R12 (cemetery)

R12 is a middle Neolithic cemetery located in the Northern Dongola Reach on the banks of the Seleim Nile palaeochannel of modern-day Sudan.[1] The site is dated to between 5000 and 4000 BC.[1] Centro Veneto di Studi Classici e Orientali excavated the site, within the concession of the Sudan Archaeological Research Society and after an agreement with it, between 2000 and 2003 over three digging seasons.[2] The first was in 2000 and 33 graves were discovered. The second was in 2001 and another 33 graves were discovered. The third was in 2003 and the last 100 graves were discovered.[2] There are 166 graves total at the site. Contents of the graves include ceramics, animal bones, grinding stones, human skeletons, and plant remains.[1]

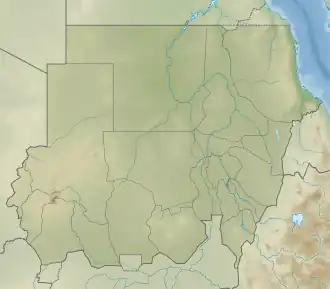

| R12 | |

|---|---|

R12 Site Location | |

| Location | Sudan |

| Coordinates | 19°08′N 30°32′E |

Excavation

The R12 cemetery is held within a mound-like formation spanning 1400m2. The mound is 2.9 meters above the surface of the plain. The cemetery within the mound has an area of about 650m2. The mound is a layer of Nile silt on top of an irregular sandy deposit. Underneath these two layers is a regularly deposited silt layer. Over the past 7000 years, wind and water have eroded the mound causing it to have the morphology that it did before excavation. Because some of this wind and water eroded the lower part of the mound, some skeletal remains and artifacts breached the body of the mound. These processes of erosion did not affect the graves in the top of the mound. This made them easily detectable as compared to the graves at the lower part.[2]

Grave contents

Some of the graves have filled with gravel or stones from processes of erosion. The graves were dug through the upper silt layer. Mud was placed on the walls of the grave to prevent falling sand. After the person was placed in the grave, they filled the grave with silt or small pebbles.[2] The people buried in the graves were usually placed on their left side. Direction of the body was aligned with the cardinal directions. It appears that when new graves were dug, they cut into older graves. The graves often contained pottery, tools, bone spatulas, mammal bone perforators. Bodies were adorned with ivory bracelets, stone and ivory bangles, stone necklaces, lip plugs, and stone pendants. Graves also contained pebbles, beads, and marine shells. Children were buried with furniture or distinctive signs of family. These children seem to have had the same treatment as adults. This is a sign that status is attributed at birth.[2]

Pottery

Ninety-five percent of the graves at R12 contain pottery. There are between one and nine pottery vessels in any given grave. At least 220 pottery vessels were found in total. Most of the pottery is made form fine sand temper and fired in an earthen kiln. Sometimes, the fine sand temper pottery contains mica. Other materials that the pottery could be partially made from are chaff, limestone splinters, and shells. The pottery was decorated and then smoothed and polished. Some of the pottery had stripes and was so polished that it gained a metallic brightness. Red or black spots were found on some of the pottery. This was caused by oxidation or reduction processes. There is evidence that the pottery was not made for only funerary purposes. Many of the pots show signs of prolonged use over fire which shows that it was used many times before placed in the graves. When a grave has more than one pot, they have similar or identical decorations. It is possible that this signifies that a certain group of people or family is associated with a decorative motif.[3]

Bowls

Most of the pottery found are bowls. These bowls were mainly hemispherical and were either restricted (47%) or unrestricted (32.5%). A distinctive type of bowl at R12 is a composite contour bowl with a carinated profile with the upper body going from straight to concave. The bowls ranged from a height of 2 cm to over 14 cm. The bowls found in Period 1 of R12 are composite with a sinuous profile. These bowls also have a complex decorated motif of dot impressions. Bowls with a rising lug handle, small bowls with depressions on the rim, and small colanders were only found in children's graves.[3]

