Bishop of Durham

The bishop of Durham is responsible for the diocese of Durham in the province of York. The diocese is one of the oldest in England and its bishop is a member of the House of Lords. Paul Butler has been the bishop of Durham since his election was confirmed at York Minster on 20 January 2014.[1] The previous bishop was Justin Welby, now archbishop of Canterbury.

Bishop of Durham | |

|---|---|

| Bishopric | |

| Anglican | |

Coat of arms | |

| Incumbent: Paul Butler | |

| Location | |

| Ecclesiastical province | York |

| Information | |

| First holder | Aidan Aldhun (first bishop of Durham) |

| Established | 635 (at Lindisfarne) 995 (translation to Durham) |

| Diocese | Durham |

| Cathedral | Durham Cathedral (since 995) St Mary and St Cuthbert, Chester-le-Street (882–995) Lindisfarne (635–875) |

The bishop is officially styled The Right Reverend (First Name), by Divine Providence Lord Bishop of Durham, but this full title is rarely used. In signatures, the bishop's family name is replaced by Dunelm, from the Latin name for Durham (the Latinised form of Old English Dunholm). In the past, bishops of Durham varied their signatures between Dunelm and the French Duresm. Prior to 1836 the bishop had significant temporal powers over the liberty of Durham and later the county palatine of Durham. The bishop, with the bishop of Bath and Wells, escorts the sovereign at the coronation.

Durham Castle was a residence of the bishops from its construction in the 11th century until 1832, when it was given to the University of Durham to use as a college. Auckland Castle then became the bishops' main residence until July 2012, when it was sold to the Auckland Castle Trust. The bishop continues to have offices there.[2][3]

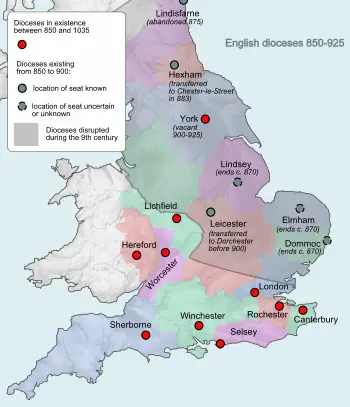

History

The bishop of Lindisfarne is an episcopal title which takes its name after the tidal island of Lindisfarne, which lies just off the northeast coast of Northumberland, England. The title was first used by the Anglo-Saxons between the 7th and 10th centuries. In the reign of Æthelstan (924–939) Wigred, thought by Simon Keynes to have been Bishop of Chester-le-Street, attested royal charters.[4] According to George Molyneaux, the church of St Cuthbert "was in all probability the greatest landholder between the Tees and the Tyne".[5] Traditionally, following the chronology of the twelfth-century writer Symeon of Durham, historians have believed that the body of St Cuthbert and centre of the diocese lay at Chester-le-Street from the ninth century until 995, but recent research has suggested that the bishops may have been based at Norham on the River Tweed until after 1013.[6] [7] The title of "bishop of Lindisfarne" is now used by the Roman Catholic Church for a titular see.

The Anglo-Saxon bishops of Lindisfarne were ordinaries of several early medieval episcopal sees (and dioceses) in Northumbria and pre-Conquest England. The first such see was founded at Lindisfarne in 635 by Saint Aidan.[8]

From the 7th century onwards, in addition to his spiritual authority, the bishops of Lindisfarne, and then Durham, also acted as the civil ruler of the region as the lord of the liberty of Durham, with local authority equal to that of the king. The bishop appointed all local officials and maintained his own court. After the Norman Conquest, this power was retained by the bishop and was eventually recognised with the designation of the region as the County Palatine of Durham. As holder of this office, the bishop was both the earl of the county and bishop of the diocese. Though the term 'prince-bishop' has become a common way of describing the role of the bishop prior to 1836, the term was unknown in Medieval England.[9]

A UNESCO site describes the role of the bishops as a "buffer state between England and Scotland":[10]

From 1075, the bishop of Durham became a prince-bishop, with the right to raise an army, mint his own coins, and levy taxes. As long as he remained loyal to the king of England, he could govern as a virtually autonomous ruler, reaping the revenue from his territory, but also remaining mindful of his role of protecting England's northern frontier.

