Primož Trubar

Primož Trubar or Primus Truber[nb 2] (ⓘ) (1508[nb 1] – 28 June 1586)[1] was a Slovene Protestant Reformer of the Lutheran tradition, mostly known as the author of the first Slovene language printed book,[2] the founder and the first superintendent of the Protestant Church of the Duchy of Carniola, and for consolidating the Slovenian language. Trubar introduced The Reformation in Slovenia, leading the Austrian Habsburgs to wage the Counter-Reformation, which a small Protestant community survived. Trubar is a key figure of Slovenian history and in many aspects a major historical personality.[1][3]

Primož Trubar | |

|---|---|

Primož Trubar, woodcut by Jacob Lederlein, 1578 | |

| Born | 8 June 1508[nb 1] |

| Died | 28 June 1586 (aged 78) |

| Occupation | Protestant Reformer |

| Movement | Lutheranism |

Life and work

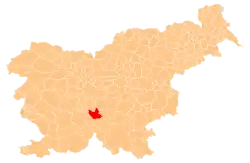

Trubar was born in the village of Rašica[4] (now in the Municipality of Velike Lašče) in the Duchy of Carniola, then under the Habsburgs. In the years 1520–1521 he attended school in Rijeka,[4] in 1522–1524 he continued his education in Salzburg. From there he went to Trieste under the tutorship of the Roman Catholic bishop Pietro Bonomo, where he got in touch with the Humanist writers, in particular Erasmus of Rotterdam.[5] In 1527 the bishop Pietro Bonomo assigned Trubar a priest position in Loka pri Zidanem Mostu.[5] In 1528 he enrolled at the University of Vienna, but did not complete his studies. In 1530 he returned to the Slovenian Lands and became a preacher in Ljubljana, where he lived up until 1565. While in Ljubljana, he lived in a house, on today's Fish Square (Ribji trg), in the oldest part of the city. Living in Ljubljana had profound impact on his work, he considered Ljubljana the capital of all Slovenes because of its central position in the heart of the Slovene lands and because its residents spoke Slovene as their first language, unlike several other towns in today's Slovenia. It is estimated that in Trubar's period around 70% of Ljubljana's 4000 inhabitants attended mass in Slovene.[6] It was the language of Ljubljana that Trubar took as a foundation of what later became standard Slovene, with small addition of his native speech, that is Lower Carniolan dialect.[6] Trubar considered Ljubljana's speech most suitable, since it sounded much more noble, than his own, simple dialect of his hometown Rašica.[7] His decision to write in Ljubljana's variety was later adopted also by other Protestant writers, who also lived in Ljubljana during Trubar's time. He gradually leaned towards Protestantism and was expelled from Ljubljana in 1547.

In 1550, while a Protestant preacher in Rothenburg, he wrote the first two books in Slovene, Catechismus and Abecedarium, which were then printed that year in Schwäbisch Hall by Peter Frentz.[8] Catechismus also contained the first Slovene musical manuscript in print.

Altogether, Trubar authored 22 books in Slovene and two books in German. He was the first to translate parts of the Bible into Slovene. After the exhortation by Pier Paolo Vergerio, he translated the Gospel of Matthew in 1555 and until 1577 in three parts published the translation of the entire New Testament.[4] In period between 1561 and 1565 Trubar was the manager and supervisor of the South Slavic Bible Institute.[9] Eschatologically minded, he also endeavored to proselytize Muslims in Turkey with his books.[10]

Trubar died in Derendingen, Holy Roman Empire (now part of the city of Tübingen, Germany), where he is also buried.[2][11]

Commemoration

On June 4, 1952, the street Šentpeterska cesta in Ljubljana was renamed Trubarjeva cesta after Trubar. It is one of the oldest roads in the city, first mentioned in 1802, and starts in Prešernov trg (Prešeren Square), named after Slovenia's national poet. The street is currently known for its high concentration of ethnic restaurants.[12]

In 1986, Slovene television produced a TV series, directed by Andrej Strojan with the screenplay written by Drago Jančar, in which Trubar was played by the Slovene actor Polde Bibič.

Trubar was commemorated on the 10 tolar banknote[13] in 1992, and on the Slovene 1 euro coin in 2007. In 2008, the Government of Slovenia proclaimed the Year of Primož Trubar and the 500th anniversary of Trubar's birth was celebrated throughout the country.[14] A commemorative €2 coin and a postage stamp were issued.[15][16][17] An exhibition dedicated to the life and work of Primož Trubar, and the achievements of the Slovene Reformation Movement was on display at the National Museum of Slovenia from 6 March to 31 December 2008.

In 2009, the Trubar Forum Association printed Trubar's Catechism and Abecedarium in modern Slovene, in a scholarly edition that includes both the Trubar-era Slovene and the modern Slovene translation with scholarly notes.[18] The "Sermon on Faith", a portion of the Catechism, is available in modern Slovene, English, German and Esperanto.

Since 2010, 8 June is commemorated in Slovenia as Primož Trubar Day.[19] Google celebrated his 505th birthday anniversary with a dedicated Google Doodle.[20]

Bibliography

Books written or published by Trubar include:

- Catechismvs. V slouenskim Iesiku sano kratko sastopno Islago. Inu ene Molytue tar Nauuki Boshy. Vseti is zhistiga suetiga pisma. Državna Založba Slovenije. 1555.

- Ta slovenski kolendar kir vselei terpi: inu ena tabla per nim, ta kasshe inu praui try inu sedemdesset leit naprei... Cankarjeva založba. 1557.

