Psychic archaeology

Psychic archaeology is a loose collection of practices involving the application of paranormal phenomena to problems in archaeology. It is not considered part of mainstream archaeology, or taught in academic institutions. It is difficult to test scientifically, since archaeological sites are relatively abundant, and all of its verified predictions could have been made via educated guesses.[1][2]

| Part of a series on the |

| Paranormal |

|---|

Practitioners of psychic archaeology utilize a variety of methods of divination ranging from pseudoscientific methods such as dowsing and channeling.[3] Some psychic archaeologists engage in fieldwork while others, such as Edgar Cayce (who claims to have had access to ancient Akashic records), exclusively engage in remote viewing. Frederick Bligh Bond's research at Glastonbury Abbey is one of the first documented examples of psychic archaeology and remains a principal case in many discussions of psychic archaeology.[4]

Description

Psychic archaeology is the use of extrasensory perception to locate sites for archaeological digs, or describe context of artifacts. Psychic archaeology is alluring for several reasons, respective to the type of psychic archaeology employed. For instance, surveying techniques such as dowsing are less costly in terms of time and equipment than conventional noninvasive surveying techniques such as Ground Penetrating Radar or magnetometery surveys. Techniques for locating sites and test pits such as automatic writing and various scrying techniques are easy to perform. Psychic archaeologists claim that many of their techniques address lives of the past directly. Whereas accepted archaeologists make inferences about lives of the past based on material culture, some psychic archaeologists say they have visions of non-material aspects of the lives they study.

Methods

There are several common methods employed by practitioners of psychic archaeologists including:

Dowsing

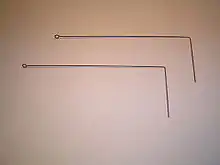

Dowsing in psychic archaeology can take on many forms. One of the better publicized methods and the subject of psychic archaeologist Karen Hunt's 1981 masters thesis at Indiana University involves dowsing for Electromagnetic Photo-Fields (EMPF) using two L-shaped [Ferrous] coat hangers bent about 17.8 cm from the end as electromagnetic photo sensors. Hunt stated that the electromagnetic photo sensors detect EMPF similar to a proton magnetometer detecting magnetic fields. Crossed dowsing rods indicated the crossing of an EMPF, which are said to be three-dimensional patterns generated by man-made objects left in place for at least six-months.[5] There are other methods of dowsing employed in psychic archaeology with less inherent scientism than EMPF. Often conventional dowsers will offer their services to archaeologist with varying explanation for their methods.[6] Straddling the border of dowsing and channeling is a technique known as map dowsing, in which a medium or psychic dangles a pendulum over a map of the area of a potential dig to divine ideal locations for test pits or excavation.

Psychometry

An example of psychometry in psychic archaeology occurred at 17:45, 22 October 1941 when Professor Stanisław Poniatowski of the University of Warsaw handed Polish psychic Stefan Ossowiecki a projectile point from the Magdalenian culture. After holding the artifact Ossowiecki stated that it was a spear point from France or Belgium, belonging to round house dwelling people with brownish skin, black hair, short stature, large hands, feet and hips wearing skins. He describes a funeral pyre, burial, and two domesticated dogs.[7] Jeffrey Goodman, author and psychic archaeologist, considers Ossowiecki's psychometry validated for the following reasons: large hipped women are observed in Magdalenian Venus figurines, bone needles associated with Magdalenian culture may have been used to sew skin clothing, and the bearded man on the funeral pyre “may have been one of the bearded Magdalenians who are found represented in Magdalenian cave art.”[7]

Sites

Chichén Itzá

Augustus Le Plongeon, an eccentric explorer who concentrated on Maya sites in the northern Yucatan Peninsula, was an early practitioner of psychic archaeology. In 1877, Juan Péon Contreras, director of the Museo Yucateco in Mérida, noted that Le Plongeon's discoveries of sculpture at Chichén Itzá resulted from the application of "abstruse archaeological reasoning and... meditation.".[8] R. Tripp Evans refers to this as "psychic archaeology," noting that Le Plongeon's wife Alice Dixon Le Plongeon had an avid interest in mesmerism, séance, and the occult.[8] Helena Blavatsky, a co-founder of the Theosophical Society, regarded the work of the Le Plongeons as proving the validity of "metaphysical archaeology.".[9] However, professional archaeologists regard Le Plongeon as an obvious crank.[8][10]

