Quran translations

Translations of the Qurʻan are considered interpretations of the scripture of Islam in languages other than Arabic. The Qurʻan was originally written in the Arabic language and has been translated into most major African, Asian and European languages.[1]

| Quran |

|---|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Translation |

|---|

|

| Types |

| Theory |

| Technologies |

| Localization |

| Institutional |

|

| Related topics |

|

Islamic theology

Translation of the Qurʻan from Arabic into other languages has always been a difficult issue in Islamic theology. Because Muslims revere the Qurʻan as miraculous and inimitable (iʻjaz al-Qurʻan), they argue that the Qurʻanic text should not be isolated from its true language or written form, at least not without keeping the Arabic text with it.[1]

According to Islamic theology, the Qurʻan is a revelation very specifically in Arabic, and so it should only be recited in Quranic Arabic. Translations into other languages are necessarily the work of humans and so, according to Muslims, no longer possess the uniquely sacred character of the Arabic original. Since these translations necessarily subtly change the meaning, they are often called "interpretations"[2] or "translation[s] of the meanings" (with "meanings" being ambiguous between the meanings of the various passages and the multiple possible meanings with which each word taken in isolation can be associated, and with the latter connotation amounting to an acknowledgement that the so-called translation is but one possible interpretation and is not claimed to be the full equivalent of the original). For instance, Pickthall called his translation The Meaning of the Glorious Koran rather than simply The Koran.

The task of translation of the Qurʻan is not an easy one; some native Arab speakers will confirm that some Qurʻanic passages are difficult to understand even in the original Arabic script. A part of this is the innate difficulty of any translation; in Arabic, as in other languages, a single word can have a variety of meanings.[2] There is always an element of human judgement involved in understanding and translating a text. This factor is made more complex by the fact that the usage of words has changed a great deal between classical and modern Arabic. As a result, even Qurʻanic verses which seem perfectly clear to native Arab speakers accustomed to modern vocabulary and usage may have an original meaning that is not obvious.

The original meaning of a Qurʻanic passage will also be dependent on the historical circumstances of the prophet Muhammad's life and the early community in which it originated. Investigating that context usually requires a detailed knowledge of hadith and sirah, which are themselves vast and complex texts. This introduces an additional element of uncertainty that cannot be eliminated by any linguistic rules of translation.

History

The first translation of the Qurʻan was performed by Salman the Persian, who translated surah al-Fatiha into the Middle Persian in the early seventh century.[3] According to Islamic tradition contained in the hadith, the Negus of the Ethiopian Empire and the Byzantine Emperor Heraclius received letters from Muhammad containing verses from the Qurʻan. However, during Muhammad's lifetime, no passage from the Qurʻan was ever translated into these languages nor any other.[1]

The second known translation was into Greek and was used by Nicetas Byzantius, a scholar from Constantinople, in his 'Refutation of Qurʻan' written between 855 and 870. However, we know nothing about who and for what purpose had made this translation. It is said that it was a complete translation.[4]

The first fully attested complete translations of the Qurʻan were done between the 10th and 12th centuries into Classical Persian. The Samanid emperor, Mansur I (961–976), ordered a group of scholars from Khorasan to translate the Tafsir al-Tabari, originally in Arabic, into Persian. Later in the 11th century, one of the students of Khwaja Abdullah Ansari wrote a complete tafsir of the Qurʻan in Persian. In the 12th century, Najm al-Din 'Umar al-Nasafi translated the Qurʻan into Persian. The manuscripts of all three books have survived and have been published several times.

In 1936, translations in 102 languages were known.[1]

Latin

.jpg.webp)

Robertus Ketenensis produced the first Latin translation of the Qurʻan in 1143.[1] His version was entitled Lex Mahumet pseudoprophete ("The law of Mahomet the false prophet"). The translation was made at the behest of Peter the Venerable, abbot of Cluny, and currently exists in the Bibliothèque de l'Arsenal in Paris. Ketenensis' work was republished in 1543 in three editions by Theodore Bibliander at Basel. All editions contained a preface by Martin Luther. Many later European translations of the Qurʻan merely translated Ketenensis' Latin version into their own language, as opposed to translating the Qurʻan directly from Arabic.

In the early thirteenth century, Mark of Toledo made another, more literal, translation into Latin, which survives in several manuscripts. In the fifteenth century, Juan of Segovia produced another translation in collaboration with the Mudejar writer, Isa of Segovia. Only the prologue survives. In the sixteenth century, Juan Gabriel Terrolensis aided Cardenal Eguida da Viterbo in another translation into Latin. In the early seventeenth century, another translation was made, attributed to Cyril Lucaris.

