Mahasthangarh

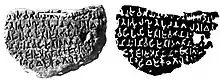

Mahasthangarh (Bengali: মহাস্থানগড়, Môhasthangôṛ) is one of the earliest urban archaeological sites discovered thus far in Bangladesh. The village Mahasthan in Shibganj upazila of Bogra District contains the remains of an ancient city which was called Pundranagara or Paundravardhanapura in the territory of Pundravardhana.[1][2][3] A limestone slab bearing six lines in Prakrit in Brahmi script recording a land grant, discovered in 1931, dates Mahasthangarh to at least the 3rd century BCE.[4][5] It was an important city under the Maurya Empire. The fortified area was in use until the 8th century CE.[2]

মহাস্থানগড় | |

Ramparts of the Mahasthangarh citadel | |

Shown within Bangladesh Rajshahi division  Mahasthangarh (Bangladesh)  Mahasthangarh (South Asia) | |

| Location | Mahasthan, Bogra District, Rajshahi Division, Bangladesh |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 24°57′40″N 89°20′34″E |

| Type | Settlement |

| History | |

| Founded | Not later than 3rd century BC |

| Abandoned | 8th century AD |

| History of Bangladesh |

|---|

|

|

|

Etymology

Mahasthan means a place that has excellent sanctity and garh means fort. Mahasthan was first mentioned in a Sanskrit text of the 13th century entitled Vallalcharita. It is also mentioned in an anonymous text Karatoya mahatmya, circumstantially placed in 12th–13th century. The same text also mentions two more names to mean the same place – Pundrakshetra, land of the Pundras, and Pundranagara, city of the Pundras. In 1685, an administrative decree mentioned the place as Mastangarh, a mixture of Sanskrit and Persian meaning fortified place of an auspicious personage. Subsequent discoveries have confirmed that the earlier name was Pundranagara or Paundravardhanapura, and that the present name of Mahasthangarh is of later origin.[6]

Geography

Mahasthangarh (Pundranagar), the ancient capital of Pundravardhana is located 11 km (6.8 mi) north of Bogra on the Bogra-Rangpur highway, with a feeder road (running along the eastern side of the ramparts of the citadel for 1.5 km) leading to Jahajghata and site museum.[7] Buses are available for Bogra from Dhaka and take 41⁄2 hours for the journey via Bangabandhu Jamuna Bridge across the Jamuna River. Buses are available from Bogra to Mahasthangarh. Rickshaws are available for local movement. Hired transport is available at Dhaka/ Bogra. Accommodation is available at Bogra.[8] When travelling in a hired car, one can return to Dhaka the same day, unless somebody has a plan to visit Somapura Mahavihara at Paharpur in the district of Naogaon and other places, or engage in a detailed study.

It is believed that the location for the city in the area was decided upon because it is one of the highest areas in Bangladesh. The land in the region is almost 36 metres (118 ft) above sea level, whereas Dhaka, the capital of Bangladesh, is around 6 metres (20 ft) above sea level. Another reason for choosing this place was the position and size of the Karatoya, which as recently as in the 13th century was three times wider than Ganges.[9]

Mahasthangarh stands on the red soil of the Barind Tract which is slightly elevated within the largely alluvium area. The elevation of 15 to 25 metres above the surrounding areas makes it a relatively flood free physiographic unit.[10]

Discovery

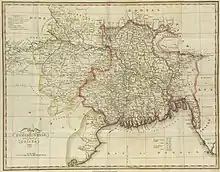

Several personalities contributed to the discovery and identification of the ruins at Mahasthangarh. Francis Buchanan Hamilton was the first to locate and visit Mahasthangarh in 1808, C.J.O'Donnell, E.V.Westmacott, and Beveridge followed. Alexander Cunningham was the first to identify the place as the capital of Pundravardhana. He visited the site in 1879.[6]

On 19 April 2004, The Daily Star reported that locals were looting bricks and valuables from the site. They were also building residences on the site ignoring government regulations.[11]

Citadel

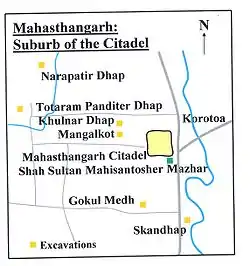

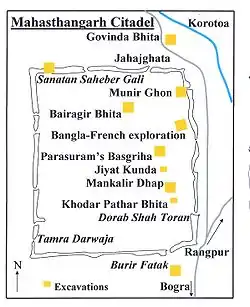

The citadel (see map alongside), the fortified heart of the ancient city, is rectangular in plan, measuring roughly 1.523 kilometres (0.946 mi) long from north to south, and 1.371 kilometres (0.852 mi) from east to west, with high and wide ramparts in all its wings. Area of the citadel is approximately 185 ha.[9] The Karatoya, once a mighty river but now a small stream, flows on its east.[2]

