Olm

The olm or proteus (Proteus anguinus) is an aquatic salamander which is the only species in the genus Proteus of the family Proteidae[2] and the only exclusively cave-dwelling chordate species found in Europe; the family's other extant genus is Necturus. In contrast to most amphibians, it is entirely aquatic, eating, sleeping, and breeding underwater. Living in caves found in the Dinaric Alps, it is endemic to the waters that flow underground through the extensive limestone bedrock of the karst of Central and Southeastern Europe in the basin of the Soča River (Italian: Isonzo) near Trieste, Italy, southwestern Croatia, and Bosnia and Herzegovina.[3] Introduced populations are found near Vicenza, Italy, and Kranj, Slovenia.[4] It was first mentioned in 1689 by the local naturalist Valvasor in his Glory of the Duchy of Carniola, who reported that, after heavy rains, the olms were washed up from the underground waters and were believed by local people to be a cave dragon's offspring.

| Olm | |

|---|---|

| |

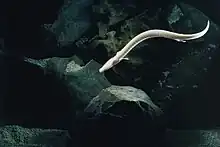

| Olms in Postojna Cave, Slovenia | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Amphibia |

| Order: | Urodela |

| Family: | Proteidae |

| Genus: | Proteus Laurenti, 1768 |

| Species: | P. anguinus |

| Binomial name | |

| Proteus anguinus Laurenti, 1768 | |

| Subspecies | |

| |

| Native range[lower-alpha 1] | |

This cave salamander is most notable for its adaptations to a life of complete darkness in its underground habitat. The olm's eyes are undeveloped, leaving it blind, while its other senses, particularly those of smell and hearing, are acutely developed. Most populations also lack any pigmentation in their skin. The olm has three toes on its forelimbs, but only two toes on its hind feet. It exhibits neoteny, retaining larval characteristics like external gills into adulthood,[5] like some American amphibians, the axolotl and the mudpuppies (Necturus).

Etymology

The word olm is a German loanword that was incorporated into English in the late 19th century.[6] The origin of the German Olm or Grottenolm 'cave olm', is unclear.[7][8] It may be a variant of the word Molch 'salamander'.[7][9]

Common names

It is also called the "human fish" by locals because of its fleshy skin color (translated literally from Slovene: človeška ribica, Macedonian: човечка рипка, Croatian: čovječja ribica, Bosnian: čovječija ribica Serbian: човечја рибица), as well as "cave salamander" or "white salamander".[10] In Slovenia, it is called močeril (from *močerъ 'earthworm, damp creepy-crawly'; moča 'dampness').[11][12]

Description

External appearance

The olm's body is snakelike, 20–30 cm (8–12 in) long, with some specimens reaching up to 40 centimetres (16 in), which makes them some of the largest cave-dwelling animals in the world.[13][14] The average length is between 23 and 25 cm.[15] Females grow larger than males, but otherwise the primary external difference between the sexes is in the cloaca region (shape and size) when breeding.[4] The trunk is cylindrical, uniformly thick, and segmented with regularly spaced furrows at the myomere borders. The tail is relatively short, laterally flattened, and surrounded by a thin fin. The limbs are small and thin, with a reduced number of digits compared to other amphibians: the front legs have three digits instead of the normal four, and the rear have two digits instead of five. Its body is covered by a thin layer of skin, which contains very little of the pigment riboflavin,[16] making it yellowish-white or pink in color.[5]

The white skin color of the olm retains the ability to produce melanin, and will gradually turn dark when exposed to light; in some cases the larvae are also colored. One population, the black olm, is always pigmented and dark brownish to blackish when adult.[17] The olms pear-shaped head ends with a short, dorsoventrally flattened snout. The mouth opening is small, with tiny teeth forming a sieve to keep larger particles inside the mouth. The nostrils are so small as to be imperceptible, but are placed somewhat laterally near the end of the snout. The regressed eyes are covered by a layer of skin. The olm breathes with external gills that form two branched tufts at the back of the head.[5] They are red in color because the oxygen-rich blood shows through the non-pigmented skin.[8] The olm also has rudimentary lungs, but their role in respiration is only accessory, except during hypoxic conditions.[4]

Sensory organs

Cave-dwelling animals have been prompted, among other adaptations, to develop and improve non-visual sensory systems in order to orient in and adapt to permanently dark habitats.[18] The olm's sensory system is also adapted to life in the subterranean aquatic environment. Unable to use vision for orientation, the olm compensates with other senses, which are better developed than in amphibians living on the surface. It retains larval proportions, like a long, slender body and a large, flattened head, and is thus able to carry a larger number of sensory receptors.[19]

