Christian prayer

Christian prayer is an important activity in Christianity, and there are several different forms used for this practice.[1]

| Part of a series on |

| Christianity |

|---|

|

Christian prayers are diverse: they can be completely spontaneous, or read entirely from a text, such as from a breviary, which contains the canonical hours that are said at fixed prayer times. While praying, certain gestures usually accompany the prayers, including folding one's hands, bowing one's head, kneeling (often in the kneeler of a pew in corporate worship or in the kneeler of a prie-dieu in private worship), and prostration.

The most common prayer among Christians is the "Lord's Prayer", which according to the gospel accounts (e.g. Matthew 6:9-13) is how Jesus taught his disciples to pray.[2] The injunction for Christians to pray the Lord's prayer thrice daily was given in Didache 8, 2 f.,[3][4] which, in turn, was influenced by the Jewish practice of praying thrice daily found in the Old Testament, specifically in Psalm 55:17, which suggests "evening and morning and at noon", and Daniel 6:10, in which the prophet Daniel prays thrice a day.[3][4][5] The early Christians thus came to recite the Lord's Prayer thrice a day at 9 am, 12 pm, and 3 pm, supplanting the former Amidah predominant in the Hebrew tradition;[6][7][8] as such, in Christianity, many Lutheran and Anglican churches ring their church bells from belltowers three times a day: in the morning, at noon and in the evening summoning the Christian faithful to recite the Lord’s Prayer.[9][10][11]

From the time of the early Church, the practice of seven fixed prayer times have been taught; in Apostolic Tradition, Hippolytus instructed Christians to pray seven times a day "on rising, at the lighting of the evening lamp, at bedtime, at midnight" and "the third, sixth and ninth hours of the day, being hours associated with Christ's Passion."[12][13][14][15] Oriental Orthodox Christians, such as Copts and Indians, use a breviary such as the Agpeya and Shehimo to pray the canonical hours seven times a day at fixed prayer times while facing in the eastward direction, in anticipation of the Second Coming of Jesus; this Christian practice has its roots in Psalm 119:164, in which the prophet David prays to God seven times a day.[16][17] Church bells enjoin Christians to pray at these hours.[18] Before praying, they wash their hands and face in order to be clean before and present their best to God; shoes are removed in order to acknowledge that one is offering prayer before a holy God.[19][20] In these Christian denominations, and in many others as well, it is customary for women to wear a Christian headcovering when praying.[21][22] Many Christians have historically hung a Christian cross on the eastern wall of their houses to indicate the eastward direction of prayer during these seven prayer times.[23][12][24]

There are two basic settings for Christian prayer: corporate (or public) and private. Corporate prayer includes prayer shared within the worship setting or other public places, especially on the Lord's Day on which many Christian assemble collectively. These prayers can be formal written prayers, such as the liturgies contained in the Lutheran Service Book and Book of Common Prayer, as well as informal ejaculatory prayers or extemporaneous prayers, such as those offered in Methodist camp meetings. Private prayer occurs with the individual praying either silently or aloud within the home setting; the use of a daily devotional and prayer book in the private prayer life of a Christian is common. In Western Christianity, the prie-dieu has been historically used for the purpose of private prayer and many Christian homes possess home altars in the area where these are placed.[25][26] In Eastern Christianity, believers often keep icon corners at which they pray, which are on the eastern wall of the house.[27] Among Old Ritualists, a prayer rug known as a Podruchnik is used to keep one's face and hands clean during prostrations, as these parts of the body are used to make the sign of the cross.[28] Spontaneous prayer in Christianity, often done in private settings, follows the basic form of adoration, contrition, thanksgiving and supplication, abbreviated as A.C.T.S.[29]

Historical development

New Testament

Prayer in the New Testament is presented as a positive command (Colossians 4:2; 1 Thessalonians 5:17). The people of God are challenged to include prayer in their everyday life, even in the busy struggles of marriage (1 Corinthians 7:5) as it is thought to bring the faithful closer to God. Throughout the New Testament, prayer is shown to be God's appointed method by which the faithful obtain what he has to bestow (Matthew 7:7–11; Matthew 9:24–29; Luke 11:13). Prayer, according to the Book of Acts, can be seen at the first moments of the church (Acts 3:1). The apostles regarded prayer as an essential part of their lives (Acts 6:4; Romans 1:9; Colossians 1:9). As such, the apostles frequently incorporated verses from Psalms into their writings. Romans 3:10–18 for example is borrowed from Psalm 14:1–3 and other psalms.

