Post-acute infection syndrome

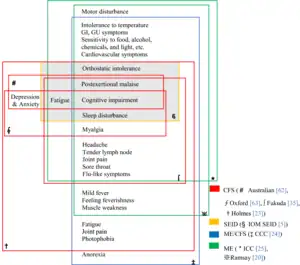

Post-acute infection syndromes (PAISs) or post-active phase of infection syndromes[1] are a group of medical conditions characterized by chronic illness triggered by an infection. They are sometimes referred to as infection-associated chronic illnesses as well.[2] While it is commonly assumed that people either recover or die from infections, illness is a possible outcome as well.[3] Examples include long COVID (post-acute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection, PASC), chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS), and post-Ebola virus syndrome.[3] Common symptoms include post-exertional malaise (PEM), severe fatigue, neurocognitive symptoms, flu-like symptoms, and pain. The pathology of most of these conditions is not understood and management is generally symptomatic.

Classification

PAIS is a broad term describing conditions triggered by various infections, including long COVID, ME/CFS, post-Ebola virus syndrome, post-dengue fatigue syndrome, post-polio syndrome, post-SARS syndrome, post-chikungunya disease, Q fever fatigue syndrome, post-treatment Lyme disease syndrome, and symptoms observed after other infections lacking a specific name.[3][4] Other better-understood sequela of infections include multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C), delayed acute encephalitis (a rare sequela of measles), and subacute sclerosing panencephalitis. ME/CFS has similar symptoms, and usually, but not always, has an apparent infectious trigger.[3]

Many of these conditions, together with multiple sclerosis, are also sometimes categorized as infection-associated chronic illnesses.[2]

Causes

.jpg.webp)

Pathogens associated with PAISs include SARS-CoV-2 (causing COVID-19), Ebolavirus, Dengue virus, poliovirus, SARS-CoV-1 (causing SARS), Chikungunya virus, Epstein–Barr virus (EBV), West Nile virus (WNV), Ross River virus (RRV), Coxsackie B, influenza A virus subtype H1N1, varicella zoster virus (VZV), Coxiella burnetii, Borrelia, and Giardia. However, the strength of evidence associating these pathogens with chronic illness varies.[3]

Mechanism

The pathology of post-acute infections syndromes is not understood. The commonality in symptoms between illnesses may point to a common pathology.[3] Major hypotheses include persistence of the original pathogen or its remnants, autoimmunity, chronic inflammation, reactivation of other latent infections, microbiome dysbiosis, or damage to organs, which may include the lungs, brain, kidneys, heart, or blood vessels.[3][4]

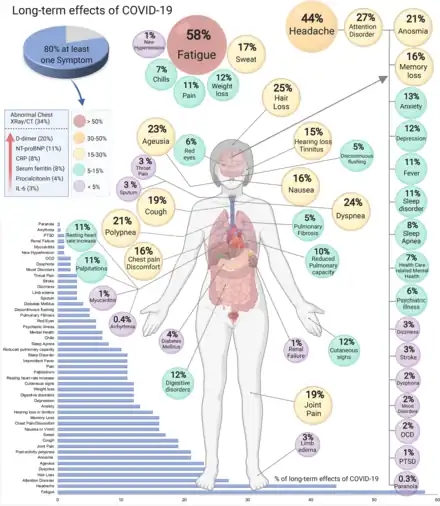

Symptoms

PAIS symptoms are broadly similar despite diverse triggers. Common symptoms include post-exertional malaise, severe fatigue, neurocognitive and sensory symptoms, flu-like symptoms, unrefreshing sleep, muscle pain, and joint pain. Other nonspecific symptoms may be present and vary among affected people.[3] Some syndromes have specific symptoms. For example, eye problems are common in post-Ebola virus syndrome, and profound weakness is seen in post-polio syndrome and post-West Nile fevers.[3]

Symptoms can be severe and debilitating, resulting in lowered quality of life or inability to work.[3]