Photoreceptors

Although blind, the olm swims away from light.[8] The eyes are regressed, but retain sensitivity. They lie deep below the dermis of the skin and are rarely visible except in some younger adults. Larvae have normal eyes, but development soon stops and they start regressing, finally atrophying after four months of development.[20] The pineal body also has photoreceptive cells which, though regressed, retain visual pigment like the photoreceptive cells of the regressed eye. The pineal gland in Proteus probably possesses some control over the physiological processes.[21] Behavioral experiments revealed that the skin itself is also sensitive to light.[22] Photosensitivity of the integument is due to the pigment melanopsin inside specialized cells called melanophores. Preliminary immunocytochemical analyses support the existence of photosensitive pigment also in the animal's integument.[23][24]

Chemoreceptors

The olm is capable of sensing very low concentrations of organic compounds in the water. They are better at sensing both the quantity and quality of prey by smell than related amphibians.[25] The nasal epithelium, located on the inner surface of the nasal cavity and in the Jacobson's organ, is thicker than in other amphibians.[26] The taste buds are in the mucous epithelium of the mouth, most of them on the upper side of the tongue and on the entrance to the gill cavities. Those in the oral cavity are used for tasting food, where those near the gills probably sense chemicals in the surrounding water.[27]

Mechano- and electroreceptors

The sensory epithelia of the inner ear are very specifically differentiated, enabling the olm to receive sound waves in the water, as well as vibrations from the ground. The complex functional-morphological orientation of the sensory cells enables the animal to register the sound sources.[28][29] As this animal stays neotenic throughout its long life span, it is only occasionally exposed to normal adult hearing in air, which is probably also possible for Proteus as in most salamanders. Hence, it would be of adaptive value in caves, with no vision available, to profit from underwater hearing by recognizing particular sounds and eventual localization of prey or other sound sources, i.e. acoustical orientation in general. Behavioural (ethological) tests have shown that its sensitivity for detecting underwater sound waves reaches into the area of frequencies of sound waves between 10 and more than 12,000 Hz, while the greatest sensitivity is reached between 1,500 and 2,000 Hz.The ethological experiments indicate that the best hearing sensitivity of Proteus is between 10 Hz and up to 12,000 Hz.[30] The lateral line supplements inner ear sensitivity by registering low-frequency nearby water displacements.[18][30]

A new type of electroreception sensory organ has been analyzed on the head of Proteus, utilizing light and electron microscopy. These new organs have been described as ampullary organs.[31]

Like some other lower vertebrates, the olm has the ability to register weak electric fields.[19] Some behavioral experiments suggest that the olm may be able to use Earth's magnetic field to orient itself. In 2002, Proteus anguinus was found to align itself with natural and artificially modified magnetic fields.[32]

Ecology and life history

The olm lives in well-oxygenated underground waters with a typical, very stable temperature of 8–11 °C (46–52 °F), infrequently as warm as 14 °C (57 °F).[4] The black olm may occur in surface waters that are somewhat warmer.[4]

The olm swims by eel-like twisting of its body, assisted only slightly by its poorly developed legs. It is a predatory animal, feeding on small crustaceans (for example, Troglocaris shrimp, Niphargus, Asellus and Synurella amphipods and Oniscus asellus), snails (for example, Belgrandiella) and occasionally insects and insect larvae (for example, Trichoptera, Ephemeroptera, Plecoptera and Diptera).[5][33][34][35] It does not chew its food, instead swallowing it whole. The olm is resistant to long-term starvation, an adaptation to its underground habitat. It can consume large amounts of food at once, and store nutrients as large deposits of lipids and glycogen in the liver. When food is scarce, it reduces its activity and metabolic rate, and can also reabsorb its own tissues in severe cases. Controlled experiments have shown that an olm can survive up to 10 years without food.[36]

Olms are gregarious, and usually aggregate either under stones or in fissures.[37] Sexually active males are an exception, establishing and defending territories where they attract females. The scarcity of food makes fighting energetically costly, so encounters between males usually only involve display. This is a behavioral adaptation to life underground.[38]

Breeding and longevity

Reproduction has only been observed in captivity so far.[38][39] Sexually mature males have swollen cloacas, brighter skin color, two lines at the side of the tail, and slightly curled fins. No such changes have been observed in the females. The male can start courtship even without the presence of a female. He chases other males away from the chosen area, and may then secrete a female-attracting pheromone. When the female approaches, he starts to circle around her and fan her with his tail. Then he starts to touch the female's body with his snout, and the female touches his cloaca with her snout. At that point, he starts to move forward with a twitching motion, and the female follows. He then deposits the spermatophore, and the animals keep moving forward until the female hits it with her cloaca, after which she stops and stands still. The spermatophore sticks to her and the sperm cells swim inside her cloaca, where they attempt to fertilize her eggs. The courtship ritual can be repeated several times over a couple of hours.[38]

