Daniyal Mirza

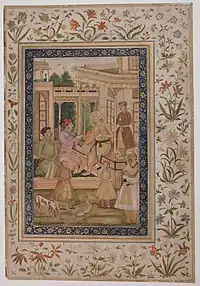

Daniyal Mirza (11 September 1572 – 19 March 1605[1]) was the shahzada of the Mughal Empire who served as the Viceroy of the Deccan.[2] He was the third son of Emperor Akbar and the half-brother of Emperor Jahangir.

| Daniyal Mirza دانیال میرزا | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shahzada of The Mughal Empire | |||||

| |||||

| Born | 11 September 1572 Ajmer, Mughal Empire | ||||

| Died | 19 March 1605 (aged 32) Burhanpur, Mughal Empire | ||||

| Burial | |||||

| Spouse |

| ||||

| Issue |

| ||||

| |||||

| House | House of Babur | ||||

| Dynasty | |||||

| Father | Akbar | ||||

| Mother |

| ||||

| Religion | Sunni Islam | ||||

Daniyal was Akbar's favourite son, as well as an able general.[3][4] Like his father, he had fine taste in poetry and was an accomplished poet himself, writing in urdu, Persian and pre-modern Hindi.[5] He was extremely fond of guns and had named one of his guns 'Yaka u Janaza'. He was very fond of horses and elephants and had once requested Akbar for gifting him his favourite horse which Akbar obliged to. He died from problems relating to alcoholism at the age of thirty-two, predeceasing Akbar by seven months.

Early life

The youngest of Akbar's three sons, Daniyal Mirza was born on 11 September 1572. He was given to Mariam-uz-Zamani, the favorite wife of Akbar, for upbringing. The birth took place in the house of Shaikh Daniyal of Ajmer, a holy man whose blessings Akbar had sought and for whom the prince was subsequently named.[6][7] The emperor, at the time embarking on an expedition to Gujarat, sent the infant Daniyal to be cared for by the Queen of Raja Bharmal of Amber. [8]

When Akbar reached Sirohi on his return from Gujarat, he ordered that Madho Singh, son of Bhagwant Das and other men be sent to fetch Daniyal from Amber and sent along Mariam-uz-Zamani for the mourning of her brother, Kunwar Bhopat, who had fallen in Battle of Sarnal.[9] Akbar met his infant son when he reached Ajmer on 13 May 1573.[10]

When he later created the Mansabdar system, Akbar awarded each of his sons exalted ranks. Daniyal, at five years old, was given the rank of 6000, with his elder brothers Salim and Murad being given greater ranks on account of their age. These provided the princes, each with an experienced guardian, huge resources to create their households, military forces, and court factions. These ranks increased as they grew older and by 1584, Daniyal's mansab had risen to 7000.[11]

The Mughal Emperor Jahangir writes in the Tuzuk-i-Jahangiri:

"Daniyal was of pleasing figure, of exceedingly agreeable manners and appearance, he was very fond of elephants and horses. It was impossible for him to hear of anyone as having a good elephant or horse and not take it from him. He was fond of Hindi songs, and would occasionally compose verses with correct idiom in the language of the people of India, which were not bad."[12]

Career

The three princes, prone to quarrelling with each other, were kept separated through assignments by their father. In such circumstances, Daniyal was dispatched to the governorship of Allahabad in 1597.[11] The prince was initially disinterested in his duties, being described as associating with undesirable characters. However, when his guardian, his father-in-law Qulij Khan Andijani, returned to court in disgust, Daniyal became apprehensive of the emperor's resulting anger. He subsequently attempted to amend his behaviour and became more involved in his administrative role.[13]

Wars in the Deccan

In response to defiance displayed by the Sultan of Ahmadnagar, Burhan Nizam Shah II, Akbar launched an invasion of the Deccan in 1593. Extensive preparations were made, and Daniyal at twenty-two years old was given supreme command of the 70,000 strong army, with Abdul Rahim Khan-I-Khana and Raja Rai Singh of Bikaner as his advisors. Prince Murad was told to be prepared to march, Shah Rukh Mirza and Shahbaz Khan were dispatched to raise troops in Malwa and even Raja Man Singh I was summoned from his distant governorship in Bengal to lead an attack from the east. However, these elaborate plans came to nothing. After having dispatched Daniyal at the head of the army from Lahore in November, Akbar was incensed to learn that his son was still loitering in Sirhind-Fategarh over a month later. The prince's command was revoked, it instead being bestowed upon Khan-I-Khana, who recommended that the invasion be delayed until a more appropriate season.[14][15]

