Phytophthora

Phytophthora (from Greek φυτόν (phytón), "plant" and φθορά (phthorá), "destruction"; "the plant-destroyer") is a genus of plant-damaging oomycetes (water molds), whose member species are capable of causing enormous economic losses on crops worldwide, as well as environmental damage in natural ecosystems. The cell wall of Phytophthora is made up of cellulose. The genus was first described by Heinrich Anton de Bary in 1875. Approximately 210 species have been described, although 100–500 undiscovered Phytophthora species are estimated to exist.[2]

| Phytophthora | |

|---|---|

| |

| Phytophthora porri on leek (Allium porrum) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Chromista |

| Phylum: | Oomycota |

| Order: | Peronosporales |

| Family: | Peronosporaceae |

| Genus: | Phytophthora de Bary 1876[1] |

| Species | |

Pathogenicity

Phytophthora spp. are mostly pathogens of dicotyledons, and many are relatively host-specific parasites. Phytophthora cinnamomi, though, infects thousands of species ranging from club mosses, ferns, cycads, conifers, grasses, lilies, to members of many dicotyledonous families. Many species of Phytophthora are plant pathogens of considerable economic importance. Phytophthora infestans was the infective agent of the potato blight that caused the Great Famine of Ireland, and still remains the most destructive pathogen of solanaceous crops, including tomato and potato.[3] The soya bean root and stem rot agent, Phytophthora sojae, has also caused longstanding problems for the agricultural industry. In general, plant diseases caused by this genus are difficult to control chemically, thus the growth of resistant cultivars is the main management strategy. Other important Phytophthora diseases are:

- Phytophthora agathidicida—causes collar-rot on New Zealand kauri (Agathis australis), New Zealand's most voluminous tree, an otherwise successful survivor of the Jurassic

- Phytophthora cactorum—causes rhododendron root rot affecting rhododendrons, azaleas, and orchids, and causes bleeding canker in hardwood trees

- Phytophthora capsici—infects Cucurbitaceae fruits, such as cucumbers and squash

- Phytophthora cinnamomi—causes cinnamon root rot affecting forest and fruit trees, and woody ornamentals including arborvitaee, azalea, Chamaecyparis, dogwood, forsythia, Fraser fir, hemlock, Japanese holly, juniper, Pieris, rhododendron, Taxus, white pine, American chestnut and Australian woody plants, especially eucalypt and banksia.

- Phytophthora citricola—causes root rot and stem cankers in citrus trees

- Phytophthora fragariae—causes red root rot affecting strawberries

- Phytophthora infestans causes the serious disease known as potato (late) blight: responsible for the Great Famine of Ireland.

- Phytophthora kernoviae—pathogen of beech and rhododendron, also occurring on other trees and shrubs including oak, and holm oak. First seen in Cornwall, UK, in 2003.[4]

- Phytophthora lateralis—causes cedar root disease in Port Orford cedar trees

- Phytophthora megakarya—one of the cocoa black pod disease species, is invasive and probably responsible for the greatest cocoa crop loss in Africa

- Phytophthora multivora—discovered in analysis of isolates with P. cinnamomi dieback infections of tuart forests of Southwest Australia, which were previously diagnosed as P. citricola. The species was found occurring on many other taxa, so named multivora.[5]

- Phytophthora nicotianae—infects tobacco and onions

- Phytophthora palmivora—causes fruit rot in coconuts and betel nuts

- Phytophthora ramorum—infects over 60 plant genera and over 100 host species; causes sudden oak death[6]

- Phytophthora quercina—causes oak death

- Phytophthora sojae—causes soybean root rot

Research beginning in the 1990s has placed some of the responsibility for European forest die-back on the activity of imported Asian Phytophthoras.[7]

In 2019, scientists in Connecticut were conducting experiments testing various methods to grow healthier Fraser trees when they accidentally discovered a new species of Phytophthora, which they called Phytophthora abietivora. The fact that these scientists so readily discovered a new species further suggests that there could be many more species waiting to be discovered.[8]