The female lays up to 70 eggs, each about 12 millimetres (0.5 in) in diameter, and places them between rocks, where they remain under her protection.[40] The average is 35 eggs and the adult female typically breeds every 12.5 years.[41] The tadpoles are 2 centimetres (0.8 in) long when they hatch and live on yolk stored in the cells of the digestive tract for a month.[40]

At a temperature of 10 °C (50 °F), the olm's embryonic development (time in the eggs before hatching) is 140 days, but it is somewhat slower in colder water and faster in warmer, being as little as 86 days at 15 °C (59 °F). After hatching, it takes another 14 years to reach sexual maturity if living in water that is 10 °C (50 °F).[4][42] The larvae gain adult appearance after nearly four months, with the duration of development strongly correlating with water temperature.[42] Unconfirmed historical observations of viviparity exist, but it has been shown that the females possess a gland that produces the egg casing, similar to those of fish and egg-laying amphibians.[38] Paul Kammerer reported that female olm gave birth to live young in water at or below 13 °C (55 °F) and laid eggs at higher,[8] but rigorous observations have not confirmed that. The olm appears to be exclusively oviparous.[43]

Development of the olm and other troglobite amphibians is characterized by heterochrony – the animal does not undergo metamorphosis and instead retains larval features. The form of heterochrony in the olm is neoteny – delayed somatic maturity with precocious reproductive maturity, i.e. reproductive maturity is reached while retaining the larval external morphology. In other amphibians, the metamorphosis is regulated by the hormone thyroxine, secreted by the thyroid gland. The thyroid is normally developed and functioning in the olm, so the lack of metamorphosis is due to the unresponsiveness of key tissues to thyroxine.[21]

Longevity is estimated at up to 58 years.[44] A study published in Biology Letters estimated that they have a maximum lifespan of over 100 years and that the lifespan of an average adult is around 68.5 years. When compared to the longevity and body mass of other amphibians, olms are outliers, living longer than would be predicted from their size.[41]

Taxonomic history

Olms from different cave systems differ substantially in body measurements, color and some microscopic characteristics. Earlier researchers used these differences to support the division into five species, while modern herpetologists understand that external morphology is not reliable for amphibian systematics and can be extremely variable, depending on nourishment, illness, and other factors; even varying among individuals in a single population. Proteus anguinus is now considered a single species. The length of the head is the most obvious difference between the various populations – individuals from Stična, Slovenia, have shorter heads on average than those from Tržič, Slovenia, and the Istrian peninsula, for example.[45]

Black olm

The black olm (Proteus anguinus parkelj Sket & Arntzen, 1994) is the only other recognized subspecies of the olm. It is endemic to the underground waters near Črnomelj, Slovenia, an area smaller than 100 square kilometres (39 sq mi). It was first found in 1986 by members of the Slovenian Karst Research Institute, who were exploring the water from Dobličica karst spring in the White Carniola region.[46]

It has several features separating it from the nominotypical subspecies (Proteus a. anguinus):[17]

| Feature | Proteus anguinus anguinus | Proteus anguinus parkelj | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Skin | Not pigmented. | Normally pigmented, dark brown, or black in color. | The most obvious difference. |

| Head shape | Long, slender. | Shorter, equally thick. Stronger jaw muscles visible as two bulbs on the top of the head. | |

| Body length | Shorter, 29–32 vertebrae. | Longer, 34–35 vertebrae. | Amphibians do not have a fixed number of vertebrae. |

| Appendages | Longer. | Shorter. | |

| Tail | Longer in proportion to the rest of the body. | Shorter in proportion. | |

| Eyes | Regressed. | Almost normally developed, although still small compared to other amphibians. Covered by a thin layer of transparent skin, no eyelids. | Regressed eye of White Proteus shows first of all immunolabelling for the red-sensitive cone opsin. The eye of Black Proteus has principal rods, red-sensitive cones and blue- or UV- sensitive cones. |

| Other senses | Specific and highly sensitive. | Some sensory organs, particularly electroreceptors, less sensitive. | Not very obvious. |

Proteus bavaricus

The debated species Proteus bavaricus is a close relative of the olm.[47] The species was described from a single bone, by George Brunner, and the holotype is housed in his private collection.[48][49] It was found in Bavaria's Devil's Cave, in the Pleistocene layer.[49] In his 1998 book, J. Alan Hollman described the species as a "problematic" taxon, saying that Brunner's drawing of the bone does not adequately show the differences between P. bavaricus and P. anguinus.[49]

