Prospect Reservoir Valve House

The Prospect Reservoir Valve House is a heritage-listed waterworks located at East of Reservoir, Prospect in the City of Blacktown local government area of New South Wales, Australia. Situated on the grounds of Prospect Nature Reserve, it was designed and built by The Metropolitan Board of Water Supply and Sewerage. The property is owned by Sydney Water and Water NSW, agencies of the Government of New South Wales. It was added to the New South Wales State Heritage Register on 18 November 1999.[1]

| Prospect Reservoir Valve House | |

|---|---|

| |

| Location | East of Reservoir, Prospect, City of Fairfield, New South Wales, Australia |

| Coordinates | 33°49′33″S 150°54′35″E |

| Architect | The Metropolitan Board of Water Supply and Sewerage |

| Owner | Sydney Water; Water NSW |

| Official name | Prospect Reservoir Valve House |

| Type | State heritage (complex / group) |

| Designated | 18 November 1999 |

| Reference no. | 1371 |

| Type | Other – Utilities – Water |

| Category | Utilities – Water |

| Builders | Water Board |

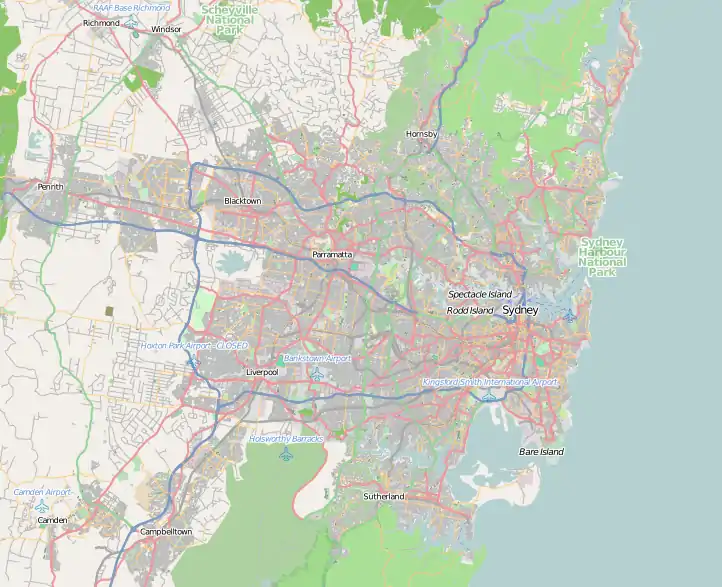

Location of Prospect Reservoir Valve House in Sydney | |

History

Indigenous history

The area of Prospect Reservoir is an area of known Aboriginal occupation, with favourable camping locations along the Eastern Creek and Prospect Creek catchments, and in elevated landscapes to the south. There is also evidence to suggest that the occupation of these lands continued after European contact, through discovery of intermingled glass and stone flakes in archaeological surveys of the place.[1]

Colonial history

The area was settled by Europeans by 1789. Prospect Hill, Sydney's largest body of igneous rock, lies centrally in the Cumberland Plain and dominates the landscape of the area.[2] Very early after first settlement, on 26 April 1788, an exploration party heading west led by Governor Phillip, climbed Prospect Hill. An account by Phillip states that the exploration party saw from Prospect Hill, "for the first time since we landed Carmathen [sic] Hills (Blue Mountains) as likewise the hills to the southward". Phillip's "Bellevue" (Prospect Hill) acquired considerable significance for the new settlers. Prospect Hill provided a point from which distances could be meaningfully calculated, and became a major reference point for other early explorers.[3] When Watkin Tench made another official journey to the west in 1789, he began his journey with reference to Prospect Hill, which commanded a view of the great chain of mountains to the west. A runaway convict, George Bruce, used Prospect Hill as a hideaway from soldiers in the mid-1790s.[1]

During the initial struggling years of European settlement in NSW, Governor Phillip began to settle time-expired convicts on the land as farmers, after the success of James Ruse at Rose Hill.[4] On 18 July 1791 Phillip placed a number of men on the eastern and southern slopes of Prospect Hill, as the soils weathered from the basalt cap were richer than the sandstone derived soils of the Cumberland Plain. The grants, mostly 30 acres, encircled Prospect Hill.[2] The settlers included William Butler, James Castle, Samuel Griffiths, John Herbert, George Lisk, Joseph Morley, John Nicols, William Parish and Edward Pugh.[4][1]

The arrival of the first settlers prompted the first organised Aboriginal resistance to the spread of settlement, with the commencement of a violent frontier conflict in which Pemulwuy and his Bidjigal clan played a central role.[5] On 1 May 1801 Governor King took drastic action, issuing a public order requiring that Aboriginal people around Parramatta, Prospect Hill and Georges River should be "driven back from the settlers" habitations by firing at them'. King's edicts appear to have encouraged a shoot-on-sight attitude whenever any Aboriginal men, women or children appeared.[5][1]