A 1788 report adds that the bishops had the authority to appoint judges and barons and to offer pardons.[11]

Except for a brief period of suppression during the English Civil War, the bishopric retained this temporal power until it was abolished by the Durham (County Palatine) Act 1836 with the powers returned to the Crown.[12] A shadow of the former temporal power can be seen in the bishop's coat of arms, which contains a coronet as well as a mitre and crossed crozier and sword. The bishop of Durham also continued to hold a seat in the House of Lords; that has continued to this day by virtue of the ecclesiastical office.[13][14]

List of bishops

Early Medieval bishops

| Bishops of Lindisfarne | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| From | Until | Incumbent | Notes |

| 635 | 651 | Aidan | Saint Aidan. |

| 651 | 661 | Finan | Saint Finan. |

| 661 | 664 | Colmán | Saint Colmán. |

| 664 | Tuda | Saint Tuda. | |

| In 664 the diocese was merged to York by Wilfrid (who succeeded Tuda following his death), leaving one large diocese in the large northern Kingdom of Northumbria. | |||

| The diocese was reinstated in 678 by Theodore of Tarsus, Archbishop of Canterbury following Wilfrid's banishment from Northumbria by King Ecgfrith. Its new seat was initially (at least in part) at Hexham (until a new diocese was created there in 680). | |||

| 678 | 685 | Eata of Hexham | Saint Eata. |

| 685 | 687 | Cuthbert | Saint Cuthbert. |

| 688 | 698 | Eadberht | Saint Eadberht. |

| 698 | 721 | Eadfrith | Saint Eadfrith. |

| 721 | 740 | Æthelwold | Saint Æthelwold. |

| 740 | 780 | Cynewulf | |

| 780 | 803 | Higbald | |

| 803 | 821 | Egbert | |

| 821 | 830 | Heathwred | |

| 830 | 845 | Ecgred | |

| 845 | 854 | Eanbert | |

| 854 | 875 | Eardulf | |

| 883 | 889 | Eardulf | |

| 900 | c. 915 | Cutheard | |

| c. 915 | c. 925 | Tilred | |

| c. 925 | maybe 942? | Wilgred | |

| maybe 942? | unknown | Uchtred | |

| unknown, expelled after 6 months | Sexhelm | ||

| before 946 | maybe 968? | Aldred | |

| maybe 968? | maybe 968? | Ælfsige | Called "Bishop of St Cuthbert". |

| 990 | 995 | Aldhun | According to the traditional account, the see was moved to Durham. |

| In 995, the King had paid the Danegeld to the Danish and Norwegian Kings and peace was restored. According to the legend, Aldhun was on his way to reestablish the see at Lindisfarne when he received a divine vision that the body of St Cuthbert should be laid to rest in Durham. | |||

| Source(s):[15] | |||

| Bishops of Durham | |||

| From | Until | Incumbent | Notes |

| 995 | 1018 | Aldhun | |

| 1021 | 1041 | Edmund | |

| 1041 | 1042 | Eadred | |

| 1042 | 1056 | Æthelric | |

| 1056 | 1071 | Æthelwine | |

| Source(s):[16] | |||

Pre-Reformation bishops

| Bishops of Durham | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| From | Until | Incumbent | Notes |

| 1071 | 1080 | Walcher | |

| 1081 | 1096 | William de St-Calais | |

| 1099 | 1128 | Ranulf Flambard | |

| 1133 | 1140 | Geoffrey Rufus | |

| 1141 | 1143 | William Cumin | |

| 1143 | 1153 | William of St. Barbara | |

| 1153 | 1195 | Hugh de Puiset | |

| 1197 | 1208 | Philip of Poitou | |

| 1209 | 1213 | Richard Poore | Election quashed by Pope Innocent III (who was quarrelling with King John); later elected and consecrated. |

| 1214 | 1214 | John de Gray | Died before consecration. |

| 1215 | 1215 | Morgan | Election quashed. |

| 1217 | 1226 | Richard Marsh | |

| 1226 | 1227 | William Scot | Election quashed. |

| 1229 | 1237 | Richard Poore | Translated from Salisbury. |

| 1237 | 1240 | Thomas de Melsonby | Resigned before consecration. |

| 1241 | 1249 | Nicholas Farnham | |

| 1249 | 1260 | Walter of Kirkham | |

| 1260 | 1274 | Robert Stitchill | |

| 1274 | 1283 | Robert of Holy Island | |

| 1284 | 1310 | Antony Bek | Also Titular Patriarch of Jerusalem from 1306 to 1311 (the only English person ever to hold this post). |

| 1311 | 1316 | Richard Kellaw | In the ensuing vacancy, Thomas de Charlton, John Walwayn and John de Kynardesley were nominated by Edward II, Humphrey de Bohun, 4th Earl of Hereford and Thomas, 2nd Earl of Lancaster respectively, but the chapter elected Henry de Stamford OSB on 6 November 1316. That election was never confirmed, but quashed by Pope John XXII on 10 December. |

