National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific

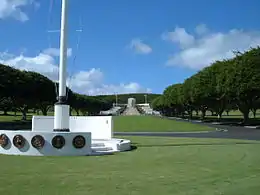

The National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific (informally known as Punchbowl Cemetery) is a national cemetery located at Punchbowl Crater in Honolulu, Hawaii. It serves as a memorial to honor those men and women who served in the United States Armed Forces, and those who have been killed in doing so. It is administered by the National Cemetery Administration of the United States Department of Veterans Affairs and is listed on the National Register of Historic Places. Millions of visitors visit the cemetery each year, and it is one of the most popular tourist attractions in Hawaii.

| National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific | |

|---|---|

National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific. | |

| Details | |

| Established | 1949 |

| Location | |

| Country | United States |

| Coordinates | 21°18′46″N 157°50′47″W |

| Type | United States National Cemetery |

| Owned by | National Cemetery Administration |

| No. of graves | >61,000 |

| Website | https://www.cem.va.gov/cems/nchp/nmcp.asp |

| Find a Grave | National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific |

.JPG.webp)

.JPG.webp)

.JPG.webp)

.jpg.webp)

Location, construction and history

Punchbowl Crater was formed some 75,000 to 100,000 years ago during the Honolulu period of secondary volcanic activity. A crater resulted from the ejection of hot lava through cracks in the old coral reefs which, at the time, extended to the foot of the Ko'olau Mountain Range.

Although there are various translations of the Punchbowl's Hawaiian name, "Puowaina," the most common is "Hill of Sacrifice." This translation closely relates to the history of the crater. The first known use was as an altar where Hawaiians offered human sacrifices to pagan gods and the killed violators of the many taboos. Later, during the reign of Kamehameha the Great, a battery of two cannons was mounted at the rim of the crater to salute distinguished arrivals and signify important occasions. Early in the 1880s, leasehold land on the slopes of the Punchbowl opened for settlement and in the 1930s, the crater was used as a rifle range for the Hawaii National Guard. Toward the end of World War II, tunnels were dug through the rim of the crater for the placement of shore batteries to guard Honolulu Harbor and the south edge of Pearl Harbor.

During the late 1890s, a committee recommended that the Punchbowl become the site for a new cemetery to accommodate the growing population of Honolulu. The idea was rejected for fear of polluting the water supply and the emotional aversion to creating a city of the dead above a city of the living. Fifty years later, Congress authorized a small appropriation to establish a national cemetery in Honolulu with two provisions: that the location be acceptable to the War Department, and that the site would be donated rather than purchased. In 1943, the governor of Hawaii offered the Punchbowl for this purpose. The $50,000 appropriation proved insufficient, however, and the project was deferred until after World War II. By 1947, Congress and veteran organizations placed a great deal of pressure on the military to find a permanent burial site in Hawaii for the remains of thousands of World War II servicemen on the island of Guam awaiting permanent burial. Subsequently, the Army again began planning the Punchbowl cemetery.

In February 1948, Congress approved funding and construction began on the national cemetery. Since the cemetery was dedicated on September 2, 1949, approximately 53,000 World War II, Korean War, and Vietnam War veterans and their dependents have been interred. The cemetery now almost exclusively accepts cremated remains for above-ground placement in columbaria; casketed and cremated remains of eligible family members of those already interred there may, however, be considered for burial.

Prior to the opening of the cemetery for the recently deceased, the remains of soldiers from locations around the Pacific Theater—including Guam, Wake Island, and Japanese POW camps—were transported to Hawaii for final interment. The first interment was made January 4, 1949. The cemetery opened to the public on July 19, 1949, with services for five war dead: an unknown serviceman, two Marines, an Army lieutenant and one noted civilian war correspondent Ernie Pyle. Initially, the graves at National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific were marked with white wooden crosses and Stars of David—like the American cemeteries abroad—in preparation for the dedication ceremony on the fourth anniversary of V-J Day. Eventually, over 13,000 soldiers and sailors who died during World War II would be laid to rest in the Punchbowl. Despite the Army's extensive efforts to inform the public that the star- and cross-shaped grave markers were only temporary, an outcry arose in 1951 when permanent flat granite markers replaced them.

