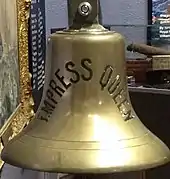

SS Empress Queen

SS Empress Queen was a steel-hulled paddle steamer, the last of her type ordered by the Isle of Man Steam Packet Company.[1] The Admiralty chartered her in 1915 as a troop ship a role in which she saw service until she ran aground off Bembridge, Isle of Wight, England in 1916 and was subsequently abandoned.

Empress Queen | |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name | Empress Queen |

| Namesake | Queen Victoria |

| Owner | IOMSPCo |

| Operator | IOMSPCo |

| Port of registry | Douglas |

| Builder | Fairfield Shipbuilding and Engineering Company, Govan |

| Cost | £130,000 |

| Yard number | 392 |

| Launched | 4 March 1897 |

| In service | 1897 |

| Identification |

|

| Fate | Grounded, abandoned and wrecked. |

| General characteristics | |

| Tonnage | 2,140 GRT, 914 NRT |

| Length | 360.1 ft (109.8 m) |

| Beam | 42.3 ft (12.9 m) |

| Depth | 17.0 ft (5.2 m) |

| Decks | 2 |

| Installed power | 10,000 ihp (7,500 kW), 1,290 NHP |

| Propulsion | 3-cylinder compound engines |

| Speed | 21.5 knots (39.8 km/h; 24.7 mph) |

| Capacity | 1,994 passengers |

| Crew | 95 |

Building and launch

The Fairfield Shipbuilding and Engineering Company in Govan, Glasgow built Empress Queen in 1897 at a cost of £130,000. Before her launch the directors of the Isle of Man Steam Packet Company issued a circular in which they invited the shareholders of the Company to decide on the name of the vessel. The choices offered were Empress Queen or Douglas. Empress Queen was chosen, in honour of Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee.

The decision did not meet with universal approval; the Isle of Man Times of Tuesday January 19, 1897, disregarding sentiment and citing practicality, stated in an editorial that it thought it better to use the name Douglas, as it would be more easily recognised by passengers.[2] In addition it was leveled that the decision had been taken by English shareholders, who formed the majority of the Company's shareholding.[3] With the decision on the vessel's name decided, the launch date was initially fixed for February 18, 1897 – the christening ceremony to be performed by Mrs Margaret Mylrea, wife of Chairman of the Isle of Man Steam Packet Company, John Allen Mylrea.[4][5][6]

The launch had to be delayed when a fire broke out in Fairfield's yards in February 1897. The fire caused major damage to the yard and threatened the cruiser HMS Argonaut at that time on the stocks under construction, as well as various other vessels including the Empress Queen. However, due to the vessels being separated from the buildings no damage was sustained.[7][8] Consequently, the launch was rescheduled.[8]

Empress Queen was successfully launched at 13:00hrs on Thursday March 4, 1897.[9][10] A large delegation of directors and officials from the Isle of Man Steam Packet Company were present, along with Sir William Pearce, Chairman of Fairfield Shipbuilding and Engineering Company, Admiralty representatives and visitors from Liverpool, Edinburgh and Glasgow.[6]

Dimensions and layout

Empress Queen was the largest and fastest paddle-driven cross-channel steamship ever built. Her tonnage was 2,140 GRT; registered length 360.1 ft (109.8 m), beam 42.3 ft (12.9 m), depth 17.0 ft (5.2 m). The engine design was very advanced for its day. The machinery consisted of two diagonal surface condensing engines. There were three steam cylinders placed side by side, working on three cranks; the high pressure cylinder being situated between the two low pressure cylinders.[6] The high pressure cylinder was fitted with a piston valve and each of the low pressure cylinders with flat slide valves, which were controlled by double eccentrics and link motion valve gear. The starting and reversing was achieved by a large steam and hydraulic engine constructed on the direct acting principle.

