Pułtusk

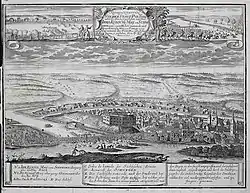

Pułtusk (pronounced Poow-toosk [ˈpuu̯tusk]) is a town in northeast Poland, by the river Narew. Located 70 kilometres (43 miles) north of Warsaw in the Masovian Voivodeship, it has a population of 19,224 as of 2023.[1] Known for its historic architecture and Europe's longest paved marketplace (380 metres (1,250 ft) in length),[2] it is a popular weekend destination for the residents of Warsaw.[2]

Pułtusk | |

|---|---|

Old town, with Europe's longest marketplace | |

Flag  Coat of arms | |

Pułtusk | |

| Coordinates: 52°42′N 21°5′E | |

| Country | |

| Voivodeship | Masovian |

| County | Pułtusk |

| Gmina | Pułtusk |

| Established | 9th–10th century |

| Town rights | 1257 |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Wojciech Gregorczyk |

| Area | |

| • Total | 22.83 km2 (8.81 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 80 m (260 ft) |

| Population (2006) | |

| • Total | 19,229 |

| • Density | 840/km2 (2,200/sq mi) |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+2 (CEST) |

| Postal code | 06-100 |

| Area code | +48 023 |

| Car plates | WPU |

| Website | www |

Pułtusk is one of the oldest townships in Poland, having received city rights from Duke Siemowit I of Masovia in 1257. Throughout the 15th and 17th centuries, the settlement was a significant economic centre of Masovia. The favourable geographical placement of the town on the Narew, along which goods were transported to the port of Gdańsk on the Baltic Sea, contributed to the town's importance. Pułtusk was also the site of notable events, such as the Napoleon's 1806 battle, and the world's largest meteorite shower to date in 1868, among others.

History

Middle Ages

The town has existed since at least the 10th century. In the Middle Ages, the Castle in Pułtusk was one of the most important defensive forts in northern Masovia against the attacks of Old Prussians and Lithuanians. According to a legend, the town initially was known as Tusk; however, after a flood that destroyed half of the city, it was renamed as Pułtusk (Pół- or puł- being a Polish prefix for a half). Most historians believe that it was named after a small river known as Pełta.

From the 11th century onwards, the town belonged to the bishops of Płock. Due to a ford on the river located nearby, Pułtusk became an important centre of trade and commerce. It received its civic charter in 1257, modelled after that of Chełmno (Kulm Law). In 1440 an academy was founded in the town, and it became one of the most influential schools of higher education in the Polish Kingdom. Among its professors were Jakub Wujek and Piotr Skarga. By 1595 there were more than 600 students, and their number reached 900 by 1696.

The town was destroyed by Lithuanians in 1262 and 1324. In the 14th century, Pułtusk became the official seat of Płock bishops. The town was again burnt by Lithuanians in 1368, but following the Union of Krewo between Poland and Lithuania, the Lithuanian raids were stopped, and the town quickly recovered.

By the 15th century Pułtusk's merchants were among the richest in Poland. The town was granted a privileges of organizing nine grand fairs a year and two small markets a week. The city also gained much profit from exporting wood and grain to Gdańsk, as well as from mead and beer production.

In around 1405, the Mayor's House, today known as the "Polonia House" or "Polonia Castle", was constructed. In 1449 a Gothic church was added to the city's facilities. In the 16th century the castle was rebuilt by several renowned Italian architects, including Giovanni Battista of Venice and Bartolommeo Berrecci, and Giovanni Cini of Siena.

Early modern period

Pułtusk was located in the Masovian Voivodeship in the Greater Poland Province of the Polish Crown. In 1530 the first Masovian printing house was opened. In 1566 one of the first public theatres in Poland was established in Pułtusk. In the 16th century the town was visited by many notable individuals, such as King Sigismund III Vasa, and poets Jan Kochanowski and Maciej Kazimierz Sarbiewski.