A new 25-bell carillon built by Schulmerich Carillons, Inc. was dedicated in 1956 during Veteran's Day services. The carillon is nicknamed "Coronation" and was funded in part by the Pacific War Memorial Commission and individual contributions. Arthur Godfrey helped to raise funds.[1]

The National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific was the first such cemetery to install Bicentennial Medal of Honor headstones, the medal insignia being defined in gold leaf. On May 11, 1976, a total of 23 of these were placed on the graves of medal recipients, all but one of whom were killed in action.

In August 2001, about 70 generic "Unknown" markers for the graves of men known to have died during the attack on Pearl Harbor were replaced with markers that included USS Arizona (BB-39) after it was determined they perished on this vessel. In addition, new information that identified grave locations of 175 men whose graves were previously marked as "Unknown" resulted in the installation of new markers in October 2002.

The National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific contains a "Memorial Walk" that is lined with a variety of memorial markers from various organizations and governments that honor America's veterans. As of 2012, there were 60 memorial boulders (bearing bronze plaques) along the pathway. Additional memorials can be found throughout the National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific—most commemorating soldiers of 20th-century wars, including those killed at Pearl Harbor.

Updates and improvements

In 2015, Congress allotted $25 million in funds for improvements, maintenance and expansion of the cemetery. The goal was to make the cemetery worth visiting for both tourists and local as well as highly advanced for the members and officers of the military.

The design-build project of this national cemetery consisted of many improvements both inside and outside including construction of the Memorial Wall, replacement of columbarium caps at courts 1–5 inside the cemetery, demolishing the existing Administration and PIC building, construction of Columbarium Court 13, which included 6,860 columbarium niches, repair of existing roadways, and replacement of existing signage, followed by site furnishing, landscaping, irrigation, and site utilities and achieving a LEED silver rating by the US Green Building Council.

The project was awarded to Nan Inc by the Department of Veterans Affairs for $25,100,445.

The cemetery is currently undergoing a major construction project to build additional columbarium space.

The National Park service and National Memorial Cemetery

During the Civil War, the U.S. government feared for the sanctity of the graves of fallen Union soldiers and issued General Orders No. 33, of April 3, 1862, Moving to give federal protection to Union grave sites pushing The Act of July 17, 1862, which gave the President the authority, “whenever in his opinion it shall be expedient, to purchase cemetery grounds and cause them to be securely enclosed, to be used as a national cemetery for the soldiers who shall die in the service of the country. To further protect the sites of fallen heroes congress approves of the "Reburial Program" on April 13, 1866, stating the Secretary of War is hereby authorized and required to take immediate measures to preserve the graves of soldiers of the United States who fell in battle and secure suitable burial places in which they may be properly interred; and to have the grounds enclosed, so that the resting-places of the honored dead may be kept sacred forever followed on February 22, 1867, with an “Act to establish and to protect National Cemeteries.” This was followed on July 1, 1870, by an Act of Congress authorizing the United States to take title to any national cemeteries where the States had given their consent, and on May 18, 1872, by an Act authorizing the Secretary of War to appoint superintendents. Still, more action was needed such as The Yosemite and Yellowstone Acts (1889,90), The Lacy Act (1900), The Antiquities Act (1906), and The Organic Act (1916) which leads to President Woodrow Wilson signing the act creating the National Park Service, a new federal bureau in the Department of the Interior on August 25, 1916, which encompasses all locations protected by the previous acts.

The National Park Service has managed national cemeteries since 1972 and all were transferred from the War Department to the Department of the Interior by Executive Order 6228 of July 28, 1933.