Lengthy passages of the New Testament are prayers or canticles (see also the Book of Odes), such as the prayer for forgiveness (Mark 11:25–26), the Lord's Prayer, the Magnificat (Luke 1:46–55), the Benedictus (Luke 1:68–79), Jesus' prayer to the one true God (John 17), exclamations such as, "Praise be to the God and Father of our Lord Jesus Christ" (Ephesians 1:3–14), the Believers' Prayer (Acts 4:23–31), "may this cup be taken from me" (Matthew 26:36–44), "Pray that you will not fall into temptation" (Luke 22:39–46), Stephen's Prayer (Acts 7:59–60), Simon Magus' Prayer (Acts 8:24), "pray that we may be delivered from wicked and evil men" (2 Thessalonians 3:1–2), and Maranatha (1 Corinthians 16:22).

Early Christianity

Prayer and the reading of Scripture were important elements of Early Christianity. In the early Church worship was inseparable from doctrine as reflected in the statement: lex orandi, lex credendi, i.e. the law of belief is the law of prayer.[30] Early Christian liturgies highlight the importance of prayer.[31]

The Lord's Prayer was an essential element in the meetings held by the very early Christians, and it was spread by them as they preached Christianity in new lands.[32] Over time, a variety of prayers were developed as the production of early Christian literature intensified.[33]

As early as the 2nd century, Christians indicated the eastward direction of prayer by placing a Christian cross on the eastern wall of their house or church, prostrating in front of it as they prayed at seven fixed prayer times.[12][34][26]

By the 3rd century Origen had advanced the view of "Scripture as a sacrament".[35] Origen's methods of interpreting Scripture and praying on them were learned by Ambrose of Milan, who towards the end of the 4th century taught them to Augustine of Hippo, thereby introducing them into the monastic traditions of the Western Church thereafter.[36][37]

Early models of Christian monastic life emerged in the 4th century, as the Desert Fathers began to seek God in the deserts of Palestine and Egypt.[38][39] These early communities gave rise to the tradition of a Christian life of "constant prayer" in a monastic setting which eventually resulted in meditative practices in the Eastern Church during the Byzantine period.[39]

Meditation in the Middle Ages

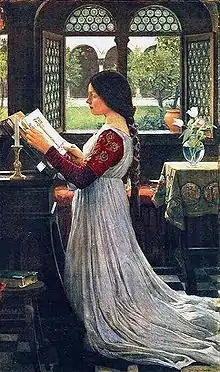

During the Middle Ages, the monastic traditions of both Western and Eastern Christianity moved beyond vocal prayer to Christian meditation. These progressions resulted in two distinct and different meditative practices: Lectio Divina in the West and hesychasm in the East. Hesychasm involves the repetition of the Jesus Prayer, but Lectio Divina uses different Scripture passages at different times and although a passage may be repeated a few times, Lectio Divina is not repetitive in nature.[39][40]

In the Western Church, by the 6th century, Benedict of Nursia and Pope Gregory I had initiated the formal methods of scriptural prayer called Lectio Divina.[41] With the motto Ora et labora (i.e. pray and work), daily life in a Benedictine monastery consisted of three elements: liturgical prayer, manual labor and Lectio Divina, a quiet prayerful reading of the Bible.[42] This slow and thoughtful reading of Scripture, and the ensuing pondering of its meaning, was their meditation.[43]

Early in the 12th century, Bernard of Clairvaux was instrumental in re-emphasizing the importance of Lectio Divina within the Cistercian order.[44] Bernard also emphasized the role of the Holy Spirit in contemplative prayer and compared it to a kiss by the Eternal Father which allows a union with God.[45]

The progression from Bible reading, to meditation, to loving regard for God, was first formally described by Guigo II, a Carthusian monk who died late in the 12th century.[46] Guigo II's book The Ladder of Monks is considered the first description of methodical prayer in the western mystical tradition.[47]

In Eastern Christianity, the monastic traditions of "constant prayer" that traced back to the Desert Fathers and Evagrius Pontikos established the practice of hesychasm and influenced John Climacus' book The Ladder of Divine Ascent by the 7th century.[48] These meditative prayers were promoted and supported by Gregory Palamas in the 14th century.[49][39]

Contemplative prayer

In the Western Church, during the 15th century, reforms of the clergy and monastic settings were undertaken by the two Venetians, Lorenzo Giustiniani and Louis Barbo. Both men considered methodical prayer and meditation as essential tools for the reforms they were undertaking.[50] Barbo, who died in 1443, wrote a treatise on prayer titled Forma orationis et meditionis otherwise known as Modus meditandi. He described three types of prayer; vocal prayer, best suited for beginners; meditation, oriented towards those who are more advanced; and contemplation as the highest form of prayer, only obtainable after the meditation stage. Based on the request of Pope Eugene IV, Barbo introduced these methods to Valladolid, Spain and by the end of the 15th century they were being used at the abbey of Montserrat. These methods then influenced Garcias de Cisneros, who in turn influenced Ignatius of Loyola.[51][52]

The Eastern Orthodox Church has a similar three level hierarchy of prayer.[53][54] The first level prayer is again vocal prayer, the second level is meditation (also called "inward prayer" or "discursive prayer") and the third level is contemplative prayer in which a much closer relationship with God is cultivated.[53]

Types of prayer

Christian prayer can be divided into different categories, varying by denomination and tradition. Over time, theologians have studied different types of prayer. For example, theologian Gilbert W. Stafford divided prayer into eight different types based on New Testament scripture.[55] Interpretations of prayer in the New Testament and the Christian faith as a whole widely vary, leading to the practice of different types of prayer.