- Catechismus, mit Außlegung, in der Syruischen Sprach. Ulrich Morhardt. 1561.

- Ena duhovska peissen subper Turke inu vse sovrashnike te Cerque Boshye. Cankarjeva založba. 1567.

- Cerkovna ordninga. Trofenik.

- Kerszhanske leipe molitve sa use potreibe inu Stanuve, na usaki dan skusi ceil Tiedan, poprei v Bukovskim inu Nemshkim Jesiki, skusi Iansha Habermana pissane, Sdai pak tudi pervizh v Slovenskzhino stolmazhene, Skusi Iansha Tulszhaka. Skusi Iansha Mandelza, utim Leitu. 1579.

- Ta pervi deil tiga noviga testamenta, 1557, doi:10.3931/e-rara-79377 (Digitized Edition at E-rara).

- Katehismus. Edna malahna kniga ... : Catechismus, mit Außlegung, in der Syruischen Sprach, 1561, doi:10.3931/e-rara-79803 (Digitized Edition at E-rara).

- Ta celi catehismus : Catechismus mit des Herrn Johañis Brentzij kurtzen Außlegung in Windischer und Teutscher Sprach zůsamen getruckt, 1567, doi:10.3931/e-rara-79802 (Digitized Edition at E-rara).

- (Übersetzung:) Artikuli ili deli prave stare krstjanske vere. Confessio oder bekanntnuß des glaubens. Tübingen 1562, doi:10.3931/e-rara-79378 (Digitized edition at E-rara).

- Postila to est, kratko istlmačenǵe vsih' nedelskih' evanéliov', i poglaviteih' prazdnikov, skrozi vse leto, sada naiprvo cirulickimi slovi štampana : Kurtze auszlegung über die Sontags vnd der fürnembsten Fest Euangelia durch das gantz jar jetzt erstlich in crobatischer sprach mit Cirulischen bůchstaben getruckt. Tübingen 1562, doi:10.3931/e-rara-79379 (Digitized edition at E-rara)

Notes

- The exact date of Trubar's birth is unknown. In different encyclopedias and lexicons, it is given as 8 June 1508 or 9 June 1508, as June 1508 or simply as 1508, the last being the only reliable information.[1]

- Primož Trubar used the version Primus Truber throughout his life, except in 1550, when he used Trubar.[1]

References

- Voglar, Dušan (30 May 2008). "Primož Trubar v enciklopedijah in leksikonih I" [Primož Trubar in Encyclopedias and Lexicons I]. Locutio (in Slovenian). Vol. 11, no. 42. Maribor Literary Society. Retrieved 7 February 2011.

- "Trubar Primož". Slovenian Biographical Lexicon. Slovenian Academy of Sciences and Arts. Archived from the original on 4 November 2013. Retrieved 25 April 2013.

- "Trubar Year Dedicated to Father of Slovenian Written Word (feature)". 2 January 2008. Retrieved 7 February 2011.

- "Digitalna knjižnica Slovenije - dLib.si".

- Stanko Janež (1971). Živan Milisavac (ed.). Jugoslovenski književni leksikon [Yugoslav Literary Lexicon]. Novi Sad (SAP Vojvodina, SR Serbia: Matica srpska. pp. 543–544.

- Rigler, Jakob (1965). "Osnove Trubarjevega jezika". Jezik in Slovstvo. 10 (6–7).

- Rigler, Jakob (1968). "Začetki slovenskega knjižnega jezika. The Origins of the Slovene Literary Language, Ljubljana: Slovenska akademija znanosti in umetnosti". Razred Za Filoloske in Literarne Vede. 22.

- Ahačič, Kozma (2013). "Nova odkritja o slovenski protestantiki" [New Discoveries About the Slovene Protestant Literature] (PDF). Slavistična revija (in Slovenian and English). 61 (4): 543–555.

- Society 1990, p. 243.

- Werner Raupp (Ed.): Mission in Quellentexten. Geschichte der Deutschen Evangelischen Mission von der Reformation bis zur Weltmissionskonferenz Edinburgh 1910, Erlangen/Bad Liebenzell 1990 (ISBN 3-87214-238-0 / 3-88002-424-3), p. 49 (including source text).

- Simoniti, Primož (1980). "Auf den Spuren einer Aristophanes-Handschrift". Linguistica. 20: 21. doi:10.4312/linguistica.20.1.21-33. Retrieved 27 June 2018.

- "Trubarjeva Cesta, Ljubljana's Ethnic Food Centre". www.total-slovenia-news.com. Retrieved 8 July 2019.

- "Banka Slovenije".

- "The Year of Trubar 2008". Coordinating Committee for State Celebrations, Government of Slovenia. Protocol of the Government of the Republic of Slovenia. Government of the Republic of Slovenia Communication Office. Archived from the original on 29 October 2011. Retrieved 7 February 2011.

- "Kovanci - DBS d.d." Archived from the original on 3 October 2011. Retrieved 26 June 2011.

- "The Euro – €2 Commemorative Design 2008 – Slovenia". 22 May 2008. Retrieved 22 May 2008.

- "Prominent Slovenes". Post of Slovenia. 22 May 2008. Retrieved 7 February 2011.

- "First Slovenian Book Available in Modern Slovenian". Slovenian Press Agency. 23 October 2009.

- "Slovenia Gets Primoz Trubar Day". Slovenia Press Agency. 18 June 2010. Archived from the original on 25 March 2012. Retrieved 7 February 2011.

- "Doodles/2013". Google inc. Retrieved 8 June 2013.

- Society (1990). Slovene Studies: Journal of the Society for Slovene Studies. The Society.