R101

R101 was one of a pair of British rigid airships completed in 1929 as part of the Imperial Airship Scheme, a British government programme to develop civil airships capable of service on long-distance routes within the British Empire. It was designed and built by an Air Ministry–appointed team and was effectively in competition with the government-funded but privately designed and built R100. When built, it was the world's largest flying craft[3] at 731 ft (223 m) in length, and it was not surpassed by another hydrogen-filled rigid airship until the LZ 129 Hindenburg was launched seven years later.

| R101 | |

|---|---|

R101 on the day of its first flight, 14 October 1929. | |

| General information | |

| Role | Experimental airship |

| Manufacturer | Royal Airship Works |

| Designer | |

| Number built | 1 |

| History | |

| First flight | 14 October 1929[1] |

| Last flight | 4 October 1930[2] |

| Fate | Crashed and burnt out 5 October 1930 |

After trial flights and subsequent modifications to increase lifting capacity, which included lengthening the ship by 46 ft (14 m) to add another gasbag,[4] the R101 crashed in France during its maiden overseas voyage on 5 October 1930, killing 48 of the 54 people on board.[5] Among the passengers killed were Lord Thomson, the Air Minister who had initiated the programme, senior government officials, and almost all the dirigible's designers from the Royal Airship Works.

The crash of R101 effectively ended British airship development, and was one of the worst airship accidents of the 1930s. The loss of 48 lives was more than the 36 killed in the much better-known Hindenburg disaster of 1937, though fewer than the 52 killed in the French military Dixmude in 1923 and the 73 killed when the USS Akron crashed in the Atlantic Ocean off the coast of New Jersey in 1933.

Background

R101 was built as part of a British government initiative to develop airships to provide passenger and mail transport from Britain to the most distant parts of the British Empire, including India, Australia and Canada, since the distances were then too great for heavier-than-air aircraft. The Burney Scheme of 1922 had proposed a civil airship development programme to be carried out by a specially-established subsidiary of Vickers with the support of the British government. The scheme drew support from the Air Ministry, which sought more airships and a base in India. The Admiralty added that it would forgo some light cruisers of which it was very short. However, Prime Minister Lloyd George's government decided it could not afford to support the Burney Scheme.[6]

When the 1923 general election brought Ramsay MacDonald’s Labour administration to power, the new Air Minister, Lord Thomson, formulated the Imperial Airship Scheme in place of the Burney Scheme.[7] It called for the building of two experimental airships: one, R101, to be designed and constructed under the direction of the Air Ministry, and the other, R100, to be built by a Vickers subsidiary, the Airship Guarantee Company, under a fixed-price contract. They were nicknamed the "Socialist Airship" and the "Capitalist Airship", respectively.[8]

In addition to the building of the two airships, the Imperial Airship Scheme involved the establishment of the necessary infrastructure for airship operations; for example, the mooring masts used at Cardington, Ismalia, Karachi and Montreal had to be designed and built, and the meteorological forecasting network extended and improved.[9]

Specifications for the airships were drawn up by an Air Ministry committee, whose members included Squadron Leader Reginald Colmore and Lieutenant-Colonel V.C. Richmond,[10] both of whom had extensive experience with airships, most of them non-rigid. They called for airships of not less than five million cubic feet (140,000 m³) capacity and a fixed structural weight not to exceed 90 tons, giving a "disposable lift" of nearly 62 tons. With the necessary allowance of about 20 tons for the service load consisting of a crew of approximately 40, as well as stores and water ballast, this allowed a possible fuel and passenger load of 42 tons. Accommodation for 100 passengers and tankage for 57 hours' flight was to be provided, and a sustainable cruise speed of 63 mph (101 km/h) and maximum speed of 70 mph (110 km/h) were called for.[11] In wartime, the airships would be expected to carry 200 troops or possibly five parasite fighter aircraft.

Vickers' design team was led by Barnes Wallis, who had extensive experience of rigid airship design and later became famous for the geodetic framework of the Wellington bomber and for the bouncing bomb. His principal assistant (the "Chief Calculator"), Nevil Shute Norway, later well known as the novelist Nevil Shute, later gave his account of the design and construction of the two airships in his 1954 autobiography, Slide Rule: Autobiography of an Engineer. Shute Norway's book characterises R100 as a pragmatic and conservative design, and R101 as extravagant and overambitious, but one purpose of having two design teams was to test different approaches, with R101 deliberately intended to extend the limits of existing technology.[12] Shute Norway later admitted that many of his criticisms of the R101 team were unjustified.[13]

An extremely-optimistic timetable was drawn up, with construction of the government-built R101 to begin in July 1925 and be complete by the following July, with a trial flight to India planned for January 1927.[14] In the event, the extensive experimentation that was necessary delayed the start of construction of R101 until early 1927. R100 was also delayed, and neither flew until late 1929.

Design and development

The entire airship programme was under the direction of the Director of Airship Development (DAD), Group Captain Peregrine Fellowes, with Colmore acting as his deputy. Lieutenant-Colonel Richmond was appointed Director of Design: later he was credited as "Assistant Director of Airship Development (Technical)"[15] with Squadron Leader Michael Rope as his assistant. The Director for Flying and Training, responsible for all operational matters for both airships, was Major G.H. Scott, who had developed the design of the mooring masts that were to be built. Work was based at the Royal Airship Works at Cardington, Bedfordshire, which had been built by Short Brothers during the First World War and had been employed by the Admiralty to copy and improve on the latest German designs from captured rigid airships. The Works had been nationalised in 1919, but after the loss of the R38 (then in the process of being transferred to the US as ZR2), naval airship development was stopped and it had been placed on a care and maintenance basis.

R101 was to be built only after completion of an extensive research and test programme by the National Physical Laboratory (NPL). As part of this programme, the Air Ministry funded the costs of refurbishing and flying R33 in order to gather data about structural loads and the airflow around a large airship.[11] This data was also made available to Vickers;[16] both airships had the same elongated tear-drop shape, unlike previous designs. Hilda Lyon, who was responsible for the aerodynamic development, found that this shape produced the minimum amount of drag.[17][18] Safety was a primary concern and this would have an important influence on the choice of engines.

An early decision had been made to construct the primary structure largely from stainless steel rather than lightweight alloys such as duralumin. The design of the primary structure was shared between Cardington and the aircraft manufacturer Boulton and Paul, who had extensive experience in the use of steel and had developed innovative techniques for forming steel strip into structural sections. Working to an outline design prepared with the help of data supplied by the NPL, the stress calculations were performed by Cardington. This information was then supplied to J.D. North and his team at Boulton and Paul, who designed the metalwork.[19] The individual girders were fabricated by Boulton and Paul in Norwich, and transported to Cardington where they were bolted together. This scheme for a prefabricated structure entailed demanding manufacturing tolerances and was entirely successful, as the ease with which R101 was eventually extended bears witness. Before any contracts for the metalwork were signed, an entire bay consisting of a pair of the 15-sided transverse ring frames and the connecting longitudinal girders was assembled at Cardington. After the assembly had passed loading tests, the individual girders were then tested to destruction. The structure of the airframe was innovative: the ring-shaped transverse frames of previous airships had been braced by radial wires meeting at a central hub, but no such bracing was used in R101, the frames being stiff enough in themselves.[20] However, this resulted in the structure extending further into the envelope, thereby limiting the size of the gasbags.

