Sangiovese

Sangiovese (/ˌsændʒoʊˈveɪzi/, also UK: /-dʒioʊˈ-, -dʒiəˈ-/,[1][2] US: /ˌsɑːn-, ˌsɑːndʒoʊˈviːz, -ˈviːs/,[3][4] Italian: [sandʒoˈveːze]) is a red Italian wine grape variety that derives its name from the Latin sanguis Jovis, "the blood of Jupiter".[5] Though it is the grape of most of central Italy from Romagna down to Lazio (the most widespread grape in Tuscany),[6] Campania and Sicily, outside Italy it is most famous as the only component of Brunello di Montalcino and Rosso di Montalcino and the main component of the blends Chianti, Carmignano, Vino Nobile di Montepulciano and Morellino di Scansano, although it can also be used to make varietal wines such as Sangiovese di Romagna and the modern "Super Tuscan" wines like Tignanello.[7]

| Sangiovese | |

|---|---|

| Grape (Vitis) | |

Sangiovese grapes | |

| Color of berry skin | Purple |

| Species | Vitis vinifera |

| Also called | Brunello, Sangiovese Grosso (more) |

| Origin | Italy |

| Notable regions | Tuscany |

| Hazards | Rot-prone |

| VIVC number | 10680 |

Sangiovese was already well known by the 16th century. Recent DNA profiling by José Vouillamoz of the Istituto Agrario di San Michele all’Adige suggests that Sangiovese's ancestors are Ciliegiolo and Calabrese Montenuovo. The former is well known as an ancient variety in Tuscany, the latter is an almost-extinct relic from Calabria, the toe of Italy.[8] At least fourteen Sangiovese clones exist, of which Brunello is one of the best regarded. An attempt to classify the clones into Sangiovese grosso (including Brunello) and Sangiovese piccolo families has gained little evidential support.[9]

Young Sangiovese has fresh fruity flavours of strawberry and a little spiciness, but it readily takes on oaky, even tarry, flavours when aged in barrels.[10] While not as aromatic as other red wine varieties such as Pinot noir, Cabernet Sauvignon, and Syrah, Sangiovese often has a flavour profile of sour red cherries with earthy aromas and tea leaf notes. Wines made from Sangiovese usually have medium-plus tannins and high acidity.[11]

History

Early theories on the origin of Sangiovese dated the grape to the time of Roman winemaking.[7] It was even postulated that the grape was first cultivated in Tuscany by the Etruscans from wild Vitis vinifera vines. The literal translation of the grape's name, the "blood of Jove", refers to the Roman god Jupiter. According to legend, the name was coined by monks from the commune of Santarcangelo di Romagna in what became the province of Rimini in the Emilia-Romagna region of east-central Italy.[10]

The first documented mention of Sangiovese was in the 1590 writings of Giovanvettorio Soderini (also known under the pen name of Ciriegiulo). Identifying the grape as "Sangiogheto" Soderini notes that in Tuscany the grape makes very good wine but if the winemaker is not careful, it risks turning into vinegar. While there is no conclusive proof that Sangiogheto is Sangiovese, most wine historians generally consider this to be the first historical mention of the grape. Regardless, it would not be until the 18th century that Sangiovese would gain widespread attention throughout Tuscany, being with Malvasia and Trebbiano the most widely planted grapes in the region.[7]

In 1738, Cosimo Trinci described wines made from Sangiovese as excellent when blended with other varieties but hard and acidic when made as a wine by itself. In 1883, the Italian writer Giovanni Cosimo Villifranchi echoed a similar description about the quality of Sangiovese being dependent on the grapes with which it was blended. The winemaker and politician, Bettino Ricasoli formulated one of the early recipes for Chianti when he blended his Sangiovese with a sizable amount of Canaiolo. In the wines of Chianti, Brunello di Montalcino and Vino Nobile di Montepulciano, Sangiovese would experience a period of popularity in the late 19th and early 20th century. In the 1970s, Tuscan winemakers began a period of innovation by introducing modern oak treatments and blending the grape with non-Italian varietals such as Cabernet Sauvignon in the creation of wines that were given the collective marketing sobriquet "Super Tuscans".[7]

