Vestibule (architecture)

A vestibule (also anteroom, antechamber, or foyer) is a small room leading into a larger space[1] such as a lobby, entrance hall or passage, for the purpose of waiting, withholding the larger space view, reducing heat loss, providing storage space for outdoor clothing, etc. The term applies to structures in both modern and classical architecture since ancient times. In modern architecture, a vestibule is typically a small room next to the outer door and connecting it with the interior of the building. In ancient Roman architecture, a vestibule (Latin: vestibulum) was a partially enclosed area between the interior of the house and the street.

Ancient usage

Ancient Greece

Vestibules were common in ancient Greek temples. Due to the construction techniques available at the time, it was not possible to build large spans. Consequently, many entranceways had two rows of columns that supported the roof and created a distinct space around the entrance.[2]

In ancient Greek houses, the prothyrum was the space just outside the door of a house, which often had an altar to Apollo or a statue, or a laurel tree.[3]

In elaborate houses or palaces, the vestibule could be divided into three parts, the prothyron (πρόθυρον), the thyroreion (θυρωρεῖον, lit. 'porter's lodge'), and the proaulion (προαύλιον).[4]

The vestibule in ancient Greek homes served as a barrier to the outside world, and also added security to discourage unwanted entrance into the home and unwanted glances into the home. The vestibule's alignment at right angles of private interior spaces, and the use of doors and curtains also added security and privacy from the outside. The Classical Period marked a change in the need for privacy in Greek society, which ultimately led to the design and use of vestibules in Greek homes.[5]

.jpg.webp)

Ancient Rome

In ancient Roman architecture, where the term originates, a vestibule (Latin: vestibulum) was a space that was sometimes present between the interior fauces of a building leading to the atrium and the street.[3] Vestibules were common in ancient architecture. A Roman house was typically divided into two different sections: the first front section, or the public part, was introduced with a vestibule. These vestibules contained two rooms, which usually served as waiting rooms or a porters’ lodge where visitors could get directions or information.[6] Upon entering a Roman house or domus, one would have to pass through the vestibule before entering the fauces, which led to the atrium.[7]

The structure was a mixture between a modern hall and porch.

Church architecture

From the 5th century onward, churches of Eastern and Western Christianity utilized vestibules.[8]

In Roman Catholic and some Anglican churches, the vestibule is usually a spacious area which holds church information such as literature, pamphlets, and bulletin announcements, as well as holy water for worshippers.[9] In Orthodox and Byzantine church architecture, the temple antechamber is more commonly referred to as an exonarthex.

In early Christian architecture, the vestibule replaced the more extravagant atrium or quadriporticus in favor of a more simplified area to house the vase of holy water.[6]

Palace architecture

Vestibules are common in palace architecture. The style of vestibule used in Genoa, Italy was transformed from a previously modest design to a more ornamental structure, which satisfied Genoese aristocracy, while becoming an influential transformation for Italian palaces. The Genoese vestibule became a prominent feature of their palace architecture. These vestibules would sometimes include a fountain or large statue. The Genoese vestibule was large and exaggerated, and seemed "rather designed to accommodate a race of giants."[6]

Modern usage

In contemporary usage, a vestibule constitutes an area surrounding the exterior door. It acts as an antechamber between the exterior and the interior structure. Often it connects the doorway to a lobby or hallway. It is the space one occupies once passing the door, but not yet in the main interior of the building.

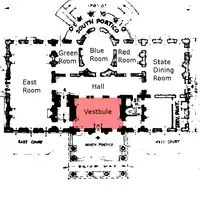

Although vestibules such as a modified mud room are common in private residences, they are especially prevalent in more opulent buildings, such as government ones, designed to elicit a sense of grandeur by contrasting the vestibule's small space with the following greater one, and by adding the aspect of anticipation. The residence of the White House in the United States is such an example. At the north portico, it contains a tiny vestibule[10] between the doors flushed with the outer and inner faces of the exterior wall of, and in the past inside, the Entrance Hall (called incorrectly Vestibule) separated from the not much bigger Cross Hall by just 2 double columns. The difference in sizes between a vestibule and the following space is better illustrated by the—so called—entrance (15) to the main gallery in the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum by Frank Lloyd Wright. Many government buildings mimic the classical architecture from which the vestibule originates.

A purely utilitarian use of vestibules in modern buildings is to create an airlock entry. Such vestibules consist of a set of inner doors and a set of outer doors, the intent being to reduce air infiltration to the building by having only one set of doors open at any given time.