Jars

Another form of pottery found are jars (12.5%). They range in shape from ovoid to globular. The jars ranged from a height of 10 cm to over 40 cm. A jar with covered with ochre powder and a complex dot decoration was found.[3]

Caliciform beakers

A third form of pottery found at R12 are caliciform beakers (8%). Sixteen complete beakers were found along with several fragments. Four different types of caliciform beakers were found at R12. The first type is decorated with wide horizontal bands. These bands are either dotted or are incised lines separated by undecorated bands. The internal rims had chains of hatched triangles. These caliciform beakers were between 20.6 cm and 33 cm in height.[2] The second type is decorated with hatched, oblique, regularly spaced bands covering the entire beaker. The rims are rounded on the inside and slightly flared out. The rims are decorated with clusters of dotted parallel lines. The third group of beakers have the same geometric pattern, rounded rim, rim decoration, and are between 18.4 cm and 21.5 cm tall. The fourth group of beakers are generally squat in shape and have thin horizontal bands with hatched dotted lines and rounded rims. The surface of the beakers are purposely imprecise, making the beakers seem less elegant than the other groups of beakers.[3]

Jewelry

Most of the jewelry found at R12 are bead bracelets, necklaces, and stone pendants. There are also a few examples of stone bracelets and ear or lip plugs. Jewelry is present in 21.69% of the graves at R12. Jewelry was found in 11 male graves, 9 female graves, and 14 child graves. Jewelry is absent in graves of people over the age of 50. This could suggest that jewelry was only available to a certain group within the population.[4]

Grave 92 included a bead-belt. Grave 60 contained a person wearing headband made out of ostrich eggshell beads.

Thirteen bead blanks were found inside a shell in Grave 38. They were made from agate and quartz flakes reduced to a cylindrical shape. After this, they were polished and perforated.[4] This grave was also home to the only in situ perforator found at R12, bone beads in various stages of production, thousands of ostrich eggshell beads, several pendants, and sandstone palettes. This particularly rich assemblage suggests this person may have been an artisan who specialized in the production of stone jewelry, with the perforator and palettes as their tools.[5]

Other beads were made from ochre, amazonite, or ostrich eggshells. Amazonite beads were made into a teardrop shape. It seems that all beads buried in R12 graves were constructed by the same people that utilized the cemetery. Ochre beads had the most specialized production because they are the most regular in measurement.[4]

Bracelets and necklaces

Fifteen bracelets were found at R12 across a total of nine graves. Forty necklaces were found at R12 across a total of 39 graves. Similar necklaces have been found at other Neolithic cemeteries in Nubia and Sudan. These bracelets and necklaces were made from various types of beads.[4]

Stone jewelry

Pendants, bangles, and lip/ear plugs are the common forms of stone jewelry found at R12. The stone pendants were made of small elongated pebbles of agate, carnelian, quartz, white and variegated stones. Sometimes the pendants were used as bracelets. Similar pendants are found in other Neolithic cemeteries in Sudan and Nubia. Stone bangles are made from a white stone that has not been identified. They were worn on the upper arm. There are no other objects like them found in any other Neolithic cemetery and there is no evidence for how they were made. Three lip plugs and one possible ear plug were found at R12. The three lip plugs are made of zeolite and are angular with a conical extremity. They were found in two separate graves. The third lip plug was found on the surface. Grave 18 possibly had an ear plug. In general, lip and ear plugs are common in other Neolithic cemeteries in Sudan and Nubia. There is no evidence for how the ear and lip plugs were made.[4]

Lithic tools

539 lithic tools and pieces were found from a total of 48 graves at R12. These tools and pieces are flakes, blades, cores, and debris. Because of the overabundance of flakes in the distribution, it can be assumed that the production was for flakes and blades were occasional byproducts. The most common material found in the graves is flint possibly taken from a nearby gravel deposit containing quartz, agate, carnelian, and chert.[6]