Parentage

In 2004, DNA profiling done by researchers at San Michele All'Adige revealed the grape to be the product of a crossing between Ciliegiolo and Calabrese Montenuovo. While Ciliegiolo has a long history tied to the Tuscan region, Calabrese Montenuovo (which is not related to the grape commonly known as Calabrese, or Nero d'Avola) has its origins in southern Italy, where it probably originated in the Calabria region before moving its way up to Campania. This essentially means that the genetic heritage of Sangiovese is half Tuscan and half southern Italian.[10]

Where the crossing between Ciliegiolo and Calabrese Montenuovo occurred is not known, with some believing the cross happened in Tuscany while other ampelographers suggesting it may have happened in southern Italy. Evidence for this latter theory is the proliferation of seedless mutations of Sangiovese, known under various synonyms, throughout various regions of southern Italy including Campania, Corinto nero which is grown on the island of Lipari just north of Sicily and Tuccanese from the Apulia region in the heel of the Italian boot. In Campania, among the many seedless mutations of Sangiovese still growing in the region are Nerello from the commune of Savelli, Nerello Campotu from the commune of Motta San Giovanni, Puttanella from Mandatoriccio and Vigna del Conte.[10]

Relationship with Ciliegiolo

While the parentage of Ciliegiolo and Calabrese Montenuovo for Sangiovese was established based on 50 genetic markers and is generally accepted by ampelographers, some wine texts publish contradictory information that Ciliegiolo is an offspring (rather than parent) of Sangiovese. This belief is based on a 2007 study of 38 genetic markers stating that suggested that Ciliegiolo was the product of Sangiovese crossing with an obscure Portuguese wine grape, Muscat Rouge de Madère, that was once grown on the island of Madeira as well as the Douro and Lisboa wine regions of Portugal. In addition to support of fewer genetic markers, this alternative theory is disputed by geneticists such as José Vouillamoz and Masters of Wine like Jancis Robinson because Muscat Rouge de Madère has no history of ever being cultivated in Italy (where it could have crossed with Sangiovese). Furthermore, while many grapes with lineage involving members of the Muscat family of grapes tend to have pronounced "grapey" flavours characteristic of Muscat grapes, Ciliegiolo exhibits none of those flavour profiles which makes it unlikely to be an offspring of Muscat Rouge de Madère.[10]

Clones and offspring

Early ampelographical research into Sangiovese begun in 1906 with the work of Girolamo Molon. Molon discovered that the Italian grape known as "Sangiovese" was actually several "varieties" of clones which he broadly classified as Sangiovese Grosso and Sangiovese Piccolo. The Sangiovese Grosso family included the clones growing in the Brunello region as well as the clones known as Prugnolo Gentile and Sangiovese di Lamole that was grown in the Greve in Chianti region. The Sangiovese Grosso, according to Molon, produced the highest quality wine, while the varieties in the Sangiovese Piccolo family, which included the majority of clones, produced wine of a lesser degree of quality.[7] In the late 20th century, research by the Italian government and Chianti Classico Consorizo discovered that some of the best producing clones, from a wine quality perspective, came from the Emilia-Romagna region where they are today being propagated under the names R24 and T19.[10]

Another Italian study published in 2008 using DNA typing showed a close genetic relationship between Sangiovese on the one hand and ten other Italian grape varieties on the other hand: Foglia Tonda, Frappato, Gaglioppo, Mantonicone, Morellino del Casentino, Morellino del Valdarno, Nerello Mascalese, Tuccanese di Turi, Susumaniello, and Vernaccia Nera del Valdarno. It is possible, and even likely, that Sangiovese is one of the parents of each of these grape varieties.[12] Since these grape varieties are spread over different parts of Italy (Apulia, Calabria, Sicily and Tuscany), this confirmed by genetic methods that Sangiovese is a key variety in the pedigree of red Italian grape varieties.[10]

DNA analysis in 2001 also suggests a strong genetic relationship between Sangiovese and Aleatico, a grape variety predominantly growing in Apulia, though the exact nature of this relationship has yet to be determined.[10]