Research history

The first written mention of the olm is in Johann Weikhard von Valvasor's The Glory of the Duchy of Carniola (1689) as a baby dragon. Heavy rains of Slovenia would wash the olms up from their subterranean habitat, giving rise to the folklore belief that great dragons lived beneath the Earth's crust, and the olms were the undeveloped offspring of these mythical beasts. In his book Valvasor compiled the local Slovenian folk stories and pieced together the rich mythology of the creature and documented observations of the olm as "Barely a span long, akin to a lizard, in short, a worm and vermin of which there are many hereabouts". [8][50]

The first researcher to retrieve a live olm was a physician and researcher from Idrija, Giovanni Antonio Scopoli, who sent dead specimens and drawings to colleagues and collectors. Josephus Nicolaus Laurenti, though, was the first to briefly describe the olm in 1768 and give it the scientific name Proteus anguinus. It was not until the end of the century that Carl Franz Anton Ritter von Schreibers from the Naturhistorisches Museum of Vienna started to look into this animal's anatomy. The specimens were sent to him by Sigmund Zois. Schreibers presented his findings in 1801 to The Royal Society in London, and later also in Paris. Soon, the olm started to gain wide recognition and attract significant attention, resulting in thousands of animals being sent to researchers and collectors worldwide. A Dr Edwards was quoted in a book of 1839 as believing that "...the Proteus Anguinis is the first stage of an animal prevented from growing to perfection by inhabiting the subterraneous waters of Carniola."[51]

In 1880 Marie von Chauvin began the first long-term study of olms in captivity. She learned that they detected prey's motion, panicked when a heavy object was dropped near their habitat, and developed color if exposed to weak light for a few hours a day, but could not cause them to change to a land-dwelling adult form, as she and others had done with axolotl.[8]

The basis of functional morphological investigations in Slovenia was set up by Lili Istenič in the 1980s. More than twenty years later, the Research Group for functional morphological Studies of the Vertebrates in the Department of Biology (Biotechnical Faculty, University of Ljubljana), is one of the leading groups studying the olm under the guidance of Boris Bulog.[52] There are also several cave laboratories in Europe in which olms have been introduced and are being studied. These are Moulis, Ariège (France), Choranche cave (France), Han-sur-Lesse (Belgium) and Aggtelek (Hungary). They were also introduced into the Hermannshöhle (Germany) and Oliero (Italy) caves, where they still live today.[53][54] Additionally, there is evidence that a small number of olms were introduced to the United Kingdom in the 1940s, although it's highly likely that the animals perished shortly after being released.[55]

The olm was used by Charles Darwin in his seminal work On the Origin of Species as an example for the reduction of structures through disuse:[56]

Far from feeling surprise that some of the cave-animals should be very anomalous...as is the case with blind Proteus with reference to the reptiles of Europe, I am only surprised that more wrecks of ancient life have not been preserved, owing to the less severe competition to which the scanty inhabitants of these dark abodes will have been exposed.

An olm (Proteus) genome project is currently underway by the University of Ljubljana and BGI. With an estimated genome size roughly 15-times the size of human genome, this will likely be the largest animal genome sequenced so far.[57]

Conservation

The olm is extremely vulnerable to changes in its environment, due to its adaptation to the specific conditions in caves. Water resources in the karst are extremely sensitive to all kinds of pollution.[58] The contamination of the karst underground waters is due to the large number of waste disposal sites leached by rainwater, as well as to the accidental overflow of various liquids. The reflection of such pollution in the karst underground waters depends on the type and quantity of pollutants, and on the rock structure through which the waters penetrate. Self-purification processes in the underground waters are not completely understood, but they are quite different from those in surface waters.[59]

Among the most serious chemical pollutants are chlorinated hydrocarbon pesticides, fertilizers, polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs), which are or were used in a variety of industrial processes and in the manufacture of many kinds of materials; and metals such as mercury, lead, cadmium, and arsenic. All of these substances persist in the environment, being slowly, if at all, degraded by natural processes. In addition, all are toxic to life if they accumulate in any appreciable quantity.[59] The olm is nevertheless noted for its capability of surviving higer concentrations of accumulated PCBs than related aquatic organisms.[60]

The olm was included in annexes II and IV of the 1992 EU Habitats Directive (92/43/EEC). The list of species in annex II, combined with the habitats listed in annex I, is used by individual countries to designate protected areas known as 'Special Areas of Conservation'. These areas, combined with others created by the older Birds Directive were to form the Natura 2000 network. Annex IV additionally lists "animal and plant species of community interest in need of strict protection", although this has little legal ramifications.[61] Areas inhabited by the olm were eventually included in the Slovenian, Italian and Croatian parts of the Natura 2000 network.[62]