Daniyal later was again given the opportunity to fight in the Deccan. In 1595, a succession struggle had erupted after the death of Burhan Nizam Shah. The new sultan, an infant named Bahadur Nizam Shah, was placed under the guardianship of his great-aunt, the dowager queen of Bijapur, Chand Bibi. Though an accord was eventually established between the Mughals and Ahmadnagar, skirmishes and intermittent fighting continued on both sides. After the death of his brother Murad in 1599, Daniyal was given his former command in the region.[16]

Akbar had by this point ordered a fresh attack on the Deccan. The prince first led his army to Burhanpur in January 1600, where the ruler of Khandesh, Bahadur Faruqi refused to leave the citadel and welcome him. Daniyal was furious at the insult and began summoning troops from surrounding camps to assist him in a fight against the ruler. Akbar, hearing of this, hastened to Burhanpur and ordered his son to continue his progress to the city of Ahmadnagar and to leave him to deal with the rebel himself.[17]

Hearing of the Mughal army's approach, a Nizam Shahi officer, Abhang Khan attempted to check the advance by occupying the Jaipur Kotly Ghat pass, but Daniyal took an alternate route, reaching the walls of Ahmadnagar unopposed. With the Mughals laying siege to the city, Chand Bibi was aware that her garrison would be unable to prevent an onslaught, particularly with the Mughal Emperor himself close by. However, the siege continued for several months due to the reluctance of the city officers to capitulate. Chand Bibi eventually chose to surrender, on the condition of the lives of the garrison, as well as her and the young sultan being allowed to retire safely to Junnar. Disagreeing with her, one of her advisers, Hamid Khan announced to the city that Chand Bibi was in league with the Mughals. A frenzied mob subsequently stormed her apartments and murdered her.[18] The ensuing confusion among the garrison rendered orderly defence impossible. On 18 August 1600, mines which Daniyal had planted under the city walls were detonated, resulting in the destruction of a large section, along with one of the towers. The Mughal troops assaulted and occupied the city, with all the royal children being sent to Akbar and Bahadur Nizam Shah himself being imprisoned in Gwalior.[19]

On 7 March 1601, Daniyal arrived at his father's camp and was received with honour due to his successful conquest. Khandesh, having by this point been incorporated into the empire, was renamed "Dandesh" in honour of the prince and was bestowed upon him. Afterwards, before returning to Agra, Akbar combined the provinces of Khandesh and Berar with the lands taken from Ahmadnagar to form the viceroyalty of the Deccan, which was then bestowed upon Daniyal, with Burhanpur being named his viceregal capital.[20][21]

Conflicts with Malik Ambar and Raju Deccani

The portions of the Ahmadnagar Sultanate which had remained unconquered rallied behind two nobles; the powerful regent Malik Ambar and the former minister Raju Deccani. The bitter rivalry between the two prevented the Mughals from concentrating their resources on one without giving the other an opportunity to restore his position. Daniyal therefore elected to divide the Mughal Deccan into two; Abu'l-Fazl, based in Ahmadnagar, was to lead the campaign against Raju while Khan-I-Khana, based in Berar and Telangana, headed operations against Ambar.[22]

When Ambar attacked in Telangana in 1602, Khan-I-Khana despatched his son Mirza Iraj against him. A fierce battle took place, with the Nizam Shahis being beaten back with heavy losses. Ambar, defeated and wounded, had barely avoided capture. He sued for peace with the Mughals, establishing set boundaries between their territories.[23]

Raju meanwhile refused to come out into the open, instead opting to plunder Mughal districts and harass Daniyal's army with his light cavalry. When the prince summoned Khan-I-Khana to send reinforcements, Raju was compelled to withdraw. However, his raids had demoralised the Mughal troops, forcing Daniyal to come to terms with him also. As a result, the districts contested between the two sides had their revenue split, with half going to the Mughals and half to Raju. However, this accord quickly broke down, and in spite of a subsequent defeat by the combined forces of Ambar and the Mughals, Raju would continue to conduct raids against Daniyal's Imperial forces.[24]

