Rückert-Lieder

The Rückert-Lieder (Songs after Rückert) is a collection of five Lieder for voice and orchestra or piano by Gustav Mahler, based on poems written by Friedrich Rückert. Four of the songs ("Blicke mir nicht in die Lieder!", "Ich atmet’ einen linden Duft", "Ich bin der Welt abhanden gekommen", and "Um Mitternacht") were written in the summer of 1901 at Maiernigg, with one ("Liebst du um Schönheit") completed in the summer of 1902, also in Maiernigg. Both smaller in orchestration and briefer than Mahler's previous Der Knaben Wunderhorn settings, the collection marked a change of style from the childlike, often satirical Wunderhorn settings, to a more lyrical, contrapuntal style. The collection is often linked with the Kindertotenlieder, Mahler's other settings of Rückert's poetry, and with the 5th Symphony, and both were composed concurrently with the collection and contain subtle references to the Rückert-Lieder.

| Rückert-Lieder | |

|---|---|

| Song cycle by Gustav Mahler | |

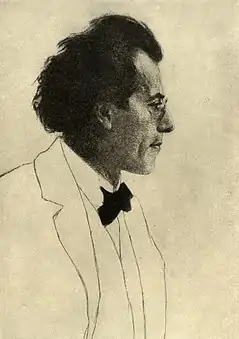

The composer, portrayed by Emil Orlik, c. 1903 | |

| Text | poems by Friedrich Rückert |

| Language | German |

| Composed | 1901–02 |

| Performed | 29 January 1905 |

| Published | 1905, 1910 |

| Movements | five |

| Scoring |

|

| Audio sample | |

"Ich bin der Welt abhanden gekommen", performed by the U.S. Navy Band

| |

The Rückert-Lieder (without "Liebst du um Schönheit") were premiered, alongside the Kindertotenlieder and several Wunderhorn settings, in Vienna on 29 January 1905 by Mahler and members of the Vienna Philharmonic, sung by Anton Moser and Friedrich Weidemann. The songs met with a positive reception, though they were overshadowed by the Kindertotenlieder and the Wunderhorn settings which were performed, along with the Rückert-Lieder, in a repeat performance on 3 February 1905. The songs were first published as a collection in their versions for piano accompaniment in 1905, and later re-published, in full score, along with the Der Knaben Wunderhorn settings of "Revelge" and "Der Tamboursg’sell" in Sieben Lieder aus letzter Zeit (Seven Songs of Latter Days) in 1910.

The Rückert-Lieder, along with the Kindertotenlieder and the 5th Symphony, are considered to be a turning point in Mahler's oeuvre, and many elements of these songs would anticipate later works such as Das Lied von der Erde.

History

Composition

In 1897, Mahler became the director of the Vienna Hofoper. Over the following years his compositional output dwindled due to over-work and ill health; between 1897 and 1900, he only completed the Fourth Symphony and the Der Knaben Wunderhorn setting ‘Revelge’.[1] Eventually Mahler suffered a near-fatal haemorrhage on the night of February 24, 1901, requiring emergency treatment, an operation, and a seven week long recuperation.[2]

From June to August 1901, Mahler spent his vacation at his newly completed lakeside villa near Maiernigg. Its isolation meant the summer was peaceful,[3] and he experienced the most productive summer of his life,[4] completing two movements of the Fifth Symphony and eight Lieder, including four of the Rückert-Lieder.[1] By 10 August, Mahler was playing six of his Rückert settings (including three of the Kindertotenlieder) plus "Der Tamboursg’sell" to Natalie Bauer-Lechner, and according to her chronicles, each song was composed in one day and orchestrated the next day.[5] Then on 16 August, "Ich bin der Welt abhanden gekommen" was completed.[4][6] The serenity of his surroundings, as well as the emotional aftereffects of the near-death experienced he had suffered earlier in 1901 (seen most in "Um Mitternacht")[7] exerted a considerable influence on the Rückert-Lieder, and they contributed to Mahler creating a new musical style which has been said to “[reveal] an artist who is already exploring another world”.[1][8]

