Sawfish

Sawfish, also known as carpenter sharks, are a family of rays characterized by a long, narrow, flattened rostrum, or nose extension, lined with sharp transverse teeth, arranged in a way that resembles a saw. They are among the largest fish with some species reaching lengths of about 7–7.6 m (23–25 ft).[2] They are found worldwide in tropical and subtropical regions in coastal marine and brackish estuarine waters, as well as freshwater rivers and lakes. All species are endangered.[3]

| Sawfish Temporal range: | |

|---|---|

| |

| |

| Largetooth sawfish, Pristis pristis (above), Green sawfish, Pristis zijsron (below) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Chondrichthyes |

| Superorder: | Batoidea |

| Order: | Rhinopristiformes |

| Family: | Pristidae Bonaparte, 1838 |

| Genera | |

| |

They should not be confused with sawsharks (order Pristiophoriformes) or the extinct sclerorhynchoids (order Rajiformes) which have a similar appearance, or swordfish (family Xiphiidae) which have a similar name but a very different appearance.[1][4]

Sawfishes are relatively slow breeders and the females give birth to live young.[2] They feed on fish and invertebrates that are detected and captured with the use of their saw.[5] They are generally harmless to humans, but can inflict serious injuries with the saw when captured and defending themselves.[6]

Sawfish have been known and hunted for thousands of years,[7] and play an important mythological and spiritual role in many societies around the world.[8]

Once common, sawfish have experienced a drastic decline in recent decades, and the only remaining strongholds are in Northern Australia and Florida, United States.[4][9] The five species are rated as Endangered or Critically Endangered by the IUCN.[10] They are hunted for their fins (shark fin soup), use of parts as traditional medicine, their teeth and saw. They also face habitat loss.[4] Sawfish have been listed by CITES since 2007, restricting international trade in them and their parts.[11][12] They are protected in Australia, the United States and several other countries, meaning that sawfish caught by accident have to be released and violations can be punished with hefty fines.[13][14]

Taxonomy and etymology

The scientific names of the sawfish family Pristidae and its type genus Pristis are derived from the Ancient Greek: πρίστης, romanized: prístēs, lit. 'saw, sawyer'.[15][16]

Despite their appearance, sawfish are rays (superorder Batoidea). The sawfish family has traditionally been considered the sole living member of the order Pristiformes, but recent authorities have generally subsumed it into Rhinopristiformes, an order that now includes the sawfish family, as well as families containing guitarfish, wedgefish, banjo rays and the like.[17][18] Sawfish quite resemble guitarfish, except that the latter group lacks a saw, and their common ancestor likely was similar to guitarfish.[5]

Living species

The species level taxonomy in the sawfish family has historically caused considerable confusion and was often described as chaotic.[7] Only in 2013 was it firmly established that there are five living species in two genera.[4][19]

Anoxypristis contains a single living species that historically was included in Pristis, but the two genera are morphologically and genetically highly distinct.[1][20] Today Pristis contains four living, valid species divided into two species groups. Three species are in the smalltooth group, and there is only a single in the largetooth group.[4] Three poorly defined species were formerly recognized in the largetooth group, but in 2013 it was shown that P. pristis, P. microdon and P. perotteti do not differ in morphology or genetics.[19] As a consequence, recent authorities treat P. microdon and P. perotteti as junior synonyms of P. pristis.[3][21][22][23][24][25]

| Genus and species group | Image | Scientific name | Common names[10][22] (most frequently used listed first)[4] | IUCN status[10] | Distribution[10] | Main habitats[10] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anoxypristis | Anoxypristis cuspidata (Latham, 1794) |

Narrow sawfish, knifetooth sawfish, pointed sawfish |

Indo-Pacific | Marine waters, estuaries | |||

| Pristis | Smalltooths | _in_Aqua_park.png.webp) |

Pristis clavata Garman, 1906 |

Dwarf sawfish, Queensland sawfish |

Indo-Pacific | Marine waters, estuaries | |

|

Pristis pectinata Latham, 1794 |

Smalltooth sawfish | Atlantic | Marine waters, estuaries | |||

|

Pristis zijsron Bleeker, 1851 |

Green sawfish, longcomb sawfish, narrowsnout sawfish, olive sawfish |

Indo-Pacific | Marine waters, estuaries | |||

| Largetooths |  |

Pristis pristis (Linnaeus, 1758) |

Largetooth sawfish, common sawfish, wide sawfish, freshwater sawfish, river sawfish, Leichhardt's sawfish, northern sawfish |

Atlantic, Indo-Pacific, East Pacific |

Marine waters, estuaries, rivers, lakes | ||

Extinct (fossil) species

In addition to the living sawfish, there are several extinct species that only are known from fossil remains. The oldest known is the monotypic genus Peyeria whose remains date back 100 million years, from the Cenomanian age (Late Cretaceous),[1] though it may represent a rhinid rather than a sawfish.[27] Indisputable sawfish genera emerged in the Cenozoic age about 60 million years ago, relatively soon after the Cretaceous–Paleogene mass extinction. Among these are Propristis, a monotypic genus only known from fossil remains, as well as several extinct Pristis species and several extinct Anoxypristis species (both of these genera are also represented by living species).[1][28] Historically, palaeontologists have not separated Anoxypristis from Pristis.[1] In contrast, several additional extinct genera are occasionally listed, including Dalpiazia, Onchopristis, Oxypristis,[29] and Mesopristis,[28] but recent authorities generally include the first two in the family Sclerorhynchidae and the last two are synonyms of Anoxypristis.[1][30] Fossils of sawfish have been found around the world in all continents.[29]

The extinct family Sclerorhynchidae resemble sawfish. They are known only from Cretaceous fossils,[1][31] and usually reached lengths only of approximately 1 m (3.3 ft).[5][27] Some have suggested that sawfish and sclerorhynchids form a clade, the Pristiorajea,[31] while others believe the groups are not particularly close, making the proposed clade polyphyletic.[27]

Appearance and anatomy

Sawfish are dull brownish, greyish, greenish or yellowish above,[2] but the shade varies and dark individuals can be almost black.[32] The underside is pale,[32] and typically whitish.[2]

Saw

The most distinctive feature of sawfish is their saw-like rostrum with a row of whitish teeth (rostral teeth) on either side of it. The rostrum is an extension of the chondrocranium ("skull"),[27] made of cartilage and covered in skin.[33] The rostrum length is typically about one-quarter to one-third of the total length of the fish,[5] but it varies depending on species, and sometimes with age and sex.[1] The rostral teeth are not teeth in the traditional sense, but heavily modified dermal denticles.[34] The rostral teeth grow in size throughout the life of the sawfish and a tooth is not replaced if it is lost.[34][35] In Pristis sawfish the teeth are found along the entire length of the rostrum, but in adult Anoxypristis there are no teeth on the basal one-quarter of the rostrum (about one-sixth in juvenile Anoxypristis).[36][37] The number of teeth varies depending on the species and can range from 14 to 37 on each side of the rostrum.[2][38][note 1] It is common for a sawfish to have slightly different tooth counts on each side of its rostrum (difference typically does not surpass three).[39][40] In some species, females on average have fewer teeth than males.[1][39] Each tooth is peg-like in Pristis sawfish, and flattened and broadly triangular in Anoxypristis.[2] A combination of features, including fins and rostrum, are typically used to separate the species,[2][38] but it is possible to do it by the rostrum alone.[41]

Head, body and fins

_(6924477086).jpg.webp)

Sawfish have a strong shark-like body, a flat underside and a flat head. Pristis sawfish have a rough sandpaper-like skin texture because of the covering of dermal denticles, but in Anoxypristis the skin is largely smooth.[2] The mouth and nostrils are placed on the underside of the head.[2] There are about 88–128 small, blunt-edged teeth in the upper jaw of the mouth and about 84–176 in the lower jaw (not to be confused with the teeth on the saw). These are arranged in 10–12 rows on each jaw,[42] and somewhat resemble a cobblestone road.[43] They have small eyes and behind each is a spiracle, which is used to draw water past the gills.[44] The gill slits, five on each side, are placed on the underside of the body near the base of the pectoral fins.[43] The position of the gill openings separates them from the superficially similar, but generally much smaller (up to c. 1.5 m or 5 ft long) sawsharks, where the slits are placed on the side of the neck.[1][45] Unlike sawfish, sawsharks also have a pair of long barbels on the rostrum ("saw").[1][45]

