Pratt–Yorke opinion

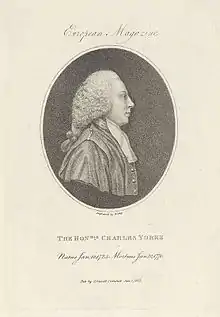

The Pratt-York opinion, also known as the Camden-Yorke opinion, was a 1757 official legal opinion that was issued jointly by Charles Pratt, 1st Earl Camden, the Attorney General for England and Wales, and Charles Yorke, the Solicitor General for England and Wales and former counsel to the East India Company, regarding the legality of land purchases by the British East India Company from the rulers of the princely states in British India.

In large part because of the opinion, India is one of the few common law jurisdiction that has rejected the doctrine of aboriginal title.[1][2][3][4][5][6]

Origin

The opinion was issued in response to a petition from the British East India Company.[7] The company had been involved in land disputes with regular army officers over both land acquired by purchase and land acquired by conquest.[8]

The opinion was reported on 24 December 1757.[9]

Text

The opinion began with the least controversial portion: territory gained by conquest was validly held by the company.[9] If in the course of the company's trade, the company acquired land by a defensive action, without the assistance of the regular army, it alone held title to those lands.[9]

The opinion went on to distinguish lands acquired by conquest from those acquired by treaty or negotiation.[9] In the former case, the Crown would acquire both sovereignty and title. In the latter case, the Crown would acquire sovereignty, but the company would acquire title.[9] Pratt and Yorke explained that in India, a land grant issued by the Crown was not a prerequisite for land titles to be valid.[7]

The opinion condoned direct purchases "from the Mogul or any of the Indian Princes, or governments."[7]

Chalmers' version

The following text of the opinion is given by George Chalmers in his 1814 text, Opinions of Eminent Lawyers:[10]

III. How far the king's subjects, who emigrate, carry with them the law of England: First, The common law; Second, The statute law.

First. As to the common law.

(1.) Mr. West's opinion on this subject in 1720.

The common law of England, is the common law of the plantations, and all statutes in affirmance of the common law, passed in England, antecedent to the settlement of a colony, are in force in that colony, unless there is some private act to the contrary, though no statutes, made since those settlements, are in force, unless the colonies are particularly mentioned. Let an Englishman go where he will, he carries as much of law and liberty with him, as the nature of things will bear.

(2.) The opinion of the attorney, and solicitor-general, Pratt, and Yorke, that the king's subjects carry with them the common law, wherever they may form settlements.

In respect to such places as have been, or shall be, acquired by treaty, or grant, from any of the Indian princes, or governments, your majesty's letters patent are not necessary; the property of the soil vesting in the grantees, by the Indian grants, subject only to your majesty's right of sovereignty over the settlements, as English settlements, and over the inhabitants, as English subjects, who carry with them your majesty's laws, wherever they form colonies, and receive your majesty's protection, by virtue of your royal charters.C. Pratt.

C. Yorke.

Effect in North America

Land speculators in North America who were opposed to the Royal Proclamation of 1763, which prohibited private purchases of land from Native Americans, circulated modified versions of the Pratt–Yorke opinion.[7][11][12] Mistranslated versions of the opinion appeared in North America around 1757 or 1773[7] and omitted all reference to the East India Company or the Mogul but instead referred simply to "Indian Princes or Governments."[7]

One reproduction of that version of the opinion can be found in the flyleaf of George Washington's 1783 diary.[7] The land speculator William Murray attempted, based on another copy, to persuade a British military commander to allow him to begin negotiations with Indians.[7]

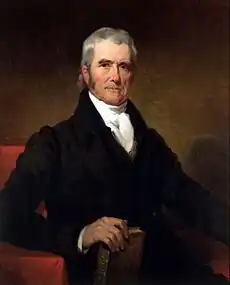

Chief Justice John Marshall, citing such a mistranscribed version, considered the relevance of the Pratt–Yorke opinion to the status of aboriginal title in the United States in Johnson v. McIntosh (1823):

The opinion of the Attorney and Solicitor General, Pratt and Yorke, have been adduced to prove, that, in the opinion of those great law officers, the Indian grant could convey a title to the soil without a patent emanating from the crown. The opinion of those persons would certainly be of great authority on such a question, and we were not a little surprised, when it was read, at the doctrine it seemed to advance. An opinion so contrary to the whole practice of the crown, and to the uniform opinions given on all other occasions by its great law officers, ought to be very explicit, and accompanied by the circumstances under which it was given, and to which it was applied, before we can be assured that it is properly understood. In a pamphlet, written for the purpose of asserting the Indian title, styled 'Plain Facts,' the same opinion is quoted, and is said to relate to purchases made in the East Indies. It is, of course, entirely inapplicable to purchases made in America. Chalmers, in whose collection this opinion is found, does not say to whom it applies; but there is reason to believe, that the author of Plain Facts is, in this respect, correct. The opinion commences thus:

'In respect to such places as have been, or shall be acquired, by treaty or grant, from any of the Indian princes or governments, your majesty's letters patent are not necessary.' The words 'princes or governments', are usually applied to the East Indians, but not to those of North America. We speak of their sachems, their warriors, their chiefmen, their nations or tribes, not of their 'princes or governments.' The question on which the opinion was given, too, and to which it relates, was, whether the king's subjects carry with them the common law wherever they may form settlements. The opinion is given with a view to this point, and its object must be kept in mind while construing its expressions.[13]

Notes

- Freeman v. Fairie (1828) 1 Moo. IA 305.

- Vaje Singji Jorava Ssingji v Secretary of State for India (1924) L.R. 51 I.A. 357.

- Virendra Singh & Ors v. The State of Uttar Pradesh [1954] INSC 55.

- Vinod Kumar Shantilal Gosalia v. Gangadhar Narsingdas Agarwal & Ors [1981] INSC 150.

- Sardar Govindrao & Ors v. State of Madhya Pradesh & Ors [1982] INSC 52.

- R.C. Poudyal & Anr. v. Union of India & Ors [1993] INSC 77.

- Banner, 2005, pp. 102–03.

- Bowen, 2002, p. 53.

- Bowen, 2002, p. 54.

- Chalmers, 1815, pp. 194–95.

- Sosin, 1965, pp. 229–35, 259–67.

- Gipson, 1936, pp. 487–88.

- Johnson v. McIntosh, 21 U.S. (8 Wheat.) 543, 599–600 (1823).

References

- Stuart Banner. 2005. How the Indians Lost Their Land: Law and Power on the Frontier. Belknap, Harvard University Press.

- H. V. Bowen. 2002. Revenue and Reform: The Indian Problem in British Politics 1757–1773. Cambridge University Press.

- Lawrence Henry Gipson. 1936. The British Empire Before the American Revolution: The rumbling of the coming storm, 1766–1770. Caxton Printers.

- J.M. Sosin. 1965. Whitehall and the Wilderness: The Middle West in British Colonial Policy 1760–1775. Lincoln, Nebraska.

- Copies of opinion

- Chalmers, George (1814). Opinions of Eminent Lawyers on Various Points of English Jurisprudence Chiefly Concerning the Colonies, Fisheries, and Commerce of Great Britain Collected, and Digested, from the Originals, in the Board of Trade, and Other Depositories. Reed and Hunter. pp. 194–195.

- S. Lambert (ed.). 1975. House of Commons Sessional Papers of the Eighteenth Century (147 vols.). Wilmington, Delaware. Vol. XXVI, item 1.

.jpg.webp)