Death and fate of his sons

Daniyal, who suffered from severe alcoholism, died of delirium tremens on 19 March 1605, aged 32. Akbar had previously attempted to curb his addiction by restraining his access to alcohol. However, the prince's servants continued to smuggle it to him concealed in gun barrels. They were arrested afterwards by Khan-i Khana, who had them beaten and stoned to death. The emperor was deeply affected but unsurprised by his son's death, having gotten reports from the Deccan that prepared him for the news, which he received with resignation.[1][25] Akbar himself died soon after, in October of that year.[26]

Daniyal left three sons and four daughters.[1] His nephew Shah Jahan, having seized the throne following the death of Jahangir, had Daniyal's two sons, Tahmuras and Hushang, sent "out of the world" on 23 January 1628. They were executed together with Daniyal's younger nephew Shahryar, who had been Queen Nur Jahan's favourite for the throne, and with the puppet emperor Dawar Bakhsh, whom the vizier Asaf Khan had crowned as a placeholder until Shah Jahan had arrived.[27][28]

Family

His mother

The name of Daniyal's mother is not stated in Akbar's biography, the Akbarnama.[29] But Akbarnama does mention the passing of Daniyal's mother in the year 1596.[30] The Tuzk-e-Jahangiri, the chronicle of his brother Jahangir, identifies her as a royal concubine. [31]

Orientalist Henry Beveridge believed, given that Daniyal was fostered with the wife of Raja Bharmal, that the prince was related to her through his mother.[29] He was raised by the mother of Salim, Mariam-uz-Zamani.[32] Daniyal's two marriages were held at the palace of his foster mother, Mariam-uz-Zamani.

Anarkali

William Finch, an English traveler to the Mughal Court in 1611, visited what he believed to be the tomb of Daniyal's mother, whom he referred to as Anarkali. Finch stated that after Anarkali, who was Akbar's favorite concubine, was discovered to be having an affair with the then Prince Salim (Jahangir), Akbar had her sealed alive within a wall as punishment. Finch then continued that upon coming to the throne, Jahangir had the tomb erected in her memory.[33] The following Persian couplet, composed by Jahangir is inscribed on her sarcophagus:[34]

Oh, could I behold the face of my beloved once more, I would give thanks to my God until the day of resurrection.

The story was later romanticized into the modern legend commonly referred to as Selim and Anarkali.

Alternatively, the 18th-century historian Abdullah Chaghtai states that the tomb belonged to Sahib i-Jamal, a wife of Jahangir who died in 1599. He further suggests that the tomb was mistakenly associated with Anarkali (literally meaning pomegranate blossom) due to the Bagh i-Anaran (Pomegranate Garden) that once grew around it.[35]

Marriages

Daniyal's first wife was the daughter of Sultan Khwajah. The marriage took place on 10 June 1588 in the house of Daniyal's grandmother, Empress Hamida Banu Begum.[36] She was the mother of a daughter born on 26 May 1590,[37] and another daughter Sa'adat Banu Begum[1] born on 24 March 1592.[38]

His second wife was the daughter of Qulij Khan Andijani. Akbar had intended that Qulij's daughter should be married to Daniyal. On 27 October 1593 the grandees were assembled outside the city, and the marriage took place. It occurred to Qulij Khan that Akbar might visit his house. In gratitude for this great favor he arranged a feast. His request was accepted and on 4 July there was a time of enjoyment.[39] She was the mother of a son born on 27 July 1597 and died in infancy,[40] and a daughter Bulaqi Begum.[1] She died near Gwalior on 12 September 1599.[41]

His third wife was Janan Begum, the daughter of Abdurrahim Khan-i Khanan. The marriage took place around 1594. Akbar threw a great feast, and received such a quantity of presents of gold, and all sorts of precious things, that he was able to equip the army there from.[42] She was the mother of a son born on 15 February 1602 and died soon after.[43] The prince was extremely fond of her, and after his death in 1604, she led a life full of sorrow.[1]

His fourth wife was the daughter of Rai Mal, the son of Rai Maldeo, ruler of Jodhpur. The marriage took place on the eve of 12 October 1595.[44]

Daniyal's fifth wife was the daughter of Raja Dalpat Ujjainiya. She was the mother of Prince Hushang Mirza born in 1604,[45] and of Princess Mahi Begum.[1]