Daily prayer

Canonical hours

In Apostolic Tradition, Hippolytus instructed Christians to pray seven times a day "on rising, at the lighting of the evening lamp, at bedtime, at midnight" and "the third, sixth and ninth hours of the day, being hours associated with Christ's Passion."[12][13][14][15]

Eastern Christians of the Alexandrian Rite and Syriac Rite, use a breviary such as the Agpeya and Shehimo to pray the canonical hours seven times a day at fixed prayer times while facing in the eastward direction, in anticipation of the Second Coming of Jesus; this Christian practice has its roots in Psalm 118:164, in which the prophet David is described as praying to God seven times a day.[56][16][17] These Christians incorporate prostrations in their prayers, "prostrating three times in the name of the Trinity; at the end of each Psalm … while saying the ‘Alleluia’; and multiple times during the more than forty Kyrie eleisons" as with the Copts and thrice during the Qauma prayer, at the words "Crucified for us, Have mercy on us!", thrice during the recitation of the Nicene Creed at the words "And was incarnate of the Holy Spirit...", "And was crucified for us...", & "And on the third day rose again...", as well as thrice during the Prayer of the Cherubim while praying the words "Blessed is the glory of the Lord, from His place forever!" as with the Indians.[57][20] Before praying, Oriental Christians wash their hands, face and feet out of respect for God; shoes are removed in order to acknowledge that one is offering prayer before a holy God.[58][20][19][59] In this Christian denomination, and in many others as well, it is customary for women to wear a Christian headcovering when praying.[21][22]

In the Lutheran Churches, the canonical hours are contained in breviaries such as The Brotherhood Prayer Book and For All the Saints: A Prayer Book for and by the Church, while in the Roman Catholic Church they are known as the Liturgy of the Hours.[60][61] The Methodist tradition has emphasized the praying of the canonical hours as an "essential practice" in being a disciple of Jesus.[62]

Lord's Prayer

The injunction for Christians to pray the Lord's Prayer thrice daily was given in Didache 8, 2 f.,[3][4] which, in turn, was influenced by the Jewish practice of praying thrice daily found in the Old Testament, specifically in Psalm 55:17, which suggests "evening and morning and at noon", and Daniel 6:10, in which the prophet Daniel prays thrice a day.[3][4][5] The early Christians came to pray the Lord's Prayer thrice a day at 9 am, 12 pm and 3 pm, supplanting the former Amidah predominant in the Hebrew tradition.[8][6] As such, in Christianity, many Lutheran and Anglican churches ring their church bells from belltowers three times a day, summoning the Christian faithful to recite the Lord’s Prayer.[9][10][7]

Sign of the Cross

The sign of the cross is a short prayer used daily by many Christians, especially those of the Catholic, Lutheran, Oriental Orthodox, Eastern Orthodox, Methodist and Anglican traditions apart from its daily use in private prayer, it is widely used in corporate prayer by these Christian denominations. The Small Catechism, a catechism used in the Lutheran Churches, instructs believers "to make the sign of the cross at both the beginning and the end of the day as a beginning to daily prayers."[63] It specifically instructs Christians: "When you get out of bed, bless yourself with the holy cross and say ‘In the name of God, the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit. Amen.’"[63]

Mealtime prayer

Christians often pray to ask God to thank Him for and bless their food before consuming it at the time of eating meals, such as supper.[64] These prayers vary per Christian denomination, e.g. the common table prayer is used by communicants of the Lutheran Churches and the Moravian Church.

Seasonal prayer

Many denominations use specific prayers geared to the season of the Christian Liturgical Year, such as Advent, Christmas, Lent and Easter. Some of these prayers are found in the Roman Breviary, the Liturgy of the Hours, the Orthodox Book of Needs, Evangelical Lutheran Worship, and the Anglican Book of Common Prayer.

In the seasons of Advent and Lent, many Christians add the reading of a daily devotional to their prayer life; items that aid in prayer, such as an Advent wreath or Lenten calendar are unique to those seasons of the Church Year.

Intercession of saints

The ancient church, in both Eastern Christianity and Western Christianity, developed a tradition of asking for the intercession of (deceased) saints, and this remains the practice of most Eastern Orthodox, Oriental Orthodox, Roman Catholic, as well as some Lutheran and Anglican churches. Most of the Reformed Churches however rejected this practice, largely on the basis of belief in the sole mediatorship of Christ.[65]

Meditation and contemplative prayer

A broad, three stage characterization of prayer begins with vocal prayer, then moves on to a more structured form in terms of meditation, then reaches the multiple layers of contemplation,[66][67] or intercession.