Louis Maracci (1612–1700), a teacher of Arabic at the Sapienza University of Rome and confessor to Pope Innocent XI, issued a second Latin translation in 1698 in Padua.[5] His edition contains the Qurʻan's Arabic text with a Latin translation, annotations to further understanding and – embued by the time's spirit of controversy – an essay titled "Refutation of the Qurʻan", where Marracci disproves Islam from the then Catholic point of view. Despite the Refutation's anti-Islamic tendency, Marracci's translation is accurate, suitably commented, and quotes many Islamic sources.[6]

Marracci's translation too became the source of other European translations (one in France by Savory, and one in German by Nerreter). These later translations were quite inauthentic, and one even claimed to be published in Mecca in 1165 AH.[1]

Modern languages

The first translation in a modern European language was in Castilian Spanish or Aragonese by the convert Juan Andrés (or so he claims in his Confusión o Confutación de la secta mahomética y del alcorán) but this translation is lost. A few dozen Qurʻan verses into Castilian are found within the Confusión itself. There were lost translations in Catalan, one of them by Francesc Pons Saclota in 1382, the other appeared in Perpignan in 1384.[7] Another Romance translation was made into Italian, 1547 by Andrea Arrivabene, derived from Ketenensis'. The Italian translation was used to derive the first German translation Salomon Schweigger in 1616 in Nuremberg, which in turn was used to derive the first Dutch translation in 1641.[1]

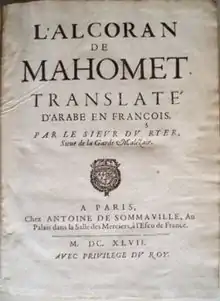

The first French translation came out in 1647, and again in 1775, issued by André du Ryer. The Du Ryer translation also fathered many re-translations, most notably an English version by Alexander Ross in 1649. Ross' version was used to derive several others: a Dutch version by Glazemaker, a German version by Lange.[1]

Adyghe

- The first Adyghe translation of the Quran was done by Iskhak Mashbash. A Kabardian edition was also published. It was translated from Russian.

Modern Greek

The first Modern Greek translation was done by Gerasimos Pentakis in 1886, after receiving royal approval from George I of Greece. A second edition was published in 1928. Another three were published in 1958, 1980 and 2002, the most recent was done from Persa Koumoutsi. There is also an online translation. In Greek, there is also the 9th century translation of Nicetas Byzantios referred earlier in the article.

French

L'Alcoran de Mahomet / translaté d'Arabe François par le Sieur Du Ryer, Sieur de la Garde Malezair., 1647, 1649, 1672, 1683, 1719, 1734, 1770, 1775, by André Du Ryer, was the first French translation. This was followed two centuries later in Paris by the 1840 translation by Kasimirski who was an interpreter for the French Persian legation. Then in the mid-twentieth century, a new translation was done by Régis Blachère a French Orientalist followed a few years later in 1959 by the first translation by a Muslim into the French Language from the original Arabic. This work of Muhammad Hamidullah continues to be reprinted and published in Paris and Lebanon as it is regarded as the most linguistically accurate of all translations although critics may complain there is some loss of the spirit of the Arabic original.

Russian

In 1716, Pyotr Postinkov published the first translation of the Quran in Russian based on the French translation of André du Ryer. Gordiy Sablukov published the first Russian translation of the Quran from the original Arabic text in 1873.[8] Nearly 20 translations in Russian have been published.

Spanish

There are four complete translations of the Qurʻan in modern Spanish that are commonly available.

- Julio Cortes translation 'El Coran' is widely available in North America, being published by New York-based Tahrike Tarsile Qurʻan publishing house.

- Ahmed Abboud and Rafael Castellanos, two converts to Islam of Argentine origin, published 'El Sagrado Coran' (El Nilo, Buenos Aires, Argentina, 1953).

- Kamel Mustafa Hallak fine deluxe hardback print 'El Coran Sagrado' is printed by Maryland-based Amana Publications.

- Abdel Ghani Melara Navio a Spaniard who converted to Islam in 1979, his 'Traduccion-Comentario Del Noble Coran' was originally published by Darussalam Publications, Riyadh, in December 1997. The King Fahd Printing Complex has its own version of this translation, with editing by Omar Kaddoura and Isa Amer Quevedo.

English

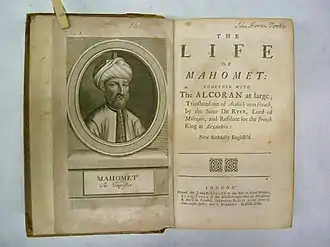

The earliest known translation of the Qurʻan in any European language was the Latin works by Robert of Ketton at the behest of the Abbot of Cluny in c. 1143. This translation remained the only one until 1649 when the first English language translation was done by Alexander Ross, chaplain to King Charles I, who translated from a French work L'Alcoran de Mahomet by du Ryer.

In 1734, George Sale produced the first translation of the Qurʻan direct from Arabic into English but relying heavily on O.M.D. Louis Maracci's Vatican Quran,[9] Since then, there have been English translations by the clergyman John Medows Rodwell in 1861, and Edward Henry Palmer in 1880, both showing in their works several mistakes of mistranslation and misinterpretation, which brings into question their primary aim. These were followed by Richard Bell in 1937 and Arthur John Arberry in the 1950s.

The Qurʻan (1910) by Mirza Abul Fazl (1865–1956), a native of East Bengal (now Bangladesh), later moved to Allahabad, India. He was the first Muslim to present a translation of the Qurʻan into English along with the original Arabic text. Among the contemporary Muslim scholars, Abul Fazl was a pioneer who took interest in the study of the chronological order of the Qurʻan and drew the attention of Muslim scholars to its importance.

With the increasing population of English-speaking Muslims around the start of the 20th century, three Muslim translations of the Qurʻan into English made their first appearance. The first was Muhammad Ali's 1917 translation, which is composed from an Ahmadiyya perspective, with some small parts being rejected as unorthodox by the vast majority of Muslims. This was followed in 1930 by the English convert to Islam Marmaduke Pickthall's more literalist translation.

