Protection motivation theory

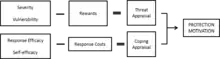

Protection motivation theory (PMT) was originally created to help understand individual human responses to fear appeals. Protection motivation theory proposes that people protect themselves based on two factors: threat appraisal and coping appraisal. Threat appraisal assesses the severity of the situation and examines how serious the situation is, while coping appraisal is how one responds to the situation. Threat appraisal consists of the perceived severity of a threatening event and the perceived probability of the occurrence, or vulnerability. Coping appraisal consists of perceived response efficacy, or an individual's expectation that carrying out the recommended action will remove the threat, and perceived self efficacy, or the belief in one's ability to execute the recommended courses of action successfully.[1][2]

PMT is one model that explains why people engage in unhealthy practices and offers suggestions for changing those behaviors. It is educational and motivational. Primary prevention: taking measures to combat the risk of developing a health problem.[3] (e.g., controlling weight to prevent high blood pressure). Secondary prevention: taking steps to prevent a condition from becoming worse.[4] (e.g., remembering to take daily medication to control blood pressure).

Another psychological model that describes self-preservation and processing of fear is terror management theory.

History

Protection motivation theory was developed by R.W. Rogers in 1975 in order to better understand fear appeals and how people cope with them.[1] However, Dr. Rogers would later expand on the theory in 1983 to a more general theory of persuasive communication. The theory was originally based on the work of Richard Lazarus, who researched how people behave and cope during stressful situations. In his book, Stress, Appraisal, and Coping, Richard Lazarus discusses the idea of the cognitive appraisal processes and how they relate to coping with stress. He states that people "differ in their sensitivity and vulnerability to certain types of events, as well as in their interpretations and reactions".[5] While Richard Lazarus came up with many of the fundamental ideas used in the protection motivation theory, Rogers was the first to apply the terminology when discussing fear appeals. In modern times, the protection motivation theory is mainly used when discussing health issues and how people react when diagnosed with health related illnesses.

Theory

Threat-appraisal process

The threat appraisal process consists of both the severity and vulnerability of the situation. It focuses on the source of the threat and factors that increase or decrease likelihood of maladaptive behaviours.[6] Severity refers to the degree of harm from the unhealthy behavior. Vulnerability is the probability that one will experience harm. Another aspect of the threat appraisal is rewards. Rewards refer to the positive aspects of starting or continuing the unhealthy behavior. To calculate the amount of threat experienced take the combination of both the severity and vulnerability, and then subtract the rewards. Threat appraisal refers to children's evaluation of the degree to which an event has significant implications for their well-being. Theoretically, threat appraisal is related to Lazaraus' concept of primary appraisal, particularly to the way in which the event threatens the child's commitments, goals, or values. Threat appraisal is differentiated from the evaluation of stressfulness or impact of the event in that is assesses what is threatened, rather than simply the degree of stress or negativity of an event. Threat appraisal is also differentiated from negative cognitive styles, because it assesses children's reported negative appraisals for specific events in their lives rather than their typical style of responding to stressful events. Theoretically, higher threat appraisals should lead to negative arousal and coping and to increased psychological symptomatology.

Coping-appraisal process

The coping appraisal consists of the response efficacy, self-efficacy, and the response costs. Response efficacy is the effectiveness of the recommended behavior in removing or preventing possible harm. Self-efficacy is the belief that one can successfully enact the recommended behavior. The response costs are the costs associated with the recommended behavior. The amount of coping ability that one experiences is the combination of response efficacy and self-efficacy, minus the response costs. The coping appraisal process focuses on the adaptive responses and one's ability to cope with and avert the threat. The coping appraisal is the sum of the appraisals of the responses efficacy and self-efficacy, minus any physical or psychological "costs" of adopting the recommended preventive response. Coping Appraisal involves the individual's assessment of the response efficacy of the recommended behavior (i.e. perceived effectiveness of sunscreen in preventing premature aging) as well as one's perceived self-efficacy in carrying out the recommended actions.[7] (i.e. confidence that one can use sunscreen consistently).

The Threat and coping appraisal variables combine in a fairly straightforward way, although the relative emphasis may vary from topic to topic and with target population.

