Protector of the Indians

Protector of the Indians (Spanish: Protectoría de Los Indios) was an administrative office of the Spanish colonies that deemed themselves responsible for attending to the well-being of the native populations by providing detailed witness accounts of mistreatment in an attempt to relay their struggles and a voice speaking on their behalf in courts, reporting back to the King of Spain.[1] The establishment of the administration of the Protector of the Indians is due in part to Bartolomé de las Casas – the first Protector of the American Indians, and Fray Francisco Jimenez de Cisneros, the great Cardinal Regent of Spain.[2] Throughout this era, the King of Spain gained information regarding the treatment of native peoples through Bartolomé de las Casas and Fray Francisco Jimenez de Cisneros. Bartolomé de las Casas was one of the first Europeans to set foot into the new hemisphere. He later dedicated his life to ending the harsh treatment of Indigenous Americans.[3] The institution of the Protectors of the Indians rested on the idea that rulers should appoint officials to defend, both within and outside of the courts of justice, individuals who were less favored.[4]

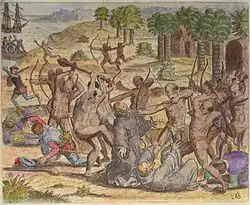

.jpg.webp)

Origins

As previously stated, the immediate origin of the Protector of the Indians is mainly due to Fray Bartolome de las Casas and Cardinal Cisneros. The first steps towards implementing protection policies for indigenous peoples are believed to have commenced in 1516.[2] Several Hieronymites friars (individuals that make up the Hieronymite monastic order in Spain[5]), including Bartolome de las Casas, were sent to the Spanish colonies to evaluate the actions and consequences that colonization was having upon the demographic decline of the native population.[3] The Indians faced other effects such as forced conversion to Christianity.[3] The report by Fray Bartolome de las Casas to Cardinal Cisneros is probably the first documented attempt of those efforts when the bishops took upon themselves the task of exercising protective actions on the native population.[6][7] Bartolome de las Casas presented this report to the Spanish Court in 1516, denouncing the harm and cruelties imposed on native peoples of the colonies.[2] After that, the kings of Spain, or the governors in their name, took it upon themselves to designate and appoint individuals, such as bishops, friars, and civilians, as protectors of the Indians.[2]

Cisneros granted the title of Protector de Indios to Bartolomé de las Casas, and he was given instructions to serve as an adviser regarding issues concerning the native population. Bartolomé de las Casas was also asked to speak on their behalf during legal proceedings, reporting back to Spain. For over fifty years, while traveling to and from the New World and the court of Spain, Bartolomé de las Casas used his books, letters, and preaching to defend native peoples and reveal the harshness of such unjust conquests. Other notable protectors included Juan de Zumárraga (appointed 1527) and Hernando de Luque (appointed 1529).

Bartolomé de las Casas

As argued by Diego von Vacano in his article Las Casas and the Birth of Race, the first theorist to lay the grounds for a racial conception in politics was Bartolomé de las Casas. Las Casas contributed to the administration of the Protector of the Indians significantly during his time in Spain. Las Casas was a participant in the Spanish conquest until his eyes were opened to the horrors of the conquest experienced by the native populations. After witnessing the harsh treatment of native people in Spanish colonies, Las Casas pursued further education in the moral and juridical conceptions of just war, which he then used in an attempt to defend native peoples from such unjust conquests as Protector of the Indians.[3]

The Spanish Conquests raised a variety of moral concerns for the government at the time regarding colonization, war, unjust conquests, and religion. Bartolomé de las Casas notoriously contradicts himself in the documentation of his beliefs. Las Casas believed that war was “a pestilence and an atrocious calamity for the human race,” yet sometimes it could still be justified. His understanding was that there were many contexts in which war could be justified. Still, the wars of the New World did not fit these contexts Las Casas based many of his ideas on previous historians and philosophers such as Aristotle, Juan Gínes de Sepúlveda, and Gratian. Bartolomé de las Casas rejected Sepúlveda’s view, which supported that of Aristotle’s, of Indians as barbarians, or “natural slaves against whom a just war could be waged”.[3] Las Casas also rejects Sepúlveda’s claim that a just war could be waged to eradicate the Indians’ barbaric customs and argues that this argument could only be applied to an individual subject to Christian rulers – the Indians were therefore protected as Indians were never viewed in any way as living under the jurisdiction of the Crown.[3]

Juan de Zumárraga

Fray Juan de Zumárraga was appointed as Protector of the Indians on January 2, 1528.[2] Authority was given to Zumárraga as the Protector allowing them to pass judgment on crimes committed against the Indians, including punishments. However, the Protector lacked the necessary police force to inflict such punishments; orders were given to the required authorities to successfully carry out decisions regarding transgressors.

Zumárraga proposed in 1529 to appoint a trusted group of secular officials from different religious orders to be elected as such protectors and intervene in Indian civil and criminal cases. However, the Crown would not yield to the regular clergy full sovereignty over the indigenous population and, in 1530, decreed that all issues regarding the natives were to be handled by government officers elected by the local Audiencia.[8]

A scholarly article by Chauvet (1949) provides an account of the authority granted to Zumárraga as Protector of the Indians. These duties included but were not necessarily limited to exercising solitude when looking after and visiting said Indians, to see that the Indians were well treated, and taught in matters of the Holy Catholic Church.[2] All interactions with the native populations of the Spanish colonies were to be conducted with kind treatment and conversion. The same journal states that the Audiencia was under the orders to give and to be given all the support and aid that Zumárraga should ask of them.[2]

On September 29, 1534, Zumárraga was relieved of his duties as protector of the Indians after appealing to resign.[2]

Legislation

The lack of legislation and official recognition produced many difficulties when trying to define the roles of the Protector of the Indians. It wasn't until the publication of the New Laws in 1542 that there was an official prohibition of the enslavement of native peoples with added provisions for the gradual abolition of the encomienda system.