The specifications drawn up in 1924 by the Committee for the Safety of Airships had based weight estimates on the then-existing rules for airframe strengths. However, the Air Ministry Inspectorate introduced a new set of rules for airship safety standards in late 1924 and compliance with these as-yet unformulated rules had been explicitly mentioned in the individual specifications for each airship.[21] These new rules called for all lifting loads to be transmitted directly to the transverse frames rather than being taken via the longitudinal girders.[22] The intention behind this ruling was to enable the stressing of the framework to be fully calculated, rather than relying on empirically accumulated data, as was contemporary practice at the Zeppelin design office. Apart from the implications for the airframe weight, one effect of these regulations was to force both teams to contrive a new system of harnessing the gasbags. R101's patented "parachute" gasbag harnessing, designed by Michael Rope, proved less than satisfactory, permitting the bags to surge unduly, particularly in rough weather.[23] This caused the gasbags to chafe against the structure, tearing holes in the fabric. Another effect was that both R100 and R101 had a relatively small number of longitudinal girders in order to simplify the stress calculations.

R101 used pre-doped linen panels for much of its covering, rather than lacing undoped fabric into place and then applying dope to shrink it. In order to reduce the area of unsupported fabric in the covering, the design alternated the main longitudinals with non-structural "reefing booms" mounted on kingposts which were adjustable using screw-jacks in order to tension the covering.[24] The pre-doped fabric proved unsatisfactory from the start, with panels splitting because of humidity changes before the airship had even left its shed.[25]

There were other innovative design features. Previously, ballast containers had been made in the form of leather "trousers", and one or other leg could be opened at the bottom by a cable-release from the control car. In R101, the extreme forward and aft ballast bags were of this type, and were locally operated, but the main ballast was held in tanks connected by pipes so that ballast could be transferred from one to another to alter the airship's trim using compressed air.[26] The arrangement for ventilating the interior of the envelope, necessary both to prevent any build-up of escaped hydrogen and also to equalise pressure between the outside and inside, was also innovative. A series of flap-valves were situated at the nose and stern of the airship cover (those at the nose are clearly visible in photographs) to allow air to enter when the airship was descending, while a series of vents was arranged around the circumference amidships to allow air to exit during ascent.[25]

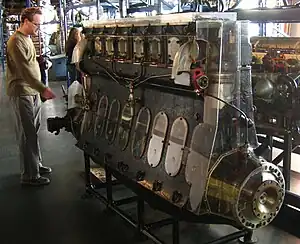

Engines

Heavy oil (diesel) engines were specified by the Air Ministry because the airship was intended for use on the India route, where it was thought that high temperatures would make petrol an unacceptable fire hazard because of its low flash point. A petrol explosion had been a major cause of fatalities in the loss of R38 in 1921.[27]

Initial calculations were based on the use of seven Beardmore Typhoon six-cylinder heavy-oil engines which were expected to weigh 2,200 lb (1,000 kg) and deliver 600 bhp (450 kW) each.[28] When the development of this engine proved impractical, the use of the eight-cylinder Beardmore Tornado was proposed instead. This was an engine being developed by Beardmore, combining two four-cylinder engines which had originally been developed for railway use. In March 1925 these were expected to weigh 3,200 pounds (1,500 kg) and deliver 700 bhp (520 kW) each. Because of the increased weight of each engine, it was decided to use five, resulting in overall power being reduced from 4,200 bhp (3,100 kW) to 3,500 bhp (2,600 kW).

Severe torsional resonance of the crankshaft was encountered above 950 rpm, limiting the engine to a maximum of 935 rpm, giving an output of only 650 bhp (485 kW) with a continuous power rating at 890 rpm of 585 bhp (436 kW).[29] The engine was also considerably above estimated weight, at 4,773 lb (2,165 kg), over double the initial estimate.[29] Some of this excess weight was the result of the failure to manufacture a satisfactory lightweight aluminium crankcase.[30]

The original intention had been to fit two of the engines with variable-pitch propellers in order to provide reverse thrust for manoeuvring during docking. The torsional resonance caused the hollow metal blades of the reversing propellers to develop cracks near the hubs,[31] and as a short-term measure, one of the engines was fitted with a fixed-pitch reverse propeller, consequently becoming dead weight under normal flight conditions. [N 1] For the airship's final flight, two of the engines were adapted to be capable of running in reverse by a simple modification of the camshaft.[33]

Each engine car also contained a 40 bhp (30 kW) Ricardo petrol engine for use as a starter motor. Three of these also drove generators to provide electricity when the airship was at rest or flying at low speeds: at normal flight speeds the generators were driven by constant-speed variable-pitch windmills. The other two auxiliary engines drove compressors for the compressed air fuel and ballast transfer system. Before the final flight, one of the petrol engines was replaced by a Beverly heavy oil engine; to lessen the risk of fire, the petrol tanks could be jettisoned.[34]

Diesel fuel was contained in tanks in the transverse frames, the majority of the tanks having a capacity of 224 imp gal (1,018 L). A mechanism was provided for dumping fuel directly from the tanks in an emergency. By the use of tankage provided for weight compensation, when travelling with a light passenger load a total fuel load of 10,000 imp gal (45,000 L) could be carried.[35]

Crewing and control

In normal service, R101 carried a crew of 42. This consisted of two watches of 13 men under the officer of the watch, this duty being divided among the three principal ship's officers. In addition there were the chief navigator, the meteorological officer, the chief coxswain, the chief engineer, the chief wireless officer and the chief steward, who were not assigned to watches but were on duty as necessary, and four supernumeraries (three engineers and a radio operator) who were available to provide relief watch keeping if necessary, and an assistant steward, a cook and a galley boy who were on duty as required between 06:30 and 21:30.[36] The minimum crew requirement, as specified in the airship's Certificate of Airworthiness, was 15 men.

The control car was occupied by the duty officer of the watch and the steering and altitude coxswains, who respectively controlled the rudder and elevators using wheels similar to a ship's wheel. The engines were individually controlled by an engineer in each of the engine cars, orders being given by an individual telegraph to each car. These moved an indicator in the engine car to signal the desired throttle setting and also rang a bell to draw attention to the fact that an order had been transmitted.