| 1317 | 1333 | Lewis de Beaumont | |

| 1333 | 1345 | Richard de Bury | |

| 1345 | 1381 | Thomas Hatfield | |

| 1382 | 1388 | John Fordham | Translated to Ely. |

| 1388 | 1406 | Walter Skirlaw | Translated from Bath & Wells. |

| 1406 | 1437 | Thomas Langley | |

| 1437 | 1457 | Robert Neville | Translated from Salisbury |

| 1457 | 1476 | Lawrence Booth | Translated to York. |

| 1476 | 1483 | William Dudley | |

| 1484 | 1494 | John Sherwood | |

| 1494 | 1501 |  Richard Foxe Richard Foxe |

Translated from Bath & Wells, later translated to Winchester. |

| 1502 | 1505 | William Senhouse | Translated from Carlisle. |

| 1507 | 1508 |  Christopher Bainbridge Christopher Bainbridge |

Translated to York. |

| 1509 | 1523 | Thomas Ruthall | |

| 1523 | 1529 |  Thomas Wolsey Thomas Wolsey |

Archbishop of York. Held Durham in commendam. |

| 1530 | 1552 |  Cuthbert Tunstall Cuthbert Tunstall |

Translated from London. |

| Source(s):[16] | |||

Post-Reformation bishops

| Bishops of Durham | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| From | Until | Incumbent | Notes |

| 1530 | 1552 |  Cuthbert Tunstall Cuthbert Tunstall |

|

| 1552 | 1554 | The diocese was abolished under Edward VI and restored after Mary I became queen.[17] | |

| 1554 | 1559 |  Cuthbert Tunstall Cuthbert Tunstall |

Deprived in 1559, when he refused to take the Oath of Supremacy after the accession of Elizabeth I. Died on 18 November that year.[18] |

| 1561 | 1576 |  James Pilkington James Pilkington |

|

| 1577 | 1587 |  Richard Barnes Richard Barnes |

Translated from Carlisle. |

| 1589 | 1595 | .jpg.webp) Matthew Hutton Matthew Hutton |

Translated to York. |

| 1595 | 1606 | _Matthew_from_NPG.jpg.webp) Tobias Matthew Tobias Matthew |

Translated to York. |

| 1606 | 1617 |  William James William James |

|

| 1617 | 1627 |  Richard Neile Richard Neile |

Translated from Lincoln, later translated to Winchester. |

| 1627 | 1628 |  George Montaigne George Montaigne |

Translated from London, later translated to York. |

| 1628 | 1632 |  John Howson John Howson |

Translated from Oxford |

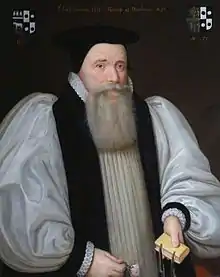

| 1632 | 1646 |  Thomas Morton Thomas Morton |

Translated from Lichfield; deprived of the see when the English episcopacy was abolished by Parliament on 9 October 1646; died 1659. |

| 1646 | 1660 | The diocese was abolished during the Commonwealth and the Protectorate.[19][20] | |

| 1660 | 1672 |  John Cosin John Cosin |

|

| 1674 | 1722 |  Nathaniel Crew Nathaniel Crew |

Translated from Oxford. |

| 1722 | 1730 |  William Talbot William Talbot |

Translated from Salisbury. |

| 1730 | 1750 |  Edward Chandler Edward Chandler |

Translated from Lichfield. |

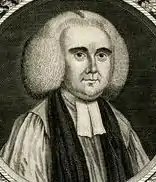

| 1750 | 1752 |  Joseph Butler Joseph Butler |

Translated from Bristol. |

| 1752 | 1771 |  Richard Trevor Richard Trevor |

Translated from St David's. |

| 1771 | 1787 |  John Egerton John Egerton |

Translated from Lichfield. |

| 1787 | 1791 |  Thomas Thurlow Thomas Thurlow |

Translated from Lincoln. |

| 1791 | 1826 |  Shute Barrington Shute Barrington |

Translated from Salisbury. |

| 1826 | 1836 |  William Van Mildert William Van Mildert |

Translated from Llandaff. |

| Source(s):[16] | |||

Late modern bishops (since 1836)

Assistant bishops

Among those who have served as assistant bishops of the diocese have been:

- 1889–1902 (ret.): Daniel Sandford, Rector of Boldon and coadjutor bishop; former Bishop of Tasmania[23]

- 1904–1906: Noel Hodges, former Bishop of Travancore and Cochin (later Assistant Bishop of Ely and of St Albans)[24]

- 1970–1975: Kenneth Skelton, Rector of Bishopwearmouth and former Bishop of Matabeleland (became Bishop of Lichfield)[25]

References

- Archbishop of York – Bishop of Durham Election Confirmed Archived 4 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine (Accessed 20 January 2014)

- "Positive Developments at Auckland Castle". Retrieved 18 August 2012.