The olm was first protected in Slovenia in 1922 along with all cave fauna, but the protection was not effective and a substantial black market came into existence. In 1982 it was placed on a list of rare and endangered species. This list also had the effect of prohibiting trade of the species. After joining the European Union in 2004, Slovenia had to establish mechanisms for protection of the species included in the EU Habitats Directive. The olm is included in a Slovenian Red list of endangered species, thus its capturing or killing is allowed only under specific circumstances determined by the local authorities (e.g. scientific study).[63]

In Croatia, the olm is protected by the legislation designed to protect amphibians – collecting is possible only for research purposes by permission of the National Administration for Nature and Environment Protection.[64] As of 2020 the Croatian population has been assessed as 'critically endangered' in Croatia.[65] As of 1999, the environmental laws in Bosnia and Herzegovina and Montenegro had not yet been clarified for this species.

In the 1980s the IUCN claimed that some illegal collection of this species for the pet trade took place, but that the extent of this was unknown: this text has been copied into subsequent assessments, but by now the anecdotic claims are not considered to be indicative of a major threat. Since the 1980s until the most recent assessment in 2022 the organisation has rated the conservation status for the IUCN Red List as 'vulnerable', this because of its natural distribution being fragmented over a number of cave systems as opposed to being continuous, and what they consider a decline in extent and quality of its habitat, which they assume means that the population has been decreasing for the last 40 years.[1]

Zagreb Zoo in Croatia houses the olm.[65][66][67] Historically, olms were kept in several zoos in Germany, as well as in Belgium, the Netherlands, Slovenia and the United Kingdom. At present they can only be experienced at Zagreb Zoo, Hermannshöhle in Germany and Vivarium Proteus (Proteus Vivarium) within Postojnska jama (Postojna Cave) in Slovenia.[68] There are also captive breeding programs in places like France.[69]

Cultural significance

The olm is a symbol of Slovenian natural heritage. The enthusiasm of scientists and the broader public about this inhabitant of Slovenian caves is still strong 300 years after its discovery. Postojna Cave is one of the birthplaces of biospeleology due to the olm and other rare cave inhabitants, such as the blind cave beetle. The image of the olm contributes significantly to the fame of Postojna Cave, which Slovenia successfully utilizes for the promotion of ecotourism in Postojna and other parts of Slovenian karst. Tours of Postojna Cave also include a tour around the speleobiological station – the Proteus vivarium, showing different aspects of the cave environment.[70]

The olm was also depicted on one of the Slovenian tolar coins.[71] It was also the namesake of Proteus, the oldest Slovenian popular science magazine, first published in 1933.[72]

Notes

- Assuming contiguous inhabitance. According to newer assessments, the range is fragmented to smaller areas within the marked area.[1]

References

- IUCN SSC Amphibian Specialist Group (2022). "Proteus anguinus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2022: e.T18377A89698593. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2022-2.RLTS.T18377A89698593.en. Retrieved 6 August 2023.

- Frost, Darrel R. (2023) [1998]. "Proteus Laurenti, 1768". Amphibian Species of the World. American Museum of Natural History. Retrieved 19 March 2023.

- Sket, Boris (1997). "Distribution of Proteus (Amphibia: Urodela: Proteidae) and its possible explanation". Journal of Biogeography. 24 (3): 263–280. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2699.1997.00103.x. S2CID 84308933.

- Bulog, Boris; van der Meijden, Arie (26 December 1999). "Proteus anguinus". AmphibiaWeb. Retrieved 27 January 2014.

- Burnie D.; Wilson D.E., eds. (2001). Animal. London: DK. pp. 61, 435. ISBN 0-7894-7764-5.

- "olm". Oxford Dictionaries. Archived from the original on March 15, 2013. Retrieved 2015-12-09.

- Seebold, Elmar (1999), Kluge Etymologisches Wörterbuch der deutschen Sprache [Kluge's Etymological Dictionary of the German Language] (in German) (23rd ed.), Berlin: Walter de Gruyter, p. 601

- Ley, Willy (February 1968). "Epitaph for a Lonely Olm". For Your Information. Galaxy Science Fiction. pp. 95–104.

- "Olm". Digitale Wörterbuch der deutschen Sprache (in German). Retrieved 2015-12-09.

- "Olm". nhm.ac.uk. Natural History Museum, London. Retrieved 2013-07-15.

- Snoj, Marko (2003). Slovenski etimološki slovar. Ljubljana: Modrijan. p. 408.

- Bezlaj, France (1982). Etimološki slovar slovenskega jezika, vol. 2. Ljubljana: SAZU. p. 190.