Christian meditation is a structured attempt to get in touch with and deliberately reflect upon the revelations of God.[68] The word meditation comes from the Latin word meditārī, which has a range of meanings including to reflect on, to study and to practice. Christian meditation is the process of deliberately focusing on specific thoughts (such as a bible passage) and reflecting on their meaning in the context of the love of God.[69]

Christian meditation aims to heighten the personal relationship based on the love of God that marks Christian communion.[70][71]

At times there may be no clear-cut boundary between Christian meditation and Christian contemplation, and they overlap. Meditation serves as a foundation on which the contemplative life stands, the practice by which someone begins the state of contemplation.[72] In contemplative prayer, this activity is curtailed, so that contemplation has been described as "a gaze of faith", "a silent love".[73]

Meditation and contemplation on the life of Jesus in the New Testament are components of the rosary[74] and are central to spiritual retreats and to the prayer that grows out of these retreats.[75]

Intercessory prayer

This kind of prayer involves the believer taking the role of an intercessor, praying on behalf of another individual, group or community, or even a nation.

Ejaculatory prayer

Ejaculatory prayer is the use of very brief exclamations. Saint Augustine remarked that the Egyptian Christians who withdrew to a solitary life "are said to say frequent prayers, but very brief ones that are tossed off as in a rush, so that a vigilant and keen intention, which is very necessary for one who prays, may not fade away and grow dull over longer periods".[76]

Examples of such prayers are given in the old Raccolta under the numbers 19, 20, 38, 57, 59, 63, 77, 82, 83, 133, 154, 166, 181.[77]

They are also known as aspirations, invocations or exclamations and include the Jesus Prayer.[78]

Johnson's Dictionary defined "ejaculation" as "a short prayer darted out occasionally, without solemn retirement".[79] Such pious ejaculations are part also of the liturgy of the Church of England.[80]

Listening prayer

Listening prayer is a traditional form of Christian prayer.

Listening prayer requires those praying to sit in silence in the presence of God. It can, but need not, be preceded by a scripture reading. This method of prayer is most fully explored in the works of Catholic Saints such as St.Teresa of Avilla.

Child's prayer

A Christian child's prayer is typically short, rhyming, or has a memorable tune. It is usually said before bedtime, to give thanks for a meal, or as a nursery rhyme. Many of these prayers are either quotes from the Bible, or set traditional texts.

Prayer books and tools

Prayer books as well as tools such as prayer beads such as chaplets are used by Christians. Images and icons are also associated with prayers in some Christian denominations.

There is no one prayerbook containing a set liturgy used by all Christians; however many Christian denominations have their own local prayerbooks, for example:

- Agpeya also known as the Book of Hours for the Coptic Orthodox Christians of Egypt. The book is a collection of texts from the gospels, epistles and most importantly the book of Psalms as well as ancient prayers of the Church Fathers; seven main prayers are distributed over the seven fixed prayer times of the day with relevant texts about every particular hour from the Bible.

- Agenda, name for book for liturgies, especially in Lutheran Church.

- Book of Common Prayer (the traditional Anglican prayer book, still in use or modified by the constituent churches of the Anglican Communion, and one of the most influential prayerbooks in the English language)

- Shehimo, the breviary of the Indian Orthodoxy containing the canonical hours for the seven fixed prayer times of the day[57]

- The Book of Psalms

- The Raccolta book of indulgenced prayers for Catholics

- The Roman Breviary (Traditional Roman Catholic Monastic Hours)

References and footnotes

- Philip Zaleski, Carol Zaleski (2005). Prayer: A History. Houghton Mifflin Books. ISBN 0-618-15288-1.

- Geldart, Anne (1999). Examining Religions: Christianity Foundation Edition. p. 108. ISBN 0-435-30324-4.

- Gerhard Kittel; Gerhard Friedrich (1972). Theological Dictionary of the New Testament, Volume 8. William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company. p. 224. ISBN 9780802822505. Retrieved 26 October 2012.

The praying of the Lord's Prayer three times a day in Did., 8, 2 f. is connected with the Jewish practice --> 218, 3 ff.; II, 801, 16 ff.; the altering of other Jewish customs is demanded in the context.

- Roger T. Beckwith (2005). Calendar, Chronology, and Worship: Studies in Ancient Judaism and Early Christianity. Brill Publishers. p. 193. ISBN 9004146032. Retrieved 26 October 2012.

The Church had now two hours of prayer, observed individually on weekdays and corporately on Sundays – yet the Old Testament spoke of three daily hours of prayer, and the Church itself had been saying the Lord's Prayer three times a day.