Viticulture

Sangiovese has shown itself to be adaptable to many different types of vineyard soils but seems to thrive in soils with a high concentration of limestone, having the potential to produce elegant wines with forceful aromas. In the Chianti Classico region, Sangiovese thrives on the highly friable shale-clay soil known as galestro. In the Montalcino region, there is a high proportion of limestone-based alberese soils alternating with deposits of galestro. The lesser zones of the generic Chianti appellation are predominantly clay, which often produce as high quality of wine as alberese and galestro do.[7]

The grape requires a long growing season, as it buds early and is slow to ripen. The grape requires sufficient warmth to ripen fully, but too much warmth and its flavours can become diluted.[13] Harvests in Italy have traditionally begun after September 29, with modern harvest often taking place in mid-late October. A longer growing season gives the grapes time to develop richness and potential body. However, in cool vintages this can result in the grapes having high levels of acidity and harsh, unripened tannins. In regions (like some areas of Tuscany) that are prone to rainfall in October, there is a risk for rot due to the Sangiovese grape's thin skin.[7] In other areas, such as the dry conditions of the Columbia Valley AVA of Washington State, the grape has good resistance to drought conditions and often requires little irrigation.[10]

For the best quality, yields need to be kept in check as the vine is notably vigorous and prone to overproduction. In Chianti, most quality conscious producers limit their yields to 3 pounds (1.5 kg) of fruit per vine. Wine made from high-yielding vines tend to produce wines with light color, high acidity, and less alcohol, which are likely to oxidize ("brown") prematurely due to a lower concentration of tannins and anthocyanins (anti-oxidants).[13] Fully developed grapes are typically 19 mm long x 17 mm wide, with an average weight of 3 grams.[14]

Soils with low fertility are ideal and help control some of the vigor of the vine. Planting vines in high densities in order to curb vigor may have the adverse effect of increasing foliage and limiting the amount of direct sunlight that can reach the ripening grapes.[13] Advances in understanding the quality and characteristics of the different clones of Sangiovese has led to the identification and propagation of superior clones. While high-yielding clones have been favored in the past, more attention is being paid to matching the clone to the vineyard site and controlling the vine's vigor.[7]

Winemaking

The high acidity and light body characteristics of the Sangiovese grape can present a problem for winemaking. The grape also lacks some of the color-creating phenolic compounds known as acylated anthocyanins.[13] Modern winemakers have devised many techniques trying to find ways to add body and texture to Sangiovese — ranging from using grapes that come from extremely low yielding vines, to adjusting the temperature and length of fermentation and employing extensive oak treatment. One historical technique is the blending of other grape varieties with Sangiovese, in order to complement its attractive qualities and fill in the gaps of some of its weaker points. The Sangiovese-based wines of Chianti have a long tradition of liberally employed blending partners—such as Canaiolo, Ciliegiolo, Mammolo, Colorino and even the white wine grapes like Trebbiano and Malvasia. Since the late 20th century, Bordeaux grapes, most notably Cabernet Sauvignon, have been a favored blending partner though in many Italian DOC/DOCG regions there is often a maximum limit on the amount of other varietals that can be blended with Sangiovese; in Chianti the limit for Cabernet is 15%.[7]

Other techniques used to improve the quality of Sangiovese include extending the maceration period from 7–12 days to 3–4 weeks to give the must more time to leach vital phenols out of the grape skins. Transferring the wine during fermentation into new oak barrels for malolactic fermentation gives greater polymerization of the tannins and contributes to a softer, rounder mouthfeel. Additionally, Sangiovese has shown itself to be a "sponge" for soaking up sweet vanilla and other oak compounds from the barrel. For aging the wine, some modern producers will utilize new French oak barrels but there is a tradition of using large, used oak botti barrels that hold five to six hectoliters of wine. Some traditional producers still use the old chestnut barrels in their cellars.[13]