- Weber A. (2000). Fish and amphibia. In: Culver D.C. et al. (ed.): Ecosystems of the world: Subterranean Ecosystems, pp. 109–132. Amsterdam: Elsevier

- How Slovenia is helping its 'baby dragons' - The Guardian

- Blackburn, Daniel G. (2019-07-01). "The oviparous olm: Analysis and refutation of claims for viviparity in the cave salamander Proteus anguinus (Amphibia: Proteidae)". Zoologischer Anzeiger. 281: 16–23. doi:10.1016/j.jcz.2019.05.004. ISSN 0044-5231. S2CID 190885637.

- Istenic L. & Ziegler I. (1974). "Riboflavin as "pigment" in the skin of Proteus anguinus L.". Naturwissenschaften. 61 (12): 686–687. Bibcode:1974NW.....61..686I. doi:10.1007/bf00606524. PMID 4449576. S2CID 28710659.

- Sket, B.; Arntzen, J.W. (1994). "A black, non-troglomorphic amphibian from the karst of Slovenia: Proteus anguinus parkelj n. ssp (Urodela: Proteidae)". Bijdragen tot de Dierkunde. 64: 33–53. doi:10.1163/26660644-06401002.

- Schlegel, P.A.; Briegleb, W.; Bulog, B.; Steinfartz, S. (2006). "Revue et nouvelles données sur la sensitivité a la lumiere et orientation non-visuelle chez Proteus anguinus, Calotriton asper et Desmognathus ochrophaeus (Amphibiens urodeles hypogés)". Bulletin de la Société herpétologique de France (in French). 118: 1–31.

- Schlegel, P.; Bulog, B. (1997). "Population-specific behavioral electrosensitivity of the European blind cave salamander, Proteus anguinus". Journal of Physiology (Paris). 91 (2): 75–79. doi:10.1016/S0928-4257(97)88941-3. PMID 9326735. S2CID 25550328.

- Durand, J.P. (1976). "Ocular Development and Involution in the European Cave Salamander, Proteus Anguinus Laurenti". The Biological Bulletin. 151 (3): 450–466. doi:10.2307/1540499. JSTOR 1540499. PMID 1016662.

- Langecker T.G. (2000). The effects of continuous darkness on cave ecology and cavernicolous evolution. In: Culver D.C. et al. (eds.): Ecosystems of the world: Subterranean Ecosystems, pp. 135–157. Amsterdam: Elsevier

- Hawes, R.S. (1945). "On the eyes and reactions to light of Proteus anguinus". Q. J. Microsc. Sci. New Series. 86: 1–53. PMID 21004249.

- Kos M. (2000). Imunocitokemijska analiza vidnih pigmentov v čutilnih celicah očesa in pinealnega organa močerila (Proteus anguinus, Amphibia, Urodela) (Immunocitochemical analysis of the visual pigments in the sensory cells of the eye and the pineal organ of the olm (Proteus anguinus, Amphibia, Urodela).) PhD thesis. Ljubljana: University of Ljubljana. (in Slovene)

- Kos, M.; Bulog, B.; et al. (2001). "Immunocytochemical demonstration of visual pigments in the degenerate retinal and pineal photoreceptors of the blind cave salamander (Proteus anguinus)". Cell Tissue Res. 303 (1): 15–25. doi:10.1007/s004410000298. PMID 11236001. S2CID 30951738.

- Hüpop K. (2000). How do cave animals cope with the food scarcity in caves?. In: Culver D.C. et al. (ed.): Ecosystems of the world: Subterranean Ecosystems, pp. 159–188. Amsterdam: Elsevier

- Dumas, P (1998). "The olfaction in Proteus anguinus". Behavioural Processes. 43 (2): 107–113. doi:10.1016/s0376-6357(98)00002-3. PMID 24895999. S2CID 20825148.

- Istenič, L.; Bulog, B. (1979). "The structural differentiations of the buccal and pharyngeal mucous membrane of the Proteus anguinus Laur". Biološki Vestnik. 27: 1–12.

- Bulog, B (1989). "Differentiation of the inner ear sensory epithelia of Proteus anguinus (Urodela, Amphibia)". Journal of Morphology. 202 (3): 325–338. doi:10.1002/jmor.1052020303. PMID 29865674. S2CID 46928861.

- Bulog B. (1990). Čutilni organi oktavolateralnega sistema pri proteju Proteus anguinus (Urodela, Amphibia). I. Otični labirint (Sense organs of the octavolateral system in proteus Proteus anguinus (Urodela, Amphibia). I. Otic labyrinth). Biološki vestnik 38: 1–16 (in Slovene)

- Bulog B. & Schlegel P. (2000). Functional morphology of the inner ear and underwater audiograms of Proteus anguinus (Amphibia, Urodela). Pflügers Arch 439(3), suppl., pp. R165–R167.