Accommodation

The passenger accommodation was spread over two decks within the envelope and as first designed included 50 passenger cabins for one, two, or four people, a dining room for 60 people, two promenade decks with windows down the sides of the airship, a spacious lounge of 5,500 square feet (510 m2)[3] and an asbestos-lined smoking room for 24 people. Most of the passenger space was on the upper deck, with the smoking room, kitchen and washrooms, crew accommodation, as well as the chart room and radio cabin on the lower deck.[37] The control car was immediately under the forward section of the lower deck and was reached by a ladder from the chart room.

Walls were made of doped linen painted in white and gold. Weight-saving measures included wicker furniture and aluminium cutlery. The promenade windows were lightweight "Cellon" instead of the intended glass, and one set was removed as part of later weight-saving measures.

Operational history

1929

The lengthy process of inflating the R101's hydrogen gasbags began on 11 July 1929 and was complete by 21 September. With the airship now airborne and loosely tethered within the shed, it was now possible to carry out lift and trim trials. These were disappointing. A design conference held on 17 June 1929 had estimated a gross lift of 151.8 tons and a total airframe weight, including the power installation, of 105 tons. The actual figures proved to be a gross lift of 148.46 tons and a weight of 113.6 tons.[38] Moreover, the airship was tail-heavy, a result of the tail surfaces being considerably above estimated weight. In this form, a flight to India was out of the question. Airship operations under tropical conditions were made more difficult by the loss of lift in high air temperatures: the loss of lift in Karachi (then part of British India) was estimated to be as much as 11 tons for an airship the size of R101.[39]

On 2 October the press were invited to Cardington to view the finished airship.[40] However, weather conditions made it impossible to take it out of the shed until 12 October, when it was walked out by a ground-handling party of 400. The event attracted a huge number of spectators, with surrounding roads a solid line of cars. The moored airship continued to attract spectators, and it was estimated that more than a million people had made the trip to Cardington to see R101 at the mast by the end of November.[41]

The flying programme was influenced by the Air Ministry's need to generate favourable publicity, illustrating the political pressures which weighed upon the programme. Noël Atherstone, the first officer, commented in his diary on 6 November: "All these window-dressing stunts and joy-rides before she has got an Airworthiness Certificate are quite wrong, but there is no-one in the RAW [Royal Airship Works] executive who has got the guts to put their foot down and insist on trials being free of joy-rides".[42] Atherstone's remarks were occasioned by a lunch held on the airship for delegates to a conference on empire legislation, but there were several similar occasions.

R101 made its first flight on 14 October. After a short circuit over Bedford, course was set for London, where it passed over the Palace of Westminster, St Paul's Cathedral and the City, returning to Cardington after a flight lasting five hours 40 minutes. During this flight the servos were not used, without any difficulty being experienced in controlling the airship.[43] A second flight lasting nine hours 38 minutes followed on 18 October, with Lord Thomson among the passengers, after which R101 was briefly returned to the shed to enable some modifications to be made to the starting engines.[41] A third flight lasting seven hours 15 minutes was made on 1 November, during which it was flown at full power for the first time, recording a speed of 68.5 mph (110.2 km/h):[44] even at full speed it was not found necessary to use the control servos. During this flight, it circled over Sandringham House, observed by King George V and Queen Mary, flew on to the previous Secretary of State for Air's country house near Cromer, then to Norwich over Boulton & Paul's works and aerodrome before returning by Newmarket and Cambridge.[45] On 2 November the first night flight was made, slipping the mast at 20:12 before heading south to fly over London and Portsmouth before attempting a speed trial over a 43 mi (69 km) circuit over the Solent and the Isle of Wight. These trials were frustrated by pipe breakages in the cooling systems of two of the engines, a problem later solved by replacing the aluminium piping with copper. It returned to Cardington around 09:00, the mooring operation ending in a minor accident, damaging one of the reefing booms at the bow.[46]

On 8 November, a short flight – purely for public relations purposes – was made, carrying 40 passengers, including the Mayor of Bedford and various officials. To accommodate this load, the airship was flown with only a partial fuel and ballast load and was inflated to a pressure height of 500 ft (150 m). In Atherstone's words, it "staggered round the vicinity of Bedford for a couple of hours" before returning to the mast.

Two days later, the wind began to rise and gales were forecast. On 11 November, the wind touched 83 mph (134 km/h), with a maximum gust speed of 89 mph (143 km/h). Although the ship's behaviour at the mast gave cause for a good deal of satisfaction, there was nevertheless some cause for concern. The movement of the ship had caused considerable movement of the gasbags, the surging being described by Coxswain "Sky" Hunt as being around four inches (ten cm) from side to side and "considerably more" longitudinally. This caused the gasbags to foul the framework, and the resulting chafing caused the gasbags to be holed in many places.[47]

A sixth flight was made on 14 November, to test the modifications that had been made to the cooling system and the repairs to the gasbags, carrying a load of 32 passengers, including 10 MPs with a special interest in aviation and a party of Air Ministry officials headed by Sir Sefton Brancker, the Director of Civil Aviation.[48]

On 16 November, it had been planned to carry out a demonstration flight for a party of 100 MPs, a scheme that had been suggested by Lord Thomson in the expectation that few would wish to take advantage of the offer; in the event, it was oversubscribed.[49] The weather on the day was unfavourable, and the flight was rescheduled. The weather then cleared, and on the following day, R101 slipped the mast at 10:33 to carry out an endurance trial, planned to last at least thirty hours. R101 passed over York and Durham before crossing the coast and flying over the North Sea as far north as Edinburgh, where it turned west towards Glasgow. During the night, a series of turning trials were made over the Irish Sea, after which the airship was flown south to fly over Dublin (the home town of R101's Captain, Carmichael Irwin) before returning to Cardington via Anglesey and Chester. After some delay in finding Cardington owing to fog, R101 was secured to the mast at 17:14, after a flight lasting 30 hours 41 minutes. The only technical problem encountered during the flight was with the pump for transferring fuel, which broke down several times, although subsequent examination of the engines showed that one was on the point of suffering a failure of a big end bearing.[50]

The flight for the MPs had been rescheduled for 23 November. With the barometric pressure low, R101 lacked sufficient lift to carry 100 passengers, even though all but a bare minimum of fuel was drained off and the ship lightened by removing all unnecessary stores. The flight was cancelled because of the weather, but not before the politicians had arrived at Cardington: they accordingly embarked and had lunch while the ship rode at the mast, only kept in the air by dynamic lift produced by the 45 mph (72 km/h) wind.[51] Following this, R101 remained at the mast until 30 November, when the wind had dropped enough for it to be walked back into the shed.