On 21 April 1703 during the Great Northern War, a decisive battle was fought in Pułtusk, where the Swedish army under Charles XII defeated and captured a large part of the Saxon army under Graf von Steinau. Although the town and the castle were initially conquered by Polish forces, they were later recaptured by the Swedish army, which looted and destroyed it.

After the Partitions of Poland, the town was annexed by the Kingdom of Prussia. The Polish forces of General Antoni Madaliński stationed in Pułtusk in 1794 declined to obey Prussian orders and started their march towards Kraków. This marked the start of the Kościuszko Uprising. Prussian rule lasted only a few years.

Under the partitions

Another Battle of Pułtusk was fought on 26 December 1806, between forces of Imperial Russia and Imperial France. The battle became so famous that its name is inscribed on the Arc de Triomphe in Paris. After the fall of Warsaw in 1809, Pułtusk became the temporary capital of the Duchy of Warsaw. After the fall of Napoléon Bonaparte, the town became part of so-called Congress Poland within the Russian Partition of Poland.

During the November Uprising, the town changed hands several times. In 1831 Russian forces were carrying a cholera epidemic when they entered the town, resulting in high fatalities. Pułtusk inhabitants took part also in the January Uprising. Afterwards the town was utterly destroyed and Russian officials sent many prominent citizens to Siberia and internal exile. On 30 January 1868 a meteorite fell in Pułtusk. It was one of the biggest to fall in Europe. Large chunks (9 kg (20 lb) each) were acquired by the British Museum, which has them on display in London.

Although, the first Jews settled in the town in the 15th century, the Jewish community only started to flourish in the 19th century after a large influx of Jews. At the start of the 19th century, about 120 Jews lived in the city. Others lived in shtetls outside the city. Throughout the 19th century, though, the Jewish population increased rapidly to nearly 7,000 in the mid-19th century as a result of Russian discriminatory policies and the expulsion of Jews from Russia to Russian-controlled Congress Poland (see Pale of Settlement).

The great fire in 1875 destroyed most of the city. It was depicted by Nobel Laureate Henryk Sienkiewicz in his novel Quo Vadis as the great fire of Rome.

By the year 1900, around 6,000 Jews lived in Pułtusk. Many had migrated to nearby Warsaw before and after World War I. Others emigrated to the United States. Following the war, the Jewish population rose to about 7,500 and accounted for roughly half of the total population of the town.

During the First World War Pultusk was the scene of another battle on 13 July 1915 when German forces attempted to cross the river Narew at Pułtusk. The 40th Infantry Division and the 50th Infantry Division of the imperial Russian Army successfully prevented them.[3]

Interbellum and World War II

The town was reintegrated with Poland, when the country regained independence following World War I in 1918. During the Polish-Soviet War, it was fiercely defended by Poles on August 9–10, 1920,[4] at the eve of the Battle of Warsaw. On August 13, the Russians captured the town, and then they massacred captured Polish soldiers.[4] On August 17, the Polish 9th Infantry Division recaptured the town.[4] In the interbellum the Polish 13th Infantry Regiment was stationed in Pułtusk. In 1931 the town had some 16,800 inhabitants.

As a result of the German invasion of Poland, which started World War II in September 1939, Pułtusk was occupied by the Wehrmacht and incorporated into Nazi Germany. Already on September 12–13, 1939, the Einsatzgruppe V entered the town to commit atrocities against the population.[5] Nazi Germany operated a police prison, court prison[6] and forced labour camp in the town.[7] The German police carried out executions of Poles in the local prison in November and December 1939.[8] During the German occupation, approximately 50% of the city's inhabitants, mostly Jews, were expelled or deported, some to Nazi concentration camps.[9] In 1941-1945 it was renamed in German as Ostenburg, to erase traces of Polish origin. On December 17, 1942, the Gestapo carried out a public execution of four members of the Home Army, the leading Polish resistance organization.[10] In the battle for Pułtusk during later World War II, over 16,000 soldiers of the Soviet Red Army were killed. As a result of the battle, approximately 85% of the city was destroyed.