Sawfish have two relatively high and distinct dorsal fins, wing-like pectoral and pelvic fins, and a tail with a distinct upper lobe and a variably sized lower lobe (lower lobe relatively large in Anoxypristis; small to absent in Pristis sawfish).[2] The position of the first dorsal fin compared to the pelvic fins varies and is a useful feature for separating some of the species.[2] There are no anal fins.[42]

Like other elasmobranches, sawfish lack a swim bladder (instead controlling their buoyancy with a large oil-rich liver), have a skeleton consisting of cartilage,[46] and the males have claspers, a pair of elongated structures used for mating and positioned on the underside at the pelvic fins.[42] The claspers are small and indistinct in young males.[38]

Their small intestines contain an internal partition shaped like a corkscrew, called a spiral valve, which increases the surface area available for food absorption.

Size

Sawfish are large to very large fish, but the maximum size of each species is generally uncertain. The smalltooth sawfish, largetooth sawfish and green sawfish are among the world's largest fish. They can certainly all reach about 6 m (20 ft) in total length and there are reports of individuals larger than 7 m (23 ft), but these are often labeled with some uncertainty.[2] Typically reported maximum total lengths of these three are from 7 to 7.6 m (23–25 ft).[2] Large individuals may weigh as much as 500–600 kg (1,102–1,323 lb),[47] or possibly even more.[48][49] Old unconfirmed and highly questionable reports of much larger individuals do exist, including one that reputedly had a length of 9.14 m (30 ft), another that had a weight of 2,400 kg (5,300 lb), and a third that was 9.45 m (31 ft) long and weighed 2,591 kg (5,712 lb).[48]

The two remaining species, the dwarf sawfish and narrow sawfish, are considerably smaller, but are still large fish with a maximum total length of at least 3.2 m (10.5 ft) and 3.5 m (11.5 ft) respectively.[2][50] In the past it was often reported that the dwarf sawfish only reaches about 1.4 m (4.6 ft), but this is now known to be incorrect.[51]

Distribution

Range

Sawfish are found worldwide in tropical and subtropical waters.[3]

Historically they ranged in the East Atlantic from Morocco to South Africa,[52] and in the West Atlantic from New York (United States)[32] to Uruguay, including the Caribbean and Gulf of Mexico.[3] There are old reports (last in the late 1950s or shortly after) from the Mediterranean and these have typically been regarded as vagrants,[3] but a review of records strongly suggests that this sea had a breeding population.[53] In the East Pacific they ranged from Mazatlán (Mexico) to northern Peru.[54] Although the Gulf of California occasionally has been included in their range, the only known Pacific Mexican records of sawfish are from south of its mouth.[54] They were widespread in the western and central Indo-Pacific, ranging from South Africa to the Red Sea and Persian Gulf, east and north to Korea and southern Japan, through Southeast Asia to Papua New Guinea and Australia.[3] Today sawfish have disappeared from much of their historical range.[3]

Habitat

_(Bimini%252C_western_Bahamas).jpg.webp)

Sawfish are primarily found in coastal marine and estuarine brackish waters, but they are euryhaline (can adapt to various salinities) and also found in freshwater.[2] The largetooth sawfish, alternatively called the freshwater sawfish, has the greatest affinity for freshwater.[55] For example, it has been reported as far as 1,340 km (830 mi) up the Amazon River and in Lake Nicaragua, and its young spend the first years of their life in freshwater.[21] In contrast, the smalltooth, green and dwarf sawfish typically avoid pure freshwater, but may occasionally move far up rivers, especially during periods when there is an increased salinity.[51][56][57] There are reports of narrow sawfish seen far upriver, but these need confirmation and may involve misidentifications of other species of sawfish.[58]

Sawfish are mostly found in relatively shallow waters, typically at depths less than 10 m (33 ft),[3] and occasionally less than 1 m (3.3 ft).[56] Young prefer very shallow places and are often found in water only 25 cm (10 in) deep.[4] Sawfish can occur offshore, but are rare deeper than 100 m (330 ft).[3] An unidentified sawfish (either a largetooth or smalltooth sawfish) was captured off Central America at a depth in excess of 175 m (575 ft).[59]

The dwarf and largetooth sawfish are strictly warm-water species that generally live in waters that are 25–32 °C (77–90 °F) and 24–32 °C (75–90 °F) respectively.[51][55] The green and smalltooth sawfish also occur in colder waters, in the latter down to 16–18 °C (61–64 °F), as illustrated by their (original) distributions that ranged further north and south of the strictly warm-water species.[55][60] Sawfish are bottom-dwellers, but in captivity it has been noted that at least the largetooth and green sawfish readily take food from the water surface.[55] Sawfish are mostly found in places with soft bottoms such as mud or sand, but may also occur over hard rocky bottoms or at coral reefs.[61] They are often found in areas with seagrass or mangrove.[3]

Sawsharks are typically found much deeper, often at depths in excess of 200 m (660 ft), and when shallower mostly in colder subtropical or temperate waters than sawfish.[1][45]

Behavior

Breeding and life cycle

Relatively little is known about the reproductive habits of the sawfish, but all species are ovoviviparous with the adult females giving birth to live young once a year or every second year.[3] In general, males appear to reach sexual maturity at a slightly younger age and smaller size than females.[3] As far as known, sexual maturity is reached at an age of 7–12 years in Pristis and 2–3 years in Anoxypristis. In the smalltooth and green sawfish this equals a total length of 3.7–4.15 m (12.1–13.6 ft), in the largetooth sawfish at 2.8–3 m (9.2–9.8 ft), in the dwarf sawfish about 2.55–2.6 m (8.4–8.5 ft), and in the narrow sawfish at 2–2.25 m (6.6–7.4 ft).[3] This means that the generation length is about 4.6 years in the narrow sawfish and 14.6–17.2 years in the remaining species.[3]

Mating involves the male inserting a clasper, organs at the pelvic fins, into the female to fertilize the eggs.[33] As known from many elasmobranchs, the mating appears to be rough, with the sawfish often sustaining lacerations from its partner's saw.[62] However, through genetic testing it has been shown that at least the smalltooth sawfish also can reproduce by parthenogenesis where no male is involved and the offspring are clones of their mother.[63][64] In Florida, United States, it appears that about 3% of the smalltooth sawfish offspring are the result of parthenogenesis.[65] It is speculated that this may be in response to being unable to find a partner, allowing the females to reproduce anyway.[64][65]

The pregnancy lasts several months.[33] There are 1–23 young in each sawfish litter, which are 60–90 cm (2–3 ft) long at birth.[3][33] In the embryos the rostrum is flexible and it only hardens shortly before birth.[33] To protect the mother the saws of the young have a soft cover, which falls off shortly after birth.[66][67] The pupping grounds are in coastal and estuarine waters. In most species the young generally stay there for the first part of their lives, occasionally moving upriver when there is an increase in salinity.[51][56][57][68] The exception is the largetooth sawfish where the young move upriver into freshwater where they stay for 3–5 years, sometimes as much as 400 km (250 mi) from the sea.[59] In at least the smalltooth sawfish the young show a degree of site fidelity, generally staying in the same fairly small area in the first part of their lives.[69] In the green and dwarf sawfish there are indications that both sexes remain in the same overall region throughout their lives with little mixing between the subpopulations. In the largetooth sawfish the males appear to move more freely between the subpopulations, while mothers return to the region where they were born to give birth to their own young.[70][71]