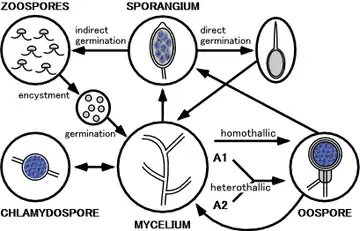

Reproduction

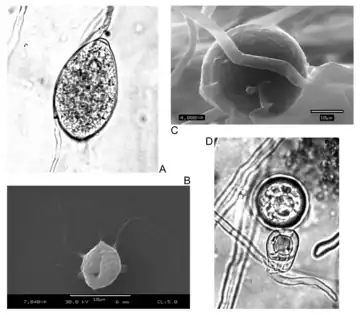

Phytophthora species may reproduce sexually or asexually. In many species, sexual structures have never been observed, or have only been observed in laboratory matings. In homothallic species, sexual structures occur in single culture. Heterothallic species have mating strains, designated as A1 and A2. When mated, antheridia introduce gametes into oogonia, either by the oogonium passing through the antheridium (amphigyny) or by the antheridium attaching to the proximal (lower) half of the oogonium (paragyny), and the union producing oospores. Like animals, but not like most true fungi, meiosis is gametic, and somatic nuclei are diploid. Asexual (mitotic) spore types are chlamydospores, and sporangia which produce zoospores. Chlamydospores are usually spherical and pigmented, and may have a thickened cell wall to aid in their role as a survival structure. Sporangia may be retained by the subtending hyphae (noncaducous) or be shed readily by wind or water tension (caducous) acting as dispersal structures. Also, sporangia may release zoospores, which have two unlike flagella which they use to swim towards a host plant.

Zoospores (and zoospores of Pythium, also in the Peronosporales) recognize not only hosts but particular locations on hosts.[9] Phytophthora zoospores recognize and attach to specific root surface regions.[9] This is a high degree of specificity at an early stage of cell development.[9]

Evolution and resemblance to fungi

Phytophthora is sometimes referred to as a fungus-like organism, but it is classified under a different clade altogether: SAR supergroup (Harosa) (also under Stramenopila and previously under Chromista). This is a good example of convergent evolution: Phytophthora is morphologically very similar to true fungi yet its evolutionary history is completely distinct. In contrast to fungi, SAR supergroup is more closely related to plants than to animals. Whereas fungal cell walls are made primarily of chitin, Phytophthora cell walls are constructed mostly of cellulose. Ploidy levels are different between these two groups; Phytophthora species have diploid (paired) chromosomes in the vegetative (growing, nonreproductive) stage of life, whereas fungi are almost always haploid in this stage. Biochemical pathways also differ, notably the highly conserved lysine synthesis path.

Species

The NCBI lists:[10]

- Phytophthora acerina

- Phytophthora afrocarpa

- Phytophthora agathidicida

- Phytophthora aleatoria[11]

- Phytophthora alni

- Phytophthora × alni

- Phytophthora alpina [12]

- Phytophthora alticola

- Phytophthora amaranthi

- Phytophthora amnicola

- Phytophthora amnicola × moyootj

- Phytophthora xandina

- Phytophthora aquimorbida

- Phytophthora arecae

- Phytophthora arenaria

- Phytophthora cf. arenaria

- Phytophthora aff. arenaria

- Phytophthora asiatica

- Phytophthora asparagi

- Phytophthora aff. asparagi

- Phytophthora attenuata

- Phytophthora austrocedrae

- Phytophthora balyanboodja

- Phytophthora batemanensis syn. Halophytophthora batemanensis

Phytophthora betacei

- Phytophthora bilorbang

- Phytophthora bishii

- Phytophthora boehmeriae

- Phytophthora boodjera

- Phytophthora borealis

- Phytophthora botryosa

- Phytophthora cf. botryosa

- Phytophthora aff. botryosa

- Phytophthora brassicae

- Phytophthora cactorum

- Phytophthora cactorum × hedraiandra

- Phytophthora cajani

- Phytophthora × cambivora

- Phytophthora capensis

- Phytophthora capsici

- Phytophthora aff. capsici

- Phytophthora captiosa

- Phytophthora castaneae

- Phytophthora castanetorum

- Phytophthora chesapeakensis [13][14]