ATM vestibule

An ATM vestibule is an enclosed area with automated teller machines that is attached to the outside of a building, but typically features no further entrance to the building and is not accessible from within. There may be a secure entrance to the vestibule which requires a card to open.[11]

ATM vestibules may also contain security devices, such as panic alarms and CCTV, to help prevent criminal activity.

Railway use

The vestibule on a railway passenger car is an enclosed area at the end of the car body, usually separated from the main part of the interior by a door, which is power-operated on most modern equipment. Entrance to and exit from the car is through the side doors, which lead into the vestibule. When passenger cars are coupled, their vestibules are joined by mating faceplate and diaphragm assemblies to create a weather-tight seal for the safety and comfort of passengers who are stepping from car to car. In British usage the term refers to the part of the carriage where the passenger doors are located; this can be at the ends of the carriage (on long-distance stock) or at the 1⁄4 and 3⁄4 of length positions (typical on modern suburban stock).

Commercial buildings

The U.S. Department of Energy Building Energy Codes Program released a publication on 19 June 2018, which detailed the requirements of a vestibule to be used in commercial buildings. The publication states it requires vestibules to reduce the amount of air that infiltrates a space in order to aid in energy conservation, as well as increasing comfort near entrance doors. By creating an air lock entry, vestibules reduce infiltration losses or gains caused by wind.

Designers of commercial buildings must install a vestibule between the main entry doors leading to spaces that are greater than or equal to 3,000 square feet (280 m2). One other requirement of the design is that it is not necessary for both sets of door to be open in order to pass through the vestibule, and they should have devices that allow for self-closing.[12]

An example of such is in New York City where in the winter, temporary sidewalk vestibules are commonly placed in front of entrances to restaurants to reduce cold drafts from reaching customers inside.[13][14]

See also

- Antarala – Vestibule in certain Hindu temples

- Entryway

- Genkan – Entryway area in Japanese buildings

- Propylaeum – Monumental gateway in Ancient Greek architecture

- Revolving door – Used for similar functions

References

Citations

- Harris 2005.

- Tarbell 1896, p. 81.

- Mollett 1883, p. 267.

- Isambert 1873, p. 771.

- Miles 2016.

- Horton 1874, p. 218.

- McManus 2007.

- Kleinschmidt 1912.

- "Vestibule". catholicculture.org. Retrieved 2018-11-21.

- "White House Residence First Floor History". whitehousemuseum.org. Retrieved 2020-08-31.

- Kovacs 2012.

- "Vestibule Requirements in Commercial Buildings". energycodes.gov. 19 June 2018. Retrieved 31 August 2020.

- Donnelly, Tim (2015-02-20). "In appreciation of the true heroes of the season: winter vestibules". New York Post. Archived from the original on 14 December 2019. Retrieved 2020-10-31.

- McKeever, Amy (2017-01-31). "How Restaurants Literally Stay Warm in Winter". Eater. Archived from the original on 31 October 2020. Retrieved 2020-10-31.

Sources

- Harris, Cyril M. (2005). Dictionary of Architecture and Construction. McGraw Hill Professional. ISBN 978-0-07-158901-7.

- Horton, Caroline W. (1874). Architecture for General Students. New York: Hurd and Houghton.

- Isambert, Emile (1873). Grèce et Turquie d'Europe. Paris: Librairie Hachette.

- Kleinschmidt, Beda Julius (1912). . In Herbermann, Charles (ed.). Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 15. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- Kovacs, Eduard (7 February 2012). "Fraudsters Install Skimmer on ATM Vestibule Door". Softpedia. Archived from the original on 13 December 2013. Retrieved 13 December 2013.

- McManus, Barbara (February 2007). "Sample Plan of a Roman House". VRoma. The College of New Rochelle. Retrieved 2006-03-02.

- Miles, Margaret M. (2016). A Companion to Greek Architecture. Wiley. ISBN 978-1-118-32760-9.

- Mollett, John William (1883). An Illustrated Dictionary of Words Used in Art and Archaeology. Sampson Low, Marston, Searle, and Rivington.

- Tarbell, Frank Bigelow (1896). A History of Greek Art: With an Introductory Chapter on Art in Egypt and Mesopotamia. Macmillan. ISBN 978-1-4047-8979-1.

Further reading

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 27 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

External links

![]() The dictionary definition of vestibule at Wiktionary

The dictionary definition of vestibule at Wiktionary

![]() Media related to Vestibules at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Vestibules at Wikimedia Commons