Till the 1920s, when excavations started, the inside of the citadel was higher than the surrounding areas by over 4 metres and was dotted with several straggling elevated pieces of land. The rampart looked like a jungle clad mud rampart with forced openings at several points. The rampart was 11–13 metres (36–43 ft) higher than the surrounding area. At its south-east corner stood a mazhar (holy tomb). A later day mosque (built in 1718–19) was also there.[6]

At present there are several mounds and structural vestiges inside the fortifications. Of these a few of note are: Jiat Kunda (well which, according to legends, has life giving power), Mankalir Dhap (place consecrated to Mankali), Parasuramer Basgriha (palace of a king named Parasuram), Bairagir Bhita (palace of a female anchorite), Khodar Pathar Bhita (place of stone bestowed by God), and Munir Ghon (a bastion). There are some gateways at different points: Kata Duar (in the north), Dorab Shah Toran (in the east), Burir Fatak (in the south), and Tamra Dawaza (in the west)[2] At the north-eastern corner there is a flight of steps (a later addition) that goes by the name of Jahajghata. A little beyond Jahajghata and on the banks of the Karatoya is Govinda Bhita (a temple dedicated to Govinda). In front of it is the site museum, displaying some of the representative findings. Beside it is a rest house.

Suburb of the citadel

Besides the fortified area, there are around a hundred mounds spread over an area with a radius of 9 km. (See map alongside).

Excavated mounds:[2]

- Gobhindo Bhita, a temple close to the north-eastern corner of the citadel

- Khulnar Dhap, a temple 1 km north of the citadel

- Mangalkot, a temple 400m south of Khulnar Dhap

- Godaibari Dhap, a temple 1 km south of Khulnar Dhap

- Totaram Panditer Dhap, a monastery 4 km north-west of the citadel

- Noropotir Dhap (Vashu Bihara), a group of monasteries 1 km north-west of Totaram Ponditer Dhap (said to be the place where Po-shi-po Bihara mentioned by Xuanzang (Hieun Tsang) was located)

- Gokul Medh (Lokhindorer Bashor Ghor), a temple 3 km south of the citadel

- Shkonder Dhap, a temple 2 km south-east of Gokul Medh

Major unexcavated mounds:[2]

- Shiladebir Ghat

- Chunoru Dighi Dhap

- Kaibilki Dhap

- Juraintala

- Poroshuramer Shobhabati

- Balai Dhap

- Prochir Dhibi

- Kanchir Hari Dhibi

- Lohonar Dhap

- Khujar Dhap

- Doshatina Dhap

- Dhoniker Dhap

- Mondirir Dorgah

- Bishmordana Dhibi

- Malinar Dhap

- Malpukuria Dhap

- Jogir Dhap

- Podmobhatir Dhap

- Kanai Dhap

- Dulu Mojhir Bhita

- Podda Debhir Bhita

- Rastala Dhap

- Shoshitola Dhap

- Dhonbandhor Dhap

- Chader Dhap

- Shindinath Dhap

- Shalibahon Rajar Kacharibari Dhipi

- Kacher Angina

- Mongolnather Dhap

- ChhoutoTengra/ Babur Dhap/ Kethar Dhap

- Boro Tengra/ Shonyashir Dhap

.jpg.webp) entrance of mahasthangarh

entrance of mahasthangarh

Excavations

Systematic archaeological excavation of Mahasthangarh was first started in 1928–29 under the guidance of K.N.Dikshit of the Archaeological Survey of India. The areas around Jahajghata, Munir Ghon and Bairagir Bhita were explored. Excavation was resumed in 1934–36 at Bairagir Bhita and Govinda Bhita. Excavation was carried out in 1960s around the Mazhar, Parasuramer Prasad, Mankalir Dhap, Jiat Kunda and in a part of the northern rampart. In the next phase excavation was carried out sporadically in parts of the east and north ramparts but the final report is yet to be published. In the period 1992–98 excavation was conducted in the area lying between Bairagir Bhita and the gateway exposed in 1991 as a Bangla-Franco joint venture, which is now in its second phase with excavation around the mazhar in the western side of the citadel.[12]

Movable antiquities

The excavations have led to the recovery of a large number of items, a few of which are listed here.