- James F White (1 September 2010). Introduction to Christian Worship 3rd Edition: Revised and Enlarged. Abingdon Press. ISBN 9781426722851. Retrieved 12 October 2012.

Late in the first century or early in the second, the Didache advised Christians to pray the Lord's prayer three times a day. Others sought disciplines in the Bible itself as ways to make the scriptural injunction to "pray without ceasing" (1 Thess. 5:17) practical. Psalm 55:17 suggested "evening and morning and at noon," and Daniel prayed three times a day (Dan. 6:10).

- Catechism Of The Catholic Church. Continuum International Publishing Group. 1999. ISBN 0-860-12324-3. Retrieved 2 September 2014.

Late in the first century or early in the second, the Didache advised Christians to pray the Lord's prayer three times a day. Others sought disciplines in the Bible itself as ways to make the scriptural injunction to "pray without ceasing" (1 Thess. 5:17) practical. Psalm 55:17 suggested "evening and morning and at noon," and Daniel prayed three times a day (Dan. 6:10).

- Matthew: A Shorter Commentary. Continuum International Publishing Group. 2005. ISBN 9780567082497. Retrieved 16 August 2012.

Moreover, the central portion of the Eighteen Benedictions, just like the Lord's Prayer, falls into two distinct parts (in the first half the petitions are for the individuals, in the second half for the nation); and early Christian tradition instructs believers to say the Lord's Prayer three times a day (Did. 8.3) while standing (Apost. const. 7.24), which precisely parallels what the rabbis demanded for the Eighteen Benedictions.

- Beckwith, Roger T. (2005). Calendar, Chronology And Worship: Studies in Ancient Judaism And Early Christianity. BRILL. ISBN 978-90-04-14603-7.

So three minor hours of prayer were developed, at the third, sixth and ninth hours, which, as Dugmore points out, were ordinary divisions of the day for worldly affairs, and the Lord's Prayer was transferred to those hours.

- George Herbert Dryer (1897). History of the Christian Church. Curts & Jennings.

…every church-bell in Christendom to be tolled three times a day, and all Christians to repeat Pater Nosters (The Lord's Prayer)

- Joan Huyser-Honig (2006). "Uncovering the Blessing of Fixed-Hour Prayer". Calvin Institute of Christian Worship.

Early Christians prayed the Lord's Prayer three times a day. Medieval church bells called people to common prayer.

- "Church bells". Wisconsin Evangelical Lutheran Synod. 25 July 2017. Retrieved 8 August 2020.

- Danielou, Jean (2016). Origen. Wipf and Stock Publishers. p. 29. ISBN 978-1-4982-9023-4.

Peterson quotes a passage from the Acts of Hipparchus and Philotheus: "In Hipparchus's house there was a specially decorated room and a cross was painted on the east wall of it. There before the image of the cross, they used to pray seven times a day ... with their faces turned to the east." It is easy to see the importance of this passage when you compare it with what Origen says. The custom of turning towards the rising sun when praying had been replaced by the habit of turning towards the east wall. This we find in Origen. From the other passage we see that a cross had been painted on the wall to show which was the east. Hence the origin of the practice of hanging crucifixes on the walls of the private rooms in Christian houses. We know too that signs were put up in the Jewish synagogues to show the direction of Jerusalem, because the Jews turned that way when they said their prayers. The question of the proper way to face for prayer has always been of great importance in the East. It is worth remembering that Mohammedans pray with their faces turned towards Mecca and that one reason for the condemnation of Al Hallaj, the Mohammedan martyr, was that he refused to conform to this practice.

- Henry Chadwick (1993). The Early Church. Penguin. ISBN 978-1-101-16042-8.

Hippolytus in the Apostolic Tradition directed that Christians should pray seven times a day - on rising, at the lighting of the evening lamp, at bedtime, at midnight, and also, if at home, at the third, sixth and ninth hours of the day, being hours associated with Christ's Passion. Prayers at the third, sixth, and ninth hours are similarly mentioned by Tertullian, Cyprian, Clement of Alexandria and Origen, and must have been very widely practised. These prayers were commonly associated with private Bible reading in the family.

- Weitzman, M. P. (7 July 2005). The Syriac Version of the Old Testament. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-01746-6.

Clement of Alexandria noted that "some fix hours for prayer, such as the third, sixth and ninth" (Stromata 7:7). Tertullian commends these hours, because of their importance (see below) in the New Testament and because their number recalls the Trinity (De Oratione 25). These hours indeed appear as designated for prayer from the earliest days of the church. Peter prayed at the sixth hour, i.e. at noon (Acts 10:9). The ninth hour is called the "hour of prayer" (Acts 3:1). This was the hour when Cornelius prayed even as a "God-fearer" attached to the Jewish community, i.e. before his conversion to Christianity. it was also the hour of Jesus' final prayer (Matt. 27:46, Mark 15:34, Luke 22:44-46).