Debitage

Most of the debitage consists of flakes as a result of being struck by a hard-hammer. Not all of the debitage were complete. A majority of these flakes came from single-platform cores. There are also flakes from opposed-platform and multi-platform cores. Primary flakes are underrepresented which is strange because they are the first step of core flaking. Half of the debitage are flakes that still have part of the cortex. Most of the blades are single-platform core blades with flat butts. The lengths and widths of the flakes were distributed regularly meaning that the production of the flakes reached standardization. However, there is no evidence for any specific core preparation technique.[6]

Cores

There were a total of 51 cores recorded at the R12 site. Most of the 51 cores are made of flint from Nile pebbles. They were also made from quartz, agate, and one core from flint not from Nile pebbles. Three of the cores show blade scars. The others are flake cores. Some of the cores are found with their original debitage. Most core are single-platform which could be because they are less elaborate than multi-platform cores and thus easier to make. Sixteen of the thirty six single-platform cores are made of quartz. This is notable because quartz does not flake well. Nine of the cores are multi-platform cores. Multi-platform cores have more use than single-platform cores.[6]

Tools

135 tools were found at R12. Most of the tools were made of flint from Nile pebbles. Geometrics were the most common tool type found and are made from the finest raw materials. Backed pieces were the second most common tool type found followed by end-scrapers, perforators, notches/denticulates, and varia. The only type of geometric tool found are lunates. In some instances, the difference between lunates and backed pieces was ambiguous. The backed pieces found at R12 are different than other Northern African backed pieces in that they are not made on blades and are not elongated. Four scraper tools were found. Two perforators were found. Four notch/denticulates were found.[6]

Ritual and social context

Because the differing tools found at R12 is smaller than the actual amount of tools created by the people of R12, archaeologists can only make hypotheses about what the people were doing. It is also hard to tell which tools the people of R12 created and which tools were accumulated through trade. Even though the pottery at R12 shows change over the 600 active site years, the lithic assemblage does not. Most of the lithics seem to have been created for burial as they do not show signs of wear. Male and female graves contained lithics at significant percentages. This could mean that there was a somewhat equal division of labor.[6]

Grave 38 is considered the richest grave excavated at R12 and contained an adult male buried with the set of bead blanks discussed previously, bone tools, three large bowls, a small jar, and 87 lithic pieces, making this grave have the largest amount of lithics. He also was wearing a bracelet made from pebbles and a necklace made from carnelian, agate, amazonite, and shell beads. The presence of lithics and other artifacts in this grave could represent wealth in terms of quantity and variety of materials.[6][7]

Other stone tools

Stone tools are globally characteristic of the Neolithic. The stone tools found at R12 consist of axes, palettes, mace-heads, grinders, and other stone objects. Although most had known usage, many of the stone objects seem to have no purpose. The stone tools were mainly made from syenite, sodalite, soapstone, sandstone, and pumice. These materials were most likely obtained from the Nubian Desert and a nearby igneous formation.[6]

Axes

There were 48 stone axes found from a total of 26 graves. The axes could have been used as an adze, for butchering, or as weapons. The axes at R12 are highly variable in length, width, and thickness. Because axes were found in male, female, and child graves, it is hard to tell social context of the axes.[6]

Mace-heads

There were eight mace-heads were found at R12 within a total of seven graves. They were made from granite and pumice. The mace-heads made of pumice are the first ever found in Sudan. Six of the maces had a biconical shape, one had an ovoid shape, and one was disk-shaped with rising edges around the central hole. Mace-heads usually are a symbol of power. At R12, they only found in male and child graves. This possibly means that mace-heads have a social context and may only be associated with men or children.[6]

Stone palettes

There were 50 stone palettes found at R12 within a total of 27 graves. They were usually made from sandstone or granite. The red and yellow staining on the sandstone palettes indicates that they were probably used to grind red and yellow ochre to make pigments. Peoples of R12 most likely used these pigments on themselves and animals as well as on the surface of pottery. The granite palettes were used to grind malachite and amazonite which are assumed to be used as pigments. The three different classes of stone palettes are rectangular, ellipsoidal, and irregular. Stone palettes are evenly represented in male, female, and child graves.[6]