With the death of Pemulwuy, the main resistance leader, in 1802, Aboriginal resistance gradually diminished near Parramatta, although outer areas were still subject to armed hostilities. Prompted by suggestions to the Reverend Marsden by local Prospect Aboriginal groups that a conference should take place "with a view of opening the way to reconciliation", Marsden promptly organised a meeting near Prospect Hill.[5] At the meeting, held on 3 May 1805, local Aboriginal representatives discussed with Marsden ways of ending the restrictions and indiscriminate reprisals inflicted on them by soldiers and settlers in response to atrocities committed by other Aboriginal clans.[5] The meeting was significant because a group of Aboriginal women and a young free settler at Prospect named John Kennedy acted as intermediaries. The conference led to the end of the conflict for the Aboriginal clans around Parramatta and Prospect.[3] This conference at Prospect on 3 May 1805 is a landmark in Aboriginal/European relations. Macquarie's "Native Feasts" held at Parramatta from 1814 followed the precedent set in 1805. The Sydney Gazette report of the meeting is notable for the absence of the sneering tone that characterised its earlier coverage of Aboriginal matters.[5][1]

From its commencement in 1791 with the early settlement of the area, agricultural use of the land continued at Prospect Hill. Much of the land appears to have been cleared by the 1820s and pastoral use of the land was well established by then. When Governor Macquarie paid a visit to the area in 1810, he was favourably impressed by the comfortable conditions that had been created.[1][6]: 210

Nelson Lawson, third son of explorer William Lawson (1774–1850), married Honoria Mary Dickinson and before 1837 built "Greystanes House" as their future family home on the western side of Prospect Hill. Lawson had received the land from his father, who had been granted 200 hectares (500 acres) here by the illegal government that followed the overthrow of Governor Bligh in 1808.[1]

Governor Macquarie confirmed the grant, where William Lawson had built a house, which he called "Veteran Hall", because he had a commission in the NSW Veterans Company. The house was demolished in 1928 and the site is now partly covered by the waters of Prospect Reservoir. Greystanes was approached by a long drive lined with an avenue of English trees – elms (Ulmus procera), hawthorns (Crataegus sp.), holly (Ilex aquifolium), and woodbine (Clematis sp.) mingling with jacarandas (J.mimosifolia). It had a wide, semi-circular front verandah supported by 4 pillars. The foundations were of stone, the roof of slate, and the doors and architraves of heavy red cedar. It was richly furnished with articles of the best quality available and was the scene of many glittering soirees attended by the elite of the colony. Honoria Lawson died in 1845, Nelson remarried a year later, but died in 1849, and the property reverted to his father. Greystanes house was demolished in the 1940s.[1][6]: 116 [7]

By the 1870s, with the collapse of the production of cereal grains across the Cumberland Plain, the Prospect Hill area appears to have largely been devoted to livestock. The dwellings of the earliest settlers largely appear to have been removed by this stage. By the time that any mapping was undertaken in this vicinity, most of these structures had disappeared, making their locations difficult to pinpoint.[4][1]

The land was farmed from 1806–1888 when the Prospect Reservoir was built.[1]

Prospect Reservoir

_046_(40739934332).jpg.webp)

In 1867, the Governor of NSW appointed a Commission to recommend a scheme for Sydney's water supply, and by 1869 it was recommended that construction commence on the Upper Nepean Scheme. This consisted of two diversion weirs, located at Pheasant's Nest and Broughton's Pass, in the Upper Nepean River catchment, with water feeding into a series of tunnels, canals and aqueducts known as the Upper Canal System. It was intended that water be fed by gravity from the catchment into a reservoir at Prospect. This scheme was to be Sydney's fourth water supply system, following the Tank Stream, Busby's Bore and the Botany (Lachlan) Swamps.[1]

Designed and constructed by the NSW Public Works Department, Prospect Reservoir was built during the 1880s and completed in 1888. Credit for the Upper Nepean Scheme is largely given to Edward Orpen Moriarty, the Engineer in Chief of the Harbours and Rivers Branch of the Public Works Department from 1858–88.[1][8]

The Upper Nepean Scheme, completed 1888, was Sydney's fourth water supply. The scheme tapped the headwaters of the Nepean River and its tributaries, the Cataract, Cordeaux, and Avon Rivers. The system consisted of a number of diversion weirs which traversed streams and fed into a collection of tunnels, canals and aqueducts known as the Upper Canal. The canal transported the water to Prospect reservoir. From here, the Lower Canal, which moved the water to a basin at Guildford, now known as Pipehead. At this point, the water was piped to a service reservoir at Pott's Hill, thence to Crown Street and a group of minor service reservoirs located around the City. The Valve House was a key element in the Upper Nepean Water Supply Scheme, and provided Sydney with a reliable source of water from 1888.[1]

In 1895 a painting of the Prospect Reservoir including ancillary buildings was created by Arthur Streeton which was owned by the Metropolitan Water and Sewerage Board before being donated to the Art Gallery of New South Wales in 1937.[9]