Glastonbury Abbey

Glastonbury Abbey was a Catholic religious complex located at Glastonbury, UK, until 1539, when it was destroyed by edict of King Henry VIII. According to Frederick Bligh Bond the abbey was founded in 166 CE, although this founding date is disputed by historians; the commonly accepted date is in the 7th century when, according to the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle King Ine of Wessex established a minster at Glastonbury.[11] On November 17, 1907, F. Bligh Bond had his friend Captain John Bartlett (Given the pseudonym John Alleyne in The Gate of Remembrance ) engage in communicating with spirits via automatic writing for the purpose of learning about Glastonbury Abbey's past. Captain Bartlett's communication with spirits produced two sketches of the abbey's layout signed by "Gulielmus Monachus." The layouts showed a chapel to the east of the abbey that was unknown to F. Bligh Bond, he asked that Captain Bartlett's source provide more information about this building. Accordingly, Captain Bartlett wrote that the chapel had been erected by Abbot Beere, completed by Abbot Whiting and named in honor of King Edgar.

F. Bligh Bond began excavation at Glastonbury in the summer of 1909. While excavating he demonstrated the accuracy of Captain Bartlett's sketches discovering Edgar Chapel in the location indicated by Captain Bartlett.[7]

Bond didn't reveal that he was using psychic powers until 1917, when he had already presented his results. The Church of England officials were so embarrassed that they fired him.[12]

Mainstream archeologists are far from nonplussed about the discovery, reminding people that F. Bligh Bond was an expert in medieval church architecture, that most of the site had already been dug out, and that the location of the chapel could be easily guessed from the existing data.[4][12] Archaeologist Stephen Williams said that "Culture is a patterned behavior, and medieval cathedrals are some of the most patterned pieces of construction in our culture... All he had to do was turn to almost any nearby structure, such as Salisbury Cathedral, less than fifty miles to the east, and see its Trinity Chapel behind the main altar and guess that Glastonbury would have one too.[4]

Point Cook

Point Cook, Australia (37°55′33.6″S 144°47′30.7″E), was the location of a psychic archaeological survey by Karen A. B. Hunt M.A. in 1981. Hunt employed dowsing rods to detect Electromagnetic Photo-Fields (EMPF). Hunt mapped the locations of 129 buildings or cultural points including the house, outbuildings, a windmill, a tank stand, the fences and gates of the homestead. While the location of the windmill and tank stand match established facts, skeptic Mark Plummer considers Hunt's survey dubious for several reasons, including architectural style, which he and a team of architects find more indicative of 1870–1900 American architecture than Australian Colonial architecture.[4][5] In 1985, Hunt declined to participate in a proposed scientifically controlled test of EMPF.[13]

Validity

Advocates of psychic archaeology believe that at best it possesses the power to answer questions about the lives in the past not answerable using the archaeological record, and also to locating prime archaeological sites.[7] They believe that, at worst, psychic archaeologists can locate and excavate important sites that may not be excavated without the motivation of psychic guidance.[14] Skeptics, on the other hand, usually question the existence of psychic abilities, ascribing the occasional apparent successes of psychic archaeology to fallacious thinking on the part of practitioners and cite phenomena such as coincidence, confirmation bias, cherry picking or outright trickery.[16] Skeptics compare psychic archaeologists to psychic detectives.