Grinding stones and grinders

Only a few grinding stones were found at R12 within a total of six graves, both male and female. The grinding stones were made from sandstone and limestone and were ovular in shape. They are thinner, lighter, and have finer surfaces than found at Mesolithic sites in Sudan.[6]

Grinders probably served the same purpose as palettes. They are made from sandstone and occasionally pumice. The grinders were rectangular, ellipsoidal, trapezoidal, or round. The small round grinders are also found in other Neolithic settlements in Sudan.[6]

Animal remains

Eighteen different mammal, bird, and mollusc taxa were found at R12. This large variety of animals is evidence that the people in the Nile river Valley used aquatic resources and hunted animals. Because these remains are found in a cemetery context, it is likely that the remains found are not representative of the living population at the time R12 was occupied. A likely reason that there is a large amount of cattle found at R12 is that cattle maintained a prestigious status in this area of Africa at the time.[8]

Mammals

Mammals found at R12 include bovids, cattle, sheep, goats, gazelles, monkeys, elephant, hippopotamus, and a dog/fox.[8]

Bovids

Bovid bones comprise a large amount of animal remains at R12. Because the bones were treated and turned into tools, it is hard to identify many of them taxonomically. However, the bones themselves are well preserved.[8]

Cattle are the most abundant taxon at R12. The remains are either cranial or postcranial bones. Fifty nine cattle skulls were analyzed from R12. Thirty one of the skulls could be identified as male while only two could be identified as female. Having more male cattle skulls shows the possibility of male cattle being symbols of prosperity, prestige, and power. Before being buried, the cattle show signs of being specially treated. The frontalia were cut off and cutting off the skin of the cattle left cut marks on the frontalia of many skulls. More than 40 cattle ribs were found across a total of 18 graves. All but three of the ribs were split longitudinally and the sides of the split were smoothed.[8]

A total of 21 sheep were found at R12. The most common bone from the sheep found was the tibia. Two complete sheep skeletons were found. Four tibiae of goats were found within a total of three graves. Three of the tibiae were formed into unfinished objects. One of the tibiae was formed into a spatula. There were many bones that could not be ascertained whether they belonged to goat or sheep.[8]

Birds

Birds found at R12 include ostrich, Helmeted Guinea fowl, and unidentified birds.[8]

Ostrich

Ostriches are the largest living bird in the world. Although many of the beads at R12 were created from ostrich eggshells, there is no evidence that ostrich themselves were located on or near the site. However, it is known that ostrich did live in this region of Africa. In general, ostrich bones are not well represented in the archaeological record. Ostrich most likely provided a variety of resources to the people of R12. Ostrich feathers were made into ornaments or fans. Ostrich eggs were used as food, vessels, and beads.[8]

Helmeted Guinea fowl

Today, the Guinea fowl family is local to Africa and the Arabian Peninsula. The Helmeted Guinea fowl are the most widespread of this species. There were three Helmeted Guinea fowl found at R12. There is no evidence that humans modified these bones, so their purpose is unknown.[8]

Molluscs

Molluscs found at R12 include bivalves and gastropods.[8]

Bivalves

There were 60 bivalve specimen were found throughout a total of 29 graves. A common bivalve found at R12 is the Nile oyster. These oysters are indicators of well-oxygenated and fast moving river water.[8]

Gastropods

There was one gastropod shell and many gastropod shell fragments found at R12. The gastropod species Limicolaria cailliaudi was not eaten and thus must likely have served a symbolic or ornamental function. The gastropod species Pila ovata and Pila wernei were most likely a source of food and possibly a protective charm against infertility and drowning. Other gastropod species were included in necklaces. Nerite gastropod shells were also found at R12. These shells are specifically interesting because they inhabit the Red Sea. This indicates that the people of R12 were utilizing trade routes.[8]