The length of the full lifespan of sawfish is labeled with considerable uncertainty. A green sawfish caught as a juvenile lived for 35 years in captivity,[55] and a smalltooth sawfish lived for more than 42 years in captivity.[72] In the narrow sawfish it has been estimated that the lifespan is about 9 years, and in the Pristis sawfish it has been estimated that it varies from about 30 to more than 50 years depending on the exact species.[3]

Electrolocation

The rostrum (saw), unique among jawed fish, plays a significant role in both locating and capturing prey.[73][74] The head and rostrum contain thousands of sensory organs, the ampullae of Lorenzini, that allow the sawfish to detect and monitor the movements of other organisms by measuring the electric fields they emit.[75] Electroreception is found in all cartilaginous fishes and some bony fishes. In sawfish the sensory organs are packed most densely on the upper- and underside of the rostrum, varying in position and numbers depending on the species.[75][73] Utilizing their saw as an extended sensing device, sawfish are able to examine their entire surroundings from a position close to the seafloor.[1] It appears that sawfish can detect potential prey by electroreception from a distance of about 40 cm (16 in).[5] Some waters where sawfish live are very murky, limiting the possibility of hunting by sight.[71]

Feeding

Sawfish are predators that feed on fish, crustaceans and molluscs.[2] Old stories of sawfish attacking large prey such as whales and dolphins by cutting out pieces of flesh are now considered to be wholly unsubstantiated.[1][60] Humans are far too large to be considered potential prey.[76] In captivity they are typically fed ad libitum or in set amounts that (per week) equal 1–4% of the total weight of the sawfish, but there are indications that captives grow considerably faster than their wild counterparts.[55]

Exactly how they use their saw after the prey has been located has been debated, and some scholarship on the subject has been based on speculations rather than real observations.[5][74] In 2012 it was shown that there are three primary techniques, informally called "saw in water", "saw on substrate" and "pin".[74] If a prey item such as a fish is located in the open water, the sawfish uses the first method, making a rapid swipe at the prey with its saw to incapacitate it. It is then brought to the seabed and eaten.[5][55][74] The "saw on substrate" is similar, but used on prey at the seabed.[5][74] The saw is highly streamlined and when swiped it causes very little water movement.[77] The final method involves pinning the prey against the seabed with the underside of the saw, in a manner similar to that seen in guitarfish.[5][74] The "pin" is also used to manipulate the position of the prey, allowing fish to be swallowed head-first and thus without engaging any possible fin spines.[5][74] The spines of catfish, a common prey, have been found imbedded in the rostrum of sawfish.[33] Schools of mullets have been observed trying to escape sawfish.[78] Prey fish are typically swallowed whole and not cut into small pieces with the saw,[33] although on occasion one may be split in half during capture by the slashing motion.[5] Prey choice is therefore limited by the size of the mouth.[27] A 1.3 m (4.3 ft) sawfish had a 33 cm (13 in) catfish in its stomach.[71]

It had been suggested that sawfish use their saw to dig/rake in the bottom for prey,[79] but this was not observed during a 2012 study,[74] or supported by later hydrodynamic studies.[77] Large sawfish often have rostral teeth with tips that are notably worn.[35]

Saw and self-defense

Old stories often describe sawfish as highly dangerous to humans, sinking ships and cutting people in half, but today these are considered myths and not factual.[1][60] Sawfish are actually docile and harmless to humans, except when captured, where they can inflict serious injuries when defending themselves by thrashing the saw from side-to-side.[6][16][55] The saw is also used in self-defense against predators such as sharks that may eat sawfish.[33] In captivity, they have been seen using their saws during fights over hierarchy or food.[71]

Relationship with humans

In history, culture and mythology

The largetooth sawfish was among the species formally described by Carl Linnaeus (as "Squalus pristis") in Systema Naturae in 1758,[21] but sawfish were already known thousands of years earlier.[7]

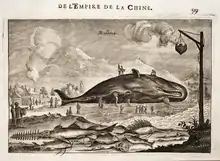

Sawfish were occasionally mentioned in antiquity, in works such as Pliny's Natural History (77–79 AD).[4] Pristis, the scientific name formalised for sawfish by Linnaeus in 1758, was also in use as a name even before his publication. For example, sawfish or "priste" were included in Libri de piscibus marinis in quibus verae piscium effigies expressae sunt by Guillaume Rondelet in 1554, and "pristi" were included in De piscibus libri V, et De cetis lib. vnus by Ulisse Aldrovandi in 1613. Outside Europe, sawfish are mentioned in old Persian texts, such as 13th century writings by Zakariya al-Qazwini.[4]

Sawfish have been found among archaeological remains in several parts of the world, including the Persian Gulf region, the Pacific coast of Panama, coastal Brazil and elsewhere.[4][80]

The cultural significance of sawfish varies significantly. The Aztecs in what is currently Mexico often included depictions of sawfish rostra (saws), notably as the striker/sword of the monster Cipactli.[81] Numerous sawfish rostra have been found buried at the Templo Mayor and two locations in coastal Veracruz had Aztec names referring to sawfish.[4] In the same general region, sawfish teeth have been found in Mayan graves.[82] The saw of sawfish is part of the dancing masks of the Huave and Zapotecs in Oaxaca, Mexico.[4][83] The Kuna people on the Caribbean coast of Panama and Colombia considers sawfish as rescuers of drowning people and protectors against dangerous sea creatures.[8] Also in Panama sawfish were recognized as containing powerful spirits that could protect humans against supernatural enemies.[8]

In the Bissagos Islands off West Africa dancing dressed as sawfish and other sea creatures is part of men's coming-of-age ceremonies.[81][84] In Gambia the saws indicate courage; the more on display at a house the more courageous the owner.[84] In Senegal the Lebu people believe the saw can protect their family, house and livestock. In the same general region they are recognized as ancestral spirits with the saw as a magic weapon. The Akan people of Ghana see sawfish as an authority symbol. There are proverbs with sawfish in the African language Duala.[85] In some other parts of coastal Africa, sawfish are considered extremely dangerous and supernatural, but their powers can be used by humans as their saw retains the powers against disease, bad luck and evil.[85] Among most African groups consumption of meat from sawfish is entirely acceptable, but in a few (in West Africa the Fula, Serer and Wolof people) it is taboo.[84] In the Niger Delta region of southern Nigeria, the saws of sawfish (known as oki in Ijaw and neighbouring languages) are often used in masquerades.[86]

In Asia, sawfish are a powerful symbol in many cultures. Asian shamans use sawfish rostrums for exorcisms and in other ceremonies to repel demons and disease.[87] They are believed to protect houses from ghosts when hung over doorways.[4] Illustrations of sawfish are often found at Buddhist temples in Thailand.[82] In the Sepik region of New Guinea locals admire sawfish, but also see them as punishers that will unleash heavy rainstorms on anyone breaking fishing taboos.[8] Among the Warnindhilyagwa, a group of Indigenous Australians, the ancestral sawfish Yukwurrirrindangwa and rays created the land. The ancestral sawfish carved out the river of Groote Eylandt with their saw.[8][88] Among European sailors sawfish were often feared as animals that could sink ships by piercing/sawing in the hull with their saw (claims now known to be entirely untrue),[60] but there are also stories of them saving people. In one case it was described how a ship almost sank during a storm in Italy in 1573. The sailors prayed and made it safely ashore where they discovered a sawfish that had "plugged" a hole in the ship with its saw. A sawfish rostrum said to be from this miraculous event is kept at the Sanctuary of Carmine Maggiore in Naples.[4]

.png.webp)

Sawfish have been used as symbols in recent history. During World War II, illustrations of sawfish were placed on navy ships, and used as symbols by both American and Nazi German submarines.[8] Sawfish served as the emblem of the German U-96 submarine, known for its portrayal in Das Boot, and was later the symbol of the 9th U-boat Flotilla. The German World War II Kampfabzeichen der Kleinkampfverbände (Battle Badge of Small Combat Units) depicted a sawfish.

In cartoons and humorous popular culture, the sawfish—particularly its rostrum ("nose")—has been employed as a sort of living tool. Examples of this can be found in Vicke Viking and Fighting Fantasy volume "Demons of the Deep".