The high pressure cylinder was 68 inches in diameter with the two low-pressure cylinders 92 inches in diameter. The stroke was 84 inches and the usual running speed was 44 rpm.[6]

The condenser was cylindrical and placed athwartships between the cylinders and the supports for the shafting, while the condensing water was supplied by a separate circulating pump, worked by an independent engine.[6]

The paddle wheels were constructed of steel on the feathering principle with curved floats.[6] Steam was supplied to the engines from four double-ended boilers, producing a boiler steam pressure of 140 pounds per square inch (970 kPa) arranged in two compartments, one forward and one aft of the engine room. The boilers were of the multitubular return marine type, each having eight corrugated furnaces being constructed entirely of steel to Board of Trade requirements and working on a system of forced draught with fans fitted to supply air. Sixteen firemen worked at her 32 furnaces.[6]

The engines developed 10,000 ihp (this compared to the 6,500 ihp developed by the Queen Victoria and Prince of Wales and 4,500 ihp in the Mona's Isle) and produced to give Empress Queen a service speed of 21.5 knots (39.8 km/h; 24.7 mph). Her boilers and engines also came from her builder.[6]

At the time, her engines and paddle wheels were claimed to be the heaviest ever placed in a cross-channel paddle steamer, with one paddle shaft wheel alone weighing 70 tons.[6]

In order to facilitate better handling in port, Empress Queen was fitted with a bow rudder in addition to the stern rudder.[6] The hull was divided into several watertight compartments by means of steel transverse bulkheads which additionally augmented the strength of the hull forming supports and ties between the decks and framing. A steam capstan windlass was fitted forward for working the ship's cables, and on the spar deck there was a steam capstan for warping and mooring purposes. Situated forward was a double acting steam winch which was used for the loading and unloading of luggage.[6]

Appearance

Empress Queen's design and layout was suited to the late Victorian era. She was a full poop vessel, consisting of four decks:

- Lower deck

- Main deck

- Bridge deck

- Promenade deck

[6] Dining accommodation for 124 first class passengers was provided in a handsomely furnished saloon on the lower deck, with pantry, scullery and bar adjacent. The dining saloon ahead of the machinery on the lower deck could accommodate 130 second class passengers whose quarters were in the forward part of the vessel.[6] The ladies second class saloon was also on the lower deck. The main deck was arranged as a second class shelter, and contained a bar and buffet. The galley, which prepared food for all passengers was situated aft of the boiler room. All the saloons and cabins were panelled, upholstered, carpeted and curtained.[6]

A general saloon was situated on the main deck, 98 ft (30 m) x 40 ft (12 m), which was capable of holding 700 people, forward of which was the ladies boudoir. On the lower deck there was another general saloon 60 ft (18 m) x 35 ft (11 m) with berth accommodation.[6]

On the bridge deck there were situated 10 State Rooms, forward of this was situated a smoke room for the cabin passengers.[6] A new feature for ships of the Isle of Man Steam Packet was the promenade (or flying deck) which was used as a promenade by saloon passengers and extended from forward of the boiler room to aft of the first class cabins.[6] Buoyant seats ran practically the full length of the deck, except for the after part of the deck which was required for the ship's lifeboats. Altogether the promenade deck covered three quarters of the length and the whole breadth of the ship.[6]

The bridges which surmounted the promenade deck were placed, one at the forward extremity, for navigating purposes, and the other between the funnels.[6] The second extended from sponson to sponson and beneath which was situated the Captain's cabin. The arrangement was designed to offer better handling of the vessel when docking. From both bridges the bow and stern rudders were controlled by means of wheels connected with independent steam steering gears, placed below, on the engine starting platform. A hand screw steering apparatus was placed in reserve aft, for use in an emergency.[6]

A complete installation of electric lighting was fitted throughout, including deck and embarkation lights.[6]

Mail and cargo

Empress Queen was designed primarily for the carriage of passengers, but she could also accommodate a quantity of cargo. Her designation as a Royal Mail Ship (RMS) indicated that she carried mail under contract with the Royal Mail. Situated on the main deck was a specified area, allocated for the storage of letters, parcels and specie (bullion, coins and other valuables).[6]

