippe van Loo, Frederick II, King of Prussia (1763-69).

- Sir Christopher Clark, “Frederick II – Modest appearance”.

- Paul Seidel, Friedrich der Grosse und die bildende Kunst (Leipzig and Berlin: Giesecke & Devrient, 1922), p. 198.

- Saskia Hüneke, “Friedrich der Grosse in der Bildhauerkunst des 18. und 19. Jahrhunderts,” Jahrbuch/Stiftung Preußische Schlösser und Gärten Berlin-Brandenburg, 2 (1997–1998) (Berlin: Akademie-Verlag, 2001), p. 61.

- Helmut Börsch-Supan, “Die Bildnisse des Königs,” in Friedrich Benninghoven, Helmut Börsch-Supan and Iselin Gundermann (eds.), Friedrich der Grosse: Ausstellung des Geheimen Staatsarchivs Preußischer Kulturbesitz anläßlich des 200. Todestages König Friedrich II. von Preußen (Berlin: Geheimes Staatsarchiv Preußischer Kulturbesitz, 1986), p. XIII.

- See Johann Heinrich Christian Franke, Frederick the Great saluting with his cocked hat, c.1763/64.

- Tim Blanning, Frederick the Great: King of Prussia (London: Penguin Books, 2016), pp. 349-350.

- Anton Friedrich König, Frederick II in his library, watercolour on ivory, 1769.

- University of Oxford: Frederick the Great on his horse after 1772

- Johann Caspar Lavater, Physiognomische Fragmente, zur Beförderung von Menschenkenntniß und Menschenliebe (Leipzig and Winterthur: Weidmanns Erben & Reich; Heinrich Steiner & Compagnie, 1777), Dritter Versuch, p. 348.

- Anna Dorothea Therbusch, Portrait de Frédéric II de Prusse (c.1775).

- Cited by Frauke Mankartz, “Die Marke Friedrich: Der preußische König im zeitgenössischen Bild,” in Friederisiko: Friedrich der Große, exh. cat., Stiftung Preußische Schlösser und Gärten Berlin-Brandenburg (Munich: Hirmer, 2012), Die Ausstellung, p. 209.

- See Christoph Friedrich Reinhold Lisiewski, Frederick the Great (1782).

- See Gerd Bartoschek, “Gemeinsam stark? Anna Dorothea Therbusch und ihre Zusammenarbeit mit Christoph Friedrich Reinhold Lisiewsky”, in Helmut Börsch-Supan and Wolfgang Savelsberg (eds.), Christoph Friedrich Reinhold Lisiewsky (1725–1794) (Berlin and Munich: Deutscher Kunstverlag, 2010), pp. 77–84.

- Ekhart Berckenhagen, Anton Graff: Leben und Werk (Berlin: Deutscher Verlag für Kunstwissenschaft, 1967), p. 19.

- See Stiftung Preußische Gärten und Schlösser Berlin-Brandenburg: König Friedrich II. von Preußen (1712-1786).

- Helmut Börsch-Supan, “Friedrich der Große im zeitgenössischen Bildnis,” in Oswald Hauser (ed.), Friedrich der Grosse in seiner Zeit (Cologne and Vienna: Böhlau, 1987), p. 257.

- See Antoine Pesne's portrait of Frederick II of Prussia.

- Ernst H. Kantorowicz, The King's Two Bodies: A Study in Mediaeval Political Theology (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1957)

- Claudia Breger, "A Hybrid Emperor: The Poetics of National Performance in Kantorowicz's Biography of Frederick II," Colloquia Germanica, 35, nos. 3–4 (2002), pp. 287–310.

- Mankartz, "Die Marke Friedrich: Der preußische König im zeitgenössischen Bild," p. 210.

- In 1772, he wrote to Voltaire: "You will know that … neither my portraits nor my medals are like me." Cited in Arnold Hildebrand, Das Bildnis Friedrichs des Großen: Zeitgenössische Darstellungen, 2nd edition (Berlin: Nibelungen-Verlag, 1942), p. 135.

- In 1769, Joseph II wrote to his mother Maria Theresa about the Prussian King he had met in Neisse: "He does not resemble any of the pictures you have seen of him ." Letter dated 29 August 1769, cited in Gustav Berthold Volz, Friedrich der Grosse im Spiegel seiner Zeit, vol. 2: Siebenjähriger Krieg und Folgezeit bis 1778 (Berlin: Reimar Hobbing, 1901), p. 213.

- Krysmanski, "Does Hogarth depict Old Fritz truthfully with a crooked beak?–the pictures familiar to us from Pesne to Menzel don't show this," pp. 11–13.

- Bernd Krysmanski, Das einzig authentische Porträt des Alten Fritz? Is the only true likeness of Frederick the Great to be found in Hogarth's 'Marriage A-la-Mode'? (Dinslaken, 2015).

- Hans Dollinger, Friedrich II. von Preußen: Sein Bild im Wandel von zwei Jahrhunderten (Munich: List, 1986), p. 82.

- Cited after Gisela Groth, "Wie Friedrich II. wirklich aussah," Preußische Allgemeine Zeitung, 14 November 2012, p. 11.

- Andrea M. Kluxen, Bild eines Königs: Friedrich der Große in der Graphik (Limburg/Lahn: C. A. Starke, 1986), p. 34.

- "Die Werke Friedrichs des Großen, 7, S. uc_p14, Abb. 1". friedrich.uni-trier.de.

- Michael Hertl, Totenmasken: Was vom Leben und Sterben bleibt (Stuttgart: Jan Thorbecke, 2002), pp. 159–163.

