Quiche Lorraine

Quiche Lorraine is a French tart with a filling made of cream, eggs, and bacon or ham, in an open pastry case. It was little known outside the French region of Lorraine until the mid-20th century. As its popularity spread, nationally and internationally, the addition of cheese became commonplace, although it was criticised as inauthentic. The dish may be served hot, warm or cold.

Quiche Lorraine served in Paris | |

| Type | Savoury |

|---|---|

| Place of origin | France |

| Region or state | Lorraine |

| Main ingredients | Pastry case filled with egg, cream and bacon |

History

According to Larousse Gastronomique, quiches (sometimes spelled kiches) originated in the eastern French region Lorraine. The name may derive from the German Kuchen, a term used for similar dishes.[1] There are many varieties of quiche, and Larousse comments that every region of Alsace and Lorraine has its own and maintains it is the only authentic version of the dish.[1] Originally a quiche Lorraine was baked with a bread-dough case similar to that now used for pissaladières and pizzas,[2] but in modern versions shortcrust or puff pastry is generally used.[1] The dish dates back to the 16th century,[2] but until well into the 20th century it was little known outside its region of origin, and was as seldom seen in Paris as in foreign countries.[3]

Ingredients

The classic ingredients for the filling are eggs, thick cream, and ham or bacon (in strips or lardons), made into a savoury custard.[1] Elizabeth David in her French Provincial Cooking (1960) and Simone Beck, Louisette Bertholle and Julia Child in their Mastering the Art of French Cooking (1961) excluded cheese from their recipes for quiche Lorraine,[4] and David in particular was scornful of cooks and manufacturers who added it. She considered they did so for reasons of cost and convenience rather than taste: a classic quiche Lorraine, with only a cream, egg and bacon filling, is "quite tricky to get right".[5]

David placed the responsibility for the inauthentic addition of cheese with Parisian chefs. In 1870 Jules Gouffé introduced a version to which he added Parmesan,[5] and in 1903 Auguste Escoffier recommended lining the pastry case with bacon and strips of Gruyère before adding the cream and egg mixture.[6] Attempts were made to restore the simplicity of the original dish: in 1901 Le Figaro printed a recipe that excluded not only cheese but also bacon,[7] and in 1904 André Theuriet and a fellow native of Lorraine, Edmond Richardin, published another recipe that included neither bacon nor cheese,[8] but in 1932 Marcel Boulestin, a highly influential restaurateur and writer, specified the addition of grated Gruyère,[5] and by the 1950s the use of cheese had become commonplace as the popularity of quiche Lorraine grew.[9] David cited a London cookery school where the students were taught to use evaporated milk and processed Cheddar for their fillings.[9] La Mère Brazier's standard recipe for the dish excluded cheese, but she thought variations permissible, "replac[ing] the lardons and the ham with a layer of sliced Roquefort ... or with thin slices of goose or duck liver and fresh truffle".[10]

Among some recent versions of the dish, Anne-Sophie Pic's adds Comté,[11] and Delia Smith's adds both Cheddar and Parmesan.[12] No cheese is used in the versions by Lindsey Bareham, Felicity Cloake, Alain Ducasse, Simon Hopkinson, Thomas Keller and Dan Lepard.[13][14] Ready-made quiches Lorraines sold in supermarkets in France, Britain and the US typically contain cheese – usually Emmental or similar, although British versions often contain Cheddar.[n 2]

Notes, references and sources

Notes

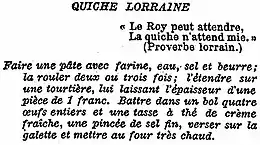

- Opening quotation: "The King can wait; the quiche can't" − Lorraine proverb. Recipe: Make a dough with flour, water, salt and butter; roll it two or three times; spread it on a pie dish, leaving it the thickness of a 1 franc coin [approx. 14mm]. In a bowl, beat four whole eggs and a teacup of fresh cream, a pinch of fine salt, pour over the pastry and cook in a very hot oven.

- Quiches Lorraines sold by Picard Surgelés in 2022 contained 11.6% "Emmental français", and those from Monoprix 3.1% Emmental français.[15] In Britain, the stronger Cheddar was prevalent, constituting 15% of the quiche from Waitrose and 9% of that from Marks and Spencer (with a further 8% of Emmental).[16] Ready-made American quiches Lorraines contained unrevealed quantities of "Grand Cru Cheese" (cultured pasteurised milk, salt, enzymes, potato starch and powdered cellulose) from Whole Foods Market, and unspecified Swiss cheese in Nancy's version.[17]

References

- Montagné, p. 797

- David (2008), p. 186

- "Quiche Lorraine", The Yorkshire Evening Post, 24 May 1926, p. 3; and "New Vintage Wines", The Times, 7 July 1931, p. 12

- Beck et al, p. 158; and David (2008), p. 186

- David (2001), p. 117

- Escoffier, p. 115

- "Le concours culinaire du Figaro" Le Figaro, 19 August 1901, p. 6

- David (2001), p. 118

- David (2001), p. 115

- Brazier et al, p. 86

- "La recette de quiche lorraine d’Anne-Sophie Pic" Archived 2022-02-19 at the Wayback Machine, Le Figaro, 20 March 2020

- Smith, p. 272

- Cloake, Felicity. "How to cook perfect quiche Lorraine" Archived 2022-05-10 at the Wayback Machine. The Guardian, 26 May 2011

- Ducasse, Alan. "Quiche Lorraine" Archived 2021-06-25 at the Wayback Machine, All My Chefs. Retrieved 16 May 2022

- "Quiche Lorraine" Archived 2021-04-21 at the Wayback Machine, Picard; and "Quiche Lorraine" Archived 2020-11-30 at the Wayback Machine, Monoprix. Retrieved 16 May 2022

- "Quiche Lorraine" Archived 2021-04-12 at the Wayback Machine, Waitrose; and "Quiche Lorraine" Archived 2022-05-16 at the Wayback Machine, Marks and Spencer. Retrieved 16 May 2022

- "Quiche Lorraine" Archived 2021-06-17 at the Wayback Machine, Whole Foods Market; and "Quiche Lorraine" Archived 2021-09-20 at the Wayback Machine, Nancy's. Retrieved 16 May 2022

- David (2008), pp. 18 and 187

- Beck et al, p. 153

Sources

- Beck, Simone; Louisette Bertholle; Julia Child (2012) [1961]. Mastering the Art of French Cooking, Volume One. London: Particular. ISBN 978-0-241-95339-6.

- Brazier, Eugénie; Moreau, Roger; Bocuse, Paul; Pacaud, Bernard (2015) [2004]. La Mère Brazier: The Mother of Modern French Cooking. Translated by Drew Smith. London: Modern Books. ISBN 978-1-906761-84-4.

- David, Elizabeth (2001). Is There a Nutmeg in the House?. London: Viking. ISBN 978-0-7540-2446-0.

- David, Elizabeth (2008) [1960]. French Provincial Cooking. London: Folio Society. OCLC 809349711.

- Escoffier, Auguste (1903). Le guide culinaire: aide-mémoire de cuisine pratique. Paris: Art culinaire. OCLC 1202722258.

- Montagné, Prosper (1976). Larousse gastronomique. London: Hamlyn. OCLC 1285641881.

- Smith, Delia (2008). How to Cheat at Cooking. London: Ebury. ISBN 978-0-09-192229-0.