Civilian service

Entering service under Captain Alexander McQueen, Commodore of the Company, she was the first Steam Packet vessel to be fitted with wireless telegraphy, which was installed on 19 August 1903.[6]

Empress Queen was the last paddle steamer ordered to be built for the line, and she was a record breaker for her day. On 13 September 1897 she made passage from the Rock Lighthouse, New Brighton, to Douglas Head (a distance of 68 nautical miles), in 2 hr. 57 min.; the fastest time then recorded. The whole voyage from the Princes Landing Stage to Douglas Harbour took three hours and five minutes, two minutes faster than the record held by the Prince of Wales.[11]

She continued to operate to and from the Island until the Admiralty chartered her on 6 February 1915.

War service and loss

Empress Queen was ideal as a troop carrier. On leaving Douglas she steamed to Barrow and was fitted out for her wartime role in less than two weeks. Following her fitting out, she then made passage to Southampton and two days later was on the first of her duties, taking 1,900 men of a Scottish regiment to Le Havre.

Empress Queen was widely regarded by the authorities as an exceptionally reliable paddle steamer; she had never stopped for weather or engine trouble. However, on 1 February 1916, whilst returning to Southampton from Le Havre with 1,300 men on board, she ran ashore at 05:00hrs on the Ring Rocks off Bembridge, Isle of Wight, running high onto the rocks on a rising tide. At the time of the grounding the wind was light, and the sea state was calm.

Destroyers took off the troops, however the crew remained on board as efforts were made to refloat the vessel. It was not expected to be a difficult task, but it proved impossible. The weather changed in a matter of hours and a gale blew up. The Queen Victoria was launched from the Bembridge Lifeboat Station to undertake rescue operations.

Coxswain John Holbrook injured his hand while fastening a line to the stricken vessel, but nevertheless made four trips between the ship and the shore, rescuing 110 people. And additional nine people were rescued by another vessel. Holbrook was awarded an RNLI silver medal for his actions.[12][13]

Wind and waves broke up Empress Queen as the seasons passed. She became a familiar landmark to Southampton and Portsmouth shipping. Her two funnels were still visible above water on Armistice Day. In the following summer, after a long and heavy gale, they finally disappeared.

The position of the wreck of Empress Queen is given as 50°40′0″N 1°05′0″W.[14]

References

- "The Empress Queen". isleofman.com. Retrieved 15 April 2012.

- Isle of Man Times, Tuesday, January 19, 1897; Page: 2

- Isle of Man Times, Saturday, January 23, 1897; Page: 11

- Manx Sun, Saturday, January 30, 1897; Page: 5

- Isle of Man Examiner, Saturday, January 30, 1897; Page: 5

- Isle of Man Times, Saturday, March 06, 1897; Page: 4

- Isle of Man Times, Saturday, February 13, 1897; Page: 5

- Isle of Man Times, Tuesday, February 09, 1897; Page: 12

- "Launches and Trial Trips: Launches—Scotch: Empress Queen". The Marine Engineer. 1 April 1897. p. 30.

- "Empress Queen". Scottish Built Ships. Caledonian Maritime Research Trust. Retrieved 1 September 2022.

- Henry 1962, p. 19.

- Leach 1999, p. 78.

- Cox 1998, p. 236.

- "PSS Empress Queen [+1916]". wrecksite.eu. 1 February 2014.

Bibliography

- Chappell, Connery (1980). Island Lifeline. T. Stephenson & Sons Ltd. ISBN 0-901314-20-X.

- Cox, Barry (1998). Lifeboat Gallantry – RNLI Medals and how they were won. Spink & Son Ltd. ISBN 0907605893.

- Henry, Fred (1962). Ships of the Isle of Man Steam Packet Company. Glasgow: Brown, Son & Ferguson.

- Leach, Nicholas (1999). For Those In Peril – The Lifeboat Service of the United Kingdom and the Republic of Ireland, Station by Station. Vol. Part 2, South Coast of England – Eastbourne to Weston-super-Mare. Silver Link Publishing Ltd. ISBN 1-85794-129-2.

External links

Media related to Empress Queen at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Empress Queen at Wikimedia Commons