While the initial flight trials were being carried out, the design team examined the lift problem. Studies identified possible weight savings of 3.16 tons. The weight-saving measures included deleting twelve of the double-berth cabins, removing the reefing booms from the nose to frame 1 and between frames 13 to 15 at the tail, replacing the glass windows of the observation decks with Cellon, removing two water ballast tanks, and removing the servo mechanism for the rudder and elevators.[52] Letting the gasbags out would gain 3.18 tons extra lift, although Michael Rope considered this unwise,[53] since there were thousands of exposed fixings protruding from the girders; chafing of the gasbags would have to be prevented by wrapping these in strips of cloth. To further increase lift, an extra bay of 500,000 cu ft (14,000 m3) capacity could be installed. This would deliver an extra nine tons disposable lift. After much consultation, all these proposed measures were approved in December. Letting out the gasbags and the weight-saving measures were begun. Delivery by Boulton & Paul of the metalwork for the extra bay was expected to take place in June.

1930

R101's outer cover was also giving cause for concern. An inspection on 20 January 1930 by Michael Rope and J. W. W. Dyer, head of the Fabric Section at Cardington, revealed serious deterioration of the fabric on the top of the airship in areas where rainwater had accumulated, and a decision was made to add reinforcement bands along the whole length of the envelope. Further tests undertaken by Rope had shown that its strength had deteriorated alarmingly. The original specified strength for the cover was a breaking strain of 700 lb per foot run (10 kN/m): the actual strength of samples was at best 85 lb (1.24 kN/m). The calculated load at a speed of 76 mph (122 km/h) was 143 lb per foot run (2.09 kN/m). A further inspection of the cover on 2 June found many small tears had developed.[54] An immediate decision was taken to replace the pre-doped cover with a new cover which would be doped after fitting. This would take place following the flights which had been planned for June with the purpose of displaying R101 to the public at the Hendon Air Show; for these flights, the cover would be further reinforced. Confirmation of the poor state of the cover came on the morning of 23 June, when R101 was walked out of the shed. It had been at the mast for less than an hour in a moderate wind when an alarming rippling movement was observed and shortly afterwards, a 140 ft (43 m) split in the cover appeared on the starboard side of the airship. It was decided to repair this at the mast and to add more strengthening bands. This was done by the end of the day, but the next day a second, shorter, split occurred. This was dealt with in the same way, and it was decided that if the reinforcing bands were added to the repaired area the scheduled appearance at the Hendon Air Show could be made.[55]

R101 made three flights in June, totalling 29 hours 34 minutes duration. On 26 June, a short proving flight was made, the controls – no longer servo-operated – being described as "powerful and fully adequate".[56] At the end of this flight, the R101 was found to be "flying heavy" and two tons of fuel oil had to be jettisoned in order to lighten the airship for mooring. This was initially attributed to changes in air temperature during the flight. On the following two days, R101 made two flights, the first to take part in the rehearsal for the RAF display at Hendon and the second to take place in the display itself. These flights revealed a problem with lift, considerable jettisoning of ballast being necessary. During this time, Atherstone was replaced by Captain G.F. Meager, who was normally the first officer on R100. Meager was "alarmed" by the heaviness of R101, as after 10 hours of flight, R100 would have been considerably light due to fuel consumption. Meager observed that it was the first time he had "the wind up" in an airship.[57] Meager had dropped a ton of ballast, and in order to weigh off the R101 for mooring, Flight Lieutenant Irwin was required to dump 10 tons of water and fuel oil.[58][59] An inspection of the gasbags revealed a large number of holes, a result of the letting-out of the gasbags which allowed them to foul projections on the girders of the framework.[60] When the gas bag restraints were loosened to allow more gas capacity (R101B) it came to the attention of Dr. Eckener. His concern was conveyed to Willy von Meister, the Deutsche Zeppelin-Reederei representative in the US, who was visiting Luftschiffbau Zeppelin at Lake Constance. Dr. Eckener was concerned that the gas bags would be holed by wearing upon the structure and loss of gas would occur. Von Meister stopped on his way back to the US to visit his mother and met Lord Thompson to convey Dr. Eckener's offer of technical help. Lord Thompson listened cordially, thanked von Meister, and informed him that padding was being installed and British designers felt that would suffice.[61]

Concern was also raised over the possibility of loss of gas through the valves, which were of an innovative design by Michael Rope. Airship valves are intended primarily to vent gas automatically if pressure in the cells rises to the point that the bag might rupture; they are also used to adjust lift for handling. It was suspected that valves could open when the airship rolled heavily or when flapping of the outer cover caused localised low pressure, but after an examination of their operation, F. W. McWade, the Air Inspectorate Department inspector at Cardington, concluded that their operation was satisfactory and they were not likely to have been the cause of any significant loss of gas.[62]

As an experimental aircraft, R101 had been operating under a temporary "Permit to Fly", the responsibility of McWade. On 3 July, bypassing his immediate superior, McWade wrote a letter to the Director of Aeronautical Inspection, Lieutenant-Colonel H. W. S. Outram, expressing his unwillingness to recommend either an extension to the permit or the granting of the full Certificate of Airworthiness which would be necessary before the airship could fly in the airspace of other countries. His concern was that the padding on the framework was inadequate to protect the gasbags from chafing, the harnessing having been let out so that they were "hard up against the longitudinal girders", and that any surging of the gasbags would tend to loosen the padding, rendering it ineffective. He also expressed doubts about the use of padding, considering that it made inspection of the airframe more difficult and would also tend to trap moisture, making problems with corrosion more likely.[63] Outram, who knew little about airships, reacted to this by consulting Colmore, now Director of Airship Development, from whom he received a reassuring reply. The matter was taken no further.[64]

R101 entered its shed for the extension on 29 June. At the same time, the gasbags were given a complete overhaul, two of the engines were replaced by the adapted engines capable of running in reverse, and most of the cover was replaced. The original cover was left in place between frames 3 and 5 and in two of the bays at the tail.[65] These parts of the cover had been doped after fitting and were therefore thought to be satisfactory, even though an inspection by McWade had found that some areas where reinforcements had been stuck on with a rubber solution were seriously weakened; these areas were further reinforced, using dope as an adhesive.[66]

A schedule was drawn up by the Air Ministry for R101 to undertake the flight to India in early October, in order that the flight would be made during the Imperial Conference which was to be held in London. The entire programme was intended to improve communication with the Empire, and it was hoped that the flight would generate favourable publicity for the airship programme. The final trial flight of R101 was originally scheduled for 26 September 1930, but high winds delayed the move from the shed until 1 October. That evening, R101[67] slipped the mast for its only trial flight before setting off for India. This lasted 16 hours 51 minutes and was undertaken under near-ideal weather conditions; because of the failure of the oil cooler in one engine, it was not possible to carry out full-speed trials. The flight was curtailed in order to prepare the airship for the flight to India.[68]

Despite the lack of full endurance and speed trials, and the fact that a proper investigation of the aerodynamic consequences of the extension had not been fully completed by the NPL, a Certificate of Airworthiness was issued on 2 October, the Inspectorate expressing their complete satisfaction with the condition of R101 and the standards to which the remedial work had been carried out. The certificate was handed over to H. C. Irwin, the ship's captain, on the day of its flight to India.[69]