Soon thereafter in 1934, Abdullah Yusuf Ali, published his translation, featuring copious explanatory annotation – over 6000 notes, generally being around 95% of the text on a given page, to supplement the main text of the translation. This translation has gone through over 30 printings by several different publishing houses, and is one of the most popular amongst English-speaking Muslims, alongside the Pickthall and Saudi-sponsored Hilali-Khan translations.[10]

With few new English translations over the 1950–1980 period, these three Muslim translations were to flourish and cement reputations that were to ensure their survival into the 21st century, finding favor among readers often in newly revised updated editions. Orientalist Arthur Arberry's 1955 translation and native Iraqi Jew N. J. Dawood's unorthodox translation in 1956 were to be the only major works to appear in the post-war period. A. J. Arberry's The Koran Interpreted remains the scholarly standard for English translations, and is widely used by academics.[10]

The English translation of Kanzul Iman is called The Treasure of Faith, which is translated by Farid Ul Haq. It is in simple, easy-to-understand modern-day English. Explanations are given in brackets to avoid ambiguity, provide better understanding and references to similar verses elsewhere.

Syed Abdul Latif's translation published in 1967, is regarded highly by some. He was a professor of English at Osmania University, Hyderabad. It was nevertheless short-lived due to criticism of his foregoing accuracy for the price of fluency.

The Message of the Qurʻan: Presented in Perspective (1974) was published by Hashim Amir Ali. He translated the Qurʻan into English and arranged it according to chronological order. Hashim Amir-Ali (1903-c. 1987) was a native of Salar Jung, Hyderabad State in the Deccan Plateau. In 1938, he came under the influence of Abul Fazl and took a deep interest in the study of the Qurʻan, and was aware of the significance of the chronological order of the passages contained in it.

Another Jewish convert to Islam, Muhammad Asad's monumental work The Message of The Qur'an made its appearance for the first time in 1980.

Professor Ahmed Ali's Al-Qurʻan: A Contemporary Translation (Akrash Publishing, Karachi, 1984, Reprinted by Oxford University Press, Delhi, 1987; Princeton University Press, New Jersey, 1988, with 9th reprinting 2001). Fazlur Rahman Malik of the University of Chicago writes, "It brings out the original rhythms of the Qurʻanic language and the cadences. It also departs from traditional translations in that it gives more refined and differentiated shades of important concepts". According to Francis Edward Peters of New York University, "Ahmed Ali's work is clear, direct, and elegant – a combination of stylistic virtues seldom found in translations of the Qurʻan. His is the best I have read".

At the cusp of the 1980s, the 1973 oil crisis, the Iranian Revolution, the Nation of Islam and a new wave of cold-war-generated Muslim immigrants to Europe and North America brought Islam squarely into the public limelight for the first time in Western Europe and North America. This resulted in a wave of translations as Western publishers tried to capitalize on the new demand for English translations of the Qurʻan. Oxford University Press and Penguin Books were all to release editions at this time, as did indeed the Saudi Government, which came out with its own re-tooled version of the original Yusuf Ali translation. Canadian Muslim Professor T. B. Irving's 'modern English' translation (1985) was a major Muslim effort during that time.

Qurʻan: The Final Testament, Islamic Productions, Tucson, Arizona, (1989) was published by Rashad Khalifa (رشاد خليفة; 19 November 1935 – 31 January 1990) Khalifa wrote that he was a messenger of God and that the archangel Gabriel 'most assertively' told him that chapter 36, verse 3, of the Qurʻan, 'specifically' referred to him.[11][12] He is referred to as God's Messenger of the Covenant by his followers.[13] He wrote that the Qurʻan contains a mathematical structure based on the number 19. He made the controversial claim that the last two verses of chapter nine in the Qurʻan were not canonical, telling his followers to reject them.[14] He reasoned that the verses disrupted an otherwise flawless nineteen-based pattern and were sacrilegious since they appeared to endorse worship of Muhammad. Khalifa's research received little attention in the West. In 1980, Martin Gardner mentioned it in Scientific American.[15] Gardner later wrote a more extensive and critical review of Khalifa and his work.[16]

The arrival of the 1990s ushered in the phenomenon of an extensive English-speaking Muslim population well-settled in Western Europe and North America. As a result, several major Muslim translations emerged to meet the ensuing demand. One of them was published in 1990, and it is by the first woman to translate the Qurʻan into English, Amatul Rahman Omar, together with her husband, Abdul Mannan Omar.[17] In 1991 appeared an English translation under the title: The Clarion Call Of The Eternal Qur-aan, by Muhammad Khalilur Rahman (b. 1906–1988), Dhaka, Bangladesh. He was the eldest son of Shamsul Ulama Moulana Muhammad Ishaque of Burdwan, West Bengal, India, – a former lecturer of Dhaka University.

In 1996 the Saudi government financed a new translation "the Hilali-Khan Qurʻan" which was distributed free worldwide by the Saudi government. It has been criticized for being in line with their particular interpretation.[18]

The Saheeh International Qurʻan translation was published in 1997 in Sa'udi Arabia by three women converts. It remains extremely popular.