Wine regions

While Sangiovese plantings are found worldwide, the grape's homeland is central Italy. From there the grape was taken to North and South America by Italian immigrants. It first achieved some popularity in Argentina where in the Mendoza region it produced wines that had few similarities to its Tuscan counterparts. In California the grape found a sudden surge of popularity in the late 1980s with the "Cal-Ital" movement of winemakers seeking red wine alternatives to the standard French varietals of Cabernet Sauvignon, Merlot and Pinot noir.[7]

While there was over 100,000 hectares (250,000 acres) of Sangiovese planted in Italy in 1990, plantings of the grape began to decline. However, at the turn of the 21st century, Italy was still the leading source for Sangiovese, with 69,790 hectares (172,500 acres) planted in 2000, primarily in the Tuscany, Emilia-Romagna, Sicily, Abruzzo and Marche regions.[10] Argentina was next with 6,928 acres (2,804 ha), followed by Romania with 1,700 hectares (4,200 acres), the Corsica region in France with 1,663 hectares (4,110 acres), California with 1,371 hectares (3,390 acres) and Australia with 440 hectares (1,100 acres).[13]

Italy

In Italy, Sangiovese is the most widely planted red grape variety. It is an officially recommended variety in 53 provinces and an authorized planting in an additional 13.[13] It accounts for approximately 10% of all vineyard plantings in Italy[15] with more than 100,000 hectares (250,000 acres) planted to one of the many clonal variation of the grape. Throughout Italy it is known under a variety of names including Brunello, Morellino, Nielluccio and Prugnolo Gentile. It is the main grape used in the popular red wines of Tuscany, where it is the solitary grape of Brunello di Montalcino and the primary component of the wines of Chianti, Vino Nobile di Montepulciano and many "Super Tuscans". Outside Tuscany, it is found throughout central Italy where it places an important role in the Denominazione di Origine Controllata e Garantita (DOCG) wines of Torgiano Rosso Riserva in Umbria, Conero in Marche and the Denominazione di Origine Controllata (DOC) wines of Montefalco Rosso in Umbria and Rosso Piceno in Marche. Significant Sangiovese plantings can also be found outside central Italy in Lombardia, Emilia-Romagna, Valpolicella and as far south as Campania and Sicily.[7]

The intense fruit and deep color of Cabernet was shown to be well suited for blending with Sangiovese but banned in many Italian DOCs. In the 1970s, the rise of "Super Tuscans"-wines that eschew DOC regulation in favor of the lower classification of vino da tavola-increased the demand for more flexibility in the DOC laws. While the first DOC to be permitted to blend Cabernet Sauvignon with Sangiovese was approved for Carmignano in 1975, most of Tuscany's premier wine regions were not permitted to blend Cabernet Sauvignon with Sangiovese till the late 20th century.[7]

Tuscany

From the early to mid-20th century, the quality of Chianti was in low regard. DOC regulation that stipulate the relatively bland Trebbiano and Malvasia grapes needed to account for at least 10% of the finished blend, with consequent higher acidity and diluted flavours. Some wineries trucked in full bodied and jammy red wines from Sicily and Apulia to add color and alcohol to the blend—an illegal practice that did little to improve the quality of Chianti. From the 1970s through the 1980s, a revolution of sorts spread through Tuscany as the quality of the Sangiovese grape was rediscovered. Winemakers became more ambitious and willing to step outside DOC regulations to make 100% varietal Sangiovese or a "Super Tuscan" blend with Bordeaux varietals like Cabernet and Merlot.[13]

Today there is a broad range of style of Chianti reflecting the Sangiovese influence and winemaker's touch. Traditional Sangiovese emphasize herbal and bitter cherry notes, while more modern, Bordeaux-influenced wines have more plum and mulberry fruit with vanilla oak and spice. Stylistic and terroir based differences also emerge among the various sub-zones of the Chianti region. The ideal vineyard locations are found on south and southwest-facing slopes at altitudes between 490–1,800 ft (150–550 m). In general, Sangiovese has a more difficult time fully ripening in the Chianti region than it does in the Montalcino and Maremma regions to the south. This is due to cooler nighttime temperatures and high propensity for rainfall in September and October that can affect harvest time.[13]