Final flight

R101 departed from Cardington on the evening of 4 October 1930 for its intended destination of Karachi, via a refuelling stop at Ismaïlia in Egypt, under the command of Flight Lieutenant Carmichael Irwin. Lord Thomson, Secretary of State for Air; Sir Sefton Brancker, Director of Civil Aviation; Squadron Leader William Palstra, RAAF Air Liaison Officer (ALO) to the British Air Ministry; Director of Airship Development Reginald Colmore; and both Lt. Col. V. C. Richmond and Michael Rope were passengers.[70]

The weather forecast on the morning of 4 October was generally favourable, predicting south to south-westerly winds of between 20 and 30 m.p.h. (32 and 48 km/h) at 2,000 ft (610 m) over northern France, with conditions improving over southern France and the Mediterranean Sea.[71] Although the mid-day forecast indicated some deterioration in the situation, this was not considered to be alarming enough to cancel the planned voyage. A course was planned which would take R101 over London, Paris and Toulouse, crossing the French coast near Narbonne.

Fine rain was beginning to fall when, at dusk, with all the crew and passengers aboard, R101 readied for departure. Under the illuminating spotlights, the jettisoning of water ballast to bring the airship into trim was clearly visible. Squadron Leader Booth, the commander of R100, was watching the departure from the tower's observation gallery and estimated that two tons had been discharged from the nose and a further ton from the midships tanks.[72] R101 cast off from the mast at 18:36 GMT to a cheer from the crowd which had gathered to witness the event, gently backed from the tower, and, as another ton of ballast was jettisoned, the engines were opened up to about half power and the airship slowly began to climb away, initially heading northeast to fly over Bedford before making a 180° turn to port to pass north of Cardington.

At about 19:06 the duty engineer in the aft engine car reported an apparent oil pressure problem. At 19:16, he shut the engine down, and after a short discussion with the chief engineer, work began to replace the oil gauge, since there was nothing apparently wrong with the engine. With one engine stopped, airspeed was reduced by around 4 mph (6 km/h) to 58.7 mph (94.5 km/h)[73]

At 19:19, having flown 29 mi (47 km) but still only 8 mi (13 km) from Cardington, a course was set for London. At 20:01, R101, by now over Potters Bar, made its second report to Cardington, confirming the intention to proceed via London, Paris and Narbonne, but making no mention of the engine problem. By that point, the weather had deteriorated, and it was raining heavily. Flying around 800 ft (240 m) above the ground, the airship passed over Alexandra Palace before changing course slightly at the landmark clock tower of the Metropolitan Cattle Market north of Islington, and thence over Shoreditch to cross the Thames in the vicinity of the Isle of Dogs, passing over the Royal Naval College at Greenwich at 20:28. The airship's progress, flying with its nose pointing some 30 degrees to the right of its track, was observed by many who braved the rain to watch it pass overhead.[73]

An update of the meteorological situation was received at 20:40.[74] The forecast had deteriorated severely, south-westerly winds of up to 50 mph (80 km/h) with low cloud and rain being predicted for northern France, and similar conditions over central France. That this caused concern on board is demonstrated by the request for more detailed information, which was transmitted at 21:19, by which time R101 was near Hawkhurst, Kent. It is possible that an alternative course was being considered. At 21:35 R101 crossed the English coast near Hastings and at 21:40 transmitted a progress report back to Cardington, mentioning that recovery of rainwater into the ballast tanks was taking place but again not reporting the engine problem. At 22:56 the aft engine was restarted. By now the wind had risen to about 44 mph (71 km/h) with strong gusts, but a further meteorological report received shortly after the airship had crossed the coast had been encouraging about weather conditions south of Paris.[75]

The French coast was crossed at the Point de St Quentin at 23:36 GMT, around 20 mi (32 km) east of the intended landfall.[76] A new course was set to bring R101 over Orly, based on an estimated wind direction of 245 degrees and speed of 35 mph (56 km/h). The intended course would have taken R101 four miles west of Beauvais, but the estimated wind speed and direction were inaccurate, as a result of which the R101's track was to the east of its intended course. This error would have become apparent when, at about 01:00, R101 passed over Poix-de-Picardie, a distinctive hilltop town that would have been readily recognisable to the navigation officer, Squadron Leader E.L. Johnston. Accordingly, R101 changed course: the new course would take it directly over the 770 ft (230 m) Beauvais Ridge, an area notorious for turbulent wind conditions.[77]

At 02:00 the watch was changed, Second Officer Maurice Steff taking over the command from Irwin. R101 was at this point "flying heavy", relying on dynamic lift generated by forward airspeed to maintain altitude, estimated by the Board of Inquiry as at least 1,000 ft (300 m) above the ground.[78] At about 02:07 R101 went into a dive from which it slowly recovered, probably losing around 450 ft (140 m). As it did so Rigger S. Church, who was returning to the crew quarters to come off duty, was sent forward to release the forward emergency ballast bags,[68] which were locally controlled. This first dive was steep enough to cause A. H. Leech, the foreman engineer from Cardington, to be thrown from his seat in the smoking room and to wake Chief Electrician Arthur Disley, who was dozing in the switch room next to the chart cabin. As the airship recovered, Disley was roused by Chief Coxswain G. W. Hunt, who then went to the crew quarters, calling out, "We're down, lads" in warning. As this happened the airship went into a second dive and orders to reduce speed to slow (450 rpm) were received in the engine cars. Before Engineer A. J. Cook, on duty in the left-hand midships engine car, could respond, the airship hit the ground at the edge of a wood outside Allonne, 2.5 mi (4 km) southeast of Beauvais, and immediately caught fire. The reason for the order to reduce speed is a matter for conjecture because this would have caused the airship to lose dynamic lift and adopt a nose-down attitude. The subsequent inquiry estimated the impact speed at around 13 mph (21 km/h), with the airship between 15° and 25° nose down.[79]

_(2).jpg.webp)

Forty-six of the fifty-four passengers and crew were killed immediately. Church and Rigger W. G. Radcliffe survived the crash but later died in hospital in Beauvais, bringing the total of dead to 48. Of the six eventual survivors, four (including Cook) were engineers in the engine cars outside the hull; Leech and Disley were the only survivors from within the main cabin.[68]