Inscriptions: A 4.4 cm x 5.7 cm limestone slab bearing six lines in Prakrit in Brahmi script, discovered accidentally by a day labourer in 1931 was an important find. The text appears to be a royal order of Magadh, possibly during the rule of Asoka. It dates the antiquity of Mahasthangarh to 3rd century BC. An Arabic inscriptional slab of 1300–1301 discovered in 1911–12 mentions the erection of a tomb in honour of Numar Khan, who was a Meer-e-Bahar (lieutenant of the naval fleet). A Persian inscriptional slab of 1718–19 records the construction of a mosque during the reign of the Mughal Emperor Farrukhsiyar.[13]

Coins: Silver punch marked coins are datable to a period between the 4th century BC and the 1st–2nd century AD. Some uninscribed copper cast coins have been found. Two Gupta period coins have been reported from a nearby village named Vamanpara. A number of coins belonging to the sultans of 14th–15th century and British East India Company have been found.[13]

Ceramics: Mostly represented by a vast number of shards.[13]

Sculpture: A 5th century Buddha stone sculpture recovered from Vasu Vihara, a Lokesvara stone sculpture showing blending of Vishnu and Avalokiteśvara, salvaged from neighbouring Namuja village, a number sandstone door-frames, pillars and lintels (datable to 5th–12th century), numerous Buddha bronze sculpture datable to 10th–11th century, a terracotta Surya discovered at Mankalir Bhita, and numerous other pieces.[13]

Terracotta Plaques: A number of terracotta plaques have been discovered.

Many of these are on display in the site museum, which is open Sunday to Thursday summer:10 am to 6 pm, winter:9 am to 5 pm. Recess:1–2 pm, Friday recess is from 12.30 to 2.30, opens at 9 am in summer, other timings same. Summer timings 1 April to 30 September, winter timings 1 October to 30 March.[2] Books on Mahasthangarh and other archaeological sites in Bangladesh (in Bengali and English) are available at the ticket counter for the site museum.

Highlights of some excavated sites

Inside the citadel

Bairagir Bhita: Constructed/ reconstructed in four periods: 4th–5th century AD, 6th–7th century, 9th–10th century, and 11th century. Excavations have revealed impoverished base ruins resembling temples. Two sculptured sandstone pillars have been recovered.[14]

Khodarpathar Bhita: Some pieces of stone carved with transcendent Buddha along with devotees in anjali (kneeling with folded hands) recovered.[14]

Parasuramer Prasad: Contains remains of three occupation periods – 8th century AD findings include stone Visnupatta of Pala period, 15th- 16th century findings include some glazed shreds of Muslim origin, and the third period has revealed two coins of the British East India Company issued in 1835 and 1853.[14]

Mankalir Dhap: terracotta plaques, bronze Ganesha, bronze Garuda etc. were discovered. Base ruins of a 15-domed mosque (15th–16th century) was revealed.[14]

Bangla-Franco joint venture: Excavations have revealed 18 archaeological layers, ranging from 5th century BC to 12th century AD, until virgin soil at a depth of around 17 m.[14]

Outside the citadel

Govinda Bhita: Situated 185 m north-east of Jahajghata and opposite the site museum. Remains dated from 3rd century BC to 15th century AD. Base remains of two temples have been exposed.[14]

Totaram Panditer Dhap: Situated in the village Vihara, about 6 km north-west of the citadel. Structural remains of a damaged monastery have been exposed.[14]

Narapatir Dhap: Situated in the village Basu Vihara, 1.5 km north-west of Totaram Panditer Dhap. Base remains of two monasteries and a temple have been exposed. Cunningham identified this place as the one visited by Xuanzang (Hiuen Tsang) in the 7th century AD.[14]

Gokul Medh: Also known as Behular Basar Ghar or Lakshindarer Medh, situated in the village Gokul, 3 km to the south of the citadel, off the Bogra-Rangpur road, connected by a narrow motorable road about 1 km. Excavations in 1934–36 revealed a terraced podium with 172 rectangular blind cells. It is dated 6th–7th century. Local mythology associates it with legendary Lakshmindara-Behula. The village Gokul also has several other mound Kansr Dhap has been excavated.[14]