In 1999, a fresh translation of the Qurʻan into English entitled The Noble Qurʻan – A New Rendering of its Meaning in English by Abdalhaqq and the American Aisha Bewley was published by Bookwork,[19] with revised editions being published in 2005[20] and 2011.[21]

In 2000, The Majestic Qur'an: An English Rendition of Its Meanings was published by a committee of four Turkish Sunni scholars who have divided the work as follows: Nureddin Uzunoğlu translated Surahs (chapters) 1 to 8; Tevfik Rüştü Topuzoğlu: 9 to 20; Ali Özek: 21 to 39; Mehmet Maksutoğlu: 40 to 114. The translation comes with an extensive commentary and annotations in modern standard English, makes it easier to understand than the older translations.

The Qurʻan in Persian and English (Bilingual Edition, 2001) features an English translation by the Iranian poet and author Tahereh Saffarzadeh. This was the third translation of the Qurʻan into English by a woman, after Amatul Rahman Omar,[22] and Aisha Bewley – and the first bilingual translation of the Qurʻan.[23][24][25]

In 2003, the English translation of the 8-volume Ma'ariful Qur'an was completed and the translation of the Qurʻan used for it was newly done by Muhammad Taqi Usmani in collaboration with his brother Wali Raazi Usmani and his teachers, Professors Hasan Askari and Muhammad Shameem.

In 2004, a new translation of the Qurʻan by Muhammad Abdel-Haleem was also published, with revised editions being published in 2005[26] and 2008.[27]

In 2006, The Qur'an with Annotated Interpretation in Modern English by Ali Ünal was published. The work is more like a simplified tafsir (Qur'anic exegesis) than a translation. He uses modern English, and adds short notes between brackets amidst the translation when needed.

In 2007, Qurʻan: a Reformist Translation by Edip Yüksel, Layth Saleh al-Shaiban, and Martha Schulte-Nafeh, was published.

In 2007, The Meanings of the Noble Qurʻan with Explanatory Notes by Muhammad Taqi Usmani was published. It has been published in 2 volumes at first and later, in a single volume. He also translated the Qurʻan in simple Urdu, making him a translator of the Qurʻan in dual languages.

In 2007 The Sublime Qurʻan appeared by Laleh Bakhtiar; it is the second translation of the Qurʻan by an American woman.[23][28][29][30]

In 2008, Tarif Khalidi completed The Qur'an: A New Translation for Penguin Classics and Viking Press. It did not include commentary, so as to give readers a sense of how the earliest Muslims would have read and listened to the Qur'an. It serves as a replacement to Penguin Classics' older translation by NJ Dawood, although the Dawood translation remains in print.

In 2009, Wahiduddin Khan translated the Qurʻan in English, which was published by Goodword Books entitled The Qurʻan: Translation and Commentary with Parallel Arabic Text. This translation is considered as the easiest to understand due to simple and modern English. The pocket-size version of this translation with only English text is widely distributed as part of dawah work. [31][32]

A rhymed verse edition of the entire Qurʻan rendered in English by Thomas McElwain in 2010 includes rhymed commentary under the hardback title The Beloved and I, Volume Five, and the paperback title The Beloved and I: Contemplations on the Qurʻan.

In 2015, Mustafa Khattab of Al-Azhar University completed The Clear Qurʻan: A Thematic English Translation, after three years of collaboration with a team of scholars, editors, and proof-readers. Noted for its clarity, accuracy, and flow, this work is believed to be the first English translation done in Canada.[33]

A Turkish Scholar Hakkı Yılmaz worked on the Qurʻan through the root meanings of the Arabic words and published a study called Tebyin-ül Qurʻan, and he also published a Division by Division Interpretation in the Order of Revelation in Turkish. His work was translated into English.[34]

In 2018, Musharraf Hussain released The Majestic Quran: A Plain English Translation, a reader-friendly presentation of the translation of the Qurʻan aiming to help readers understand the topic being read, and learn the moving and transformative message of the Qurʻan. There are 1500 sections with headings. Approved by Dar al-Ifta' al-Misriyya (Egyptian institute of Fatwas).[35]

In 2019, Tahir Mahmood Kiani released The Easy Quran. It is the easiest English translation by far, rendered specifically for those whose level of English is simple and basic. The translator was bearing in mind ages 12 when translating, yet younger readers of ages 6 have found it just as simple and easy to understand.[36] Reviewers have described it as "the easiest readable, understandable Quran in English". The easy Quran is just as useful for both children and adults.

In 2021, Talal Itani released Quran in English: Super-easy to read. For ages 9 to 99. A Quran translation for children and adults.

In 2022, Nuh Ha Mim Keller released The Quran Beheld. Based on two integral study readings over fifteen years with a teacher,[37] it was described by a reviewer as “the first reliable plenary translation of the Quran into English.”

Asian languages

Sindhi

Sindhi was the first language to translate the Quran into Arabic language later also Sindhi script was changed to Arabic Script Akhund Azaz Allah Muttalawi (Urdu: آخوند أعزاز الله) (Sindhi: مولانا اعزاز اللہ )was a Muslim theologian from Sindh. Akhund Azaz is considered to be the first person who translated the Qurʻan from Arabic to Sindhi. According to Sindhi tradition the first translation was made by in 270 AH / 883 CE by an Arab scholar. later it was translated into the Sindhi language by Imam Abul Hassan bin Mohammad Sadiq Al-Sindhi Al-Ma