Description

The valve house consists of an octagonal shaped building approximately 10 by 6 metres (33 by 20 ft) wide. Its design is based on a loose interpretation of the Victorian Free Classical style. The primary construction material is sandstone brick, with sandstone foundations and features. Although purely functional in purpose (housing the electrical valve gear), it was designed with an awareness of architectural laws and principles. The informality of the style allowed for a fair amount of flexibility in design, and the final appearance attests to a successful blending of industrial function with architectural aesthetics. It borrows elements from classical architecture, evidenced by the formal decoration of the parapet and other features, however exhibits a level of restraint in its unadornment of wall surfaces and plain window details. It is a representative example of the trend to enhance the appearance of functional civil engineering structures with restrained decoration, common to many Board-designed buildings. The Pumping station illustrates the level of enhancement which could be achieved by architects, without resorting to ostentation or gaudiness., The Valve chambers are lined with crafted brickwork, and much of the valve gear is original, although some components have been renewed. Where this has occurred, the original style and appearance have been preserved. In addition, the valve house contains what is thought to be the original weight operated "Kent " flow metres, renowned for their accuracy and reliability (this would need to be substantiated by formal investigation)., The Pumping station is a central controlling structure in the Upper Nepean Scheme, regulating the release of water from Prospect Reservoir (maximum rate 450 megalitres/day) to the Lower Canal for conveyance to Pipe Head, thence to Sydney. Since 1960, Prospect has been supplied by Warragamba, rather than the Upper Nepean Dams. An official plaque emblazens the valve house, and reads, "The Metropolitan Board of Water Supply and Sewerage, Nepean Water Supply – Completed AD 1889 – E.O. Moriarty, M.Inst.C.E. Engnieer In Chief, P.W.D."[1]

Modifications and dates

Substantially intact and in good condition. Currently regulates the supply of water from the Reservoir to Pipehead.[1]

Heritage listing

The Prospect Reservoir Valve House was a key element in the Upper Nepean Water Supply Scheme. The valve house has a high level of historic significance, as it has had a direct role in the supply and regulation of water to Sydney after the Scheme's inception in 1888. The building is representative of Board owned buildings designed in Free Classical style and is executed in such a way that allows aesthetic appreciation whilst being free of adornment or fussy decoration. The architectural expressions which imbue the building with significance at the local level include the classical parapet and lintel detail, symmetrical facade and unadorned wall surfaces. The valve house continues to be a central element of the Sydney water supply system.[1]

Prospect Reservoir Valve House was listed on the New South Wales State Heritage Register on 18 November 1999 having satisfied the following criteria.[1]

The place possesses uncommon, rare or endangered aspects of the cultural or natural history of New South Wales.

This item is assessed as historically rare statewide.[1]

The place is important in demonstrating the principal characteristics of a class of cultural or natural places/environments in New South Wales.

This item is assessed as aesthetically representative locally.[1]

References

- "Prospect Reservoir Valve House". New South Wales State Heritage Register. Department of Planning & Environment. H01371. Retrieved 2 June 2018.

Text is licensed by State of New South Wales (Department of Planning and Environment) under CC-BY 4.0 licence.

Text is licensed by State of New South Wales (Department of Planning and Environment) under CC-BY 4.0 licence. - Ashton, 2000.

- Karskens, 1991.

- Higginbotham, 2000.

- Flynn, 1999

- Pollen, F.; Healy, G. (1988). Prospect entry, in 'The Book of Sydney Suburbs'.

- amended Read, S., 2006 – the house can't have been "on the crest" of Prospect Hill as Pollon states, if its site was covered by the Reservoir

- B Cubed Sustainability P/L (2005). Prospect (Reservoir) Scour/Outlet – Heritage Impact Statement. p. 7.

- "Prospect reservoir, 1895 by Arthur Streeton". www.artgallery.nsw.gov.au. Retrieved 11 March 2022.

Bibliography

- B Cubed Sustainability P/L (2005). Prospect (Reservoir) Scour/Outlet – Heritage Impact Statement.

- Beasley, M. (1988). By the sweat of their brows – 100 years of the Sydney Water Board 1888–1988.

- Pollen, F.; Healy, G. (1988). Prospect entry, in 'The Book of Sydney Suburbs'.

- Graham Brooks and Associates Pty Ltd (1996). Sydney Water Heritage Study.

Attribution

![]() This Wikipedia article was originally based on Prospect Reservoir Valve House, entry number 01371 in the New South Wales State Heritage Register published by the State of New South Wales (Department of Planning and Environment) 2018 under CC-BY 4.0 licence, accessed on 2 June 2018.

This Wikipedia article was originally based on Prospect Reservoir Valve House, entry number 01371 in the New South Wales State Heritage Register published by the State of New South Wales (Department of Planning and Environment) 2018 under CC-BY 4.0 licence, accessed on 2 June 2018.

External links

![]() Media related to Prospect Reservoir Valve House at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Prospect Reservoir Valve House at Wikimedia Commons