- "Our Plans". Archived from the original on 27 September 2012. Retrieved 18 August 2012.

- Keynes, Atlas, Table XXXVII

- Molyneaux 2015, p. 30.

- Woolf 2018, pp. 232–33.

- McGuigan 2022, pp. 121–62.

- Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "Ancient Diocese and Monastery of Lindisfarne". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- Liddy, Christian D. (2008). The Bishopric of Durham in the Late Middle Ages. Woodbridge: The Boydell Press. pp. 2. ISBN 978-1-84383-377-2.

The term 'prince-bishop' did not exist in medieval England. It is a literal translation of the German compound Fürstbischof.

- "The Prince Bishops of Durham". Durham World Heritage Site. 11 July 2011. Retrieved 5 November 2019.

- Drummond Liddy, Christian (2008). The Bishopric of Durham in the Late Middle Ages. Boydell. p. 1. ISBN 978-1843833772.

- The Statutes of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. His Majesty's Statute and Law Printers. 1836. p. 130.

- "The Lord Bishop of Durham". Parliament of the United Kingdom. Retrieved 5 November 2019.

- "Lords Spiritual and Temporal". Parliament of the United Kingdom. Retrieved 5 November 2019.

- Fryde et al. 2003, pp. 214–215 and 219.

- "Historical successions: Durham (including precussor offices)". Crockford's Clerical Directory. Archived from the original on 19 June 2015. Retrieved 17 July 2012.

- "Tunstal [Tunstall], Cuthbert". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/27817. Retrieved 17 June 2023.

- . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 27 (11th ed.). 1911. p. 410.

- Plant, David (2002). "Episcopalians". BCW Project. Retrieved 25 April 2021.

- King, Peter (July 1968). "The Episcopate during the Civil Wars, 1642-1649". The English Historical Review. Oxford University Press. 83 (328): 523–537. doi:10.1093/ehr/lxxxiii.cccxxviii.523. JSTOR 564164.

- Diocese of Durham – New Bishop Announced

- "Election of Paul Butler as 74th Bishop of Durham confirmed in service". Retrieved 20 January 2014.

- "Sandford, Daniel Fox (1831–1906)". Australian Dictionary of Biography. National Centre of Biography, Australian National University.

- "Hodges, Edward Noel". Who's Who. A & C Black. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- "Skelton, Kenneth John Fraser". Who's Who. A & C Black. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

Sources

- Fryde, E. B.; Greenway, D. E.; Porter, S.; Roy, I., eds. (2003) [1986]. Handbook of British Chronology (3rd ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-56350-X.

- Keynes, Simon. "Table XXXVII: Attestations of ecclesiastics during the reign of King Æthelstan" (PDF). Kemble: The Anglo-Saxon Charters Website. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 July 2015. Retrieved 18 June 2016.

- Molyneaux, George (2015). The Formation of the English Kingdom in the Tenth Century. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-871791-1.

- Fryde, E. B.; Greenway, D. E.; Porter, S.; Roy, I., eds. (1986). Handbook of British Chronology (3rd, reprinted 2003 ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 216, 241–243. ISBN 0-521-56350-X.

- Greenway, D. E. (1971). "Bishops of Durham". Fasti Ecclesiae Anglicanae 1066–1300: Volume 2: Monastic Cathedrals (Northern and Southern Provinces). British History Online. pp. 29–32.

- Jones, B. (1963). "Bishops of Durham". Fasti Ecclesiae Anglicanae 1300–1541: Volume 6: Northern Province (York, Carlise and Durham). British History Online. pp. 107–109.

- Horn, J. M.; Smith, D. M.; Mussett, P. (2004). "Bishops of Durham". Fasti Ecclesiae Anglicanae 1541–1857: Volume 11: Carlisle, Chester, Durham, Manchester, Ripon, and Sodor and Man Dioceses. British History Online. pp. 73–77.

- McGuigan, Neil (2022), "Cuthbert's Body and the Origins of the Diocese of Durham", Anglo-Saxon England, 48: 121–162, doi:10.1017/S0263675121000053, ISSN 0263-6751, S2CID 252995619

- Woolf, Alex (2018), "The Diocese of Lindisfarne: Organization and Pastoral Care", in McGuigan, Neil; Woolf, Alex (eds.), The Battle of Carham: A Thousand Years On, Edinburgh: John Donald, pp. 231–39, ISBN 978-1910900246

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

_(cropped).jpg.webp)