Hindi and Urdu

The first Modern Urdu translation was done by Shah Abdul Qadir, son of Shah Abdul Aziz Dehlawi, in 1826. A wide accepted translation of Quran in both Hindi and Urdu was done by Imam Ahmed Raza Khan in 1911 named as Kanzul Iman. One of the authentic translations of the Qurʻan in Urdu was done by Abul A'la Maududi and was named Tafhimu'l-Qur'an. Molana Ashiq Elahi Merathi also translated the Qurʻan in Urdu. Tafseer e Merathi is a renowned translation of Qurʻan along with tarsier and Shan e Nazool in Urdu by Ashiq Ilahi Bulandshahri, In 1961 Mafhoom-ul-Quran was written by Ghulam Ahmed Perwez.[38] In 1985, Maulana Wahiduddin Khan wrote the Urdu Translation and Commentary titled Tazkirul Quran. He also translated Quran in Hindi.[39][40] Arshad Madani & Pro Sulaiman translated Hindi Quran titled, Quran Sharif: Anuvad aur Vakhya in 1991. Irfan-ul-Qurʻan is an Urdu translation by Muhammad Tahir-ul-Qadri.[41] [Mutalaeh Qurʻan مطالعہ قرآن] by ABDULLAH, 2014, is an Urdu Translation .[42]

Bengali

In 1389, Shah Muhammad Sagir, one of the oldest poets of Bengali literature, was the first to translate surahs of the Quran into the old Bengali language.[43] Girish Chandra Sen, a Brahmo Samaj missionary, was the first person to produce a complete translation of the Qurʻan into the Bengali language in 1886, although an incomplete translation was made by Amiruddin Basunia in 1808.[44][45] Abbas Ali of Chandipur, West Bengal was the first Muslim to translate the entire Qurʻan into the Bengali language. Muhammad Naimuddin of Tangail translated the first ten chapters of the Qurʻan into Bengali in 1891.[46]

Besides many translated Qurʻanic exegesis are available in Bengali language.[47] Mohammad Akram Khan translated the 30th chapter of the Quran with commentary in 1926. In 1938, Muhammad Naqibullah Khan published a Bengali translation.[48] Muhiuddin Khan was also a known Bangladeshi who translated the Maʻarif al-Qurʻan into Bengali.

Gujarati

Imam Ahmed Raza Khan translated the first Gujarati Quran in 1911 called Kanzul Iman based on the Urdu Translation of Shah Abdul Qadir Dehlvi. Quran Majeed Gujarati Tarjuma Sathe by Ahmedbhai Sulaiman Jumani in 1930.[49] [31]

Tamil

Translated as Fathhur-Rahma Fi Tarjimati Tafsir al-Qurʻan (Qurʻan translation) By Sheikh Mustafa (1836 – 25 July 1888)Beruwala Sri Lanka; Later on Abdul Hameed Bhakavi Tamil Nadu- India

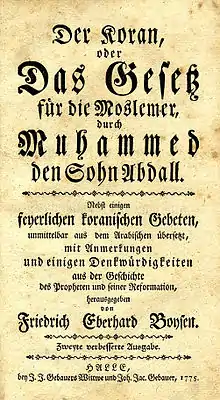

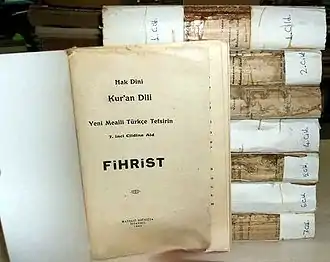

Turkish

The earliest Quranic translation in the Turkish or Turkic language dates back to the 11th century.[50] One of his later translation works is the copy written in the Khorezmian Turkic language in 1363, which is registered in Istanbul's Suleymaniye Library, Hekimoğlu Ali Paşa mosque No:2.[51] This translation in Khorezmian Turkic, like other translations of the Qur'an, is important for language studies. Because the sanctity of the text that is subject to translation will cause the translator to behave more carefully, the errors encountered in the text are not included in such works. Besides, attention was paid to the religious terminology to be understood by the public and that is why Turkic words are given weight.[52] G. Sağol worked on the translation in question.[53] Muhammed Hamdi Yazır worked on tafsir (Qurʻanic exegesis) in the Maturidi context, and published his Hakk Dīni Kur'an Dili, the first Modern Turkish translation of Quran in 1935 by the orders of Kemal Ataturk.

In 1999, the Turkish translation of the Qurʻan, MESAJ by Edip Yüksel was published, about seven years after the publication of his book, Türkçe Kuran Çevirilerindeki Hatalar ("Errors in Turkish Translations of the Qurʻan"). The translation is a Quranist translation, similar to the translation by Yaşar Nuri Öztürk, and does not consider hadith and sectarian traditional jurisprudence as an authority in understanding the Qurʻan. It differs greatly from Sunni and Shia traditions in the translation of numerous crucial words and verses.

Hakkı Yılmaz worked on the Qurʻan through the root meanings of the Arabic words and published a study called Tebyin-ül Qurʻan. And he also published a Division by Division Interpretation in the Order of Revelation.[54]

Hebrew

The translation of the Qur'an to Hebrew by Oz Yona and his staff was published by Goodword books in 2019.[55][56]

Japanese

The first translation into Japanese was done by Sakamoto Ken-ichi in 1920. Sakamoto worked from Rodwell's English translation. Takahashi Goro, Bunpachiro (Ahmad) Ariga and Mizuho Yamaguchi produced Japan's second translation in 1938. The first translation from the Arabic was done by Toshihiko Izutsu in 1945.[57] In 1950, another translation appeared by Shūmei Ōkawa. Other translations have appeared more recently by Ban Yasunari and Osamu Ikeda in 1970 and by Umar Ryoichi Mita in 1972.