In the mid-19th century, a local farmer named Clemente Santi isolated certain plantings of Sangiovese vines in order to produce a 100% varietal wine that could be aged for a considerable period of time.[16] In 1888, his grandson Ferruccio Biondi-Santi—a veteran soldier who fought under Giuseppe Garibaldi during the Risorgimento—released the first "modern version" of Brunello di Montalcino, which was aged for over a decade in large wood barrels. By the mid-20th century, this 100% varietal Sangiovese was eagerly being sought out by critics and wine drinkers alike.[17] The Montalcino region seems to have ideal conditions for ripening Sangiovese with the potential for full ripeness achievable even on north-facing slopes. These slopes tend to produce lighter and more elegant wines that then those made from vineyards on south and southwest facing slopes.[13]

In the late 20th and early 21st century, the Maremma region located in the southwest corner of Tuscany has seen vast expansion and a surge of investment from outside the region. The area is reliably warm with a shorter growing season. Sangiovese grown in the Maremma is capable of developing broad character but does have the potential of developing too much alcohol and not enough aroma compounds.[13]

Outside Tuscany

Sangiovese is considered the "workhorse" grape of central Italy, producing everything from everyday drinking to premium wines in a variety of styles-from red still wines, to rosato to sweet passito, semi-sparkling frizzante and the dessert wine Vin Santo. In northern Italy, the grape is a minor variety with it having difficulties ripening north of Emilia-Romagna. In the south, it is mainly used as a blending partner with the region's local grapes such as Primitivo, Montepulciano and Nero d'Avola.[13]

In the Romagna region of Emilia-Romagna, the same grape is called Sangiovese di Romagna and is widely planted in all the Romagna region east of Bologna. Like its neighboring Tuscan brother, Sangiovese di Romagna has shown itself to spring off a variety of clones that can produce a wide range of quality—from very poor to very fine. Viticulturists have worked with Romagna vines to produce new clonal varieties of high quality (most notably the clones R24 & T19).

Sangiovese di Romagna adapts to different soil types, producing richer, more full bodied and tannic wines in the central provinces of Forlì and Ravenna and lighter, fruitier wines in the western and eastern extremes of the regions near the border with Bologna and Marche. The grape seems to produce the highest quality wine in the sandstone and clay rich hills south of the Via Emilia near the Apennines which is covered by much of the Sangiovese di Romagna DOC zone. The higher summer time temperatures of this area gives more opportunity for Sangiovese to sufficiently ripen.[7] The Sangiovese di Romagna DOC zone includes over 17,500 acres (7,100 ha) of Sangiovese that produces on average 3.4 million U.S. gallons (130,000 hl) of wine a year.[7]

Other Old World wine regions

In France, while some producers in the Languedoc are now experimenting with the variety, Sangiovese has a long history on the island of Corsica where it is known as Nielluccio. The grape was likely brought to the island sometime between 14th and 18th century when it was ruled by the Republic of Genoa. Here it is often blended with Sciaccarello and is a permitted grape in several Appellation d'Origine Contrôlée (AOC)s, most notable in Patrimonio, where it is used for both red and rosé wine production. In 2008, there were 1,319 hectares (3,260 acres) of Sangiovese/Nielluccio on Corsica.[10]

In Greece, producers in the northeastern wine region of Drama in East Macedonia and Thrace are experimenting with oak-aged "Super Tuscan" style blends of Sangiovese and Cabernet Sauvignon. Additional plantings of Sangiovese can be found in Israel, Malta, Turkey and Switzerland.[10]

United States and Canada

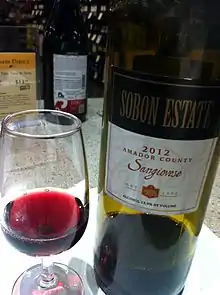

Italian immigrants brought Sangiovese to California in the late 19th century,[9] possibly at the Seghesio Family's "Chianti Station," near Geyserville. But it was never considered very important until the success of the Super Tuscans in the 1980s spurred new interest in the grape. In 1991, there were nearly 200 acres (81 ha) planted with Sangiovese. By 2003, that number rose to nearly 3,000 acres (1,200 ha) with plantings across the state, most notably in Napa Valley, Sonoma county, San Luis Obispo, Santa Barbara and the Sierra Foothills.[7] However, in recent years plantings of the variety have declined to 1,950 acres (790 ha) by 2010.[10]