A stylized sawfish was chosen by the Central Bank of the West African States to appear on coins and banknotes of the CFA currency. This was due to the mythological value representing fecundity and prosperity. The image takes its form from an Akan and Baoule bronze weight used for exchanges in the commercial trade of gold powder.[84]

In aquariums

Sawfish are popular in public aquariums, but require very large tanks. In a review of 10 North American and European public aquariums that kept sawfish, their tanks were all very large and ranged from about 1,500,000 to 24,200,000 L (400,000–6,390,000 US gal).[55] Individuals in public aquariums often function as "ambassadors" for sawfish and their conservation plight.[90][91] In captivity they are quite robust, appear to grow faster than their wild counterparts (perhaps due to consistent access to food) and individuals have lived for decades, but breeding them has proven difficult.[55] In 2012, four smalltooth sawfish pups were born at Atlantis Paradise Island in the Bahamas and this remains the only time a member of this family has been successfully bred in captivity[55][89] (unsuccessful breeding attempts had happened earlier at the same facility, including a miscarriage in 2003).[92] Nevertheless, it is hoped that this success may be the first step in a captive breeding program for the threatened sawfish.[4] It is speculated that seasonal variations in water temperature, salinity and photoperiod are necessary to encourage breeding.[55] Artificial insemination, as already has been done in a few captive sharks, is also being considered.[93] Tracking studies indicate that if sawfish are released to the wild after spending a period in captivity (for example, if they outgrow their exhibit), they rapidly adopt a movement pattern similar to that of fully wild sawfish.[94]

Among the five sawfish species, only the four Pristis species are known to be kept in public aquariums. The most common is the largetooth sawfish with studbooks including 16 individuals in North America in 2014, 5 individuals in Europe in 2013 and 13 individuals in Australia in 2017, followed by the green sawfish with 13 individuals in North America and 6 in Europe.[55] Both these species are also kept at public aquariums in Asia and the only captive dwarf sawfish are in Japan.[95] In 2014, studbooks included 12 smalltooth sawfish in North America,[55] and the only kept elsewhere are at a public aquarium in Colombia.[95]

Decline and conservation

Sawfish were once common, with habitat found along the coastline of 90 countries,[96] locally even abundant,[4][7] but they have declined drastically and are now among the most threatened groups of marine fish.[3]

Fishing for various uses

Sawfish and their parts have been used for numerous things. In approximate order of impact, the four most serious threats today are use in shark fin soup, as traditional medicine, rostral teeth for cockfighting spurs and the saw as a novelty item.[4] Despite being rays rather than sharks,[2] sawfish have some of most prized fins for use in shark fin soup, on level with tiger, mako, blue, porbeagle, thresher, hammerhead, blacktip, sandbar and bull shark.[97] As traditional medicine (especially Chinese medicine, but also known from Mexico, Brazil, Kenya, Eritrea, Yemen, Iran, India and Bangladesh) sawfish parts, oil or powder have been claimed to work against respiratory ailments, eye problems, rheumatism, pain, inflammation, scabies, skin ulcers, diarrhea and stomach problems, but there is no evidence supporting any of these uses.[4] The saws are used in ceremonies and as curiosities. Until relatively recently many saws were sold to visiting tourists, or through antique stores or shell shops, but they are now mostly sold online, often illegally.[4] In 2007 it was estimated that the fins and saw from a single sawfish potentially could earn a fisher more than US$5,000 in Kenya and in 2014 a single rostral tooth sold as cockfighting spurs in Peru or Ecuador had a value of up to US$220.[4] Secondary uses are the meat for consumption and the skin for leather.[4] Historically the saws were used as weapons (large saws) and combs (small saws).[88] Oil from the liver was prized for use in boat repairs and street lights,[98] and as recent as the 1920s in Florida it was regarded as the best fish oil for consumption.[4]

Sawfish fishing goes back several thousand years,[7] but until relatively recently it typically involved traditional low-intensity methods such as simple hook-and-line or spearing. In most regions the major population decline in sawfish started in the 1960s–1980s.[7][84][98] This coincided with a major growth in demand of fins for shark fin soup, the expansion of the international shark finning fishing fleet,[84] and a proliferation of modern nylon fishing nets.[98] The exception is the dwarf sawfish which was relatively widespread in the Indo-Pacific, but by the early 1900s it had already disappeared from most of its range, only surviving for certain in Australia (there is a single recent possible record from the Arabian region).[3][99] The saw has been described as sawfish's Achilles' heel, as it easily becomes entangled in fishing nets.[100] Sawfish can also be difficult or dangerous to release from nets, meaning that some fishers will kill them even before bringing them aboard the boat,[56] or cut off the saw to keep it/release the fish. Because it is their main hunting device, the long-term survival of saw-less sawfish is highly questionable.[101] In Australia where sawfish have to be released if caught, the narrow sawfish has the highest mortality rate,[68] but it is still almost 50% for dwarf sawfish caught in gill nets.[99] In an attempt of lowering this, a guide to sawfish release has been published.[102]

Habitat destruction and vulnerability to predators

Although fishing is the main cause of the drastic decline in sawfish, another serious problem is habitat destruction. Coastal and estuarine habitats, including mangrove and seagrass meadows, are often degraded by human developments and pollution, and these are important habitats for sawfish, especially their young.[4][103] In a study of juvenile sawfish in Western Australia's Fitzroy River about 60% had bite marks from bull sharks or crocodiles.[104] Changes to river flows, such as by dams or droughts, can increase the risk faced by sawfish young by bringing them into more contact with predators.[69][105][106]

21st century status

The combined range of the five sawfish species encompassed 90 countries, but today they have certainly disappeared entirely from 20 of these and possibly disappeared from several others.[3] Many more have lost at least one of their species, leaving only one or two remaining.[3] Of the five species of sawfish, three are critically endangered and two are endangered according to the International Union for Conservation of Nature's Red List of Threatened Species.[107] The sawfish is now presumed extinct in 55 nations (including China, Iraq, Haiti, Japan, Timor-Leste, El Salvador, Taiwan, Djibouti and Brunei), with 18 countries with at least one species of sawfish missing and 28 countries with at least two.[107] The United States and Australia appear to be the last strongholds of the species, where sawfish are better protected.[107] Science Advances identifies Cuba, Tanzania, Colombia, Madagascar, Panama, Brazil, Mexico and Sri Lanka as the nations where urgent action could make a big contribution to saving the species.[107]

Australia

The only remaining stronghold of the four species in the Indo-Pacific region (narrow, dwarf, largetooth and green sawfish) is in Northern Australia, but they have also experienced a decline there.[4][71] Pristis sawfish are protected in Australia and only Indigenous Australians can legally catch them.[103][108] Violations can result in a fine of up to AU$121,900.[13] The narrow sawfish does not receive the same level of protection as the Pristis sawfish.[103][109] Under CITES regulations, Australia was the only country that could export wild-caught sawfish for the aquarium trade from 2007 to 2013 (no country afterwards).[21] This strictly involved the largetooth sawfish where the Australian population remains relatively robust, and only living individuals "to appropriate and acceptable aquaria for primarily conservation purposes".[21] Numbers traded were very low (eight between 2007 and 2011),[4] and following a review Australia did not export any after 2011.[21]

Largetooth sawfish have been monitored in Fitzroy River, Western Australia, a primary stronghold for the species, since 2000. In December 2018, the largest recorded mass fish death in the river occurred when more than 40 sawfish died, mainly because of heat and a severe lack of rainfall during a poor wet season.[106] A 14-day research expedition in Far North Queensland in October 2019 did not spot a single sawfish. Expert Dr Peter Kyne of Charles Darwin University said that habitat change in the south and gillnet fishing in the north had contributed to the decline in numbers, but now that fishers had started working with the conservationists, dams and water diversions to the river flows had become a bigger problem in the north. Also, impact of successful saltwater crocodile conservation is a negative one on sawfish populations. However, there were still good populations in the Adelaide River and Daly River in the Northern Territory, and the Fitzroy River in the Kimberley.[110]