Chinese

It is claimed that Yusuf Ma Dexin (1794–1874) is the first translator of the Qurʻan into Chinese. However, the first complete translations into Chinese did not appear until 1927, although Islam had been present in China since the Tang dynasty (618–907). Wang Jingzhai was one of the first Chinese Muslims to translate the Qurʻan. His translation, the Gǔlánjīng yìjiě, appeared in either 1927[58] or 1932, with new revised versions being issued in 1943 and 1946. The translation by Lǐ Tiězhēng, a non-Muslim, was not from the original Arabic, but from John Medows Rodwell's English via Sakamoto Ken-ichi's Japanese. A second non-Muslim translation appeared in 1931, edited by Jī Juémí. Other translations appeared in 1943, by Liú Jǐnbiāo, and 1947, by Yáng Zhòngmíng.[59] The most popular version today is the Gǔlánjīng, translated by Mǎ Jiān, parts of which appeared between 1949 and 1951, with the full edition being published posthumously only in 1981.

Tóng Dàozhāng, a Muslim Chinese American, produced a modern translation, entitled Gǔlánjīng, in 1989. The most recent translation appeared in Taipei in 1996, the Qīngzhēn xīliú – Gǔlánjīng xīnyì, translated by Shěn Xiázhǔn, but it has not found favor with Muslims.[60]

The latest translation 古兰经暨 中文译注 was translated and published by Yunus Chiao Shien Ma in 2016 in Taipei ISBN 978-957-43-3984-6.

Indonesian languages

The Qurʻan has also been translated to Acehnese, Buginese, Gorontalo, Javanese, Sundanese, and Indonesian of Indonesia, the most populous Muslim country in the world. Translation into Acehnese was done by Mahijiddin Yusuf in 1995; into Buginese by Daude Ismaile and Nuh Daeng Manompo in 1982; into Gorontalo by Lukman Katili in 2008; into Javanese by Ngarpah (1913), Kyai Bisyri Mustafa Rembang (1964), and K. H. R. Muhamad Adnan; in Sundanese by A.A. Dallan, H. Qamaruddin Shaleh, Jus Rusamsi in 1965; and in Indonesian at least in three versions: A Dt. Madjoindo, H.M Kasim Bakery, Imam M. Nur Idris, A. Hassan, Mahmud Yunus, H.S. Fachruddin, H., Hamidy (all in the 1960s), Mohammad Diponegoro, Bachtiar Surin (all in the 1970s), and Departemen Agama Republik Indonesia (Indonesian Department of Religious Affair).[61]

Nuclear Malayo-Polynesian languages

William Shellabear (1862–1948) a British scholar and missionary in Malaysia, after translating the Bible into the Malay language began a translation of the Qurʻan, but died in 1948 without finishing it.[62]

Tagalog

In 1982, Abdul Rakman H. Bruce translated the quran in Tagalog which is locally known as "Ang Banal na Kuran".[63]

African languages

- Translation of the Qurʻan to Oromo by Sheikh Mohammed Rashad Abdulle .

- Translation of the Qurʻan to Swahili by Sheikh Ali Muhsin al-Barwani.

- Translation of the Qur'an to Swahili language by Sheikh Said Moosa Mohamed al-Kindy.[64]

- Translation of the Qurʻan to Hausa by Sheikh Muhamud Gumi.

- Translation of the Qurʻan to Yoruba by Sheikh Adam Abdullah Al-Ilory.

- Translation of the Qurʻan to Dagbanli by Sheikh M. Baba Gbetobu.[65]

Esperanto

After the fall of the Shah, Ayatollah Khomeini of Iran called on Muslims to learn Esperanto. Shortly thereafter, an official Esperanto translation of the Qurʻan was produced by the state.

Muztar Abbasi also translated the Qurʻan into Esperanto and wrote a biography of Muhammad and several other books in Esperanto and Urdu.

In 1970, Professor Italo Chiussi, an Ahmadi, translated the Qurʻan into Esperanto.[66]

References

- Fatani, Afnan (2006). "Translation and the Qurʻan". In Leaman, Oliver (ed.). The Qurʻan: an encyclopaedia. Great Britain: Routledge. pp. 657–669.

- Ruthven, Malise (2006). Islam in the World. Granta. p. 90. ISBN 978-1-86207-906-9.

- An-Nawawi, Al-Majmu', (Cairo, Matbacat at-'Tadamun n.d.), 380.

- Christian Høgel, "An early anonymous Greek translation of the Qurʻan. The fragments from Niketas Byzantios' Refutatio and the anonymous Abjuratio", Collectanea Christiana Orientalia 7 (2010), pp. 65–119; Kees Versteegh, "Greek translations of the Qurʻan in Christian polemics (9th century)", Zeitschrift der Deutschen morgenländischen Gesellschaft 141 (1991); Astérios Argyriou, "Perception de l'Islam et traductions du Coran dans le monde byzantin grec", Byzantion 75 (2005).

- Samuel Marinus Zwemer: Translations of the Koran Archived 25 October 2007 at the Wayback Machine, The Moslem World, 1915

- Borrmans, Maurice (2002). "Ludovico Marracci et sa traduction latine du Coran" [Ludovico Marracci and its Latin translation of the Qur'ân]. Islamochristiana (in French) (28): 73–86. INIST:14639389.