Skandher Dhap: Situated in village Baghopara on the Bogra-Rangpur road, 3.5 km to the south of the citadel, a sandstone Kartika was found and structural vestiges of a damaged building were revealed. It is believed to be the remains of Skandha Mandira (temple consecrated to Kartika), mentioned in Karatoya mahatmya, as well as Kalhan's Rajatarangin, written in 1149–50. There also are references to Skandhnagara as a suburb of Pundranagara. Baghopara village has three other mounds.[14]

Khulnar Dhap: Situated in village Chenghispur, 700 m west of the north-west corner of the citadel has revealed remains of a temple. The mound is named after Khullana, wife of Chand Sadagar.[14]

From the present findings it can be deduced that there was a city called Pundravardhana at Mahasthangarh with a vast suburb around it, on all sides except the east, where the once mighty Karatoya used to flow. It is evident that the suburbs of Pundravardhana extended at least to Baghopara on the south-west, Gokul on the south, Vamanpara on the west, and Sekendrabad on the north.[15] However, the plan of the city and much of its history are still to be revealed.[16]

.jpg.webp)

Bhimer Jangal This well-known embankment starts from the north-east corner of Bogra town and proceeds northwards for about 30 miles to a marshy place called Damukdaher bit, under police station Govindaganj (Rangpur District) and it is said, goes oil to Ghoraghat. It is made of the red earth of the locality and retains at places even now a height of 20 feet above the level of the country. There is a break ill it of over three miles from Daulatpur (north west of Mahasthan-garh) to Hazaradighi (south-west, of it). About a mile south of Hazradighi. the stream Subil approaches the jangal and runs alongside it down to Bogra town.

Some people think that the Subil is a moat formed by digging the earth for the jangal but as there is no embankment on the northern reach of the Subil now called the Ato nala. which merges in the Kalidaha bil; north of Mahasthan-garh O'Donnell was probably right in saying that the Subil represents the western of the two branches into which the Karatoya divided above Mahasthan.

On the Bogra-Hazradighi section of the jangal, there are two cross embankments running down to the Karatoya, about 2 miles and 4 miles respectively north of Bogra town and there is a diagonal embankment connecting these cross bonds and then running along the Karatoya until it meets the main embankment near Bogra.

This jangal or embankment appears to have been of a military character, thrown up to protect the country on its east. The break roar Mahasthan may be due to the embankment having been washed away or to the existence of natural protection by the bit.

The Bhima to whom the embankment is ascribed may be the Kaivarta chief of the eleventh century who according to the Ramcharitam ruled over Varendra in succession to his father Rudraka and uncle Divyoka, who had ousted king Mahipala II of the Pala, dynasty. Bhima in his turn was defeated in battle and billed by Ramapala. Mahipala's son.

Jogir Bhaban South west of Bagtahali (beyond Chak Bariapara) and some 3 miles west of the khetlal road is a settlement of the Natha sect of Saiva sannyasis, known as Yogir-bhavan, forming the eastern section of Arora village. An account of this settlement is given by Beveridge, J.:1.S.T., 1878; p. 94. It occupies about so, bighas of land and forms the headquarters of the sect. of which there are branches at Yogigopha and Gorakh-kui, both in the Dinajpur District, the former in its south-west part some 5 miles west of Paharpur, J.A.S.B.1875, p. 189, and the latter in its north-west part some 4 miles west of Nekmardan.

The shrines at Yogir-bhavan are situated in the south-west corner of an en¬closure or-math. One of them called Dharmma-dungi, bears a brick inscription, reading scrvva-siddha sana 1148 Sri Suphala ... (the year =1741 A.D.). 'In front of it is another shrine called 'Gadighar,' where a fire is kept burn at all hours. Outside the enclose are four temples, dedicated respectively to Kalabhai¬rava, Sarvamangala Durga and Gorakshanatha. The Kalabhairava temple contains a diva linga and bears a brick inscription reading Sri Ramasiddha sana 1173 sala (=1766 A.D.) ample Sri Jayanatha Nara-Narayana. The Sarva¬mangala temple contains three images of Hara-Gauri, one of Mahishamardini, a fragment of an Ashta-matrika slab, a fragment of a three-faced female figure probably Ushnishavijava (Sadhanamala; II. pl. XIV) and a four-armed female figure playing on a vina (evidently Sarasvati, but worshipped here as Sarva¬ mangala). Over the entrance is a brick inscription reading 1089 Meher Natha sadaka sri Abhirama Mehetara (the year =1681 A.D.). In the Durga temple is a stone image of Chamunda, and in the Gorakshanatha one, a Siva lihga. There are three brick built samadhis near the latter temple.