Another of his wives was the mother of Prince Tahmuras Mirza, Prince Baisungar Mirza born in 1604,[46] and Princess Burhani Begum.[1]

His seventh wife was Sultan Begum, the daughter of Ibrahim Adil Shah II, ruler of Bijapur.[47] He had requested that his daughter be married to Daniyal. His request was accepted, and on 19 March 1600, Mir Jamal-ud-din Hussain was sent off with the arrangements of the betrothal. When he came to Bijapur, Adil treated him with honor. After over three years he sent him away with his daughter, and Mustafa Khan as her vakil. When Abdul Rahim Khan heard of her arrival he sent his son Mirza Iraj to meet her. Mirza Iraj brought her to Ahmadnagar. Mir Jamal-ud-din hastened off from there and went to the prince in Burhanpur. Daniyal accompanied by Abdul Rahim, came to Ahmadnagar. The marriage took place on 30 June 1604.[46]

Daniyal's eldest son Tahmuras Mirza was married to Bahar Banu Begum, daughter of Jahangir, and his second son Hoshang Mirza was married to Hoshmand Banu Begum, the daughter of Khusrau Mirza.[48]

References

- Abu'l-Fazl (1973), p. 1254.

- Beni Prasad (1922). History of Jahangir. p. 496.

- Conder (1830), p. 273.

- Schimmel & Welch (1983), p. 32.

- Quddusi (2002), p. 137.

- Allan, Haig & Dodwel (1934), p. 352.

- Haig (1971), p. 102.

- Agrawal (1986), p. 28.

- Fazl, Abul. The Akbarnama. Vol. III. p. 49.

- Fazl, Abul. The Akbarnama. Vol. III. p. 54.

- Fisher (2019), p. 144.

- Jahangir, Emperor of Hindustan, 1569-1627; Rogers, Alexander; Beveridge, Henry (1909–1914). Tuzuk-i-Jahangiri. London Royal Asiatic Society. p. 36.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Sinha (1974), p. 33.

- Khan (1971), p. 61.

- Haig (1971), p. 141.

- Richards (1995), p. 54.

- Haig (1971), p. 146.

- Shyam (1966), p. 230.

- Shyam (1966), p. 231.

- Haig (1971), p. 148.

- Quddusi (2002), p. 86.

- Ali (1996), p. 67.

- Ali (1996), p. 68.

- Shyam (1966), pp. 253–54.

- Haig (1971), p. 151.

- Brown (1977), p. 37.

- Elliot & Dowson (1875), p. 438.

- Majumdar, Chaudhuri & Chaudhuri (1974), pp. 197–98.

- Abu'l-Fazl (1907), p. 543.

- Fazl, Abul. The Akbarnama. Vol. III. Translated by Beveridge, Henry. Calcutta: ASIATIC SOCIETY OF BENGAL. p. 1063.

At the end of that day the great lady of the family of chastity, the mother of Prince Sulṭān Daniel, died.

- Jahangir (1999), p. 37.

- Ahmad, Aziz (1964). Studies of Islamic culture in the Indian Environment. p. 315.

- Purchas (1905), p. 57.

- Latif (1892), p. 187.

- Hasan (2001), p. 117.

- Abu'l-Fazl (1973), p. 806.

- Abu'l-Fazl (1973), p. 875.

- Abu'l-Fazl (1973), p. 937.

- Abu'l-Fazl (1973), p. 995.

- Abu'l-Fazl (1973), p. 1090.

- Abu'l-Fazl (1973), p. 1139.

- Badayuni (1884), p. 403.

- Abu'l-Fazl (1973), p. 1200.

- Abu'l-Fazl (1973), p. 1040.

- Abu'l-Fazl (1973), p. 1238.

- Abu'l-Fazl (1973), pp. 1239–40.

- Nazim (1936), p. 10.

- Jahangir (1999), p. 436.

Bibliography

- Abu'l-Fazl (1907). The Akbarnama of Abu'l-Fazl. Vol. II. Translated by Henry Beveridge. Calcutta: The Asiatic Society.

- Abu'l-Fazl (1973) [1907]. The Akbarnama of Abu'l-Fazl. Vol. III. Translated by Henry Beveridge. Delhi: Rare Books.