- "El català, primera llengua europea a la qual va ser traduït l'Alcorà" (in Catalan). Archived from the original on 28 May 2018. Retrieved 27 May 2018.

- "Коран (Мухаммед; Саблуков)" (in Russian). Retrieved 5 August 2022.

- Arnoud Vrolijk, Sale, George ODNB, 28 May 2015

- Mohammed, Khaleel (1 March 2005). "Assessing English Translations of the Qurʻan". Middle East Quarterly. Archived from the original on 27 June 2017. Retrieved 23 June 2017.

- Appendix ii, (21), Authorized English Translation of the Qurʻan, Rashad Khalifa, Ph.D.

- "God or Allah in Islam (Submission in English), Islam (Submission). Your best source for Islam on the Internet. Happiness is submission to God – Allah, God, Islam, Muslims, Moslems, Arabic, Farsi, Urdu, Indonesia, Arabia, Mecca, USA-Prophet Muhammed's Last S". Archived from the original on 24 July 2011. Retrieved 23 June 2017.

- "God's Messenger of the Covenant, the truth, the covenant, the issues, the proofs, the duties and the Quran.God in Islam (Submission in English),Islam (Submission). Your best source for Islam on the Intenet. Happiness is submission to God-Allah, God, Islam". Archived from the original on 5 August 2008. Retrieved 3 August 2008.

- ″The idol worshipers were destined to tamper with the Qurʻan by adding 2 false verses (9:128–129).″

- Gardner, Martin (1980), Mathematical Games, Scientific American, September 1980, pp16–20.

- The numerology of Dr. Rashad Khalifa – scientist, Martin Gardner, Skeptical Inquirer, Sept–Oct 1997

- Amatul Rahman Omar – The First Woman to Translate the Qurʻan into English Archived 6 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- Hilali-Khan (1999). "Interpretation of the Meanings of The Noble Quran". King Fahd Complex for the Printing of the Holy Quran. Retrieved 16 May 2020.

- Molloy, Rebecca B. (2001). "The Noble Qur'ān: A New Rendering of its Meaning in English, translated by BewleyAbdallhaqq and BewleyAisha. 651 pages, glossary. Norwich, UK: Bookwork, 1999. ISBN 1-874216-36-3". Review of Middle East Studies. 35 (1): 134. doi:10.1017/S0026318400042188. S2CID 191934801. Archived from the original on 20 December 2016. Retrieved 23 June 2017 – via Cambridge Core.

- The Noble Qurʻan: A New Rendering of Its Meaning in English. Bookwork. 23 June 2017. ISBN 978-0-9538639-3-8.

- "The Noble Qurʻan – a New Rendering of its Meaning in English – Diwan Press". www.diwanpress.com. Archived from the original on 1 July 2017. Retrieved 23 June 2017.

- Amatul Rahman Omar, "The Holy Qurʻan – English", The Holy Qurʻan – English, 1990. ISBN 0-9766972-3-8

- Quran (2007). The Sublime Qurʻan: Laleh Bakhtiar: 9781567447507: Amazon.com: Books. ISBN 978-1-56744-750-7.

- Saffarzadeh Commemoration Due Archived 11 May 2012 at the Wayback Machine Iran Daily, 18 October 2010

- Art News in Brief Archived 11 September 2015 at the Wayback Machine Tehran Times, 28 October 2008

- "0192831933 – Oxford University Press, UK – The Qurʻan". Archived from the original on 24 August 2017. Retrieved 23 June 2017.

- The Qurʻan. OUP Oxford. 17 April 2008. ASIN 0199535957.

- "A new look at a holy text – tribunedigital-chicagotribune". Articles.chicagotribune.com. 10 April 2007. Archived from the original on 18 May 2015. Retrieved 10 May 2015.

- Useem, Andrea (18 April 2007). "Laleh Bakhtiar: An American Woman Translates the Qurʻan". Publishersweekly.com. Retrieved 10 May 2015.

- Aslan, Reza (20 November 2008). "How To Read the Qurʻan". Slate. Archived from the original on 28 July 2011. Retrieved 8 July 2011.

- "In Maulana Wahiduddin Khan, India loses an advocate of inter-religious harmony to Covid-19". ThePrint. 22 April 2021. Retrieved 23 February 2022.

- "Maulana Wahiuddin Khan, Islamic Scholar, Dies Of COVID-19". NDTV.com. Retrieved 23 February 2022.

- "The Clear Quran: Siraj Publications". Archived from the original on 7 March 2016. Retrieved 2 March 2016.

- "Qurʻan in English – Division by Division English Interpretation of the Qurʻan in the Order of Revelation". www.quraninenglish.net. Archived from the original on 9 January 2019. Retrieved 18 January 2019.

- "The Majestic Qurʻan". Archived from the original on 21 June 2018. Retrieved 18 January 2019.

- https://tahapublishers.com/book/the-easy-quran

- "The Quran Beheld: An English Translation from the Arabic English text and Appendices by NUH HA MIM KELLER (transl.)". Journal of Islamic Studies. Retrieved 29 April 2023.

- "Mafhoom'ul Quran" (PDF). Tolueislam.com. Retrieved 23 December 2013.

- "In Maulana Wahiduddin Khan, India loses an advocate of inter-religious harmony to Covid-19". ThePrint. 22 April 2021. Retrieved 23 February 2022.