In Stress, Appraisal, and Coping, Richard Lazarus states that, "studies of coping suggest that different styles of coping are related to specific health outcomes; control of anger, for example, has been implicated in hypertension. Three routes through which coping can affect health include the frequency, intensity, duration, and patterning of neurochemical stress reactions; using injurious substances or carrying out activities that put the person at risk; and impeding adaptive health/illness-related behavior.".[8]

Response efficacy

Response efficacy concerns beliefs that adopting a particular behavioral response will be effective in reducing the diseases' threat, and self-efficacy is the belief that one can successfully perform the coping response.[9] In line with the traditional way of measuring the consequences of behavior, response efficacy was operationalized by linking consequences to the recommended behavior as well as to whether the subject regarded the consequences as likely outcomes of the recommended behavior.[10] Among the 6 factors (vulnerability, severity, rewards, response efficacy, self-efficacy, and response costs), self-efficacy is the most correlated with protection motivation, according to meta-analysis studies.[11][12]

Applications

Measures

Each influential factor is generally measured by asking questions through a survey. For example, Boer (2005) studied on intention of condom use to prevent from getting AIDS guided by protection motivation theory. The study asked the following questions to individuals: "If I do not use condoms, I will run a high risk of getting HIV/AIDS." for vulnerability, "If I became infected with HIV or get AIDS, I would suffer from all kind of ailments." for severity, "Using condoms will protect me against becoming infected with HIV." for response efficacy, and "I am able to talk about safe sex with my boyfriend/girlfriend."[13]

Applied research areas

Protection motivation theory conventionally has been applied in the personal health contexts. A meta-analysis study on protection motivation theory categorized major six topics: cancer prevention (17%), exercise/diet/healthy lifestyle (17%), smoking (9%), AIDS prevention (9%), alcohol consumption (8%), and adherence to medical-treatment regimens (6%).[11] As the minority topics, the study presented prevention of nuclear war, wearing bicycle helmets, driving safety, child-abuse prevention, reducing caffeine consumption, seeking treatment for sexually transmitted diseases, inoculation against influenza, saving endangered species, improving dental hygiene, home radon testing, osteoporosis prevention, marijuana use, seeking emergency help via 911, pain management during and recovery after dental surgery, and safe use of pesticides.[11] All these topics were directly or indirectly related to personal physical health.

Aside from personal physical health research, the application of protection motivation theory has extended to other areas. Namely, researchers focusing on information security have applied protection motivation theory to their studies since the end of the 2000s. The general idea here has been to use threats or information security policies to encourage protection security behaviors in the workplace[14][15][16][17][18][19][20] and at home.[21] Accordingly, a more recent security application of protection motivation theory by Boss et al. (2015), returned to use of the full nomology and measurement of fear in an organizational security context with two studies. A process-variance model of protection motivation theory was strongly supported in this context, as depicted in Figure 1.[22]

See also

References

- Rogers, R. W. (1975). "A protection motivation theory of fear appeals and attitude change". Journal of Psychology. 91 (1): 93–114. doi:10.1080/00223980.1975.9915803. PMID 28136248.

- Rogers, R.W. (1983). Cognitive and physiological processes in fear appeals and attitude change: A Revised theory of protection motivation. In J. Cacioppo & R. Petty (Eds.), Social Psychophysiology. New York: Guilford Press.

- Pechmann, C; Goldberg, M; Reibling, E (2003). "What to convey in antismoking advertisements for adolescents: The Use of protection motivation theory to identify effective message themes". Journal of Marketing. 67 (2): 1–18. doi:10.1509/jmkg.67.2.1.18607.

- Maddux, J.E.; Rogers, R. W. (1983). "Protection motivation theory and self-efficacy: A revised theory of fear appeals and attitude change". Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 19 (5): 469–479. doi:10.1016/0022-1031(83)90023-9.

- Monat, A, & Lazarus, R (1991). Stress and coping: an anthology .New York: Columbia University Press .

- Plotnikoff, Ronald C.; Trinh, Linda (1 April 2010). "Protection Motivation Theory". Exercise and Sport Sciences Reviews. 38 (2): 91–98. doi:10.1097/JES.0b013e3181d49612. PMID 20335741.

