Prise de fer

Prise de fer is a movement used in fencing in which a fencer takes the opponent's blade into a line and holds it there in preparation to attack. Translated from French, the phrase prise de fer means "taking-the-blade" or "taking-the-steel". Alternate spellings include the plural Prises de Fer or "Les Prises de Fer", and (incorrectly) Praise de Fer. There are four prise de fer actions: opposition, croisé, bind, and envelopment. However, each fencing master and fencing doctrine has a separate view of prise de fer. William Gaugler lists all four actions under Prise de Fer in his dictionary of fencing terminology,[1] while Roger Crosnier in his book Fencing with the Foil only mentions the croisé, the bind, and the envelopment as prise de fer actions.[2] Any prise de fer action requires that the blades be engaged, and it works best against an opponent who uses and maintains a straight arm. Additionally, a successful action demands surprise, precise timing, and control.[3]

| Sport | Fencing |

|---|---|

| Events | Foil, Épée |

Opposition

In the opposition, a fencer takes an opponent's blade in any line and then extends in that line, diverting the opponent's blade, until the action is complete. The opposition can be done from any line, and it is a strong attack when done with a straight thrust.[4] The amount of power needed to complete an opposition is just enough to carry the opponent's blade barely out of line, but not so much as to force it into a different line.[5]

The opposition is typically classified as an action in the French style of fencing, and it is similar to what the Italian school calls a glide. However, some doctrines teach that the opposition and the glide are separate actions, but the glide can be done using an opposition.[6] William Gaugler defines the opposition as an action completed during a thrust in which the hand is shifted against the opponent's blade in an attempt to close the line, while the glide slides along the opponent's blade onto target.[7] Louis Rondelle instructs that a glide should be kept in opposition and that it is "in reality a feint of direct thrust."[8] Julio Martinez Castello refers to the glide as a "sliding thrust" that will dominate the opponent's blade by forcing it to the side.[9]

Bind

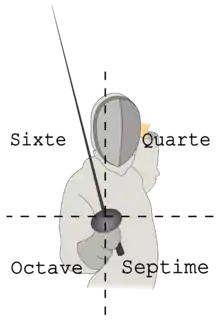

The bind takes the opponent's blade from any line diagonally to the opposing line. The action can be done from high to low line or vice versa. For example, from sixth, the opponent's blade is taken to seventh, or from eighth, the blade is taken to fourth. The bind is also known as a Transport or a Transport and Glide. As with all other prise de fer actions, there are numerous fencing doctrines. Luigi Barbasetti teaches that the bind is only done from prime, seconde, tierce, quarte, and quinte.[10] C-L. de Beaumont teaches that the bind is done by "making a half-circular movement with the blades continually in contact, carrying the opponent's blade diagonally from a high to a low line on the opposite side of the target or vice versa. The attack is then made by extending the arm and lunging, while holding the opponent's blade."[11] Julio Martinez Castello recommends that the bind be followed by a glide, but any attack is possible.[12] To complete the bind from low line, first the forearm and blade are raised with the blade slightly off line. Once the blade is sufficiently raised to high line, the arm and blade are carried across to the new line until in position.[13][14] Also see liement and flanconade below.

Croisé

The croisé carries the opponent's blade vertically from one line to the opposite line on the same side. For example, from sixth, the blade is carried to eighth. This action is sometimes referred to as a Cross, and it is well described as a semibind. However, some fencing schools believe that the croisé is only done from high line to low line.[15][16] Other fencing doctrines believe that the croisé from low line to high line is at least theoretical[17] if not truth. There are also those that believe the croisé to be a bind, as Julio Martinez Castello wrote in his book The Theory and Practice of Fencing.[18] Also see liement, flanconade, and copertino below.

Envelopment

An envelopment is conducted by starting in a line and then completing a full circular motion in order to return to that same line. This action is also known as a Circular Transfer or an Enveloppement. One school of thought is that the action is, in theory, done from any line,[19] but it works best when done from sixth because of the difficulty of holding onto the opponent's blade otherwise.[20] Jean-Jacques Gillet writes that the envolpment can be done from all lines but works particularly well in the actions that move the blade to the outside of the body.[21] Roger Crosnier writes that the size of the circle in the envelopment needs to be limited, and in order to do so, the actions must be made with the wrist, because otherwise the action would be to too slow and cumbersome and thereby easily detected and deceived.[22] Julio Martinez Castello teaches that the envelopment is essentially a combination of two binds since it completes two semicircles. In addition, he writes that the action can be followed by any attack, but preferably a glide, because that combination would continue to sustain a constant control of the opponent's blade.[23]

Miscellaneous

Liement

A liement is an action that takes the blade from high line to low line or vice versa.[24][25] Depending on the motion of the action taken, the liement can be interpreted as either a bind or a croisé. A croisé from six as well as a bind from six takes the blade from high to low line.