Archaeobotany

Plant remains at R12 mostly consist of grass inflorescence in the form of white powdery deposits.[9] These grasses are typically phytolith morphotypes of Panicoideae grasses. There are also trace amounts of an admixture of culms and leaves. The first samples of Hordeum sp. (cereal grains) and Triticum sp. (wheat) were found, making them the first sample of these genera at R12. Plant remains at R12 provide evidence for use of plants and argue against the view that there was only pastoralism in this area during the middle Neolithic.[1][10] Plant remains found at R12 predate the earliest Egyptian plant remains. Specifically, evidence of Triticeae predates evidence of farming in Egypt. This shows a possible earlier connection between regions in the Sahara Desert and southwest Asia than previously thought.[10] Based on this evidence and evidence from similar deposits at Ghaba, some suggest that domesticated cereals were introduced 500 years earlier than previously thought.[9] However, it is still unknown if many of these plants were grown locally or imported.[10]

Plant material found in graves at R12 give evidence of the importance of the role of plants in ritual burial.[9]

Social structure

The spatial distribution of R12 gives insight to the social structure of the people who created the cemetery. Within the cemetery, there is no segregation between males and females nor between adults and children. Because there is roughly and equal number of males and females it is possible that R12 was a non-polygamous society.[11]

Based on the artifacts found in the graves, the population has been split into three categories. The first category is people buried with no or few grave goods. This category comprises 68% of the population. Forty-three individuals buried at R12 have no grave goods. However, it is possible that erosion and human disturbances affected these graves, inflating the number of graves with no goods. The second category is people buried with a larger amount of grave goods. The third category is people buried with an even larger number of grave goods. As the number of objects in the grave increases, there are less graves. The third category comprises 20% of the population. The three categories could potentially signify a difference of wealth or rank. The distribution of objects, classes of objects, and presence and number of pottery are relatively the same. However, social status is explained more by amount of items rather than quality of items. This supports the idea that there were three segmented groups in the population based on wealth. Wealth seems to be distributed equally between males and females. Because children were found with grave goods, it is possible that status was ascribed and that there was family status. The children found with mace heads could signify a symbol of their family or lineage authority. Some grave goods such as animal remains, axes, and grinding stones could signify that the people of R12 were hunting. The lithic industry and plant remains could signify agricultural activities. Shells signify trade and contact with the Red Sea area. Cattle, sheep, and goat breeding were definitely a significant part of the society. This is known from animal remains and frequency of bucrania. Based on this evidence, it is likely that this was a pastoralist society that engaged in some hunting practices as well.[11]

Gebel Ramlah

Gebel Ramlah is a Neolithic site that is located in Egypt.[12] It is known for its six pastoral cemeteries including the world's oldest known infant cemetery.[13] Dental samples of people at Gebel Ramlah and people at R12 were compared to see if there was any biological relatedness between these two groups of people. Teeth from 59 individuals from Gebel Ramlah were examined. Teeth from 50 individuals from R12 were examined. Teeth from both sites ranged in quality from poor to fair. Each tooth was evaluated under 36 different traits. Based on the traits of the teeth, it was concluded that people from Gebel Ramlah and people from R12 were not closely biologically related.[14]

Even though there was no biological relation between these groups, they did share many cultural similarities. Objects found in graves at each site include pottery, ground stone, lithics, personal adornments, pigments, and animal remains. Both sites had similar pottery in the form of beakers. Even though there were these cultural similarities, there were also cultural differences. Bodies at Gebel Ramlah were placed on their right side in a flexed position, while bodies at R12 were placed on their left side.[14]

Climate

Today rainfall in the Dongola reach region of Sudan is an average of 23 mm a year, making the climate dry. While the site was active, the inter-tropical convergence zone was further north than where it is now. Because of this, there was more rainfall and the area experienced flooding from the Nile River. The rain and flooding allowed for the presence of vegetation, animals, and aquatic resources.[1]

References

- Out, Welmoed A.; Ryan, Philippa; García-Granero, Juan José; Barastegui, Judit; Maritan, Lara; Madella, Marco; Usai, Donatella (2016-08-15). "Plant exploitation in Neolithic Sudan: A review in the light of new data from the cemeteries R12 and Ghaba". Quaternary International. Southwest Asian domestic animals and plants in Africa:Routes, timing and cultural implications. 412: 36–53. Bibcode:2016QuInt.412...36O. doi:10.1016/j.quaint.2015.12.066. ISSN 1040-6182.