"Operation Glory" and the Punchbowl Cemetery

After their retreat in 1950, dead soldiers and Marines were buried at a temporary military cemetery near Hungnam, North Korea. During Operation Glory, which occurred from July to November 1954, the dead of each side were exchanged; remains of 4,167 US soldiers/Marines were exchanged for 13,528 North Korean/Chinese dead. In addition 546 civilians who died in United Nations prisoner of war camps were turned over to the South Korean Government.[2] After "Operation Glory" 416 Korean War "unknowns" were buried in the Punchbowl Cemetery. According to one report,[3] 1,394 names were also transmitted during "Operation Glory" from the Chinese and North Koreans (of which 858 names proved to be correct); of the 4,167 returned remains were found to be 4,219 individuals of whom 2,944 were found to be Americans of whom all but 416 were identified by name. Of 239 Korean War unaccounted for: 186 not associated with Punchbowl unknowns (176 were identified and of the remaining 10 cases four were non-Americans of Asiatic descent; one was British; three were identified and two cases unconfirmed).[4] Fifty-seven years after the Korean War, remains of two of the "Punchbowl unknowns" were identified—both from the 1st Marine Division. One was Pfc. Donald Morris Walker of Support Company/1st Service Battalion/1st Marine Division who was KIA December 7, 1950[5] and the other was Pfc. Carl West of Weapons Company/1st Battalion/7th Regiment/1st Marine Division who was KIA December 10, 1950.[6]

In 2011 remains of an unknown USAF pilot from Operation Glory were identified from the "Punchbowl Cemetery";[7] POW remains from "Operation Glory" were also identified in 2011.[8][9]

From 1990 to 1994, North Korea excavated and turned over 208 sets of remains—possibly containing remains of 200–400 US servicemen—but few identifiable because of co-mingling of remains.[10] In 2011 remains were identified.[11]

From 1996 to 2006, 220 remains were recovered near the Chinese border. In 2008, a total of 63 were identified (26 World War II; 19 Korea; 18 Vietnam)[12] (Among those identified: January 2008 remains of a Michigan soldier.[13] In March 2008, remains of an Indiana soldier[14] and an Ohio soldier were identified). According to a report June 24, 2008, of 10 Korean War remains disinterred from the "Punchbowl Cemetery" six have been identified.[15] From January to April 2009, a total of twelve Unknowns have been identified—three from World War II; eight from Korean War; one from Vietnam.[16] In 2011 remains returned in 2000 were identified.[17]

Wreaths Across America at the Punchbowl Cemetery

On December 17, 2022, at 12:00 pm, the Women's Marines Association HI-2 Wahine Koa Chapter will be helping the National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific (Punchbowl) to Remember and Honor our veterans by laying Remembrance wreaths on the graves of our country's fallen heroes. WMA HI-2 Wahine Koa Chapter sponsors the event annually to honor and remember as many fallen heroes as possible by sponsoring remembrance wreaths and volunteering on Wreaths Day. Wreaths can be sponsored by donating at Wreaths Across America.

Honolulu Memorial

In 1964, the American Battle Monuments Commission erected the Honolulu Memorial at the National Memorial Cemetery "to honor the sacrifices and achievements of American Armed Forces in the Pacific during World War II and in the Korean War". The memorial was later expanded in 1980 to include the Vietnam War. The names of 28,788 military personnel who are missing in action or were lost or buried at sea in the Pacific during these conflicts are listed on marble slabs in ten Courts of the Missing which flank the Memorial's grand stone staircase.

The Honolulu Memorial is one of three war memorials in the United States administered by the American Battle Monuments Commission; the others are the East Coast Memorial to the Missing of World War II in New York and the West Coast Memorial to the Missing of World War II in San Francisco.

The dedication stone at the base of staircase is engraved with the following words:

- IN THESE GARDENS ARE RECORDED

- THE NAMES OF AMERICANS

- WHO GAVE THEIR LIVES

- IN THE SERVICE OF THEIR COUNTRY

- AND WHOSE EARTHLY RESTING PLACE

- IS KNOWN ONLY TO GOD

At the top of the staircase in the Court of Honor is a statue of Lady Columbia, also known as Lady Liberty, or Justice. Here she is reported to represent all grieving mothers. She stands on the bow of a ship holding a laurel branch. The inscription below the statue, taken from Abraham Lincoln's letter to Mrs. Bixby, reads:

- THE SOLEMN PRIDE

- THAT MUST BE YOURS

- TO HAVE LAID

- SO COSTLY A SACRIFICE

- UPON THE ALTAR

- OF FREEDOM

In popular culture

The statue is featured in the opening sequence of both the 1970s television series Hawaii Five-O and its 2010 remake. The latter series has also filmed at the cemetery several times—John McGarrett, the father of lead character Steve McGarrett, is a Vietnam War veteran and is buried there.[18]

Notable interments and memorials

- Medal of Honor recipients

- William R. Caddy (1925–1945), World War II †

- George H. Cannon (1915–1941), World War II †

- Anthony P. Damato (1922–1944), World War II †

- William G. Fournier (1913–1943), World War II †

- Barney F. Hajiro (1916–2011), World War II

- William D. Halyburton Jr. (1924–1945), World War II †

- Mikio Hasemoto (1916–1943), World War II †

- Louis J. Hauge Jr. (1924–1945), World War II †

- William D. Hawkins (1914–1943), World War II †

- Shizuya Hayashi (1917–2008), World War II

- Edwin J. Hill (1894–1941), World War II †

- Daniel Inouye (1924–2012), World War II, Hawaii's first congressman (1959–63) and US Senator (1963–2012)

- Yeiki Kobashigawa (1917–2005), World War II

- Robert T. Kuroda (1922–1944), World War II †

- Larry L. Maxam (1948–1968), Vietnam War †

- Martin O. May (1922–1945), World War II †

- Robert H. McCard (1918–1944), World War II †

- Leroy A. Mendonca (1932–1951), Korean War †

- Kaoru Moto (1917–1992), World War II

- Joseph E. Muller (1908–1945), World War II †

- Masato Nakae (1917–1998), World War II

- Shinyei Nakamine (1920–1944), World War II †

- Allan M. Ohata (1918–1977), World War II

- Joseph W. Ozbourn (1919–1944), World War II †

- Herbert K. Pililaau (1928–1951), Korean War †

- Thomas James Reeves (1895–1941), World War II †

- Joseph Sarnoski (1915–1943), World War II †

- Elmelindo Rodrigues Smith (1935–1967), Vietnam War †

- Grant F. Timmerman (1919–1944), World War II †

- Francis B. Wai (1917–1944), World War II †

- Benjamin F. Wilson (1921–1988), Korean War

- Rodney J. T. Yano (1943–1969), Vietnam War †

- Other notables

- Darr H. Alkire (1903–1977) Air Force Brigadier General, Senior Officer in Command of the West Compound at Stalag Luft III Prisoner of War Camp

- Donn Beach (1907–1989), born Ernest Raymond Beaumont Gantt, founder of Don the Beachcomber restaurants and inventor of the tiki bar

- John A. Burns (1909–1975), second state governor of Hawaii (1962–74)

- John "Jack" Chevigny (1906–1945), Notre Dame football player (said, "that's one for the Gipper" in 1928 game) who was killed on Iwo Jima †

- Ralph Waldo Christie (1893–1987), Navy admiral involved with torpedo and submarine operations before and during World War II

- Norman "Sailor Jerry" Collins (1911–1973), prominent Honolulu tattoo artist

- Stanley Armour Dunham (1918–1992), grandfather of United States President Barack Obama

- Frank F. Fasi (1920–2010), six term mayor of the City and County of Honolulu

- Henry Oliver "Hank" Hansen (1919–1945), original Iwo Jima flag raiser †

- Jasper Holmes (1900–1986) US Naval Intelligence analyst

- John J. Hyland (1912–1998), admiral and commander of the Pacific Fleet during Vietnam

- Douglas Kennedy (1915–1973), actor

- Young-Oak Kim (1919–2005), member of the 442nd Regimental Combat Team and first Asian-American to command a battalion in wartime

- Wah Kau Kong (1919–1944), First Chinese-American fighter pilot †

- Spark Matsunaga (1916–1990), US Senator from Hawaii, member of the 442nd Regimental Combat Team