The next year, after his courtship and marriage to Alma Schindler, Mahler composed another Rückert setting that was eventually added to the collection: "Liebst du um Schönheit". Unlike the other four, this was solely intended as a private gift to Alma as a proof of his love for her, due to simmering tensions between her and Mahler at the time. On 10 August, Mahler presented the song to Alma, who was deeply moved by the setting of the last line: Liebe mich immer, dich lieb' ich immer, immerdar.[9] Due to its intimate nature, Mahler never orchestrated the song,[10] and it was not performed in public in Mahler's lifetime.[11] Instead, when the full collection was published, it was orchestrated by Max Pullman, an editor at the publishing company C. F. Kahnt, who first published these Lieder.[12][11]

Premiere and initial reception

Four of the Rückert-Lieder ("Liebst du um Schonheit" was not included in the programme) were premiered, alongside the five Kindertotenlieder, and six of the Wunderhorn settings, on 29 January 1905 in Vienna at the small Musikvereinsaal, now called the Brahmssaal.[13] The singers were the tenor Fritz Schrödter and the baritones Friedrich Weidemann and Anton Moser. These singers were accompanied by members of the Vienna Philharmonic, which were conducted by Mahler himself.[13] Moser sang "Ich atmet’ einen linden Duft!" and "Blicke mir nicht in die Lieder!", and Weidemann sang "Ich bin der Welt abhanden gekommen" and "Um Mitternacht".[13] The songs were in the following order:

- Ich atmet’ einen linden Duft!

- Blicke mir nicht in die Lieder!

- Ich bin der Welt abhanden gekommen'

- Um Mitternacht[14]

The concerts were part of a series of concerts organised by the Vereinigung schaffender Tonkünstler in Wien, founded on 23 April 1904 by Arnold Schoenberg and Alexander von Zemlinsky (among others).[15] Mahler had accepted the honorary presidency of the Vereinigung,[16] and he helped to organise and perform in several of these concerts,[17] of which this Lieder concert was one. Mahler had already promised Schoenberg and Zemlinsky when he accepted the honorary presidency that he would premiere one of his own works for the Vereinigung.[18] Mahler could not premiere the 5th Symphony, as it would be too costly to perform, and in any case had already been promised to Fritz Steinbach's Gürzenich Orchestra in Cologne.[18] Instead, Mahler opted to complete the Kindertotenlieder in the summer of 1904, and premiere that song cycle and the Rückert-Lieder in a Lieder concert, which was especially interesting given that most of Mahler's Lieder with orchestral accompaniment had not been performed yet.[18]

Due to demand, the final rehearsal (on 28 January, the day before the premiere) was open to the public, and the concert itself was completely sold out, with many being turned away at the door.[13] The concert was greeted with a positive reception, with Paul Stefan writing that "Mahler's Lieder touched everyone".[19] Anton Webern, who attended the premiere, was more cool, writing in his diary that the Rückert-Lieder were "less satisfactory" and even "sentimental", but still containing a "beauty of vocal expression, which is sometimes of overwhelming inwardness", singling out "Ich atmet einen linden Duft" for praise.[20] David Josef Bach noted that "With [Mahler], words do not create the atmosphere. It is more as if, in order to create it, he needs the text as much as the music".[21] Julius Korngold thought that Mahler's setting of Rückert's poetry was "noble, sensitive and poetic", though he felt that the intimacy of Rückert's poetry was not well suited to orchestral accompaniment.[21] Finally, an anonymous critic wrote:

The songs, their sequence, and their performance offered the highest state of polished refinement ... It does not matter to [Mahler] or to the listeners whether the melodies are suffused with juicy banalities or borrowed from Bruckner's Romantic [Symphony] ... He makes the accompaniment progress in the time-honoured manner, stepwise with the voice, but casts over the whole a glittering orchestral web, full of clever ideas and piquant effects.[22]