- Hüneke: "Friedrich der Große in der Bildhauerkunst des 18. und 19. Jahrhunderts," p. 62.

- Frank Thadeusz, "Wie hässlich war der Alte Fritz?", Der Spiegel, no. 31, 26 July 2019.

- William Hogarth, Marriage A-la-Mode 4: The Toilette scene (1743-44). Detail: flautist.

- Krysmanski, "Does Hogarth depict Old Fritz truthfully with a crooked beak?," pp. 22-26.

- Françoise Forster-Hahn, "Adolph Menzel's 'Daguerreotypical' Image of Frederick the Great: A Liberal Bourgeois Interpretation of German History," Art Bulletin, 59, no. 2 (June 1977), pp. 242–261.

- Kathrin Maurer, "Franz Kugler and Adolph Menzel's History of Frederick the Great (1842)," in Visualizing the Past: The Power of the Image in German Historicism (Berlin and Boston: De Gruyter, 2013), pp. 118–144

- Jost Hermand, Adolph Menzel: Das Flötenkonzert in Sanssouci: Ein realistisch geträumtes Preußenbild (Frankfurt am Main: Fischer Taschenbuch, 1985).

- Several death masks hung on Menzel's studio wall, including that of the Prussian king. See Gisela Hopp, "Menzels 'Atelierwand' als Bildträger von Gedanken über Kriegsnot und Machtmissbrauch," Jahrbuch der Berliner Museen, 41 (1999), supplement, pp. 131–138.

- "Category:Statue of Friedrich II of Prussia in Szczecin - Wikimedia Commons". commons.wikimedia.org.

- Christian Daniel Rauch, Equestrian statue of Frederick the Great (1851).

Bibliography

- Helmut Börsch-Supan, “Friedrich der Große im zeitgenössischen Bildnis,” in Oswald Hauser (ed.), Friedrich der Grosse in seiner Zeit (Cologne and Vienna: Böhlau, 1987), pp. 255–270.

- Edwin von Campe, Die graphischen Porträts Friedrichs des Großen aus seiner Zeit und ihre Vorbilder (Munich: Bruckmann, 1958).

- Paul Dehnert, “Daniel Chodowiecki und der König”, Jahrbuch Preussischer Kulturbesitz, 14 (1977), 307–319.

- Françoise Forster-Hahn, “Adolph Menzel’s ‘Daguerreotypical’ Image of Frederick the Great: A Liberal Bourgeois Interpretation of German History,” Art Bulletin, 59, no. 2 (June 1977), pp. 242–261.

- Gunther Hahn and Alfred Kernd’l, Friedrich der Grosse im Münzbildnis seiner Zeit (Frankfurt am Main: Ullstein Verlag; Berlin: Propyläen Verlag, 1986).

- Arnold Hildebrand, Das Bildnis Friedrichs des Großen: Zeitgenössische Darstellungen, 2nd edition (Berlin: Nibelungen-Verlag, 1942).

- Saskia Hüneke, “Friedrich der Grosse in der Bildhauerkunst des 18. und 19. Jahrhunderts,” Jahrbuch/Stiftung Preußische Schlösser und Gärten Berlin-Brandenburg, 2 (1997–1998) (Berlin: Akademie-Verlag, 2001), pp. 59–91.

- Andrea M. Kluxen, Bild eines Königs: Friedrich der Große in der Graphik (Limburg/Lahn: C. A. Starke, 1986).

- Hubertus Kohle, Adolph Menzels Friedrich-Bilder: Theorie und Praxis der Geschichtsmalerei im Berlin der 1850er Jahre (Munich: Deutscher Kunstverlag, 2001).

- Bernd Krysmanski, Does Hogarth Depict Old Fritz Truthfully with a Crooked Beak? – The Pictures Familiar to Us from Pesne to Menzel Don’t Show This, ART-dok (University of Heidelberg: arthistoricum.net, 2022). doi:10.11588/artdok.00008019

- Frauke Mankartz, “Die Marke Friedrich: Der preußische König im zeitgenössischen Bild,” in Friederisiko: Friedrich der Große, exh. cat., Stiftung Preußische Schlösser und Gärten Berlin-Brandenburg, 2 vols (Munich: Hirmer, 2012), Die Ausstellung, pp. 204–221.

- Rainer Michaelis, “Friedrich der Große im Spiegel der Werke des Daniel Nikolaus Chodowiecki,” in Friederisiko: Friedrich der Große, exh. cat., Stiftung Preußische Schlösser und Gärten Berlin-Brandenburg, 2 vols (Munich: Hirmer, 2012), Die Essays, pp. 262–271.

- Martin Schieder, “Die auratische Abwesenheit des Königs: Zum schwierigen Umgang Friedrichs des Großen mit dem eigenen Bildnis,” in Bernd Sösemann/Gregor Vogt-Spira (eds.), Friedrich der Große in Europa: Geschichte einer wechselvollen Beziehung, 2 vols (Stuttgart: Franz Steiner Verlag, 2012), vol. 1, pp. 325–338.

- Paul Seidel, “Die Bildnisse Friedrichs des Großen,” Hohenzollern-Jahrbuch, 1 (1897), pp. 87–112.

- Paul Seidel, Friedrich der Grosse und die bildende Kunst (Leipzig and Berlin: Giesecke & Devrient, 1922).

External links

- Prussian Palaces and Gardens Foundation Berlin-Brandenburg: Images of Frederick

- University of Oxford: Portraits of Frederick

- Frederick II - Modest appearance. Sir Christopher Clark about Charles Amédée van Loo’s Portrait of King Frederick II of Prussia

- GetArchive: Portrait Paintings Of Friedrich Ii Of Prussia

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)