- Lössl, Josef (17 February 2010). The Early Church: History and Memory. A&C Black. p. 135. ISBN 978-0-567-16561-9.

Not only the content of early Christian prayer was rooted in Jewish tradition; its daily structure too initially followed a Jewish pattern, with prayer times in the early morning, at noon and in the evening. Later (in the course of the second century), this pattern combined with another one; namely prayer times in the evening, at midnight and in the morning. As a result seven 'hours of prayer' emerged, which later became the monastic 'hours' and are still treated as 'standard' prayer times in many churches today. They are roughly equivalent to midnight, 6 a.m., 9 a.m., noon, 3 p.m., 6 p.m. and 9 p.m. Prayer positions included prostration, kneeling and standing. ... Crosses made of wood or stone, or painted on walls or laid out as mosaics, were also in use, at first not directly as objections of veneration but in order to 'orientate' the direction of prayer (i.e. towards the east, Latin oriens).

- "Prayers of the Church". Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church. Retrieved 25 July 2020.

- "Why We Pray Facing East". Orthodox Prayer. Retrieved 25 July 2020.

- "What is the relationship between bells and the church? When and where did the tradition begin? Should bells ring in every church?". Coptic Orthodox Diocese of the Southern United States. 2020. Retrieved 8 August 2020.

- Mary Cecil, 2nd Baroness Amherst of Hackney (1906). A Sketch of Egyptian History from the Earliest Times to the Present Day. Methuen. p. 399.

Prayers 7 times a day are enjoined, and the most strict among the Copts recite one of more of the Psalms of David each time they pray. They always wash their hands and faces before devotions, and turn to the East.

- Kosloski, Philip (16 October 2017). "Did you know Muslims pray in a similar way to some Christians?". Aleteia. Retrieved 25 July 2020.

- Bercot, David. "Head Covering Through the Centuries". Scroll Publishing. Retrieved 28 April 2016.

- Duffner, Jordan Denari (13 February 2014). "Wait, I thought that was a Muslim thing?!". Commonweal. Retrieved 26 July 2020.

- "Sign of the Cross". Holy Apostolic Catholic Assyrian Church of the East - Archdiocese of Australia, New Zealand and Lebanon. Holy Apostolic Catholic Assyrian Church of the East - Archdiocese of Australia, New Zealand and Lebanon. Archived from the original on 14 April 2020. Retrieved 11 August 2020.

Inside their homes, a cross is placed on the eastern wall of the first room. If one sees a cross in a house and do not find a crucifix or pictures, it is almost certain that the particular family belongs to the Church of the East.

- Johnson, Maxwell E. (2016). Between Memory and Hope: Readings on the Liturgical Year. Liturgical Press. ISBN 978-0-8146-6282-3.

Because Christ was expected to come from the east, Christians at a very early date prayed facing that direction in order to show themselves ready for his appearing, and actually looking forward to the great event which would consummate the union with him already experienced in prayer. For the same reason the sign of the cross was frequently traced on the eastern wall of places of prayer, thereby indicating the direction of prayer, but also rendering the Lord's coming a present reality in the sign which heralds it. In other words, through the cross the anticipated eschatological appearance becomes parousia: presence. The joining of prayer with the eschatological presence of Christ, unseen to the eye but revealed in the cross, obviously underlies the widely attested practice of prostrating before the sacred wood while praying to him who hung upon it.

- "Home Altars". Eden Prairie: Immanuel Lutheran Church. Retrieved 25 July 2020.

- Storey, William G. (2004). A Prayer Book of Catholic Devotions: Praying the Seasons and Feasts of the Church Year. Loyola Press. ISBN 978-0-8294-2030-2.

Long before Christians built churches for public prayer, they worshipped daily in their homes. In order to orient their prayer (to orient means literally "to turn toward the east"), they painted or hung a cross on the east wall of their main room. This practice was in keeping with ancient Jewish tradition ("Look toward the east, O Jerusalem," Baruch 4:36); Christians turned in that direction when they prayed morning and evening and at other times. This expression of their undying belief in the coming again of Jesus was united to their conviction that the cross, "the sign of the Son of Man," would appear in the eastern heavens on his return (see Matthew 24:30). Building on that ancient custom, devout Catholics often have a home altar, shrine, or prayer corner containing a crucifix, religious pictures (icons), a Bible, holy water, lights, and flowers as a part of the essential furniture of a Christian home.

- Shoemaker, Caleb (5 December 2016). "Little Church Foundations: Icon Corner". Behind the Scenes. Ancient Faith Ministries. Retrieved 11 August 2020.

Identify a wall or corner in a main living area of your house. Preferably, your icons will be on an east wall so your family can be facing east–just like at Divine Liturgy–whenever you say your prayers together.

- Basenkov, Vladimir (10 June 2017). "Vladimir Basenkov. Getting To Know the Old Believers: How We Pray". Orthodox Christianity. Retrieved 25 July 2020.