- Patsy Mink (1927–2002), US Congresswoman from Hawaii and co-author of Title IX

- Ellison Onizuka (1946–1986), first astronaut from Hawaii, killed in the Space Shuttle Challenger disaster

- Ernie Pyle (1900–1945), World War I veteran and Pulitzer Prize-winning World War II war correspondent †

- William F. Quinn (1919–2006), territorial governor (1957–59) and first state governor of Hawaii (1959–62)

- Thomas Rienzi (1919–2010), Army Signal Corps lieutenant general and communications-electronics innovator

- Kent Rogers (1923–1944), actor and impressionist †

- Harold Sakata (1920–1982), professional wrestler and actor

- Leo Sharp (1924–2016), World War II veteran, horticulturist, and drug courier

- James Shigeta (1929–2014), actor

- Charles L. Veach (1944–1995), USAF fighter pilot and NASA astronaut

See also

References

- "Hawaii Volcano Crater has new 25-bell Carillon" (PDF). The Diapason. 47 (3): 6. February 1, 1956.

- "Korean War Exchange of Dead – Operation GLORY". Qmmuseum.lee.army.mil. Archived from the original on December 28, 2007. Retrieved November 13, 2013.

- "Korean War POW/MIA Network Operation Glory". Koreanwarpowmia.net. Archived from the original on July 23, 2011. Retrieved October 25, 2013.

- DPMO Archived April 27, 2011, at the Wayback Machine

- Chris Kenning. "ID of Korean War remains may end family's wait". The Courier-Journal. Archived from the original on May 16, 2021. Retrieved May 15, 2021 – via Leatherneck.com.

- Marine Corps News, "Forgotten War Vet Remembered In Eternity", Oct. 4, 2007; Story ID#: 2007109124338, By Gunnery Sgt. Will Price Archived May 29, 2011, at the Wayback Machine

- "DPMO news release" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on September 26, 2012. Retrieved November 13, 2013.

- "DPMO news release" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on November 8, 2011. Retrieved November 13, 2013.

- "DPMO news release" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on September 26, 2012. Retrieved November 13, 2013.

- "JPAC – Wars And Conflicts". Jpac.pacom.mil. July 29, 2008. Archived from the original on November 11, 2013. Retrieved November 13, 2013.

- "DPMO News release" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on September 26, 2012. Retrieved November 13, 2013.

- News Releases Archived May 2, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- "DPMO News release" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on September 26, 2012. Retrieved November 13, 2013.

- "Remains from Korea identified as Indiana soldier – Army News, opinions, editorials, news from Iraq, photos, reports". Armytimes.com. Retrieved November 13, 2013.

- Archived December 17, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- Archived January 14, 2009, at the Wayback Machine & Archived June 4, 2011, at the Wayback Machine &

- "DPMO news release" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on September 26, 2012. Retrieved November 13, 2013.

- Burbridge, Wendie (June 27, 2015). "Five-O Redux: On location in Hawaiʻi". Honolulu Pulse. Archived from the original on June 30, 2018. Retrieved June 30, 2018.

Further reading

- Sledge, Michael (2005). Soldier Dead: How We Recover, Identify, Bury, and Honor Our Military Fallen. Columbia University Press. ISBN 0231135149. OCLC 81452881.

- "Factsheet: POW March Routes and U.N. Cemeteries". Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency. November 24, 2020. Retrieved May 11, 2022.

External links

- U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs: National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific

- eGuide to National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific

- "Honolulu Memorial, National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific" (PDF). American Battle Monuments Commission Honolulu Memorial. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 23, 2006. Retrieved December 2, 2006.

- U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific

- National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific at Find a Grave

- Honolulu Memorial at Find a Grave (the Courts of the Missing, located in the National Memorial)

- The short film Staff Film Report 66-20A (1966) is available for free viewing and download at the Internet Archive.

- Historic American Buildings Survey (HABS) No. HI-3, "National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific, 2177 Puowaina Drive, Honolulu, Honolulu County, HI", 43 photos, 4 photo caption pages