It is difficult to test psychic archaeology empirically, since archaeological discoveries are relatively abundant; anyone can predict the location of a site, using only a bit of archaeological knowledge and common sense.[1] The same applies for finding objects inside an already identified site.[1] Also, some sites, like the Alexandria harbor, are so rich in objects that one can dig in any random place and find at least one object.[1] Predictions about the lifestyle of ancient civilizations can't be verified due to the lack of written records.[1]

Names in psychic archaeology

- Hella Hammid[17]

- Augustus Le Plongeon

- Frederick Bligh Bond[15]

- George S. McMullen[18]

- Stefan Ossowiecki[7]

- Edgar Cayce[4]

- Karen Hunt [5] (Winner 1984 Bent Spoon Award)

- J. Norman Emerson [4] of the University of Toronto

- Stephan A. Schwartz[15]

- Jeffrey Goodman[7]

In fiction

- Sophia Hapgood, a character in the Indiana Jones canon, is both a psychic and an archaeologist. Her name is a reference to Charles Hapgood, a proponent of pseudoscientific pole shift theory.

See also

References

- Kenneth L. Feder (2010), Encyclopedia of Dubious Archaeology: From Atlantis to the Walam Olum (illustrated ed.), ABC-CLIO, pp. 6, 56–57, 103, 203, 221–223, ISBN 978-0-313-37918-5

- Cole, John R. (1978). "Anthropology Beyond the Fringe: Ancient Inscriptions, Early Man and Scientific Method". The Skeptical Inquirer 2(2): 62–71.

- Feder, Kenneth L. (1980). "Psychic Archaeology: The Anatomy of Irrationalist Prehistoric Studies". The Skeptical Inquirer 4(4): 32–43.

- Williams, Stephen (1991). "Psychic Archaeology". Fantastic Archaeology: The Wild Side of North American Prehistory. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 0-8122-1312-2.

- Plummer, Mark (1991). "Locating Invisible Buildings". The Skeptical Inquirer. 15 (4): 386–397.

- Van Leusen, Martijn (1999). "Dowsing and Archaeology". The Skeptical Inquirer. 23 (2): 33–41.

- Goodman, Jeffrey (1977). Psychic Archaeology: Time Machine to the Past. New York: Berkley Publishing. pp. 31–53. ISBN 978-0-425-05000-2.

- Evans, R. Tripp (2004). Romancing the Maya: Mexican Antiquity in the American Imagination 1820–1915. Austin: University of Texas Press. ISBN 978-0-292-72221-7., p. 131

- Desmond, Lawrence; Phyllis, Messenger (1988). A Dream of Maya: Augustus and Alice Le Plongeon in Nineteenth-Century Yucatan. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press., p. 131

- Desmond, Lawrence; Phyllis, Messenger (1988). A Dream of Maya: Augustus and Alice Le Plongeon in Nineteenth-Century Yucatan. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press.

- "History and Archaeology – Glastonbury Abbey". Retrieved 22 October 2010.

- Joe Nickell (2007), Adventures in Paranormal Investigation (illustrated ed.), University Press of Kentucky, pp. 48–49, ISBN 978-0-8131-2467-4

- Feder, Kenneth L. (2002). Frauds, Myths, and Mysteries: Science and Pseudoscience. McGraw-Hill. pp. 256. ISBN 978-0767427227.

- Varvoglis, Mario. "Psychic Archeology". Parapsychological Association. Archived from the original on 2004-06-18. Retrieved 2010-10-20.

- Schwartz, Stephan (1978). The Secret Vault of Time: Psychic Archaeology and the Quest for Man's Beginnings. New York: Grosset & Dunlap. pp. 172–181 and 191–197. ISBN 0-448-12717-2.

- Doeser, James (2008). "Psychic Archaeology". Bad Archaeology. Retrieved 2010-10-28.

- CIA.gov

- Psychic Archeology by Mario Varvoglis Ph.D.

Further reading

- Bailey, Richard, Eric Cambridge and Dennis Biggs. 1988. Dowsing and Church Archaeology. ISBN 978-0-946707-13-3

- Bond, Fredrick. 2010 (Reprint). The Gates of Remembrance. ISBN 978-0-548-00420-3

- Jones, David. 1979. Visions of Time: Experiments In Psychic Archaeology ISBN 0-8356-0525-6

- McKusick, Marshall (1982), "Psychic Archaeology: Theory, Method, and Mythology", Journal of Field Archaeology, 9 (1): 99–118(20), doi:10.1179/009346982791974697

- Schwartz, Stephan. 1983. The Alexandria Project. ISBN 978-0-595-18348-7