Memorials

The bodies were returned to England, and on Friday 10 October a memorial service took place at St Paul's Cathedral while the bodies lay in state in Westminster Hall at the Palace of Westminster. Nearly 90,000 people queued to pay their respects: at one time the queue was half a mile long, and the hall was kept open until 00:35 to admit them all.[80] The following day, a funeral procession transferred the bodies to Euston station through streets crowded with mourners. The bodies were then taken to Cardington village for burial in a common grave in the cemetery of St Mary's Church. A monument was later erected,[81] and the scorched Royal Air Force roundel which R101 had flown on its tail is on display, along with a memorial tablet, in the church's nave.[82] On 1 October 1933, the Sunday before the third anniversary of the crash, a memorial[83] to the dead near the crash site was unveiled by the side of Route nationale 1 near Allonne. There is also a memorial marker on the actual crash site.[84]

The Church of the Holy Family and St Michael, a Roman Catholic church in Kesgrave, Suffolk, was built in 1931 in memory of Squadron Leader Michael Rope, who was a Catholic. Suspended from the nave roof is a model of R101.[85]

Official inquiry

The Court of Inquiry was led by the Liberal politician Sir John Simon, assisted by Lieutenant-Colonel John Moore-Brabazon and Professor C.E. Inglis.[86] The inquiry, held in public, opened on 28 October and spent 10 days taking evidence from witnesses, including Professor Leonard Bairstow and Dr. Hugo Eckener of the Zeppelin company, before adjourning in order to allow Bairstow and the NPL to perform more detailed calculations based on wind-tunnel tests on a specially made model of R101 in its final form. This evidence was presented over three days ending on 5 December 1930. The final report was presented on 27 March 1931.

The inquiry examined most aspects of the design and construction of R101 in detail, with particular emphasis on the gasbags and the associated harnessing and valves, although very little examination of the problems that had been encountered with the cover was made. All the technical witnesses provided unhesitating endorsement of the airworthiness of the airship prior to its flight to India. An examination was also made of the various operational decisions that had been made before the airship undertook its final voyage.

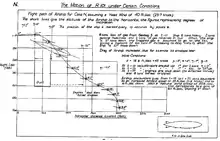

The possibility of the crash having been the result of a prolonged loss of gas caused by leakage or loss through the valves was discounted since this explanation did not explain the airship's behaviour during its last moments: moreover the fact that the officers on duty had changed watch routinely implied that there had been no particular cause for alarm a few minutes before the crash. The recent change of watch was considered to be a possible contributory factor to the accident, since the new crew would not have had time to get the feel of the airship. It was also considered most unlikely that the accident had been solely caused by a sudden downdraught. A sudden and catastrophic failure was seen as the only explanation. The inquiry discounted the possibility of structural failure of the airframe. The only major fracture found in the wreckage was at the rear of the new framework extension but it was considered that this had either occurred on impact or more probably been caused by the intense heat of the subsequent fire. The inquiry came to the conclusion that a tear had probably developed in the forward cover, this in turn causing one or more of the forward gasbags to fail. Evidence presented by Professor Bairstow showed that this would cause the R101 to become too nose-heavy for the elevators to correct.[87] The want of sufficient altitude was considered by the R101 Enquiry and must be considered given that the aircraft was flying in an area of reducing atmospheric pressure. The same evening, the Graf Zeppelin at Frankfurt was reading 400 feet high. A similar error over France would have put the R101 400 feet lower than her intended height.[88] The altimeter could have been corrected while flying across the channel by timing the flare drop before ignition, but over France there was no way to determine altimeter correction. Sightings by observers reporting very low altitudes across France and the belief by the crew that they were at a safe altitude according to the altimeter could both be true. The question of sufficient altitude was considered by the R101 Enquiry but not the attendant issue of altimeter correction.[89]

The cause of the fire was not established. Several hydrogen airships had crashed in similar circumstances without catching fire. The inquiry thought that it was most probable that a spark from the airship's electrics had ignited escaping hydrogen, causing an explosion. Other suggestions put forward included the ignition of the calcium flares carried in the control car on contact with water,[90] electrostatic discharge or a fire in one of the engine cars, which carried petrol for the starter engines. All that is certain is that it caught fire almost at once and burned fiercely. In the extreme heat, the fuel oil from the wreck soaked into the ground and caught fire; it was still burning when the first party of officials arrived by air the next day.[91]

The inquiry considered that it was "impossible to avoid the conclusion that the R101 would not have started for India on the evening of October 4th if it had not been that matters of public policy were considered as making it highly desirable that she should do so", but considered this to be the result of all concerned being eager to prove the worth of R101, rather than direct interference from above.[92]

Aftermath

The crash of R101 ended British interest in dirigibles during the pre-war period. Thos W Ward Ltd of Sheffield salvaged what they could of the wreckage,[93] the work continuing through 1931. Although it was stipulated that none of the wreckage should be kept for souvenirs,[94] Wards made small dishes impressed with the words "Metal from R101", as they frequently did with the metal from ships or industrial structures on which they had worked.

The Zeppelin Company purchased five tons of duralumin from the wreck.[68] The airship's competitor, R100, despite a more successful development programme and a satisfactory, although not entirely trouble-free, transatlantic trial flight, was grounded immediately after R101 crashed. The R100 remained in its hangar at Cardington for a year whilst the fate of the Imperial Airship programme was decided. In December 1931, the R100 was broken up and sold for scrap.[95]

At the time, the Imperial Airship Scheme was a controversial project because of the large sums of public money involved and because some doubted the utility of airships.[96] Subsequently, there has been controversy about the R101's merits. The extremely poor relationship between the R100 team and both Cardington and the Air Ministry created a climate of resentment and jealousy that may have rankled. Nevil Shute Norway's autobiography was serialised by the Sunday Graphic on its publication in 1954 and was misleadingly promoted as containing sensational revelations,[97] and the accuracy of his account is a cause of contention among airship historians.[98] Barnes Wallis later expressed scathing criticism of the design although they may in part reflect personal animosities. Nevertheless, his listing of Richmond's "overweening vanity" as a major cause of the debacle and the fact that he had not designed it as another say little for his objectivity.[99]

On 27 November 2014, 84 years after the disaster, Baroness Smith of Basildon, together with members of the Airship Heritage Trust, unveiled a memorial plaque to the R101 in St Stephens Hall in the Palace of Westminster.[100]

In popular culture

- The Doctor Who audio play Storm Warning is set aboard R101 during its voyage, with the Eighth Doctor's new companion Charley Pollard being a passenger on the airship; her time with the Doctor leaves him conflicted when he realises that historical records suggest that Charley was meant to die on R101 if he had not saved her.[101]

- R101 figured prominently in the book The Airmen Who Would Not Die by John G. Fuller (ISBN 978-0399122644), which tells of a purported psychic vision of the disaster years before by medium Eileen J. Garrett, and a seance with the deceased officers after the disaster.[102]

- R101 is the subject of the rock opera ("songstory") Curly's Airships (2000) by Judge Smith.[103][104]

- R101 has been featured in the TV series, Britain's Greatest Machines with Chris Barrie on the National Geographic Channel.[105]