Early results in the late 20th century, were not very promising for California winemakers. Poor site and clonal selection had the grape planted in vineyards that gave it too much exposure to the sun, producing wines that had little in common with the wines of Tuscany. The Antinori family, which once owned Atlas Peak Vineyards located in the Atlas Peak AVA in the foothills of Napa Valley found that the greater intensity of sunlight in California may have been one possible factor for the poorer quality.[13] Today the style of these Californian Sangiovese tend to be more fruit-driven than their Tuscan counterparts with some floral notes. Recent years have focused on improving vineyard site and clonal selection as well as giving the vines time to age and develop in quality.[7]

In Washington State, one of the first commercial plantings of Sangiovese was at Red Willow Vineyard in the Yakima Valley AVA. Today, winemakers are seeking out locations that can highlight the varietal character of Sangiovese. These young plantings in areas such as Walla Walla, Naches Heights AVA and Yakima Valley have so far produced wines with a spicy and tart cherry flavours, anise, red currants, and tobacco leaf notes.[18] Like in California, plantings of Sangiovese in Washington have declined in recent years to 185 acres (75 ha) in 2011.[10]

Other areas in the United States with sizable plantings of Sangiovese include the Rogue Valley and Umpqua AVA in Oregon, the Monticello in Virginia, the Sonoita AVA with 45 acres planted in Arizona, and Texas Hill Country in Texas.[19][20]

In Canada, there are less than 10 acres (4.0 ha) of Sangiovese planted, mostly in Ontario where some producers in Niagara-on-the-Lake are experimenting with ice wine versions of the grape. A small amount of the grape can also be found in British Columbia.[10]

Other New World regions

Italian immigrants introduced the Sangiovese vine to Argentina in the late 19th and early 20th century. Early site and clonal selection was less than ideal and, like California and Australia, recent endeavors have focused on finding the best clones to use and the right vineyard locations. The grape is not widely planted in Argentina and the focus is mostly on the export market. In 2008 there were 2,319 hectares (5,730 acres) of Sangiovese planted, most of it in the Mendoza wine region with other isolated plantings in La Rioja and San Juan.[10]

Across the Andes range, Chilean winemakers have been experimenting with plantings with 124 hectares (310 acres) in 2008. Brazil reported 25 hectares (62 acres) of Sangiovese in 2007.[10] The growing Mexican wine industry has also recently begun planting the vine.[13]

Sangiovese is becoming increasingly popular as a red wine grape in Australia, having been introduced by the CSIRO in the late 1960s.[21] For many years, this single clone (H6V9) imported from the University of California-Davis was the only available clone for Australian winemakers. The first large-scale commercial planting of the grape was in the 1980s when Penfolds expanded their Kalimna vineyard in the Barossa Valley. As the availability of clones expanded (currently 10 available commercially as of 2011), so did plantings of Sangiovese with 517 hectares (1,280 acres) in 2008.[10]

As in California, Australian winemakers have begun seeking out the best vineyard location for the grape and being more selective in which clones are planted. Some regions that have shown promise for the grape include the Karridale and Margaret River areas of Western Australia; Langhorne Creek , Strathalbyn and Port Lincoln in South Australia; Canberra and Young in New South Wales; Stanthorpe in Queensland and the western edge of the Great Dividing Range in Victoria.[13]

In New Zealand, the first varietal version of Sangiovese was released in 1998 and today there are 6 hectares (15 acres) of the grape planted, mostly on the North Island around Auckland.