On September 7, 1939, the city became under the control of Nazi Germany. On September 27, the Germans deported most of the Jews to concentration camps. Some eventually made their way to the Soviet border but many died in the camps. In the 21st century, descendants of Pułtusk Jewry are found mainly in Israel, the United States, Canada, and Argentina.

Modern times

In 1950, a rail line connecting Pułtusk with Nasielsk Railway Station was built.

In 1975, the Science Center of the Mazovian Center for Scientific Research was opened in the town.[11]

In 1993, Pułtusk hosted the first ever biennial meeting of the World International Advisory Committee of UNESCO's Memory of the World Programme to discuss and inscribe items onto the Register.[12]

Points of interest

Currently Pułtusk is one of the most picturesque towns of Masovia. Located on the Narew river, it is one of the most popular weekend places for residents of Warsaw. Points of interest include:

- Collegiate Church of Annunciation

- Small Gothic church with unique Renaissance stuccos

- The Old Town market (reputedly the longest market square in Europe)[13]

- Town Hall with 15th century Tower (it now houses a Regional Museum)[14]

- Polonia Castle (now operated as a hotel named Dom Polonii)

- Ogródek Jordanowski, one of the first children's playgrounds in Poland

- Monument to murdered Jewish residents of Pułtusk. The population of Pułtusk included approximately 9,000 Jews in 1939 before the Holocaust in Poland

- Soviet military cemetery

Education

Sports

The local football club is Nadnarwianka Pułtusk. It competes in the lower leagues.

International relations

Twin towns — Sister cities

Ganderkesee, Germany

Ganderkesee, Germany Montmorency, France

Montmorency, France New Britain, United States

New Britain, United States Senica, Slovakia

Senica, Slovakia Szerencs, Hungary

Szerencs, Hungary

Notes and references

- "Pułtusk w liczbach". polskawliczbach.pl (in Polish). Retrieved 9 July 2023.

- "Local history - Information about the town - Pułtusk - Virtual Shtetl". Archived from the original on 31 March 2017. Retrieved 30 March 2017.

- Oleinikov, Alexey Vladimirovich. "Наревская операция 1915 г. Ч. 2. Битва за плацдармы". btgv.ru. Битва гвардий. Retrieved 6 May 2022.

- Kowalski, Andrzej (1995). "Miejsca pamięci związane z Bitwą Warszawską 1920 r.". Niepodległość i Pamięć (in Polish). Muzeum Niepodległości w Warszawie (2/2 (3)): 151. ISSN 1427-1443.

- Wardzyńska, Maria (2009). Był rok 1939. Operacja niemieckiej policji bezpieczeństwa w Polsce. Intelligenzaktion (in Polish). Warszawa: IPN. p. 54.

- Wardzyńska, p. 224

- "Arbeitserziehungslager Ostenburg". Bundesarchiv.de (in German). Retrieved 12 December 2020.

- Wardzyńska, p. 223

- Gilbert, Martin (15 May 1987). The Holocaust: A History of the Jews of Europe During the Second World War. Macmillan. ISBN 9780805003482. Retrieved 30 March 2017 – via Google Books.

- "17 grudnia 1942 – Pułtusk pamięta!". pultusk24.pl (in Polish). 17 December 2018. Retrieved 12 December 2020.

- Chludziński, Tomasz; Żmudziński, Janusz (1978). Mazowsze, mały przewodnik. Warsaw: Sport i turystyka. pp. 205–209.

- "Memory of the World Resources". Retrieved 7 September 2022.

- (in Polish) Nasze Miasto - Pułtusk (History of Pułtusk), Pułtusk Academy of Humanities (Akademia Humanistyczna im. Aleksandra Gieysztora in Pułtusk)

- (in Polish) Atrakcje Pułtuska Retrieved 24 September 2022.

- "Miasta partnerskie" (in Polish). Retrieved 7 September 2022.