A study by Murdoch University researchers and Indigenous rangers, which captured more than 500 sawfish between 2002 and 2018, concluded that the survival of the sawfish could be at risk from dams or major water diversions on the Fitzroy River. It found that the fish are completely reliant on the Kimberley's wet season floods to complete their breeding cycle; in recent drier years, the population has suffered. There has been debate about using water from the river for agriculture and to grow fodder crops for cattle in the region.[111]

Sharks and Rays Australia (SARA) are conducting a citizen science investigation to understand the sawfish's historical habitats. Citizen can report their sawfish sighting online.[112]

Rest of the world

Except for Australia, sawfish have been extirpated or only survive in very low numbers in the Indo-Pacific region. For example, among the four species only two (narrow and largetooth sawfish) certainly survive in South Asia, and only two (narrow and green sawfish) certainly survive in Southeast Asia.[3]

The status of the two species of the Atlantic region, the smalltooth and largetooth sawfish, is comparable to the Indo-Pacific. For example, sawfish have been entirely extirpated from most of the Atlantic coast of Africa (only survives for certain in Guinea-Bissau and Sierra Leone), as well as South Africa.[3][113] The only relatively large remaining population of the largetooth sawfish in the Atlantic region is at the Amazon estuary in Brazil, but there are smaller in Central America and West Africa, and this species is also found in the Pacific and Indian Oceans.[114] The smalltooth sawfish is only found in the Atlantic region and it is possibly the most threatened of all the species, as it had the smallest original range (range c. 2,100,000 km2 or 810,000 sq mi) and has experienced the greatest contraction (disappeared from c. 81% of its original range).[4] It only survives for certain in six countries,[115] and it is possible that the only remaining viable population is in the United States.[100] In the United States the smalltooth sawfish once occurred from Texas to New York, but its numbers have declined by at least 95% and today it is essentially restricted to Florida.[116][117] However, the Florida population retains a high genetic diversity,[116] has now stabilised and appears to be slowly increasing.[82][117] A Recovery Plan for the smalltooth sawfish has been in effect since 2002.[103] It has been strictly protected in the United States since 2003 when it was added to the Endangered Species Act as the first marine fish.[118] This makes it "illegal to harm, harass, hook, or net sawfish in any way, except with a permit or in a permitted fishery".[14] The fine is up to US$10,000 for the first violation alone.[14] If accidentally caught, the sawfish has to be released as carefully as possible and a basic how-to guide has been published.[14] In 2003 an attempt of adding the largetooth sawfish to the Endangered Species Act was denied, in part because this species does not occur in the United States anymore[118] (last confirmed US record in 1961).[114] However, it was added in 2011,[119] and all the remaining sawfish species were added in 2014, restricting trade in them and their parts in the United States.[36] In 2020, a Florida fisherman used a power saw to remove a smalltooth sawfish's rostrum and then released the maimed fish; he received a fine, community service and probation.[120]

Since 2007, all sawfish species have been listed on CITES Appendix I, which prohibits international trade in them and their parts.[11][12][121] The only exception was the relatively robust Australian population of the largetooth sawfish that was listed on CITES Appendix II, which allowed trade to public aquariums only.[11] Following reviews Australia did not use this option after 2011 and in 2013 it too was moved to Appendix I.[21] In addition to Australia and the United States, sawfish are protected in the European Union, Mexico, Nicaragua, Costa Rica, Ecuador, Brazil, Indonesia, Malaysia, Bangladesh, India, Pakistan, Bahrain, Qatar, the United Arab Emirates, Guinea, Senegal and South Africa, but they are likely already functionally extirpated or entirely extirpated from several of these countries.[3][7][122][123] Illegal fishing continues and in many countries enforcement of fishing laws is lacking.[3][21] Even in Australia where relatively well-protected, people are occasionally caught illegally trying to sell sawfish parts, especially the saw.[13] The saw is distinctive, but it can be difficult to identify flesh or fins as originating from sawfish when cut up for sale at fish markets. This can be resolved with DNA testing.[124] If protected their relatively low reproduction rates make these animals especially slow to recover from overfishing.[87] An example of this is the largetooth sawfish in Lake Nicaragua where once abundant. The population rapidly crashed during the 1970s when tens of thousands were caught. It was protected by the Nicaraguan government in the early 1980s, but remains rare today.[4] Nevertheless, there are indications that at least the smalltooth sawfish population may be able to recover at a faster pace than formerly believed, if well-protected.[125] Uniquely in this family, the narrow sawfish has a relatively fast reproduction rate (generation length about 4.6 years, less than one-third the time of the other species), it has experienced the smallest contraction of its range (30%) and it is one of only two species considered Endangered rather than Critically Endangered by the IUCN.[3] The other rated as Endangered is the dwarf sawfish, but this primarily reflects that its main decline happened at least 100 years ago and IUCN ratings are based on the time period of the last three generations (estimated about 49 years in dwarf sawfish).[3][99]

There are several research projects aimed at sawfish in Australia and North America, but also a few in other continents.[126] The Florida Museum of Natural History maintains the International Sawfish Encounter Database where people worldwide are encouraged to report any sawfish encounters, whether it was living or a rostrum seen for sale in a shop/online.[4][14][82] Its data is used by biologists and conservationists for evaluating the habitat, range and abundance of sawfish around the world.[4] In an attempt of increasing the knowledge of their plight the first "Sawfish Day" was held on 17 October 2017,[83][127] and this was repeated on the same date in 2018.[128]

See also

Notes

References

- Wueringer, B.E.; L. Squire Jr.; S.P. Collin (2009). "The biology of extinct and extant sawfish (Batoidea: Sclerorhynchidae and Pristidae)". Review in Fish Biology and Fisheries. 19 (4): 445–464. doi:10.1007/s11160-009-9112-7. S2CID 3352391.

- Last; White; de Carvalho; Séret; Stehmann; Naylor (2016). Rays of the World. CSIRO. pp. 57–66. ISBN 978-0-643-10914-8.

- Dulvy; Davidson; Kyne; Simpfendorfer; Harrison; Carlson; Fordham (2014). "Ghosts of the coast: Global extinction risk and conservation of sawfishes" (PDF). Aquatic Conservation: Marine and Freshwater Ecosystems. 26 (1): 134–153. doi:10.1002/aqc.2525.

- Harrison, L.R.; N.K. Dulvy, eds. (2014). Sawfish: A Global Strategy for Conservation (PDF). IUCN Species Survival Commission's Shark Specialist Group. ISBN 978-0-9561063-3-9.

- Wueringer, B. "How sawfish use their saw". Sawfish Conservation Society. Archived from the original on 30 November 2017. Retrieved 17 November 2017.

- Froese, Rainer, and Daniel Pauly, eds. (2017). "Pristidae" in FishBase. November 2017 version.

- Moore, A.L.B. (2015). "A review of sawfishes (Pristidae) in the Arabian region: diversity, distribution, and functional extinction of large and historically abundant marine vertebrates". Aquatic Conservation. 25 (5): 656–677. doi:10.1002/aqc.2441.

- "Cultural Importance of Sawfish". Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission. Archived from the original on 1 December 2017. Retrieved 17 November 2017.

- Platt, J.R. (2 July 2013). "Last Chance for Sawfish?". Scientific American. Retrieved 17 November 2017.

- "Pristidae". IUCN Red List. International Union for Conservation of Nature. Retrieved 17 November 2017.

- Black, Richard (June 11, 2007). "Sawfish protection acquires teeth". BBC News.

- "Appendices I, II and III". CITES. 4 October 2017. Retrieved 17 November 2017.

- Slezak, M. (3 August 2016). "Queensland fisherman caught selling bills of endangered sawfish". The Guardian. Retrieved 17 November 2017.

- "Why Report Sawfish Encounters?". University of Florida. 2017-05-16. Retrieved 17 November 2017.