The programme was repeated in another sold-out concert[23] on February 3rd, this time with Marie Gutheil-Schoder singing three additional Wunderhorn settings.[24] Following the concert, Mahler had dinner with the musicians of the Vereinigung, which deepened the bond between the two.[24] Webern later recalled that Mahler had said that "After Des Knaben Wunderhorn I could only compose more Rückert – which is lyricism at first hand, all the rest is lyricism at second hand."[24] More importantly for Mahler, these two triumphant performances had made him become aware that he had entered a new period in his career as a composer.[25] As for the Vereinigung, the long rehearsals for the concert had been costly, as it was necessary to pay overtime to the Philharmonic musicians,[23] on top of their already considerable fee to perform in the first place.[26] Despite being sold out twice, the small Musikvereinsaal had not enough seats to cover expenses,[23] which forced the Vereinigung to cancel an orchestral concert, and to finally cease activities after two final chamber music concerts on February 20th and April 17th.[25]

Later in 1905, C. F. Kahnt would publish the Rückert-Lieder with their piano accompaniment.[27] It would take until 1908 for Kahnt to agree publication the full scores of those songs with orchestral accompaniments,[28] and 1910 for these scores to appear, along with Mahler's settings of 'Revelge' and 'Der Tamboursg’sell' from Der Knaben Wunderhorn in Sieben Lieder aus letzter Zeit (Seven Songs of Latter Days) in 1910. Universal Edition later published a score consisting of only the five Rückert settings.

Subsequent performances and reception

Mahler subsequently performed two of the Rückert-Lieder, namely 'Ich bin der Welt abhanden gekommen', sung by Weidemann,[29] and 'Um Mitternacht', sung by Erik Schmedes,[14][29] in a concert at the Graz Festival, on June 1st, 1905.[14][30] Mahler again conducted, with the orchestra comprising 23 members of the Konzertverin Orchestra and "professors from the Steiermäkischer Muisverein,"[30] as well as members of the Vienna Philharmonic that accompanied Mahler to Graz.[31] The acclaim from the audience was apparently so spontaneous that the fellow composers in the hall, as well as those who regularly criticised Mahler, booed him off in envy.[32] Again critics, even those who were biased against Mahler's work, praised this triumph,[33] with Ernst Decsey saying "Each song was incontestably a 'phenomenon' unto itself, because of the 'absolutely unprecedented [sonority] of his chamber orchestra."[34] These reports paved the way for the Neue Zeitschrift für Musik to publish a long article about Mahler's Lieder later in 1905.[35] In 1911, the Grazer Volksblatt, reminiscing on the concert in the wake of Mahler's death, would write that "few eyes remained dry in the concert hall" and that "the audience surrounded [Mahler] with acclamation, ... gratitude, and genuine love."[32]

On February 14, 1907, Mahler accompanied Johannes Messchaert at the piano[36] in a recital at the Bösendorfer Saal in Berlin,[37] consisting of five early Wunderhorn settings, the Lieder eines fahrenden Gesellen, the Kindertotenlieder, and the same four Rückert-Lieder as at the collection's premiere.[37] An unsigned article in the Vossiche Zeitung wrote that there had been a "sizeable audience", alluded to the Graz concert, and said the Rückert-Lieder were "certainly among the best songs that Mahler had composed".[38] Paul Bekker in the Allgemeine Musik-Zeitung again repeated the criticism that the songs were occasionally "sentimental."[39] Otto Klemperer later recalled that the concert was "wonderfully compelling" and "quite unbelievable."[37] Messchaert and Mahler would later perform two of the Rückert-Lieder at a concert in Cologne on July 1st, again to acclaim.[40]

Overview

The Rückert-Lieder consist of the following songs:

- "Blicke mir nicht in die Lieder!" (Do not look at my songs)[41] – June–July 1901[42]