A small amount of Sangiovese is grown in South Africa with 63 hectares (160 acres) reported in 2008, mostly in the Stellenbosch and Darling regions.[10] About 10 wineries make Sangiovese[22]

Wines

Wines made from Sangiovese tend to exhibit the grape's naturally high acidity as well as moderate to high tannin content and light color. Blending can have a pronounced effect on enhancing or tempering the wine's quality. The dominant nature of Cabernet can sometimes have a disproportionate influence on the wine, even overwhelming Sangiovese character with black cherry, black currant, mulberry and plum fruit. Even percentages as low as 4 to 5% of Cabernet Sauvignon can overwhelm the Sangiovese if the fruit quality is not high. As the wine ages, some of these Cabernet dominant flavours can soften and reveal more Sangiovese character.[23]

Different regions will impart varietal character on the wine with Tuscan Sangiovese having a distinctive bitter-sweet component of cherry, violets and tea. In their youth, Tuscan Sangiovese can have tomato-savoriness to it that enhances its herbal component. Californian examples tend to have more bright, red fruit flavours with some Zinfandel-like spice or darker fruits depending on the proportion of Cabernet blended in. Argentine examples showing a hybrid between the Tuscan and California Sangiovese with juicy red fruit wines that end on a bitter cherry note.[13]

Sangiovese based wines have the potential to age but the vast majority of Sangiovese wines are intended to be consumed relatively early in their lives. The wines with the longest aging potential are the Super Tuscans and Brunello di Montalcino wines that can age for upwards of 20 years in ideal vintages. These premium examples may need 5 to 10 years to develop before they drink well. The potentially lighter Vino Nobile di Montepulciano, Carmignano and Rosso di Montalcino tend to open earlier (around 5 years of age) but have a shorter life span of 8 to 10 years. The aging potential of Chianti is highly variable, depending on the producer, vintage and sub-zone of the Chianti region it is produced in. Basic Chianti is meant to be consumed within 3 to 4 years after vintage while top examples of Chianti Classico Riserva can last for upwards of 15 years. New World Sangiovese has so far, shown a relatively short window of drinkability with most examples best consumed with 3 to 4 years after harvest with some basic examples of Argentine Sangiovese having the potential to only improve for a year after bottling.[13]

With food

Sangiovese's high acidity and moderate alcohol makes it a very food-friendly wine when it comes to food and wine pairings. One of the classic pairings in Italian cuisine is tomato-based pasta and pizza sauces with a Sangiovese-based Chianti. Varietal Sangiovese or those with a smaller proportion of the powerful, full-bodied Cabernet blended in, can accentuate the flavours of relatively bland dishes like meatloaf and roast chicken. Herb seasoning such as basil, thyme and sage play off the herbal notes of the grapes. Sangiovese that has been subject to more aggressive oak treatment pairs well with grilled and smoked food. If Cabernet, Merlot or Syrah plays a dominant role, the food pairing option should treat the Sangiovese blend as one of those fuller-bodied reds and pair with heavier dishes such as steak and thick soups like ribollita and puréed bean soup.[23]

Synonyms

Over the years, Sangiovese has been known under a variety of synonyms, many of which have come to be associated with a particular clone of the grape variety. Among the synonyms recognized for the grape are: Brunelletto (in the Grosseto region of Tuscany), Brunello, Brunello di Montalcino, Cacchiano (in Tuscany), Calabrese (in Tuscany), Cardisco, Chiantino (in Tuscany), Cordisio, Corinto nero (on the island of Lipari in Sicily), Dolcetto Precoce, Guarnacciola (in the Benevento region of Campania), Ingannacane, Lambrusco Mendoza (in Tuscany), Maglioppa, Montepulciano, Morellino, Morellone, Negrello (in Calabria), Negretta, Nerello (in Sicily), Nerello Campotu (in Calabria), Nerino, Niella (in Corsica), Nielluccia, Nielluccio (in Corsica), Pigniuolo Rosso, Pignolo, Plant Romain, Primaticcio, Prugnolo, Prugnolo Dolce (in Tuscany), Prugnolo di Montepulciano, Prugnolo Gentile, Prugnolo Gentile di Montepulciano, Puttanella (in Calabria), Riminese, Rosso di Montalcino, San Gioveto, San Zoveto (in Tuscany), Sancivetro, Sangineto, Sangiogheto (in Tuscany), Sangiovese dal Cannello Lungo, Sangiovese di Lamole, Sangiovese di Romagna, Sangiovese Dolce, Sangiovese Gentile, Sangiovese Grosso, Sangiovese Nostrano, Sangiovese Piccolo, Sangiovese Toscano, Sangioveto (in Tuscany), Sangioveto dell'Elba, Sangioveto Dolce, Sangioveto Grosso, Sangioveto Montanino, Sanvincetro, Sanzoveto, Tabernello, Tignolo, Tipsa, Toustain (in Algeria), Tuccanese (in Apulia), Uva Abruzzi, Uva Tosca, Uvetta, Uva brunella, Uva Canina, Vigna del Conte (in Calabria) and Vigna Maggio (in Tuscany).[10][14][21]