- Cottrell, Stephen (2003). Praying Through Life: How to Pray in the Home, at Work and in the Family. Church House Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7151-4010-9.

- The Formation of Christian Doctrine by Malcolm B. Yarnell 2007 ISBN 0-8054-4046-1 page 147

- Introducing Early Christianity by Laurie Guy 2011 ISBN 0-8308-3942-9 page 203

- The Lord's Prayer in the Early Church by Frederic Henry Chase 2004 ISBN 1-59333-275-0 pages 13-15

- The Encyclopedia of Christian Literature, Volume 1 by George Thomas Kurian 2010 ISBN 0-8108-6987-X pages 135-138

- Kalleeny, Tony. "Why We Face the EAST". Orlando: St Mary and Archangel Michael Church. Retrieved 6 August 2020.

Christians in Syria as well, in the second century, would place the cross in the direction of the East towards which people in their homes or churches prayed.

- Reading to live: the evolving practice of Lectio divina by Raymond Studzinski 2010 ISBN 0-87907-231-8 pages 26-35

- Vatican website: Benedict XVI, General Audience 2 May 2007

- The Fathers of the church: from Clement of Rome to Augustine of Hippo by Pope Benedict XVI 2009 ISBN 0-8028-6459-7 page 100

- Christian spirituality: themes from the tradition by Lawrence S. Cunningham, Keith J. Egan 1996 ISBN 978-0-8091-3660-5 page 88-94

- Globalization of Hesychasm and the Jesus Prayer: Contesting Contemplation by Christopher D. L. Johnson 2010 ISBN 978-1-4411-2547-7 pages 31-38

- Reading with God: Lectio Divina by David Foster 2006 ISBN 0-8264-6084-4 page 44

- After Augustine: the meditative reader and the text by Brian Stock 2001 ISBN 0-8122-3602-5 page 105

- Christian Spirituality: A Historical Sketch by George Lane 2005 ISBN 0-8294-2081-9 page 20

- Holy Conversation: Spirituality for Worship by Jonathan Linman 2010 ISBN 0-8006-2130-1 pages 32-37

- Christian spirituality: themes from the tradition by Lawrence S. Cunningham, Keith J. Egan 1996 ISBN 978-0-8091-3660-5 pages 91-92

- The Holy Spirit by F. LeRon Shults, Andrea Hollingsworth 2008 ISBN 0-8028-2464-1 page 103

- Christian spirituality: themes from the tradition by Lawrence S. Cunningham, Keith J. Egan 1996 ISBN 978-0-8091-3660-5 pages 38-39

- An Anthology of Christian mysticism by Harvey D. Egan 1991 ISBN 0-8146-6012-6 pages 207-208

- Orthodox Church: Its Past and Its Role in the World Today by John Meyendorff 1981 ISBN 0-913836-81-8 page

- Browning, Robert (1992). The Byzantine Empire (Rev. ed.). Washington, D.C.: Catholic University of America Press. p. 238. ISBN 0-8132-0754-1.

- The church in Italy in the fifteenth century by Denys Hay 2002 ISBN 0-521-52191-2 page 76

- Christian spirituality in the Catholic tradition by Jordan Aumann 1985 Ignatius Press ISBN 0-89870-068-X page 180

- Catholic encyclopedia

- Orthodox prayer life: the interior way by Mattá al-Miskīn 2003 ISBN 0-88141-250-3 St Vladimir Press, "Chapter 2: Degrees of Prayer" pages 39-42

- The art of prayer: an Orthodox anthology by Igumen Chariton 1997 ISBN 0-571-19165-7 pages 63-65

- Gilbert W. Stafford, Theology for Disciples, (Anderson: Warner Press, 1996), 411–426.

- Richards, William Joseph (1908). The Indian Christians of St. Thomas: Otherwise Called the Syrian Christians of Malabar: a Sketch of Their History and an Account of Their Present Condition as Well as a Discussion of the Legend of St. Thomas. Bemrose. p. 98.

We are commanded to pray standing, with faces towards the East, for at the last Messiah is manifested in the East. 2. All Christians, on rising from sleep early in the morning, should wash the face and pray. 3. We are commanded to pray seven times, thus...

- Shehimo: Book of Common Prayer. Diocese of South-West America of the Malankara Orthodox Syrian Church. 2016. pp. 5, 7, 12.

- Smith, Bertha H. (1909). "The Bath as a Religious Rite among Mohammedans". Modern Sanitation. Standard Sanitary Mfg. Co. 7 (1).

The Copts, descendants of these ancient Egyptians, although Christians, have the custom of washing their hands and faces before prayer, and some also wash their feet.

- Bishop Brian J Kennedy, OSB. "Importance of the Prayer Rug". St. Finian Orthodox Abbey. Retrieved 25 July 2020.