- πρίστης in Liddell, Henry George; Scott, Robert (1940) A Greek–English Lexicon, revised and augmented throughout by Jones, Sir Henry Stuart, with the assistance of McKenzie, Roderick. Oxford: Clarendon Press. In the Perseus Digital Library, Tufts University.

- Sullivan, T.; C. Elenberger (April 2012). "Largetooth Sawfish". University of Florida. Retrieved 17 November 2017.

- Naylor, G.J.P.; Caira, J.N.; Jensen, K.; Rosana, K.A.M.; Straube, N.; Lakner, C. (2012). "Elasmobranch Phylogeny: A Mitochondrial Estimate Based on 595 Species". In Carrier, J.C.; Musick, J.A.; Heithaus, M.R. (eds.). Biology of Sharks and Their Relatives (2 ed.). Boca Raton, Florida: CRC Press. pp. 31–56.

- Last, P.R.; Séret, B.; Naylor, G.J.P. (2016). "A new species of guitarfish, Rhinobatos borneensis sp. nov. with a redefinition of the family-level classification in the order Rhinopristiformes (Chondrichthyes: Batoidea)". Zootaxa. 4117 (4): 451–475. doi:10.11646/zootaxa.4117.4.1. PMID 27395187.

- Faria, V. V.; McDavitt, M. T.; Charvet, P.; Wiley, T. R.; Simpfendorfer, C. A.; Naylor, G. J. P. (2013). "Species delineation and global population structure of Critically Endangered sawfishes (Pristidae)". Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. 167: 136–164. doi:10.1111/j.1096-3642.2012.00872.x.

- Naylor, G.J.P.; J.N. Caira; K. Jensen; K.A.M. Rosana; W.T. White; P.R. Last (2012). "A DNA sequence-based approach to the identification of shark and ray species and its implications for global elasmobranch diversity and parasitology". Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History. 367: 1–262. doi:10.1206/754.1. hdl:2246/6183. S2CID 83264478.

- Espinoza, M.; Bonfil-Sanders, R.; Carlson, J.; Charvet, P.; Chevis, M.; Dulvy, N.K.; Everett, B.; Faria, V.; Ferretti, F.; Fordham, S.; Grant, M.I.; Haque, A.B.; Harry, A.V.; Jabado, R.W.; Jones, G.C.A.; Kelez, S.; Lear, K.O.; Morgan, D.L.; Phillips, N.M.; Wueringer, B.E. (2022). "Pristis pristis". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2022: e.T18584848A58336780. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2022-2.RLTS.T18584848A58336780.en. Retrieved 17 October 2023.

- Department of the Environment (2017). "Pristis pristis — Freshwater Sawfish, Largetooth Sawfish, River Sawfish, Leichhardt's Sawfish, Northern Sawfish". Department of the Environment and Energy. Retrieved 17 November 2017.

- Last, P.R.; De Carvalho, M.R.; Corrigan, S.; Naylor, G.J.P.; Séret, B.; Yang, L. (2016). "The Rays of the World project - an explanation of nomenclatural decisions". In Last, P.R.; Yearsley, G.R. (eds.). Rays of the World: Supplementary Information. CSIRO Special Publication. pp. 1–10. ISBN 978-1-4863-0801-9.

- Eschmeyer, W.N.; R. Fricke; R. van der Laan (17 November 2017). "Catalog of Fishes". California Academy of Sciences. Retrieved 11 November 2017.

- Pollerspöck, J.; N. Straube. "Pristis pristis". shark-references.com. Retrieved 17 November 2017.

- Cicimurri, D.J. (2009). "A Partial Rostrum of the Sawfish Pristis lathami Galeotti, 1837, from the Eocene of South Carolina". Journal of Paleontology. 81 (3): 597–601. doi:10.1666/05086.1. S2CID 130683481.

- Seitz, J.C. (2014). "A Brief Review of the Fossil Record of the Pristids and Sclerorhynchids". Fossil Sawfish. Retrieved 17 November 2017.

- "Introduction". Fossil Sawfish. Retrieved 17 November 2017.

- "Family Pristidae Bonaparte 1838 (sawfish)". Fossilworks. Retrieved 17 December 2021.

- Cappetta, H. (2012). "Chondrichthyes — Mesozoic and Cenozoic Elasmobranchii: Teeth". In Schultze, H.P. (ed.). Handbook of Paleoichthyology. Vol. 3E. Verlag F. Pfeil. ISBN 978-3-89937-148-2.

- Kriwet, J. (2004). "The systematic position of the Cretaceous sclerorhynchid sawfishes (Elasmobranchii, Pristiorajea)". In G. Arratia; A. Tintori (eds.). Systematics, Paleoenvironments and Biodiversity. Mesozoic Fishes. Vol. 3. Munich: Friedrich Pfeil. pp. 57–73. ISBN 978-3-89937-053-9.

- Kells, V.; K. Carpenter (2015). A Field Guide to Coastal Fishes from Texas to Maine. Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 82. ISBN 978-0-8018-9838-9.

- "Fisheries Fact Sheet — Sawfish" (PDF). Government of Western Australia, Fisheries Department. April 2011. Retrieved 17 November 2017.

- Welten, M.; M.M. Smith; C. Underwood; Z. Johanson (September 2015). "Evolutionary origins and development of saw-teeth on the sawfish and sawshark rostrum (Elasmobranchii; Chondrichthyes)". Royal Society Open Science. 2 (9): 150189. Bibcode:2015RSOS....250189W. doi:10.1098/rsos.150189. PMC 4593678. PMID 26473044.

- Slaughter, Bob H.; Springer, Stewart (1968). "Replacement of Rostral Teeth in Sawfishes and Sawsharks". Copeia. 1968 (3): 499–506. doi:10.2307/1442018. JSTOR 1442018.

- Marine Fisheries Service, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (12 December 2014). "Endangered and Threatened Wildlife and Plants; Final Endangered Listing of Five Species of Sawfish Under the Endangered Species Act". Federal Register. pp. 73977–74005. Retrieved 17 November 2017.

- Allen, G. (1999). Marine Fishes of Tropical Australia and South East Asia (3 ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 44–45. ISBN 978-0-7309-8363-7.

- "Sawfish Identification". Sawfish Conservation Society. Retrieved 17 November 2017.

- Wiley; Simpfendorfer; Faria; McDavitt (2008). "Range, sexual dimorphism and bilateral asymmetry of rostral tooth counts in the smalltooth sawfish Pristis pectinata Latham (Chondrichthyes: Pristidae) of the southeastern United States". Zootaxa. 1810 (2): 51–59. doi:10.2307/1442018. JSTOR 24336076.

- Schwartz, F. (2003). "Bilateral asymmetry in the rostrum of the smalltooth sawfish, Pristis pectinata (Pristiformes: Pristidae)". Journal of the North Carolina Academy of Science. 19 (2): 41–47. doi:10.2307/1442018. JSTOR 24336076.

- Whitty; Phillips; Thorburn; Simpfendorfer; Field; Peverell; Morgan (2013). "Utility of rostra in the identification of Australian sawfishes (Chondrichthyes: Pristidae)". Aquatic Conservation. 24 (6): 791–804. doi:10.1002/aqc.2398.

- "Sawfish Biology". University of Florida. 2017-05-03. Retrieved 17 November 2017.

- "Sawfish Anatomy". Sawfish Conservation Society. Retrieved 17 November 2017.

- "Sawfish Anatomy". University of Florida. 2017-05-03. Retrieved 17 November 2017.

- Compagno; Dando; Fowler (2004). Sharks of the World. Collins. pp. 131–136. ISBN 978-0-00-713610-0.

- "Sawfish". SeaPics. Retrieved 17 November 2017.

- Sullivan, T.; C. Elenberger (April 2012). "Largetooth Sawfish". University of Florida. Retrieved 11 November 2017.

- Martin, R. Aidan. "Big Fish Stories". ReefQuest Centre for Shark Research. Retrieved 17 November 2017.