References

- "Sangiovese". Collins English Dictionary. HarperCollins. Retrieved May 29, 2019.

- "Sangiovese" (US) and "Sangiovese". Lexico UK English Dictionary. Oxford University Press. Archived from the original on 2020-03-22.

- "Sangiovese". The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language (5th ed.). HarperCollins. Retrieved May 29, 2019.

- "Sangiovese". Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary. Retrieved May 29, 2019.

- Robinson, J (1986). Vines, Grapes & Wines. Mitchell Beazley. pp. 150–152. ISBN 1-85732-999-6.

- it:Sangiovese

- Robinson, J, ed. (2006). The Oxford Companion to Wine (3 ed.). Oxford University Press. pp. 606–607. ISBN 0-19-860990-6.

- Robinson, J. "Italian grape mysteries unraveled". jancisrobinson.com. Archived from the original on 2011-07-13. Retrieved 2007-04-03.

- "Sangiovese". Wine Pros.

- J. Robinson, J. Harding and J. Vouillamoz, Wine Grapes - A complete guide to 1,368 vine varieties, including their origins and flavours, pp. 942-946, Allen Lane 2012 ISBN 978-1-846-14446-2

- Wine & Spirits Education Trust, Wine and Spirits: Understanding Wine Quality, pp. 6-9, Second Revised Edition (2012), London, ISBN 9781905819157

- ‘Sangiovese’ and ‘Garganega’ are two key varieties of the Italian grapevine assortment evolution Archived 2011-07-19 at the Wayback Machine, M. Crespan, A. Calò, S. Giannetto, A. Sparacio, P. Storchi and A. Costacurta, Vitis 47 (2), pp. 97–104 (2008).

- Oz Clarke, Encyclopedia of Grapes, pp. 209-216, Harcourt Books 2001 ISBN 0-15-100714-4.

- Maul, E.; Eibach, R. (1999). "Vitis International Variety Catalogue". Information and Coordination Centre for Biological Diversity (IBV) of the Federal Agency for Agriculture and Food (BLE), Deichmanns Aue 29, 53179 Bonn, Germany. Archived from the original on 2007-04-27. Retrieved 2007-06-16.

- "Italian Wine Journeys:Chianti". IntoWine.com. 26 March 2007. Retrieved 2009-11-06.

- M. Ewing-Mulligan & E. McCarthy, Italian Wines for Dummies, p. 159-161 Hungry Minds 2001 ISBN 0-7645-5355-0.

- H. Johnson, Vintage: The Story of Wine, pp. 423, Simon and Schuster 1989 ISBN 0-671-68702-6.

- P. Gregutt, Washington Wines and Wineries: The Essential Guide, p. 74, University of California Press 2007 ISBN 0-520-24869-4.

- Appellation America "Sangiovese" Accessed: January 4, 2009.

- "ARIZONA VINEYARD SURVEY - 2013" (PDF).

- State Library of South Australia Archived 2007-08-07 at the Wayback Machine

- van Zyl, P, ed. (2009). Platter's South African Wines 2009. Newsome McDowall. p. 26. ISBN 978-0-9584506-7-6.

- E. Goldstein, Perfect Pairings, pp. 176-180, University of California Press 2006 ISBN 978-0-520-24377-4.