- Benne, Robert (2003). Ordinary Saints: An Introduction to the Christian Life. Fortress Press. p. 53. ISBN 978-1-4514-1719-7.

- Mayes, Benjamin T. G. (5 September 2004). "Daily Prayer Books in the History of German and American Lutheranism" (PDF). Lutheran Liturgical Prayer Brotherhood. Retrieved 25 July 2020.

- "Praying the Hours of the Day: Recovering Daily Prayer". General Board of Discipleship. 6 May 2007. Retrieved 6 September 2020.

- "Why do Lutherans make the sign of the cross?" (PDF). Evangelical Lutheran Church in America. 2013. p. 2. Retrieved 25 July 2020.

- Pringle, Phil (2009). Inspired to Pray: The Art of Seeking God. Gospel Light Publications. p. 90. ISBN 978-0-8307-4811-2.

- Ferguson, S. B.; Packer, J. (1988). "Saints". New Dictionary of Theology. Downers Grove, IL: Intervarsity Press.

- Griffin, Emilie (2005). Simple Ways to Pray. p. 134. ISBN 0-7425-5084-2.

- "The Christian tradition comprises three major expressions of the life of prayer: vocal prayer, meditation, and contemplative prayer. They have in common the recollection of the heart" (Catechism of the Catholic Church, 2721).

- Zanzig, Thomas; Kielbasa, Marilyn (2000). Christian Meditation for Beginners. p. 7. ISBN 0-88489-361-8.

- Antonisamy, F. (2000). An introduction to Christian spirituality. pp. 76–77. ISBN 81-7109-429-5.

- Christian Meditation by Edmund P. Clowney, 1979 ISBN 1-57383-227-8 pages 12-13

- Fahlbusch, Erwin; Bromiley, Geoffrey William (2003). The encyclopedia of Christianity. Vol. 3. p. 488. ISBN 90-04-12654-6.

- al-Miskīn, Mattá (2003). Orthodox Prayer Life: The Interior Way. St Vladimir's Seminary Press. p. 56. ISBN 0-88141-250-3.

- "Contemplative prayer is the simple expression of the mystery of prayer. It is a gaze of faith fixed on Jesus, an attentiveness to the Word of God, a silent love. It achieves real union with the prayer of Christ to the extent that it makes us share in his mystery" (Catechism of the Catholic Church, 2724).

- "Rosarium Virginis Mariae on the Most Holy Rosary (October 16, 2002) | John Paul II".

- "Ignatian Contemplation: Imaginative Prayer - IgnatianSpirituality.com". Ignatian Spirituality. Retrieved 2020-09-12.

- Augustine, Letter 130, To Proba, paragraph 20

- The Raccolta: Index of prayers and pious works contained in this collection

- Stephen Beale, "Deepen Your Prayer Life Through Exclamations"

- Samuel Johnson, A Dictionary of the English Language, vol. 2]

- Matthew Hole, Practical discourses on the liturgy of the Church of England (London. William Pickering. 1837), p. 153

- Johann G. Roten, S.M. "Lutheran rosary". University of Dayton. Retrieved 12 August 2016.

Further reading

- Callan, Very Rev. Charles J. (1925). . Blessed be God; a complete Catholic prayer book. P. J. Kenedy & Sons.

- Carroll, James. Prayer from Where We Are. In series, Witness Book[s], 13, and also in Christian Experience Series. Dayton, Ohio: G.A. Pflaum, 1970.

- Daughters of Charity of St. Vincent de Paul. (1856). . St. Vincent's Manual. John Murphy & Co.

- Heiler, Friedrich (1997). Prayer: a study in the history and psychology of Religion. Oxyford: Oneworld Publications. ISBN 9781851681433.

- Kempis, Thomas A. (1908). . London: Kegan Paul.

- Moran, Rev. Patrick (1883). . Dublin: Browne & Nolan.

- . The catechism of the Council of Trent. Translated by James Donovan. Lucas Brothers. 1829.

External links

- Agpeya: Coptic Book of Hours (used for Daily Prayer in Oriental Orthodox Christianity)

- Daily Prayer (used in the Church of England, mother church of the Anglican Communion)

- St. Thomas Aquinas. "Prayers of St. Thomas Aquinas". liturgies.net. Archived from the original on February 2, 2013.

- St. Augustine of Hippo. "Prayers of St. Augustine of Hippo". villanova.edu. Archived from the original on 2018-10-01. Retrieved Oct 1, 2018.

- Matthew Henry. "A Method for Prayer (1710); the Protestant Book of Hours". mrmatthewhenry.com. Archived from the original on 2013-10-12. Retrieved 2013-11-12. (Free eBooks and audio books)

- "How to Pray for Your Church Using a Prayer Walk and Posted Prayer Notes". prayerideas.org. Sep 26, 2015. Archived from the original on February 27, 2017. Retrieved Oct 1, 2018.