- Istenič, L.; Bulog, B. (1984). "Some evidence for the ampullary organs in the European cave salamander Proteus anguinus (Urodela, Amphibia)". Cell Tissue Res. 235 (2): 393–402. doi:10.1007/bf00217865. PMID 6705040. S2CID 25511603.

- Bulog B., Schlegel P. et al. (2002). Non-visual orientation and light-sensitivity in the blind cave salamander, Proteus anguinus (Amphibia, Caudata). In: Latella L., Mezzanotte E., Tarocco M. (eds.). 16th international symposium of biospeleology; 2002 Sep 8–15; Verona: Societé Internationale de Biospéologie, pp. 31–32.

- Jugovic E.; J.E. Praprotnik; V. Buzan; M. Lužnik (2015). "Estimating population size of the cave shrimp Troglocaris anophthalmus (Crustacea, Decapoda, Caridea) using mark–release–recapture data". Animal Biodiversity and Conservation. 38 (1): 77–86. doi:10.32800/abc.2015.38.0077.

- Meaton, J. (2011). "Proteus anguinus". Animal Diversity Web. Retrieved 1 January 2023.

- "Proteus anguinus". AmphibiaWeb. 2021.

- Bulog B. (1994). Dve desetletji funkcionalno-morfoloških raziskav pri močerilu (Proteus anguinus, Amphibia, Caudata) (Two decades of functional-morphological research on the olm (Proteus anguinus, Amphibia, Caudata)). Acta Carsologica XXIII/19. (in Slovene)

- Guillaume, O (2000). "Role of chemical communication and behavioural interactions among conspecifics in the choice of shelters by the cave-dwelling salamander Proteus anguinus (Caudata, Proteidae)". Can. J. Zool. 78 (2): 167–173. doi:10.1139/z99-198.

- Aljančič M., Bulog B. et al. (1993). Proteus – mysterious ruler of Karst darkness. Ljubljana: Vitrium d.o.o. (in Slovene)

- Aljančič, Gregor (2019-07-25). "History of research on Proteus anguinus Laurenti 1768 in Slovenia". Folia Biologica et Geologica. 60 (1): 39. doi:10.3986/fbg0050.

- Aljančič G. and Aljančič M. (1998). Žival meseca oktobra: Človeška ribica (Proteus anguinus) (The animal of the month of October: olm). Proteus 61(2): 83–87 (in Slovene)

- Voituron, Y.; De Fraipont, M.; Issartel, J.; Guillaume, O.; Clobert, J. (2010). "Extreme lifespan of the human fish (Proteus anguinus): a challenge for ageing mechanisms". Biology Letters. 7 (1): 105–107. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2010.0539. PMC 3030882. PMID 20659920.

- Durand, J.P.; Delay, B. (1981). "Influence of temperature on the development of Proteus anguinus (Caudata: Proteidae) and relation with its habitat in the subterranean world". Journal of Thermal Biology. 6 (1): 53–57. doi:10.1016/0306-4565(81)90044-9.

- Sever, David M., ed. (2003). Reproductive biology and phylogeny of Urodela. Science Publishers. p. 449. ISBN 1578082854.

- Noellert A., Noellert C. (1992). Die Aphibien Europas. Franckh-Kosmos Verlags GmbH & co., Stuttgart.(in German)

- Arntzen, J.W.; Sket, Boris (1997). "Morphometric analysis of black and white European cave salamanders, Proteus anguinus". Journal of Zoology. 241 (4): 699–707. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7998.1997.tb05742.x.

- Sket B. et al. (ed.) (2003). Živalstvo Slovenije (The animals of Slovenia). Ljubljana: Tehniška založba Slovenije. ISBN 86-365-0410-4 (in Slovene)

- Macaluso, Loredana; Villa, Andrea; Mörs, Thomas (2022). Mannion, Philip (ed.). "A new proteid salamander (Urodela, Proteidae) from the middle Miocene of Hambach (Germany) and implications for the evolution of the family". Palaeontology. 65 (1). doi:10.1111/pala.12585. ISSN 0031-0239.

- Handbuch der Paläoherpetologie: Encyclopedia of paleoherpetology. G. Fischer. 1981. ISBN 978-3-437-30339-5.

- Holman, J. Alan (1998-06-18). Pleistocene Amphibians and Reptiles in Britain and Europe. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-535466-9.