- Nunes; Rincon; Piorski; Martins (2016). "Near-term embryos in a Pristis pristis (Elasmobranchii: Pristidae) from Brazil". Journal of Fish Biology. 89 (1): 1112–1120. doi:10.1111/jfb.12946. PMID 27060457.

- Curtis, Lee K.; Dennis, Andrew J.; McDonald, Keith R.; Kyne, Peter M.; Debus, Stephen J.S. (2012). Queensland's Threatened Animals. CSIRO Publishing. pp. 80–87. ISBN 978-0-643-09614-1.

- "Pristis clavata — Dwarf Sawfish, Queensland Sawfish". Department of the Environment and Energy. 2017. Retrieved 17 November 2017.

- Debelius, H. (1997). Mediterranean and Atlantic Fish Guide. IKAN Unterwasserarchiv. p. 28. ISBN 978-3-925919-54-1.

- "The Mediterranean's Missing Sawfishes". National Geographic. 22 January 2015. Retrieved 9 November 2018.

- Monte-Luna; Castro-Aguirre; Brook; de la Cruz-Agüero; Cruz-Escalona (2009). "Putative extinction of two sawfish species in Mexico and the United States". Neotropical Ichthyology. 7 (3): 508–512. doi:10.1590/S1679-62252009000300020.

- White, S.; K. Duke; Squire, L. Jr (2017). "Husbandry of sawfishes". In Mark Smith; Doug Warmolts; Dennis Thoney; Robert Hueter; Michael Murray; Juan Ezcurra (eds.). Elasmobranch Husbandry Manual II. Ohio Biological Survey. pp. 75–85. ISBN 978-0-86727-166-9.

- "Pristis zijsron — Green Sawfish, Dindagubba, Narrowsnout Sawfish". Department of the Environment and Energy. 2017. Retrieved 17 November 2017.

- Whitty, J.; N. Phillips; R. Scharfer. "Pristis pectinata (Latham, 1794)". Sawfish Conservation Society. Retrieved 17 November 2017.

- Seitz, J. (2017-05-10). "Knifetooth Sawfish". University of Florida. Retrieved 27 November 2017.

- Whitty, J.; N. Phillips. "Pristis pristis (Linnaeus, 1758)". Sawfish Conservation Society. Retrieved 17 November 2017.

- "Sawfish Myths". University of Florida. 2017-05-04. Retrieved 19 November 2017.

- Seitz, J.C.; G.R. Poulakis (2002). "Recent occurrence of the smalltooth sawfish, Pristis pectinata (Elasmobranchiomorphi: Pristidae), in Florida Bay and the Florida Keys, with comments on sawfish ecology". Florida Scientist. 65 (4): 256–266. JSTOR 24321140.

- FSUCML (14 April 2017). "Researchers Discover Critical Clue in the Mystery of Sawfish Mating". Florida State University. Retrieved 6 June 2019.

- Lee, J.J. (1 June 2015). "Rare Fish Performs "Virgin Births"—First Known in The Wild". National Geographic. Retrieved 28 February 2018.

- Fields, A.T.; K.A. Feldheim; G.R. Poulakis; D.D. Chapman (2015). "Facultative parthenogenesis in a critically endangered wild vertebrate". Current Biology. 25 (11): R446–R447. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2015.04.018. PMID 26035783.

- Zielinski, S. (5 June 2015). "'Virgin births' won't save endangered sawfish". ScienceNews. Retrieved 17 November 2017.

- Walker, S.M. (2003). Rays. Carolrhoda Books, Inc. p. 38. ISBN 978-1-57505-172-7.

- "FSUCML scores another scientific first: Dr. Dean Grubbs and colleagues document and assist pregnant sawfish give birth in the wild". Florida State University, Coastal and Marine Laboratory. 25 December 2016. Retrieved 17 November 2017.

- D'Anastasi, B.; Simpfendorfer, C. & van Herwerden, L. (2013). "Anoxypristis cuspidata". The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2013: e.T39389A18620409. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2013-1.RLTS.T39389A18620409.en.

- Poulakis, Gregg R.; Stevens, Philip W.; Timmers, Amy A.; Stafford, Christopher J.; Chapman, Demian D.; Feldheim, Kevin A.; Heupel, Michelle R.; Curtis, Caitlin (2016). "Long-term site fidelity of endangered small-tooth sawfish (Pristis pectinata) from different mothers". Fishery Bulletin. 114 (4): 461–475. doi:10.7755/fb.114.4.8.

- Feutry; Kyne; Pillans; Chen; Marthick; Morgan; Grewe (2015). "Whole mitogenome sequencing refines population structure of the Critically Endangered sawfish Pristis pristis". Marine Ecology Progress Series. 533: 237–244. Bibcode:2015MEPS..533..237F. doi:10.3354/meps11354.

- Phillips, N.; B. Wueringer (Autumn 2015). "Sawfish. Ancient predators in need of modern conservation tools". Wildlife Australia. 52 (1): 14–17.

- Jones, C. (16 November 2010). "Discovery Kingdom's sawfish off to New Orleans". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved 17 November 2017.

- Crew, Becky (2013-04-18). Zombie birds, astronaut fish, and other weird animals. Avon, Massachusetts: Adams Media. pp. 55–58. ISBN 978-1-4405-6026-2.

- Wueringer, Barbara E.; Squire, Lyle; Kajiura, Stephen M.; et al. (1 March 2012). "The function of the sawfish's saw". Current Biology. 22 (5): R150–R151. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2012.01.055. PMID 22401891.

- Wueringer, B. E.; Peverell, S. C.; Seymour, J.; et al. (1 January 2011). "Sensory Systems in Sawfishes. 1. The Ampullae of Lorenzini". Brain, Behavior and Evolution. 78 (2): 139–149. doi:10.1159/000329515. PMID 21829004. S2CID 16357946.

- "Sawfish Basics". University of Florida. 2017-05-02. Retrieved 17 November 2017.

- "Sawfish are the ultimate stealth hunters, study finds". Australian Geographic. 24 March 2017. Retrieved 28 February 2018.

- Stevens, J.D.; R.B. McAuley; C.A. Simpfendorfer; R.D. Pillans (September 2008). "Spatial distribution and habitat utilisation of sawfish (Pristis spp) in relation to fishing in northern Australia" (PDF). Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water.

- Breder, C. M. (1952). "On the utility of the saw of the sawfish". Copeia. 1952 (2): 90–91. doi:10.2307/1438539. JSTOR 1438539.

- Gonzalez, M. M. B. (2005). "Use of Pristis spp. (Elasmobranchii: Pristidae) by Hunter-Gatherers on the Coast of São Paulo, Brazil". Neotropical Ichthyology. 3 (3): 421–426. doi:10.1590/S1679-62252005000300010.

- Eilperin, J. (2012). Demon Fish: Travels Through the Hidden World of Sharks. pp. 57–66. ISBN 978-0-307-38680-9.

- Sohn, E. (March 2015). "Sawfish Recovery — Is a Mythical Fish Recovering?" (PDF). Connect: 30–35.

- "Sawfish Cultural Significance". Save Our Seas Foundation. 18 October 2017. Retrieved 17 November 2017.

- Robillard, M.; Séret, B. (2006). "Cultural importance and decline of sawfish (Pristidae) populations in West Africa". Cybium. 30 (4): 23–30.

- Helfman, G.; B. Collette (2011). Fishes: The Animal Answer Guide. Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-1-4214-0223-9.

- Blench, Roger (2006). Archaeology, language, and the African past. Altamira Press. ISBN 978-0-7591-0465-5.

- Raloff, Janet (2007). Hammered Saws, Science News vol. 172, pp. 90-92.

- McDavitt, M. T. (6–13 March 2005). "The cultural significance of sharks and rays in Aboriginal societies across Australia's top end" (PDF). Marine Education Society Australia. Retrieved 17 November 2017.

- "The endangered Smalltooth Sawfish gives birth at Atlantis, Paradise Island". Bahamas Local. 31 May 2012. Retrieved 17 November 2017.

- "Saving Sawfish". Georgia Aquarium. Retrieved 28 February 2018.