- Agrawal, C. M. (1986). Akbar and his Hindu Officers: A Critical Study. ABS Publications.

- Ali, Shanti Sadiq (1996). The African Dispersal in the Deccan: From Medieval to Modern Times. New Delhi: Orient Blackswan. ISBN 978-81-250-0485-1.

- Allan, John; Haig, Wolseley; Dodwel, Henry Herbert (1934). Dodwell, Henry Herbert (ed.). The Cambridge Shorter History of India. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Badayuni, 'Abd al-Qadir (1884). Muntakhab-ut-Tawarikh. Vol. II. Translated by W. H. Lowe. Calcutta: Baptist Mission Press.

- Brown, C. (1977). Central Provinces and Berar District Gazetteers: Akola District. Vol. A. Calcutta: Baptist Mission Press.

- Conder, Josiah (1830). The Modern Traveller: A Popular Description, Geographical, Historical, and Topographical of the Various Countries of the Globe. Vol. VII. London: J. Duncan.

- Elliot, Henry Miers; Dowson, John (1875). Dowson, John (ed.). The History of India, as Told by Its Own Historians: The Muhammadan Period. Vol. VI. London: Trübner and Co.

- Fisher, Michael H. (2019) [2016]. A Short History of the Mughal Empire. London: Bloomsbury Academic. ISBN 978-1-350-12753-1.

- Haig, Wolseley (1971) [1937]. Burn, Richard (ed.). The Cambridge History Of India. Vol. IV. New Delhi: S. Chand & Co.

- Hasan, Shaikh Khurshid (2001). The Islamic Architectural Heritage of Pakistan: Funerary Memorial Architecture. Royal Book Company. ISBN 978-969-407-262-3.

- Jahangir (1829). Memoirs of the Emperor Jahangueir. Translated by David Prince. London: Oriental Translation Committee.

- Jahangir (1914). Beveridge, Henry (ed.). The Tūzuk-i-Jahāngīrī or Memoirs of Jahangir. Vol. II. Translated by Alexander Rogers. London: Royal Asiatic Society.

- Jahangir (1999). The Jahangirnama: memoirs of Jahangir, Emperor of India. Translated by Wheeler McIntosh Thackston. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-512718-8.

- Khan, Yar Muhammad (1971). The Deccan Policy of the Mughuls. Lahore: United Book Corporation.

- Latif, Syad Muhammad (1892). Lahore: Its History, Architectural Remains and Antiquities. Lahore: New Imperial Press.

- Majumdar, R. C.; Chaudhuri, J. N.; Chaudhuri, S. (1974). The Mughal Empire. Bombay: Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan.

- Moosvi, Shireen (1997). "Data on Mughal-Period Vital Statistics A Preliminary Survey of Usable Information". Proceedings of the Indian History Congress. Proceedings of the Indian History Congress, Vol. 58. 58: 342–353. JSTOR 44143926.

- Nazim, M. (1936). Bijapur Inscriptions. Memoirs of the Archæological Society of India. Delhi: Manager of Publications.

- Purchas, Samuel (1905). Hakluytus posthumus or Purchas his Pilgrimes: in twenty volumes. Vol. IV. Glasgow: James Maclehose & Sons.

- Quddusi, Mohd. Ilyas (2002). Khandesh Under the Mughals, 1601-1724 A.D.: Mainly Based on Persian Sources. Islamic Wonders Bureau. ISBN 978-81-87763-21-5.

- Richards, John F. (1995). The New Cambridge History of India: Part I, Volume 5: The Mughal Empire. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-56603-2.

- Schimmel, Annemarie; Welch, Stuart Cary (1983). Anvari's Divan: A Pocket Book for Akbar. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art. ISBN 978-0-87099-331-2.

- Sinha, Surendra Nath (1974). Subah of Allahabad Under the Great Mughals, 1580-1707. New Delhi: Jamia Millia Islamia. ISBN 9780883866030.

- Shyam, Radhey (1966). The Kingdom of Ahmadnagar. Motilal Banarsidass Publ. ISBN 978-81-208-2651-9.

- Smith, Edmund W. (1909). Akbar's tomb, Sikandarah, near Agra. Archæological Survey of India, Vol. XXXV. Allahabad: F. Luker, Supdt., Gov. Press, United Provinces.