The first provisions directly addressing the Protector de Indios as such are first known to appear in the Cedulario Indiano compiled by Encina Diego in 1596,[9] and later in the Compilation of the Laws of the Indies, Volume II, Book VI, Title V.[10] Other related provisions within the Laws refer to the treatment of the Indian subjects, their conversion to Christianity via evangelization[11] and the good care of their lives, with specific instructions to not oppress them in any way and to regard them as vassals of the Crown. It also required from the prosecutor of the local Audiencia to watch over the treatment given to the natives by colonial representatives with the obligation to punish any violation of the law and notify the Council of the Indies.

The term Audiencia is defined by the universal Merriam-Webster dictionary as a high court of justice in a Spanish colony frequently exercising military power as well as judicial and political functions. The Audiencia was established to act as a royal court which assisted Juan de Zumárraga in the policing and infliction of punishment of transgressors.

On April 9, 1591 the Crown issued a Royal Decree and a letter to Luis de Velasco, viceroy of New Spain, that laid down the legal basis for the creation of a specific agency dedicated to the defense of the natives in the colonies. The office was to be headed by an attorney general and a consultant to the legal procedures involving natives.[12]

Aftermath

There is little documentation of the Protector of the Indians following the repeal of Fray Juan de Zumárraga. As the Spanish Constitution of 1812 became integral, the Protectoría de indios was dismantled. Though it was temporarily restored following the Trienio Liberal, it disappeared completely from the American colonies after their independence, leaving the indigenous population subject to a completely different legal status.

References

- A., Clayton, Lawrence (2012). Bartolomé de las Casas : a biography. Cambridge University Press. OCLC 785865283.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Chauvet, Fidel de J. (1949). "Fray Juan de Zumárraga, Protector of the Indians". The Americas. 5 (3): 283–295. doi:10.2307/977658. ISSN 0003-1615. JSTOR 977658. S2CID 144899285.

- Orique O.P., David Thomas; Roldán-Figueroa, Rady (2019-01-01). Bartolomé de las Casas, O.P.: History, Philosophy, and Theology in the Age of European Expansion. BRILL. doi:10.1163/9789004387669_010. ISBN 978-90-04-36973-3. S2CID 239818750.

- Novoa, Mauricio (2016). The protectors of Indians in the Royal Audience of Lima : history, careers and legal culture, 1575-1775. Leiden. ISBN 978-90-04-30517-5. OCLC 929864181.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Schmitz, Timothy J. (2006-07-01). "The Spanish Hieronymites and the Reformed Texts of the Council of Trent". The Sixteenth Century Journal. 37 (2): 375–399. doi:10.2307/20477841. JSTOR 20477841.

- Bayle, Constantino (1948). El protector de indios. Sevilla: Escuela de Estudios Hispano-Americanos, 1945. pp. 12–13.

- Bartolomé de las Casas, The Devastation of the Indies: A Brief Account, trans. Herma Briffault (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1992), 32-35, 40-41.

- Bayle, Constantino (1948). El protector de indios. Sevilla: Escuela de Estudios Hispano-Americanos, 1945. p. 7.

- Lemoine, René Martínez (January 2003). "The classical model of the Spanish-American colonial city". The Journal of Architecture. 8 (3): 355–368. doi:10.1080/1360236032000134844. ISSN 1360-2365. S2CID 144190934.

- Office., Arizona. Surveyor General's (1880). Compilation of the laws, regulations, usages and conditions of Spain and Mexico under which lands were granted and held, missions, presidios and pueblos established and governed. [Govt. Print. Off.?]. OCLC 647102908.

- "Las Casas and the Concept of Just War", Bartolomé de las Casas, O.P., BRILL, pp. 218–242, 2018-11-20, doi:10.1163/9789004387669_010, ISBN 9789004369733, S2CID 239818750, retrieved 2022-10-07

- Borah, Woodrow (1985). El Juzgado General de Indios en la Nueva España. México: Fondo de Cultura Económica. p. 137. ISBN 968-16-1749-5.

Bibliography

- Cutter, Charles R. 1986. The protector de indios in colonial New Mexico, 1659-1821. University of New Mexico Press.

- Ruigómez Gómez, Carmen. 1988. "Una política indigenista de los Habsburgo: el protector de indios en el Perú" Madrid: Instituto de cooperación iberoamericana. ICI,

- Curiel, José Refugio de la Torre. 2010. Un mecenazgo fronterizo: El protector de indios Juan de Gándara y los ópatas de Opodepe (Sonora) a principios del siglo XIX Revista de Indias, Vol 70, No 248 (2010)

- Martín, Ascensión Baeza. 2010. Presión e intereses en torno al cargo de protector general de indios del Nuevo Reino de León: el caso de Nicolás de Villalobos, 1714-1734. Anuario de Estudios Americanos, Vol 67, No 1 (2010):209-237

- Ellsberg, Robert November 5, 2012. Las Casas' Discovery: What the 'Protector of the Indians' found in America.