- Batesman, D. (28 November 2017). "Sawfish welcomed to new home at Cairns Aquarium". Cairns Post. Retrieved 28 February 2018.

- Henningsen; Smale; Gordon; Garner; Marin-Osorno; Kinnunen (2004). "Captive Breeding and Sexual Conflict in Elasmobranchs". In Smith, M.; D. Warmolts; D. Thoney; R. Hueter (eds.). Elasmobranch Husbandry Manual. Ohio Biological Survey. pp. 237–248. ISBN 978-0-86727-152-2.

- Campbell, F. (14 October 2017). "Endangered Sawfish takes up residence at Dubai Aquariam". The National. Retrieved 28 February 2018.

- Herrick, R. (27 October 2014). "When sawfish go wild: Released aquarium animals learn to swim with current, study finds". ABC News. Retrieved 28 February 2018.

- "Sawfish in Aquariums and the Media". Sawfish Conservation Society. Retrieved 17 November 2017.

- Briggs, Helen (11 February 2021). "'Hedge trimmer' fish facing global extinction". BBC News. Retrieved 12 February 2021.

- Vannuccini, S. 1999. Shark utilization, marketing and trade. Archived 2017-08-02 at the Wayback Machine FAO Fisheries Technical Paper. No. 389. Rome, FAO. Retrieved 17 March 2009.

- Reis-Filho; Freitas; Loiola; Leite; Soeiro; Oliveira; Sampaio; Nunes; Leduc (2016). "Traditional fisher perceptions on the regional disappearance of the largetooth sawfish Pristis pristis from the central coast of Brazil". Endanger Species Res. 2 (3): 189–200. doi:10.3354/esr00711.

- Grant, M.I.; Charles, R.; Fordham, S.; Harry, A.V.; Lear, K.O.; Morgan, D.L.; Phillips, N.M.; Simeon, B.; Wakhida, Y.; Wueringer, B.E. (2022). "Pristis clavata". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2022: e.T39390A68641215. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2022-2.RLTS.T39390A68641215.en. Retrieved 17 October 2023.

- Giglio, V.J.; O.J. Luiz; M.S. Reis; L.C. Gerhardinge (April 2016). "Memories of sawfish fisheries in a southwestern Atlantic estuary". SPC Traditional Marine Resource Management and Knowledge Information Bulletin. 36: 28–32.

- Morgan; Wringer; Allen; Ebner; Whitty; Gleiss; Beatty (2 February 2016). "What is the fate of amputee sawfish?". American Fisheries Society. Retrieved 17 November 2017.

- "A guide to releasing sawfish" (PDF). Queensland Government, Department of Primary Industries and Fisheries. 2004. Retrieved 17 November 2017.

- Smith, K.; J. Whitty. "Sawfish Conservation". Sawfish Conservation Society. Retrieved 17 November 2017.

- "Photos show crocodile eating sawfish in Australia". BBC News. 12 April 2017. Retrieved 17 November 2017.

- Morgan; Somaweera; Gleiss; Beatty; Whitty (2017). "An upstream migration fought with danger: freshwater sawfish fending off sharks and crocodiles". Ecology. 98 (5): 1465–1467. doi:10.1002/ecy.1737. PMID 28394411.

- Moodie, Claire (1 June 2019). "More than 40 dead sawfish on Gina Rinehart's cattle station fuels concern about water plan". ABC News. Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved 1 June 2019.

- "'Hedge trimmer' fish facing global extinction". BBC News. 2021-02-12. Retrieved 2021-02-12.

- "Non detriment finding for the freshwater sawfish, Pristis microdon" (PDF). Department of the Environment, Water, Heritage and the Arts. 2010. Retrieved 17 November 2017.

- "Australian endangered species: Largetooth Sawfish". The Conversation. 17 April 2014. Retrieved 27 November 2017.

- Kilvert, Nick (17 October 2019). "'I can't say it was unexpected': Sawfish research team comes home empty-handed". ABC News. Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved 22 October 2019.

- Moodie, Claire (24 December 2019). "Sawfish researchers call for protection of crucial global stronghold in the Kimberley". ABC News. Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved 24 December 2019.

- "Sharks And Rays Australia Research Organisation". Sharks And Rays Australia. Retrieved 2020-04-02.

- Everett; Cliff; Dudley; Wintner; van der Elst (2015). "Do sawfish Pristis spp. represent South Africa's first local extirpation of marine elasmobranchs in the modern era?". African Journal of Marine Science. 37 (2): 275–284. doi:10.2989/1814232X.2015.1027269. S2CID 83912626.

- Fernandez-Carvalho; Imhoff; Faria; Carlson; Burgess (2013). "Status and the potential for extinction of the largetooth sawfish Pristis pristis in the Atlantic Ocean". Aquatic Conserv: Mar. Freshw. Ecosyst. 24 (4): 478–497. doi:10.1002/aqc.2394.

- Carlson, J.; Wiley, T. & Smith, K. (2013). "Pristis pectinata". The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2013: e.T18175A43398238. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2013-1.RLTS.T18175A43398238.en.

- Chapman, Demian D.; Simpfendorfer, Colin A.; Wiley, Tonya R.; Poulakis, Gregg R.; Curtis, Caitlin; Tringali, Michael; Carlson, John K.; Feldheim, Kevin A. (2011). "Genetic Diversity Despite Population Collapse in a Critically Endangered Marine Fish: The Smalltooth Sawfish (Pristis pectinata)". Journal of Heredity. 102 (6): 643–652. doi:10.1093/jhered/esr098. ISSN 0022-1503. PMID 21926063.

- "Recovery Plan for Smalltooth Sawfish (Pristis pectinata)" (PDF). National Marine Fisheries Service. 2009. Retrieved March 18, 2009.

- Walker, C. (4 June 2003). "Sawfish Is First Sea Fish on U.S. Endangered List". National Geographic. Retrieved 17 November 2017.

- Marine Fisheries Service, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (12 July 2011). "Endangered and Threatened Wildlife and Plants; Endangered Status for the Largetooth Sawfish". Federal Register. pp. 40822–40836. Retrieved 17 November 2017.

- "Man fined $2000 for killing endangered smalltooth sawfish". 25 January 2020.

- Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (PDF). The Hague: Fourteenth meeting of the Conference of the Parties. 3–15 June 2007. pp. CoP14 Prop. 17. Retrieved 17 November 2017.

- Fordham, S.V.; Jabado, R.; Kyne, P.M.; Dulvy, N.K. (2018). "Saving Sawfish – Progress and Priorities" (PDF). IUCN Shark Specialist Group. Retrieved 9 November 2018.

- Casselman, A. Sawfish (18 April 2019). "Searching for the world's last remaining sawfish". National Geographic. Retrieved 19 June 2019.

- Palmeira; Rodrigues-Filho; Sales; Vallinoto; Schneider; Sampaio (2013). "Commercialization of a critically endangered species (largetooth sawfish, Pristis perotteti) in fish markets of northern Brazil: Authenticity by DNA analysis". Food Control. 34 (1): 249–252. doi:10.1016/j.foodcont.2013.04.017.

- Williams, T. (30 January 2018). "Recovery: Smalltooth Sawfish Flickering Back". The Nature Conservancy. Retrieved 28 February 2018.

- "Sawfish Research". Sawfish Conservation Society. Retrieved 17 November 2017.

- "Celebrating the Sawfish". Ripley's Aquarium of Canada. 12 October 2017. Retrieved 17 November 2017.

- "International Sawfish Day 2018". NOAA Fisheries. 17 October 2018. Retrieved 6 June 2019.

Further reading

- "Experts warn Australian sawfish close to dying out". SBS News. 8 January 2019.

- Kyne, Peter (17 April 2014). "Australian endangered species: Largetooth Sawfish". The Conversation.

- "Searching for the world's last remaining sawfish". Animals. 18 April 2019.

- Sawfish Australian Marine Conservation Society

- Report your sawfish sighting to Sharks and Rays Australia