Flanconade

The flanconade is referenced as being a bind or a croisé. Imre Vass defines it as a "bind thrust" in which a fencer carries the opponent's blade from high line to low line on the same side but it will be the diagonal line for the opponent.[26] Depending on the motion of the action, this can be interpreted as either a bind or a croisé. William Gaugler writes that there are three flanconades: the flanconade in fourth (or external flanconade), the internal flanconade, and the flanconade in second. The flanconade in fourth is the same as a croisé from fourth whereas the internal flanconade is a transport (bind) to first from third ending with a glide to the inside low line and the flanconade in second is a transport (bind) to second from fourth ending in a glide to the outside low line.[27] Louis Rondelle explains the flanconade as starting in a high four, and then carries it downward until it terminates as a thrust under the opponent's arm.[28] This description, against a right-handed opponent, can be interpreted as a croisé.

Copertino

The copertino is another term associated with the croisé as well as the flanconade. Imre Vass differentiates the copertino and the croisé by listing them both as a "bind thrust" actions on the same side but the copertino ends on the opposite side of the opponent's blade while the croisé simply ends in the opposite line.[29] The copertino is also interpreted as a croisé.[30]

References

- Gaugler, William M, A Dictionary of Universally Used Fencing Terminology, Bangor: Laureate Press, 1997, p. 48.

- Crosnier, Roger. Fencing with the Foil, New York: A. S. Barnes and Company, 1948, p. 177-84.

- De Beaumont, C-L. Fencing: Ancient Art and Modern Sport. London: Kaye and Ward, 1978, p. 95.

- Gillet, Jean-Jacques. Foil Technique and Terminology. Livingston: United States Academy of Arms, 1977, p. 36.

- Morton, E. D. A-Z of Fencing. London: Queen Anne Press, no date, p. 129.

- Garret, Maxwell R., Emmanuil G. Kaidanov, and Gil A. Pezza. Foil, Saber, and Épeé Fencing, University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 1994, p. 50.

- Gaugler, William M. The Science of Fencing. Bangor: Laureate Press, 1997, p. 28-30.

- Rondelle, Louis. Foil and Sabre, Boston: Dana Estes and Company, 1892, p. 43

- Castello, Julio Martinez. The Theory and Practice of Fencing. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1933, p. 38.

- Barbasetti, Luigi. The Art of the Foil, New York: E. P. Dutton and Company, 1932, p. 29.

- De Beaumont, C-L. Fencing: Ancient Art and Modern Sport. London: Kaye and Ward, 1978, p. 97.

- Castello, Julio Martinez. The Theory and Practice of Fencing. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1933.

- Crosnier, Roger. Fencing with the Foil, New York: A. S. Barnes and Company, 1948, p. 180.

- De Beaumont, C-L. Fencing: Ancient Art and Modern Sport. London: Kaye and Ward, 1978, p. 97.

- Crosnier, Roger. Fencing with the Foil, New York: A. S. Barnes and Company, 1948, p. 183.

- Hett, G. V. Fencing, New York: Pitman Publishing Corporation, 1939, p. 60.

- Morton, E. D. A-Z of Fencing. London: Queen Anne Press, no date, p. 44.

- Castello, Julio Martinez. The Theory and Practice of Fencing. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1933, p. 37.

- Morton, E. D. A-Z of Fencing. London: Queen Anne Press, no date, p. 56.

- De Beaumont, C-L. Fencing: Ancient Art and Modern Sport. London: Kaye and Ward, 1978, p. 97.

- Gillet, Jean-Jacques. Foil Technique and Terminology. Livingston: United States Academy of Arms, 1977, p. 36.

- Crosnier, Roger. Fencing with the Foil, New York: A. S. Barnes and Company, 1948, p. 178.

- Castello, Julio Martinez. The Theory and Practice of Fencing. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1933, p. 37-8.

- Hett, G. V. Fencing, New York: Pitman Publishing Corporation, 1939, p. 60.

- Morton, E. D. A-Z of Fencing. London: Queen Anne Press, no date, p. 106.

- Vass, Imre. Epée Fencing: A Complete System. Staten Island: SKA Swordplay Books, 1998, p. 370.

- Gaugler, William M. A Dictionary of Universally Used Fencing Terminology. Bangor: Laureate Press, 1997, p. 34, 39.

- Rondelle, Louis. Foil and Sabre, Boston: Dana Estes and Company, 1892, p. 185-6.

- Vass, Imre. Epée Fencing: A Complete System. Staten Island: SKA Swordplay Books, 1998, p. 368.

- Morton, E. D. A-Z of Fencing. London: Queen Anne Press, no date, p. 40.

- Nadi, Aldo. On Fencing, Sunrise: Laureate Press, 1994.

- Hutton, Alfred. The Swordsman, London: H. Grevel and Company, 1891.

External links

The dictionary definition of prise de fer at Wiktionary

The dictionary definition of prise de fer at Wiktionary