- Salvatori, Sandro. First season of excavation at site R12, a late Neolithic cemetery in the northern Dongola Reach. pp. 1–7. OCLC 615595009.

- Salvatori, Sandro (2008). A Neolithic Cemetery in the Northern Dongola Reach Excavations at Site R12. England: Archaeopress. pp. 9–19. ISBN 9781407303000.

- Salvatori, Sandro; Usai, Donatella (2008). A Neolithic Cemetery in the Northern Dongola Reach Excavations at Site R12. England: Archaeopress. pp. 21–31. ISBN 9781407303000.

- S. Salvatori, D. Usai, Y. Lecointe (2016). Ghaba An Early Neolithic Cemetery in Central Sudan. Africa Magna Verlag.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Usai, Donatella (2008). A Neolithic Cemetery in the Northern Dongola Reach Excavations at Site R12. England: Archaeopress. pp. 33–58. ISBN 9781407303000.

- Salvatori, Sandro; Usai, Donatella. The Second Excavation Season at R12, a Late Neolithic Cemetery in the Northern Dongola Reach.

- Pöllath, Nadja (2008). A Neolithic Cemetery in the Northern Dongola Reach Excavations at Site R12. England: Archaeopress. pp. 59–77. ISBN 9781407303000.

- Fernández, Víctor M.; Jimeno, Alfredo; Menéndez, Mario; Trancho, Gonzalo (1989-12-30). "The Neolithic site of Haj Yusif (Central Sudan)". Trabajos de Prehistoria. 46: 261–269. doi:10.3989/tp.1989.v46.i0.598. ISSN 1988-3218.

- Hildebrand, Elisabeth Anne; Schilling, Timothy M. (2016-08-15). "Storage amidst early agriculture along the Nile: Perspectives from Sai Island, Sudan". Quaternary International. Southwest Asian domestic animals and plants in Africa:Routes, timing and cultural implications. 412: 81–95. Bibcode:2016QuInt.412...81H. doi:10.1016/j.quaint.2016.01.057. ISSN 1040-6182.

- Salvatori, Sandro (2008). A Neolithic Cemetery in the Northern Dongola Reach Excavations at Site R12. England: Archaeopress. pp. 127–137. ISBN 9781407303000.

- Kobusiewicz, MichaƗ; Kabaciński, Jacek; Schild, Romuald; Irish, Joel D.; Wendorf, Fred (September 2004). "Discovery of the first Neolithic cemetery in Egypt's western desert". Antiquity. 78 (301): 566–578. doi:10.1017/S0003598X00113225. ISSN 0003-598X. S2CID 160244443.

- Czekaj-Zastawny, Agnieszka; Goslar, Tomasz; Irish, Joel D.; Kabaciński, Jacek (September 2018). "Gebel Ramlah—a Unique Newborns' Cemetery of the Neolithic Sahara". African Archaeological Review. 35 (3): 393–405. doi:10.1007/s10437-018-9307-1. ISSN 0263-0338.

- Irish, Joel D.; Bobrowski, Przemyslaw; Kobusiewicz, Michal; Kabaciski, Jacek; Schild, Romuald (2018-09-03). "An Artificial Human Tooth from the Neolithic Cemetery at Gebel Ramlah, Egypt". Dental Anthropology Journal. 17 (1): 28–31. doi:10.26575/daj.v17i1.142. ISSN 1096-9411.