- The Iron Maiden song "Empire of the Clouds" composed by Bruce Dickinson and featured on the 2015 album The Book of Souls, is about the R101 and its final flight.[106]

- The Monty Python sketch "Historical Impersonations" features Napoleon (Terry Jones) as the R101 disaster.[107]

- In John Crowley's 1991 novella "Great Work of Time," the destruction (or non-destruction) of R101 is one of the linchpin events whose occurrence (or non-occurrence) marks a particular branching point of the possible timestream which ends the novel.[108]

- The progressive rock band Lifesigns' 2017 album Cardington features both the R101 and its hangar, both on the artwork and on the title track.[109]

Specifications (R101 after extension)

General characteristics

- Crew: 42 (final flight)[110] (15 minimum)[111]

- Length: 777 ft 0 in (236.8 m) [4]

- Diameter: 131 ft 4 in (40 m) [4]

- Height: 140 ft 0 in (42.67 m) including control car[112]

- Volume: 5,509,753 cu ft (156,018.8 m3) [4]

- Empty weight: 257,395 lb (116,857 kg) [113]

- Useful lift: 55,268 lb (25,069 kg) [113]

- Powerplant: 5 × Beardmore Tornado 8-cylinder inline Diesel (2 reversing), 585 hp (436 kW) each

- Propellers: 2-bladed, 16 ft (4.9 m) diameter [111]

Performance

- Maximum speed: 71 mph (114 km/h, 62 kn) [4]

- Cruise speed: 63 mph (101 km/h, 55 kn)

- Range: 4,000 mi (6,437 km, 3,500 nmi)

See also

References

Notes

- This decision to incorporate a single-purpose engine astonished Shute and the other engineers on the R100 team.[32]

Citations

- Shute 1954, p. 77.

- "R101 Passenger List." Airship Heritage Trust via Airshipsonline. Retrieved: 27 August 2010.

- Popular Science Monthly: Keeping Pace with Aviation. Bonnier Corporation. January 1930. p. 41.

- "R101". Airship Heritage Trust via Airshipsonline.com. Retrieved: 23 July 2008.

- Report of the R101 Inquiry 1931, p. 7.

- Higham 1961, pp. 283–84.

- Masefield 1982, p. 30.

- Philpott, Ian: The Royal Air Force – Volume 2: An Encyclopedia of the Inter-War Years, pp. 4-9.

- Sprigg 1931, p. 128.

- Masefield 1982, p. 454.

- Report of the R101 Inquiry 1931, p. 14.

- Masefield 1982, p. 111.

- Masefield 1982, pp. 204–05, fn.

- Masefield 1982, p. 51.

- Flight 10 October 1930, p. 1126.

- "Written Answers." Hansard, 3 May 1926.

- Polmar, Norman; Moore, Kenneth J. (2004). Cold War Submarines: The Design and Construction of U.S. and Soviet Submarines. Potomac Books, Inc. ISBN 9781597973199.

- WISE. "Inspiration | Women in Aviation, the female inventor of the 'Lyon Shape'". www.wisecampaign.org.uk. Archived from the original on 25 August 2017. Retrieved 18 June 2017.

- "Division of the Design Work." Flight, 29 November 1928.

- "His Majesty's Airship R100: The construction of R101."Flight (supplement), 29 November 1928, p. 88. Archived 5 November 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- Masefield 1982, p. 457.

- Morpurgo 1982, pp. 132–33.

- Report of the R101 Inquiry 1931, pp. 39–40.

- Masefield 1982, p. 470.

- Report of the R101 Inquiry 1931, p. 31.

- "R101."Flight, 29 November 1929, p. 1094. Archived 21 March 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- "Boulton and Paul – the R101." Archived 9 November 2009 at the Wayback Machine norfolkancestors.org. Retrieved: 27 August 2010.

- Masefield 1982, p. 464.

- Masefield 1982, p. 69.

- Report of the R101 Inquiry p. 37

- The Engineer, October 1930

- Shute 1954, p. 74.

- "R101 Has Two Reversible Engines". Flight. Vol. XXII, no. 1135. 26 September 1930. p. 1076. Archived from the original on 17 December 2013.

- "R101." Flight, 11 October 1929, p. 1095.

- Flight 11 October 1929, pp. 1093–94.

- Masefield 1982, pp. 517–19.

- "Airships: R101 Interior." Airship Heritage Trust via Airshipsonline.com. Retrieved: 27 August 2010.

- Masefield 1982, pp. 475–76.

- Masefield 1982, p. 293.

- Masefield 1982, pp. 109–14

- Masefield 1982, pp. 131–32

- Swinfield 2012, p. 262

- "R101". The Times. No. 45335. London. 16 October 1929. col C, p. 14.

- Masefield 1982 p. 133

- "R101 At Full Speed". The Times. No. 45350. London. 2 November 1929. col D, p. 9.

- Masefield 1982, pp. 13–15

- Masefield 1982 pp. 137–38

- Masefield 1982, p. 139

- Masefield 1982, p. 128

- Masefield 1982 pp. 141–45

- Masefield 1982, pp. 146–47

- Masefield 1982, p. 151.

- Masefield 1982, p. 226.

- Masefield 1982, p. 206.

- Report of the R101 Inquiry 1931 p. 43

- Masefield 1982, p. 213.

- Meager 1970, p. 190.

- Meager 1970, p. 191.

- Masefield 1982, p. 221.

- Masefield 1982, p. 222.

- Meyer 1991, pp. 200–01.

- Masefield 1982, p. 228.

- Report of the R101 Inquiry 1931, p. 50.

- Report of the R101 Inquiry 1931 p. 51

- Masefield 1982, pp. 301–02.

- Report of the R101 Inquiry 1931, p. 93. (fn)

- "The British Airship R101 over Hinckley in 1930". www.hinckleypastpresent.org.

- "Airships: R101 Crash." Airship Heritage Trust via Airshipsonline. Retrieved: 27 August 2010.

- Report of the R101 Inquiry 1931, p. 56.

- "R101 Passenger List." Airship Heritage Trust via Airshipsonline. Retrieved: 27 August 2010.

- Masefield 1982, p. 337.

- Masefield 1982, p. 350.

- Masefield 1982, p. 373.

- Masefield 1982, p. 376.

- Masefield 1982, p. 383.

- Masefield 1982, p. 389.

- Masefield 1982, p. 396.

- Report of the R101 Inquiry 1931, p. 81.

- Report of the R101 Inquiry1931, p. 79.

- "Lying In State". The Times. No. 45641. London. 11 October 1930. col C, p. 12.

- Latitude and longitude: 52.119524 -000.416366 (visible in Google Earth); see also https://welweb.org/ThenandNow/R-101-2.html

- "R101 Victims Funeral and Memorial." Archived 16 October 2012 at the Wayback Machine Bedfordshire.gov. Retrieved: 5 October 2012.