Arora South-west of the Dadhisugar and standing on the Masandighi, in Arora village; is Salvan Rajar bari referred to under Baghahali. This Silvan may possibly be the same as king Salavahan, son of Sahila-deva of the Chamba inscription who won the title of Kari-ghata-varsha (= hunjara-ghata-varsha ?) (R. C. Majumdar, vange kambojadhikara,' vanga-rani, Chaitara, 1330.B.S.p. 251, ind. Ant, XVII.pp. 7–13). Beveridge refers to this mound in JA.S.B., 1878, p 95.

This name of Sahila seems, to occur again in Sahiladitya lakshmam in v. 10 of the Silimpllr inscription (Ep. Ind, XIII, p. 291). If this identification is correct, then the word kaunjanraghatacarshcna in the Bangarh stone inscription (Gauda-raja-mala, p. 35) is really the title or virudha of the Gudapati of the Kumboja family and not the date of the inscription.

Teghar North of Chandnia that the road skirts the bil and comes to Teghar village Which juts out into the bil 'Near about here are several mounds; such as Naras¬patir dhap. Kacher Angina (or glazed courtyard, a term applied to many ruins in these parts) etc. The biggest of these mounds, Mangal-nather dhap, (Fig. 6) is situated close to the point, from which a road branches off to Bihar. It is said that terracotta plaques as well as stone images were found at this site, but were all consigned to the neighbouring dighi.

Rojakpur Proceeding westward along the road from Gokul to Haripur, we pass into the western arm of the latter village, already referred to. and meet the Bogra¬ Khetlal road near the Chandnia hat. West of Haripur and south of the Somrai bil is the village of Rojakpur, into which, as already stated, the elevated ground from Chandnia hat extends. On this ground are two mounds called respectively Chandbhita. (probably referring to the Manasa legend) and Dhanbhandar. A little further west is another mound called Singhinath Dhap.

Mathura East of Bumanpara and extending up to the garh on the east and the Kalidaha bill on the north, is the village of Mathura, in Which there are several tank and on a ridge overlooking the Gilatala moat, two mounds called Parasuramer Sabhabati and Yogir Dhap.

Threats to Mahasthangarh

In a 2010 report titled Saving Our Vanishing Heritage, Global Heritage Fund identified Mahasthangarh as one of 12 worldwide sites most "On the Verge" of irreparable loss and damage, citing insufficient management (poor water drainage in particular) and looting as primary causes.[17]

Anecdote

There is a local legend that Shah Sultan Balkhi Mahisawar arrived at Pundravardhana in the garb of a fakir (mystic holy pedlar of Islamic philosophy) riding a fish. (Mahisawar is Persian word meaning a 'person who rides a fish'). He came from Balkh in Afghanistan with a retinue. The period of his arrival is variably put at 5th century AD, 11th century AD and 17th century AD. At that time there was a king named Parasuram with his seat and palace in Mahasthangarh. Mahisawar requested Parasuram for a piece of land to spread his prayer mat on which he could pray. The request was granted but the prayer mat started expanding as soon as it was laid on the ground. When the prayer mat reached the area around the palace bewildered Parasuram declared war. In the beginning the battle seemed to be favouring Parasuram. A scavenger Harapala informed Mahisawar that it was difficult to defeat the royal troops because of the pool called Jiat Kunda. A dead soldier bathed in the waters of Jiat Kunda came back to life. On knowing this Mahisawar asked a kite to drop a piece of beef in Jiat Kunda. When this was done, the pool lost its powers. The royal troops were on the verge of defeat. The commander of the royal troops, Chilhan, with a large number of his followers, went over to Mahisawar. Thereafter Parasuram and many members of the royal family committed suicide.[7] There are many variations of this anecdote, some of which are sold in Bengali booklets in and around Mahasthangarh/Pundravardhana.

Some antiquity comparisons

Mahasthangarh dates back to at least 3rd century BC and is acknowledged as the earliest city-site discovered thus far in Bangladesh. Somapura Mahavihara at Paharpur in Naogaon District was once the biggest Buddhist monastery south of the Himalayas. It dates from the 8th century AD. Mainamati ruins in Comilla District date back to 6th–13th centuries AD.[8] In neighbouring West Bengal, the ruins of Pandu Rajar Dhibi on the banks of the Ajay River in Bardhaman district date back to 2000 BC. However, this recent archaeological discovery has not yet been properly studied by outside experts and specialists in this field, and as such the historical value of many of the statements must be considered as uncertain.[18] The ruins at Chandraketugarh in 24 Parganas South and Rajbadidanga in Murshidabad district date back to the early years of the Christian era.[19]