- Baker, Nick. "The Dragon of Vrhnika – The Olm". Nickbaker.tv. Archived from the original on 2009-12-12. Retrieved 2009-12-05.

- Millingen, J. G. (1839). Curiosities of Medical Experience (2nd ed.). London: Richard Bentley. ISBN 9781465521750. Retrieved 8 March 2018.

- Bulog B. et al. (2003). Black Proteus: mysterious dweller of the Karst in Bela krajina. Ljubljana: TV Slovenia, Video tape.

- Grosse, Wolf-Rüdiger (2004). "Grottenolm – Proteus anguinus Laurenti, 1768". In Frank Meyer; et al. (eds.). Die Lurche und Kriechtiere Sachsen-Anhalts. Bielefeld: Laurenti-Verlag. pp. 191–193. ISBN 3-933066-17-4.

- Bonato, Lucio; Fracasso, Giancarlo; Pollo, Roberto; Richard, Jacopo; Semenzato, Massimo (2007). "Proteo". Atlante degli anfibi e dei rettili del Veneto. Nuova Dimensione Edizioni. pp. 71–73. ISBN 9788889100400.

- Lewarne, Brian; Allain, Steven J. R. (2020). "The unnatural history of cave olms Proteus anguinus in England". Herpetological Bulletin. 154 (154, Winter 2020): 18–19. doi:10.33256/hb154.1819.

- Darwin C. (1859). On the origin of species by means of natural selection, or the preservation of favoured races in the struggle for life. London: John Murray.

- "Home". Proteus genome project. Retrieved 2020-01-29.

- Bulog, B.; Mihajl, K.; et al. (2002). "Trace element concentrations in the tissues of Proteus anguinus (Amphibia, Caudata) and the surrounding environment". Water, Air, & Soil Pollution. 136 (1–4): 147–163. doi:10.1023/A:1015248110142. S2CID 55129952.

- Castaño-Sánchez, Andrea; Hose, Grant C.; Reboleira, Ana Sofia P.S. (2020). "Ecotoxicological effects of anthropogenic stressors in subterranean organisms: A review". Chemosphere. 244: 125422. doi:10.1016/j.chemosphere.2019.125422.

- Pezdirc, Marko; Heath, Ester; Bizjak Mali, Lilijana; Bulog, Boris (2011). "PCB accumulation and tissue distribution in cave salamander (Proteus anguinus anguinus, Amphibia, Urodela) in the polluted karstic hinterland of the Krupa River, Slovenia". Chemosphere. 84 (7): 987–993. doi:10.1016/j.chemosphere.2011.05.026.

- Habitats directive (1992) ec.europa.eu

- "Olm - Proteus anguinus Laurenti, 1768". European Environment Agency. Retrieved 2023-08-19.

- Slovenian official gazette (2002). no. 82, Tuesday 24 September 2002. (in Slovene)

- Državna uprava za zaštitu prirode i okoliša (1999). "Pravilnik o zaštiti vodozemaca". Narodne novine (in Croatian). Retrieved 2009-12-05.

- "Zagreb Zoo only one in the world with two rare species". CroatiaWeek.com (in Croatian). 10 January 2020.

- Hina (10 January 2020). "ZAGREBAČKI ZOOLOŠKI VRT JEDINI JE NA SVIJETU U KOJEM MOŽETE VIDJETI OVE DVIJE ŽIVOTINJE 'Posjetitelje treba poticati na očuvanje njihovih vrsta'". Jutarnji list (in Croatian).

- "ČOVJEČJA RIBICA (Proteus anguinus)". Zoo.hr (in Croatian). Retrieved 16 July 2020.

- "Grottenolm Proteus anguinus LAURENTI, 1768". Zootierliste (in German). Zoologischen Gesellschaft für Arten- und Populationsschutz e.V. Retrieved 3 August 2023.

- Yong, Ed (2010-07-20). "The olm: the blind cave salamander that lives to 100". National Geographic. Archived from the original on 2023-06-07. Retrieved 2023-09-30.

- Destinacija Postojna Archived 2007-09-27 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 7 June 2007.

- Plut-Pregelj, Leopoldina; Rogel, Carole (2010). "Currency". The A to Z of Slovenia. Scarecrow Press. pp. 97–98. ISBN 9781461731757.

- "Proteus". City Library Kranj. Retrieved 2014-01-22.

External links

- EDGE of Existence Olm information

- Flora and Fauna of Caves: Proteus anguinus

- Proteus magazine (in Slovene)

- Slovenian practice example: Human Fish (Proteus anguinus)

- The olm on ARKive – pictures, films

- The olm on the pages of the Slovenian Natural history museum (in Slovene)

- The Global Amphibian Assessment – Proteus anguinus