Diagnosis

Diagnostic criteria vary among illnesses, and have at times been the subject of intense debate.[3] For example, several definitions of ME/CFS have been in use.[3]

Prognosis

Some people with PAISs recover over time, but others remain ill for years or decades. Many studies have shown that symptoms can continue for at least several years, after which the study concludes. Studies of PTLDS ran longer and found increased rates of symptoms for up to 27 years.[3]

Epidemiology

Data on epidemiology is limited by the lack of large, rigorous studies; and rates vary by infection. Mononucleosis is among the best studied, and available studies found that 7-9% had persistent symptoms 12 months after infection, and 4% had serious symptoms after 2 years. The British Office of National Statistics data on long COVID say that about 10% of people who had COVID-19 self-reported long COVID 6 months after infection, and about 7% reported long COVID with activity limitations. An Australian study of EBV, C. burnetii, and Ross River Virus found that 11% of participants met the criteria for ME/CFS at 6 months. Around 10-20% of people with SARS also experienced long-term effects.[3]

History

While PAISs are not new, the COVID-19 pandemic and the emergence of long COVID brought them increased attention.[3]

Society and culture

PAISs cause a significant disease burden, but have received relatively little attention from scientists, potentially delaying the discovery of causes, diagnostic tests, and treatments.[3][6] Many doctors are also unfamiliar with them, and may fail to take symptoms seriously.[7][4]

Research

PAISs may have a common cause, and different hypotheses are being studied.[4] Long COVID has increased the overall pace of research.[4] Yale School of Medicine operates a research center, founded in 2023, that focuses on PAISs called the Center for Infection & Immunity.[8]

See also

- Postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome, sometimes triggered by an infection

References

- Bai NA, Richardson CS (September 2023). "Posttreatment Lyme disease syndrome and myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome: A systematic review and comparison of pathogenesis". Chronic Diseases and Translational Medicine. 9 (3): 183–190. doi:10.1002/cdt3.74. PMC 10497844. PMID 37711861.

- "Infection-Associated Chronic Illnesses (2023)". healthdata.gov. Retrieved 2023-09-26.

- Choutka, Jan; Jansari, Viraj; Hornig, Mady; Iwasaki, Akiko (2022). "Unexplained post-acute infection syndromes". Nature Medicine. 28 (5): 911–923. doi:10.1038/s41591-022-01810-6. ISSN 1546-170X.

- Owens, Brian (2022-09-21). "How "long covid" is shedding light on postviral syndromes". BMJ. 378: o2188. doi:10.1136/bmj.o2188. ISSN 1756-1833. PMID 36130797.

- "Toward a Common Research Agenda in Infection-Associated Chronic Illnesses: A Workshop to Examine Common, Overlapping Clinical and Biological Factors". National Academies. Retrieved 2023-08-31.

- The Lancet Regional Health – Europe (2022-11-01). "Long COVID: An opportunity to focus on post-acute infection syndromes". The Lancet Regional Health - Europe. 22: 100540. doi:10.1016/j.lanepe.2022.100540. ISSN 2666-7762. PMC 9823272. PMID 36624784.

- Steenblock, Charlotte; Walther, Romy; Tselmin, Sergey; Jarzebska, Natalia; Voit-Bak, Karin; Toepfner, Nicole; Siepmann, Timo; Passauer, Jens; Hugo, Christian; Wintermann, Gloria; Julius, Ulrich; Barbir, Mahmoud; Khan, Tina Z.; Puhan, Milo A.; Straube, Richard (2022). "Post COVID and Apheresis – Where are we Standing?". Hormone and Metabolic Research. 54 (11): 715–720. doi:10.1055/a-1945-9694. ISSN 0018-5043.

- Backman, Isabella. "Post-Acute Infection Syndromes Will Be the Focus of New YSM Center". medicine.yale.edu. Retrieved 2023-09-22.