Buddhist Viharas

- Somapura Vihara

- Halud Vihara

- Vasu Vihara

- Ananda Vihara

- Sitakot Vihara[20]

Gallery

Boundary wall of Mahasthangarh

Boundary wall of Mahasthangarh Ornamental stone carving on display at Mahasthangarh

Ornamental stone carving on display at Mahasthangarh.jpg.webp) Mankalir Mound

Mankalir Mound Govinda Bhita just outside the Mahasthangarh citadel

Govinda Bhita just outside the Mahasthangarh citadel.jpg.webp) Place of Parshuram

Place of Parshuram Karatoya River by the Mahasthangarh citadel

Karatoya River by the Mahasthangarh citadel Lakshindar Behular Basar Ghar at Gokul

Lakshindar Behular Basar Ghar at Gokul Gokul Medh

Gokul Medh Gokul Medh

Gokul Medh Mahasthangarh

Mahasthangarh Mahasthangarh

Mahasthangarh Govinda Vita

Govinda Vita Govinda Vita

Govinda Vita.jpg.webp) Govinda Vita

Govinda Vita.JPG.webp) Mahasthangarh Museum

Mahasthangarh Museum.JPG.webp) Mahasthangarh Museum

Mahasthangarh Museum.JPG.webp) Mahasthangarh Museum

Mahasthangarh Museum Place of Parshuram

Place of Parshuram.jpg.webp) Bihar Dhap

Bihar Dhap.JPG.webp) Mahasthangarh Museum

Mahasthangarh Museum Mahasthangarh Museum

Mahasthangarh Museum

.jpg.webp) mahasthangarh wall

mahasthangarh wall.jpg.webp) resort of mahashangarh

resort of mahashangarh.jpg.webp) wall of mahasthangarh

wall of mahasthangarh.jpg.webp) mahasthangarh

mahasthangarh.jpg.webp) distance view

distance view.jpg.webp) mahasthangarh

mahasthangarh.jpg.webp) Mahasthangarh

Mahasthangarh.jpg.webp) mahasthangarh wall

mahasthangarh wall

See also

References

- Hossain, Md. Mosharraf (2006). "Preface". Mahasthan: Anecdote to History. Dhaka: Dibyaprakash. ISBN 978-984-483-245-9.

- Brochure: Mahasthan – the earliest city-site of Bangladesh, published by the Department of Archaeology, Ministry of Cultural Affairs, Government of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh, 2003

- Majumdar, R. C. (1971). History of Ancient Bengal. Calcutta: G. Bhardwaj & Co. pp. 5, 13. OCLC 961157849.

- Sastri, Hirananda (1931). Epigraphia Indica vol.21. pp. 83–89.

- Hossain, Md. Mosharraf, pp. 56–60.

- Hossain, Md. Mosharraf, pp. 16–19

- Hossain, Md. Mosharraf, pp. 14–15.

- Mc Adam, Marika, Bangladesh, Lonely Planet

- "Mahasthangarh". Wondermondo.

- Chowdhury, Sifatul Quader (2012). "Mahasthangarh, Physical Setup". In Islam, Sirajul; Jamal, Ahmed A. (eds.). Banglapedia: National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Second ed.). Asiatic Society of Bangladesh.

- Ali, Anwar; Rahman, Hasibur. "Plunderers destroy Mahasthan Garh". The Daily Star. Retrieved 18 April 2021.

- Hossain, Md. Mosharraf, pp. 21–23.

- Hossain, Md. Mosharraf, pp. 56–65.

- Hossain, Md. Mosharraf, pp. 25–46.

- Hossain, Md. Mosharraf, p. 67.

- Hossain, Md. Mosharraf, p. 76.

- "Global Heritage in the Peril: Sites on the Verge". Global Heritage Fund. Archived from the original on 20 August 2012. Retrieved 9 November 2015.

- Majumdar, R.C., pp. 20–21

- Majumdar, R.C., pp. 530, 540

- Le, Huu Phuoc (2010). Buddhist Architecture. Grafikol. p. 71. ISBN 978-0-9844043-0-8.

External links

- Alam, Shafiqul (2012). "Mahasthan". In Islam, Sirajul; Jamal, Ahmed A. (eds.). Banglapedia: National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Second ed.). Asiatic Society of Bangladesh.

- Explore Mahasthangarh with Google Earth on Global Heritage Network