- Service, Tribune News. "Maulana Wahiduddin Khan: He lived in faith and forgiveness". Tribuneindia News Service. Retrieved 23 February 2022.

- Bureau, Minhaj Internet. "Urdu Qurʻan اردو قرآن - عرفان القرآن : قرآنِ مجید کا عام فہم اور جدید ترین پہلا آن لائن يونيکوڈ اُردو ترجمہ - Irfan-ul-Qurʻan, Read Listen Search Download & Buy". www.irfan-ul-quran.com. Archived from the original on 29 June 2017. Retrieved 23 June 2017.

- "MY QURAN PAK". sites.google.com. Archived from the original on 17 September 2016. Retrieved 23 June 2017.

- বাংলা ভাষায় কোরআন অনুবাদের ধারাক্রম. Kaler Kantho (in Bengali). 25 July 2019.

- Dey, Amit (7 June 2012). "Bengali Translation of the Quran and the Impact of Print Culture on Muslim Society in the Nineteenth Century" (PDF). University of Calcutta, Department of History: 8–18. Retrieved 24 January 2016.

- Hafez Ahmed. "Al Qurʻan Academy to observe 200 years of translating Holy Qurʻan into Bengali". Archived from the original on 4 November 2013. Retrieved 23 June 2017.

- Sazzadur Rahman, Chayanir Publication, Tangail, Bangladesh

- Zayed, Tareq M. (1 January 1970). "The Role Of Reading Motivation And Interest In Reading Engagement Of Qurʻanic Exegesis Readers | Tareq M Zayed". Academia.edu. Retrieved 23 June 2017.

- "Arabic and Bengali". Calcutta Gazette. Alipore, Bengal: Bengal Government Press. October–December 1939. p. 94.

- Kalamu Rahman | Barkati Publishers; By Sayyad Aale Rasool Hasnain Miya Nazmi. 30 September 2015.

- A. İnan, Kuran-ı Kerim’in Türkçe Tercümeleri Üzerinde Bir İnceleme, Ankara 1961, s.8.

- J. Eckmann, “Eastern Turkic Translations of the Koran”, Studia Turcica, Budapest 1971, s. 155.

- A. Erdoğan, “Kur’an tercemelerinin Dil Bakımından Değerleri”, Vakıflar Dergisi, 1 (1969), s. 47-51.

- An Interlinear Translatıon of the Qur’an Into Khwarazm Turkish, I. Introduction-Text, Turkish Sources XIX, Harvard University 1993, XL+369[2]s.; II. Glossary, Harvard University 1993; III. Facsimile, Harvard University 1996.

- "Hakkı Yılmaz – İşte Kuran". www.istekuran.net. Archived from the original on 25 March 2018. Retrieved 18 January 2019.

- "Hebrew". www.cpsquran.com. Retrieved 22 August 2020.

- "Hebrew-Quran".

- "The Qu'ran and its translators". Archived from the original on 21 June 2012.

- Clinton Bennett, The Bloomsbury Companion to Islamic Studies, pg. 298. London: A & C Black, 2013. ISBN 9781441127884

- Lynn, Aliya Ma (2007). Muslims in China. University of Indianapolis Press. p. 29. ISBN 978-0-88093-861-7.

- ""Chinese Translations of the Qur'ān: a Close Reading of Selected Passages", by Ivo Spira, MA thesis, Oslo University, 2005" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 September 2012.

- "Al-Quran Dan Terjemahnya" (PDF). Alagr.com. Archived (PDF) from the original on 7 July 2011. Retrieved 23 June 2017.

- Hunt, Robert (2002). "The Legacy of William Shellabear". International Bulletin of Missionary Research. 26 (1): 28–31. doi:10.1177/239693930202600108. S2CID 151333563. Archived from the original on 2 July 2013.

- Abdul Rakman Bruce. "Ang Banal na Kuran". Archived from the original on 22 August 2018. Retrieved 14 January 2019.

- title: asili ya uongofu

- "First Dagbani Version of Holy Quran Launched". GhanaWeb. 19 December 2008. Archived from the original on 27 September 2016. Retrieved 25 September 2016.

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 21 March 2016.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

Further reading

- Ali, Muhammad Mohar (2004). The Qurʻan and the Orientalists. Jamiat Ihyaa Minhaaj al-Sunnah (JIMAS), Ipswich, United Kingdom. ISBN 0954036972.

- Tibawi, A. L. (1962). "Is the Qur'ān Translatable?". The Muslim World. 52 (1): 4–16. doi:10.1111/j.1478-1913.1962.tb02588.x.

- Pearson, J.D., ‟Bibliography of Translations of the Qur'ān into European Languages", in: A.F.L. Beeston et al. (eds), Arabic Literature to the End of the Umayyad Period (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1983), pp. 502–520.

- Wilson, M. Brett (2009). "The First Translations of the Qurʾan in Modern Turkey (1924–38)". International Journal of Middle East Studies. 41 (3): 419–35. doi:10.1017/S0020743809091132. S2CID 73683493.

- Bein, Amit (2011). Ottoman Ulema, Turkish Republic Agents of Change and Guardians of Tradition. Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8047-7311-9.

- Fitzpatrick, Coeli; Walker, Adam (2014). Muhammad in History, Thought, and Culture An Encyclopedia of the Prophet of God. Abc-Clio Incorporated. pp. 510–512. ISBN 978-1-61069-177-2.