- Prentice-Dunn, S, Mcmath, B, & Cramer, R (2009). Protection motivation theory and stages of change in sun protective behavior. Journal of Health Psychology , 14.

- Lazarus, R, & Folkman, S (1984). Stress, apprasisal, and coping.New York: Springer Publishing Company, Inc. .

- Van der velde, F.W.; van der Plight, J. (1991). "AIDS-related health behavior: Coping, protection, motivation, and previous behavior" (PDF). Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 14 (5): 429–451. doi:10.1007/bf00845103. PMID 1744908.

- Lwin, M, & Saw, S (2007). Protecting children from myopia: A PMT perspective for improving health marketing communications. Journal of Health Communication, 12.

- Floyd, D. L.; Prentice; Dunn, S.; Rogers, R. W. (2000). "A meta‐analysis of research on protection motivation theory". Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 30 (2): 407–429. doi:10.1111/j.1559-1816.2000.tb02323.x.

- Milne, S.; Sheeran, P.; Orbell, S. (2000). "Prediction and intervention in health‐related behavior: A meta‐analytic review of protection motivation theory". Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 30 (1): 106–143. doi:10.1111/j.1559-1816.2000.tb02308.x.

- Boer, H.; Mashamba, M. T. (2005). "Psychosocial correlates of HIV protection motivation among black adolescents in Venda, South Africa". AIDS Education and Prevention. 17 (6): 590–602. doi:10.1521/aeap.2005.17.6.590. PMID 16398579.

- Herath, T.; Rao, H. R. (2009). "Protection motivation and deterrence: a framework for security policy compliance in organisations". European Journal of Information Systems. 18 (2): 106–125. doi:10.1057/ejis.2009.6.

- Ifinedo, P (2012). "Understanding information systems security policy compliance: An integration of the theory of planned behavior and the protection motivation theory". Computers & Security. 31 (1): 83–95. doi:10.1016/j.cose.2011.10.007.

- Johnston, A. C.; Warkentin, M. (2010). "Fear appeals and information security behaviors: an empirical study". MIS Quarterly. 34 (3): 549–566. doi:10.2307/25750691. JSTOR 25750691.

- Lee, D.; Larose, R.; Rifon, N. (2008). "Keeping our network safe: a model of online protection behaviour". Behaviour & Information Technology. 27 (5): 445–454. doi:10.1080/01449290600879344.

- Clay Posey, Tom L. Roberts, and Paul Benjamin Lowry (2015). "The impact of organizational commitment on insiders’ motivation to protect organizational information assets," Journal of Management Information Systems (JMIS) (forthcoming, accepted 06-Aug-2015).

- Jenkins, Jeffrey L.; Grimes, Mark; Proudfoot, Jeff; Benjamin Lowry, Paul (2014). "Improving password cybersecurity through inexpensive and minimally invasive means: Detecting and deterring password reuse through keystroke-dynamics monitoring and just-in-time warnings". Information Technology for Development. 20 (2): 196–213. doi:10.1080/02681102.2013.814040.

- Clay Posey, Tom L. Roberts, Paul Benjamin Lowry, James Courtney, and Rebecca J. Bennett (2011). "Motivating the insider to protect organizational information assets: Evidence from protection motivation theory and rival explanations," Proceedings of the Dewald Roode Workshop in Information Systems Security 2011, IFIP WG 8.11 / 11.13, Blacksburg, VA, September 22–23, pp. 1–51.

- Nehme, Alaa; George, Joey F. (2022). "Approaching IT Security & Avoiding Threats in the Smart Home Context" (PDF). Journal of Management Information Systems. 39 (4): 1184–1214. doi:10.1080/07421222.2022.2127449.

- Boss, Scott R.; Galletta, Dennis F.; Benjamin Lowry, Paul; Moody, Gregory D.; Polak, Peter (2015). "What do users have to fear? Using fear appeals to engender threats and fear that motivate protective behaviors in users". MIS Quarterly. 39 (4): 837–864. doi:10.25300/MISQ/2015/39.4.5. SSRN 2607190.