- "Ich atmet’ einen linden Duft!" (I breathed a delicate fragrance)[43] – June–July 1901[44]

- "Ich bin der Welt abhanden gekommen" (I am lost to the world)[45] – 16 August 1901[46]

- "Um Mitternacht" (At midnight)[47] – June–July 1901[48]

- "Liebst du um Schönheit" (If you love for beauty)[49] – August 1902[50]

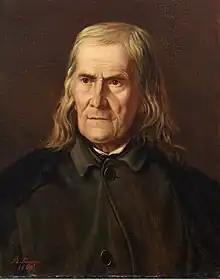

The Rückert-Lieder are all settings of poems by the early 19th-century poet Friedrich Rückert. Rückert's poems are heavily influenced by his activity as a scholar of Oriental languages,[51][52] and his poems were widely read in his lifetime, being set by composers such as Robert Schumann and Franz Schubert.[53] Between 1895 and 1900 his poetry revived in popularity, but today he is generally considered a minor poet, though Mahler was not troubled by this, holding the view that masterpieces of poetry should not be set to music.[53]

The turn to Rückert's poetry has been considered conservative on Mahler's part, given his connections with modernists such as Richard Strauss,[54] the musicians of the Vereinigung,[55] and the artists of the Vienna Secession,[56][57] as well as the novelty of his own music.[54] However, Mahler himself felt no need to borrow from these early modernist trends of which he was aware.[54] Furthermore, Henry Louis de la Grange posits that Mahler was attracted to the lyricism of Rückert's poetry, and points out both of them "admired folk-art" and considered it the "living source of all poetry".[58] In addition, Rückert has also been considered a "close spiritual relative" to Gustav Fechner, an Orientalist and psychophysicist who was greatly admired by Mahler.[52][59] Mahler himself drew comparisons between the two.[60] Stephen E. Hefling has also suggested that Mahler, disappointed by the lack of popularity of his Wunderhorn settings, was drawn to setting more popular poetry in order to appeal to a wider audience, provided it met his artistic purposes.[60]

The songs exist in versions for piano and orchestral accompaniment; Mahler composed both versions simultaneously and performed the Lieder in both versions. Thus, the piano version is regarded to be as authoritative as the orchestral version.[14]

The Rückert-Lieder were never intended to be a cohesive song-cycle. The piano score and the orchestral score differ in their ordering of the songs, and when conducting the songs, Mahler frequently changed the order of the songs according to the circumstances of each performance.[14] For example, at the premiere performance on January 29th, 1905, the songs were in the following order:

- Ich atmet’ einen linden Duft!

- Blicke mir nicht in die Lieder!

- Ich bin der Welt abhanden gekommen'

- Um Mitternacht

But at the repeat performance on 3 February, the songs were in the following order:

- Ich bin der Welt abhanden gekommen

- Blicke mir nicht in die Lieder!

- Ich atmet’ einen linden Duft!

- Um Mitternacht

In addition, each of the songs requires a specific ensemble of instruments, different from one song to the next,[14] though the instrumentation of all five combined is equivalent to a standard-sized orchestra.[58] Though it has become standard to perform them in large halls with full-size orchestras, Mahler himself premiered and preferred to perform the Rückert-Lieder in a small hall with a small orchestra,[14] particularly cutting down the size of the string section.[61] The scoring of the Lieder often focus on small groups of instruments akin to chamber music, with even the voice being treated like an instrument.[62][63]

It is generally considered that Mahler forged a new style with this collection. Not only did he abandon setting the poems from Der Knaben Wunderhorn (with the exceptions of "Revelge" and "Der Tamboursg’sell"), but he also started writing exclusively instrumental symphonies, without explicit references to his songs. Instead of the "ironic, critical stance" assumed in the Wunderhorn settings, Mahler instead adopts a "first-person perspective that ... is intimately introspective."[64] Donald Mitchell writes of the songs:

Gone are the fanfares, the military signals, the dance and march rhythms and the quasi-folk style of the Wunderhorn songs. Gone too are those songs' satirical excursions, with their accompanying instrumental pungencies and sarcasms.[65]

Instead, the collection, with its "brevity and intimate character ... represent[s] a short interlude of pure lyricism in [Mahler's] work,"[66] characterised by linear counterpoint[67] and heterophony.[68] This focus on melody, as well as the transparent, chamber-like orchestration and briefness of the songs, contribute to their lyrical nature.[69] Despite this lyricism, and the serene circumstances that Mahler experienced when he composed these songs, the songs sometimes take on darker tones.[70] For example, 'Um Mitternacht' deals with metaphysical questions that preoccupied Mahler,[53] and both that song and 'Ich bin der Welt' deal with man's loneliness in the world.[69] The latter song in its spiritual withdrawal from the world has been said to be influenced by Buddhist thought and the philosophy of Arthur Schopenhauer,[10] who Mahler was heavily influenced by.[71]

The collection has been viewed as representing the "supreme consummation and perfection of the Mahler Lied,"[66] and as anticipating the style, not only of his 5th, 6th, and 7th symphonies, but also of his late works, such as Das Lied von der Erde and the 9th Symphony.[72]

Instrumentation

The instrumentation of the complete collection is as follows:

|

|

| "Blicke mir nicht ..." | "Ich atmet' einen linden ..." | "Ich bin der Welt ..." | "Um Mitternacht" | "Liebst du um Schönheit" |

| Flute | Flute | 2 Flutes | ||

| Oboe | Oboe | Oboe | Oboe d'amore | 2 Oboes |

| English horn | English horn | |||

| Clarinet (B♭) | Clarinet (A) | 2 Clarinets (B♭) | 2 Clarinets (A) | 2 Clarinets (B♭) |

| Bassoon | 2 Bassoons | 2 Bassoons | 2 Bassoons | 2 Bassoons |

| Contrabassoon | ||||

| Horn (F) | 3 Horns (F) | 2 Horns (E♭) | 4 Horns (E♭) | 4 Horns (F) |

| 2 Trumpets (E♭) | ||||

| 3 Trombones | ||||

| Bass tuba | ||||

| Timpani | ||||

| Celesta | ||||

| Harp | Harp | Harp | Harp | Harp |

| Piano | ||||

| Violin I | Violin | Violin I | Violin I | |

| Violin II | Violin II | Violin II | ||

| Viola | Viola | Viola | Viola | |

| Cello | Cello | Cello | ||

| Contrabass | Contrabass |

Discography

- Frederica von Stade – Mahler Songs, London Philharmonic Orchestra, conducted by Andrew Davis, Columbia, 1979

References

- Franklin (2001), §7 "Vienna 1897–1907"

- de la Grange (1995), pp. 334, 342.

- de la Grange (1995), p. 365.

- de la Grange (1995), p. 369.

- Hefling (1999), p. 344.

- Mitchell (2002), p. 122.

- Hefling (2007), p. 110.

- de la Grange (1995), pp. 367–368.

- de la Grange (1995), p. 538.

- Hefling (2007), p. 111.

- de la Grange (1995), p. 797.

- Kennedy, Michael (1990). The Master Musicians: Mahler (2nd ed.). London: J. M. Dent & Sons. p. 135. ISBN 978-0-460-12598-7.

- de la Grange (1999), p. 107.

- de la Grange (1995), p. 786.

- de la Grange (1995), p. 687.

- de la Grange (1995), p. 689.

- de la Grange (1995), pp. 692–693.

- de la Grange (1995), p. 710.

- de la Grange (1999), pp. 107–108.

- de la Grange (1999), p. 108.

- de la Grange (1999), p. 118.

- de la Grange (1999), p. 117.

- de la Grange (1999), p. 124.

- de la Grange (1999), p. 110.

- de la Grange (1999), p. 125.

- de la Grange (1995), p. 693.

- de la Grange (1999), p. 62.