- Latitude and longitude: 49°24'16.09"N 2° 7'19.05"E

- Latitude and Longitude: 49.390650 002.110709 as stated at https://welweb.org/ThenandNow/R-101-2.html

- "Kesgrave – Holy Family and St Michael". Catholic Trust for England and Wales and English Heritage. 2011. Archived from the original on 20 October 2021. Retrieved 9 December 2022.

- "R101 Inquiry." The Times (London), 28 October 1930, p. 14.

- "R 101 Inquiry". Flight. Vol. XXII, no. 1102. 12 December 1930. p. 1446. Archived from the original on 7 February 2018. Retrieved 4 March 2012.

- Higham, Robin. The British Rigid Airship, 1908–1931. G.T. Foulis & Co Ltd, London, UK 1961, p 315

- Report of the R101 Inquiry, 1931, p. 90.

- Chamberlain 1984, pp. 174–78.

- Leasor 1958, p. 151.

- Report of the R101 Inquiry, 1931, p. 95.

- "Outline of Progress, Commemorating 75 Years Industrial Service, 1878–1953, p. 17." explore.bl.uk. Retrieved: 27 October 2012.

- "Loss of R101." Flight, 24 October 1930.

- "Breaking Up the R101". Flight. Vol. XXIII, no. 1198. 11 December 1931. p. 1210. Archived from the original on 5 March 2016.

- Swinfield 2012, p. 146

- "Advertisement." Flight, 5 March 1954.

- Swinfield 2012, p. 141

- Morpurgo 1982, p. 187.

- "Airshipsonline R101 Plaque unveilled". /airshipsonline.com. Retrieved 20 January 2015.

- Thompson, Dave (2013). Doctor Who FAQ: All That's Left to Know About the Most Famous Time Lord in the Universe. Applause Theatre & Cinema Books. p. 226. ISBN 978-1480342958. Retrieved 3 October 2018.

- John G. Fuller (21 February 1978). "The Airmen Who Would Not Die". Kirkus Reviews. Retrieved 3 October 2018.

- Buckley, Peter (2017). The Rough Guide to Rock. Rough Guides. ISBN 978-1843531050. Retrieved 3 October 2017 – via Google Books.

- "Curly's Airships – Judge Smith – Songs, Reviews, Credits – AllMusic". AllMusic. Retrieved 3 October 2017.

- "Britain's Greatest Machines with Chris". National Geographic. Retrieved 3 October 2018.

- Lombardelli, Tiphaine (12 August 2015). "Bruce Dickinson (Iron Maiden) : la générosité dans l'âme". Radiometal.com (in French). Retrieved 12 August 2015.

- The Complete Monty Python's Flying Circus: All the Words. Vol. 1. Pantheon Books. 1989. p. 170. ISBN 978-0679726470. Retrieved 3 October 2018.

- Crowley, John (1990). "Great Work of Time". In Dozois, Gardner (ed.). The Year's Best Science Fiction: 7th Annual Collection. St. Martin's Press. p. 545. ISBN 978-0312044527. Retrieved 3 October 2018.

- "CD: Cardington". Lifesigns. Retrieved 27 April 2020.

- Masefield 1982, p. 517.

- "R101 Certificate of Airworthiness, 2 October 1930." airshipsonline.com. Retrieved: 4 March 2012.

- "His Majesty's Airship R 100". Flight. Vol. XXI, no. 1093. 6 December 1929. p. 1276. Archived from the original on 5 March 2016.

- Masefield 1982, p. 477.

Bibliography

- Chamberlain, Geoffrey. Airships: Cardington. Lavenham, Suffolk, UK: Terence Dalton Ltd., 1984. ISBN 0-86138-025-8.

- Fuller, John G. The Airman Who Would Not Die. New York: Putnam & Sons, 1979. ISBN 978-0-399-12264-4.

- Gilbert, James. The World's Worst Aircraft. Walton-on-Thames, UK: Michael Joseph, Third Edition 1975. ISBN 978-0-7181-1269-1.

- Grimwood, Terry. "R101: The Kesgrave Connection" (Essay). kesgrave.org.uk. Retrieved: 27 August 2010.

- Leasor, James (2001) [1957]. The Millionth Chance: The Story of the R101. London: Stratus Books. ISBN 978-0-7551-0048-4.

- Higham, Robin. The British Rigid Airship, 1908-1931. G.T. Foulis & Co Ltd, London, UK 1961.

- Masefield, Peter. To Ride The Storm: The Story of the Airship R101. London: William Kimber, 1982. ISBN 0-7183-0068-8.

- Meager, Captain George F. My Airship Flights 1915–1930. London: William Kimber, 1970. ISBN 0-7183-0331-8.

- Morpurgo, J.E. Barnes Wallis: A Biography. London: Longman, 1982 (2nd edition). ISBN 0-7110-1119-2.

- Meyer, Henry Cord. Airshipmen Businessmen and Politics 1890–1940, Smithsonian Institution Press. Washington D.C. and London, 1991. ISBN 1-56098-031-1.

- "R.101". Flight. Vol. XXI, no. 1085. 11 October 1929. pp. 1088–1095. Archived from the original on 5 March 2016.

- "Report of the R101 Inquiry." London: HMSO, 1931. via www.bedfordraob.org.uk

- Shute, Nevil. Slide Rule: Autobiography of an Engineer. London: William Heinemann, 1954. ISBN 1-84232-291-5.

- Sprigg, C. The Airship: Its Design, History, Operation and Future. London: Samson Low, Marston & Co, 1931.

- Swinfield, John. Airship: Design Development and Disaster. London: Conway, 2012. ISBN 978-1844-861385

- Venty, Arthur Frederick and Eugene M. Kolesnik. Airship Saga. Poole, Dorset, UK: Blandford Press, 1982. ISBN 978-0-7137-1001-4.

- Wintringham, T. H. "The Crime of R101." Labour Monthly, December 1930.

Further reading

- Hammack, Bill (2017). Fatal Flight: The True Story of Britain's Last Great Airship. Articulate Noise Books. ISBN 978-1-945441-01-1. Retrieved 6 February 2018.

- Poulsen, C M (29 November 1928), "Building the structure of R101", The Aircraft Engineer (Supplement to Flight), vol. XX, no. 1040, pp. 88–98 (1020e-1020p), archived from the original on 24 June 2015

- "The Loss of H.M. Airship R101". Flight. Vol. XXII, no. 1137. 10 October 1930. p. 1107. Archived from the original on 9 May 2015.

External links

- Tim Harford (29 November 2019). "The Deadly Airship Race" (Audio/Podcast). Cautionary Tales Episode 4. Retrieved 17 June 2022.

- The Airship Heritage Trust

- Britain's Million-Pound Monster Comes to London – Newsreel footage of the R101, probably of the test flight on 12 October 1929.

- List of documents held at the National Archives