Ottoman archives

The Ottoman archives are a collection of historical sources related to the Ottoman Empire and a total of 39 nations whose territories one time or the other were part of this Empire, including 19 nations in the Middle East, 11 in the EU and Balkans, three in the Caucasus, two in Central Asia, Cyprus, as well as the Republic of Turkey.

| Ottoman Archives | |

|---|---|

| Başbakanlık Osmanlı Arşivleri | |

| Location | Kağıthane , Istanbul, Turkey |

The main collection, in the Başbakanlık Osmanlı Arşivleri (The Prime Minister's Ottoman Archives) in Istanbul, holds the central State Archives (Devlet arşivleri).

After more than a century in the center of the old city, the Ottoman state archives were relocated in 2013 to the Kağıthane district of Istanbul.

History

The present collection contains a few documents from the earliest period up to the reign of Sultan Süleyman in the sixteenth century. The organization of these records as a modern archive began in 1847 with the establishment of Hazine-i Evrak.[1] The original building was located on the grounds of the grand vezir's offices in Gülhane and contained several main groups of documents: the records of the Imperial Council (Divan-i Hümayun) and the records of the grand vezir's office (Bab-i Ali), as well as the records of the financial departments (Maliye) and cadastral surveys (tapu tahrir defteri). Mustafa Reşid Paşa ordered the building a new record office in 1846.[2] It was completed by architect Gaspare T. Fossati in 1848. The office of "Surveillance of Treasury of Documents" was formed and Muhsin Efendi was appointed as its manager.

With the establishment of the Republic, the Hazine-i Evrak was transformed into Başvekalet Arşiv Umum Müdürlüğü (The General Directorate of the Prime Ministry) and eventually the Başbakanlık Arşiv Genel Müdürlüğü. During this period, the records of various nineteenth-century Ottoman offices and administrative authorities were added to the collections.

Concurrent with these changes and additions, Turkish scholars took the first steps to classify and catalog the various collections beginning in the 1910s. These early efforts produced a number of classified collections (tasnif) which are still cited according to the name of the scholar who created the catalog. Today the work of cataloging the vast collection continues.[1]

After more than a century in the center of the old city, the Ottoman archives were relocated in 2013 to the Kağıthane district of Istanbul.

The archives and the Armenian genocide

The Ottoman Archives not only contain information about the Ottoman dynasty and the Ottoman state, but also about each nation that holds part of these resources. Though touted as being open to all researchers, scholars have complained about being prevented access to view documents due to the nature of their research topic.[3][4][5] However, many Armenian genocide researchers including the British-Armenian Ara Sarafian and Taner Akcam (known for his research on and acceptance of the Armenian genocide) have used the Ottoman archives in Istanbul extensively when citing research for their books, though they have made claims that they were obstructed before gaining access.[6][7]

The European Parliament stressed in a resolution voted on 15 April 2015, that Turkey should use the commemoration of the centenary of the Armenian genocide as an important opportunity to recognize the Armenian genocide and open its archives.[8]

The WikiLeaks cable 04ISTANBUL1074 classified and signed by David Arnett on July 4, 2004[9] at the Consulate General of the US in Istanbul states, that Turkey has eliminated incriminating documents concerning the Armenian genocide from the archives:

According to Sabancı University Professor Halil Berktay, there were two serious efforts to purge the archives of any incriminating documents on the Armenian question. The first took place in 1918, presumably before the Allied forces occupied Istanbul. Berktay and others point to testimony in the 1919 Turkish Military Tribunals indicating that important documents had been "stolen" from the archives. Berktay believes a second purge was executed in conjunction with Ozal's efforts to open the archives by a group of retired diplomats and generals led by former Ambassador Muharrem Nuri Birgi.[10]

Gallery

Plans for Abdul Hamid Bridge, Istanbul

Plans for Abdul Hamid Bridge, Istanbul Fatih's promise to protect Christians

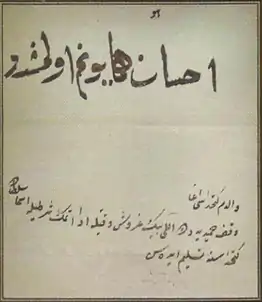

Fatih's promise to protect Christians Handwriting samples of Sultans Mustafa IV (top) and Selim III (bottom)

Handwriting samples of Sultans Mustafa IV (top) and Selim III (bottom)

References

- Christopher Markiewicz and Nir Shafir, “The Ottoman State Archives”, Hazine, 10 October 2013

- Gábor Ágoston, Bruce Masters, Prime Minister's Ottoman Archives, Encyclopedia of the Ottoman Empire, Facts On File, Inc. 2009

- Sarafian, Ara. "The Ottoman Archives Debate and the Armenian Genocide," Armenian Forum 2 (Spring 1999): pp. 35-44.

- Gingeras, Ryan (2009). Sorrowful Shores: Violence, Ethnicity, and the End of the Ottoman Empire, 1912-1923. New York: Oxford University Press. p. vii.

- Theriault, Henry C. (2003). "Denial and Free Speech: The Case of the Armenian Genocide," in Looking Backward, Moving Forward: Confronting the Armenian Genocide, ed. Richard G. Hovannisian. New Brunswick, NJ: Transactions Publishers, p. 256, note 30.

- Taner Akcam, The Young Turks Crime against Humanity: The Armenian Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing in the Ottoman Empire (Human Rights and Crimes Against Humanity)

- Sarafian, Ara (Spring 1999). "The Ottoman Archives Debate and the Armenian Genocide" (PDF). Armenian Forum. 2 (1): 34–44. Retrieved 3 March 2014.

- Armenian genocide centenary: MEPs urge Turkey and Armenia to normalize relations. European Parliament. 15 April 2015. Retrieved 15 April 2015

- Viewing cable 04ISTANBUL1074, ARMENIAN "GENOCIDE" AND THE OTTOMAN ARCHIVES. WikiLeaks. Retrieved 10 April 2015

- Cheterian, Vicken (2018a). "Censorship, Indifference, Oblivion: the Armenian Genocide and Its Denial". Truth, Silence, and Violence in Emerging States. Histories of the Unspoken. Routledge. pp. 188–214. ISBN 978-1-351-14112-3.

Further reading

- Bernard Lewis (2012). "(Ottman Archives)". Notes on a Century: Reflections of a Middle East Historian. Penguin. ISBN 978-1-101-57523-9.