- de la Grange, Henry-Louis (2008). Gustav Mahler: A New Life Cut Short (1907–1911). Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 278. ISBN 978-0-19-816387-9.

- de la Grange (1999), p. 218.

- de la Grange (1999), p. 213.

- de la Grange (1999), p. 216.

- de la Grange (1999), p. 219.

- de la Grange (1999), pp. 220–222.

- de la Grange (1999), p. 220.

- de la Grange (1999), pp. 223–224.

- de la Grange (1999), p. 601.

- de la Grange (1999), p. 603.

- de la Grange (1999), pp. 603–4.

- de la Grange (1999), p. 604.

- de la Grange (1999), p. 665.

- Mitchell (2002), pp. 36–37.

- de la Grange (1995), p. 787.

- Mitchell (2002), pp. 30–31.

- de la Grange (1995), p. 788.

- Mitchell (2002), pp. 32–33.

- de la Grange (1995), p. 791.

- Mitchell (2002), pp. 34–35.

- de la Grange (1995), p. 793.

- Mitchell (2002), pp. 38–39.

- de la Grange (1995), p. 796.

- de la Grange (1995), pp. 782–783.

- Mitchell (2002), p. 128.

- de la Grange (1995), p. 782.

- McCoy (2021), p. 148.

- de la Grange (1995), pp. 689–694.

- Pippal (2021), pp. 143–145.

- Franklin (2001), §12 "Fifth and Sixth Symphonies, Rückert settings".

- de la Grange (1995), p. 783.

- Barham (2021), p. 210.

- Hefling (1999), p. 342.

- Hefling (1999), p. 343.

- de la Grange (1995), pp. 783–784.

- Mitchell (2002), p. 60.

- Hefling (1999), p. 339.

- Mitchell (2002), p. 68.

- de la Grange (1995), p. 781.

- Mitchell (2002), pp. 59–60.

- Mitchell (2002), pp. 62–64.

- de la Grange (1995), p. 784.

- de la Grange (1995), pp. 781–782.

- Solvik (2021), pp. 186–187.

- Mitchell (2002), pp. 56.

Sources

- Barham, Jeremy. "Literary Enthusiasms". In Youmans (2021).

- de la Grange, Henry-Louis (1995). Gustav Mahler: Vienna: The Years of Challenge (1897–1904). Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-315159-8.

- de la Grange, Henry-Louis (1999). Gustav Mahler: Vienna: Triumph and Disillusion (1904–1907). Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-315160-4.

- Franklin, Peter (2001). "Mahler, Gustav". Grove Music Online (8th ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.article.40696. ISBN 978-1-56159-263-0.

- Hefling, Stephen E. (1999). "The Rückert Lieder". In Mitchell, Donald; Nicholson, Andrew (eds.). The Mahler Companion. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 342. ISBN 978-0-19-816376-3.

- Hefling, Stephen E. (2007). "Song and symphony (II). From Wunderhorn to Rückert and the middle-period symphonies: vocal and instrumental works for a new century". In Barham, Jeremy (ed.). The Cambridge Companion to Mahler. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 110. ISBN 978-1-139-00169-4.

- McCoy, Marilyn L. "Mahler and Modernism". In Youmans (2021).

- Mitchell, Donald (2002) [1985, Faber & Faber, London]. Gustav Mahler, Songs and Symphonies of Life and Death: Interpretations and Annotations. Woodbridge: The Boydell Press. ISBN 978-0-85-115908-9.

- Pippal, Martina. "Mahler and the Visual Arts of His Time". In Youmans (2021), pp. 143–145.

- Solvik, Morten. "German Idealism". In Youmans (2021).

- Youmans, Charles, ed. (2021). Mahler in Context. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-108-43835-3.

External links

- Rückert Lieder: Scores at the International Music Score Library Project

- Fünf Rückertlieder, the lyrics with translations at the LiederNet Archive

- Rückertlieder Chronologie Discographie Commentaires on gustavmahler.net (in French)