- Phytophthora chlamydospora

- Phytophthora chrysanthemi

- Phytophthora cichorii

- Phytophthora aff. cichorii

- Phytophthora cinnamomi

- Phytophthora cinnamomi var. cinnamomi

- Phytophthora cinnamomi var. parvispora

- Phytophthora cinnamomi var. robiniae

- Phytophthora citricola

- Phytophthora aff. citricola

- Phytophthora citrophthora

- Phytophthora citrophthora var. clementina

- Phytophthora aff. citrophthora

- Phytophthora clandestina

- Phytophthora cocois

- Phytophthora colocasiae

- Phytophthora condilina

- Phytophthora constricta

- Phytophthora cooljarloo

- Phytophthora crassamura

- Phytophthora cryptogea

- Phytophthora aff. cryptogea

- Phytophthora cuyabensis

- Phytophthora cyperi

- Phytophthora dauci

- Phytophthora aff. dauci

- Phytophthora drechsleri

- Phytophthora drechsleri var. cajani

- Phytophthora elongata

- Phytophthora cf. elongata

- Phytophthora erythroseptica

- Phytophthora erythroseptica var. pisi

- Phytophthora aff. erythroseptica

- Phytophthora estuarina

- Phytophthora europaea

- Phytophthora fallax

- Phytophthora flexuosa

- Phytophthora fluvialis

- Phytophthora fluvialis × moyootj

- Phytophthora foliorum

- Phytophthora formosa

- Phytophthora formosana

- Phytophthora fragariae

- Phytophthora fragariaefolia

- Phytophthora frigida

- Phytophthora gallica

- Phytophthora gemini

- Phytophthora gibbosa

- Phytophthora glovera

- Phytophthora gonapodyides

- Phytophthora gondwanensis

- Phytophthora gregata

- Phytophthora cf. gregata

- Phytophthora hedraiandra

- Phytophthora aff. hedraiandra

- Phytophthora × heterohybrida

- Phytophthora heveae

- Phytophthora hibernalis

- Phytophthora himalayensis

- Phytophthora himalsilva

- Phytophthora aff. himalsilva

- Phytophthora humicola

- Phytophthora aff. humicola

- Phytophthora hydrogena

- Phytophthora hydropathica [15]

- Phytophthora idaei

- Phytophthora ilicis

- Phytophthora × incrassata

- Phytophthora infestans

- Phytophthora aff. infestans

- Phytophthora inflata

- Phytophthora insolita

- Phytophthora cf. insolita

- Phytophthora intercalaris

- Phytophthora intricata

- Phytophthora inundata

- Phytophthora ipomoeae

- Phytophthora iranica

- Phytophthora irrigata [15]

- Phytophthora katsurae

- Phytophthora kelmania

- Phytophthora kernoviae

- Phytophthora kwongonina

- Phytophthora lactucae

- Phytophthora lacustris

- Phytophthora lacustris × riparia

- Phytophthora lateralis

- Phytophthora lilii

- Phytophthora litchii

- Phytophthora litoralis

- Phytophthora litoralis × moyootj

- Phytophthora macilentosa

- Phytophthora macrochlamydospora

- Phytophthora meadii

- Phytophthora aff. meadii

- Phytophthora medicaginis

- Phytophthora medicaginis × cryptogea

- Phytophthora mediterranea

- Phytophthora megakarya

- Phytophthora megasperma

- Phytophthora melonis

- Phytophthora mengei

- Phytophthora mexicana

- Phytophthora cf. mexicana

- Phytophthora mirabilis

- Phytophthora mississippiae

- Phytophthora morindae

- Phytophthora moyootj

- Phytophthora moyootj × fluvialis

- Phytophthora moyootj × litoralis

- Phytophthora moyootj × thermophila

- Phytophthora × multiformis

- Phytophthora multivesiculata

- Phytophthora multivora

- Phytophthora nagaii

- Phytophthora nemorosa [16]

- Phytophthora nicotianae

- Phytophthora nicotianae × cactorum

- Phytophthora niederhauserii

- Phytophthora cf. niederhauserii

- Phytophthora obscura

- Phytophthora occultans

- Phytophthora oleae

- Phytophthora ornamentata

- Phytophthora pachypleura

- Phytophthora palmivora

- Phytophthora palmivora var. palmivora

- Phytophthora parasitica

- Phytophthora parasitica var. nicotianae

- Phytophthora parasitica var. piperina

- Phytophthora parsiana

- Phytophthora aff. parsiana

- Phytophthora parvispora

- Phytophthora × pelgrandis

- Phytophthora phaseoli

- Phytophthora pini

- Phytophthora pinifolia

- Phytophthora pisi

- Phytophthora pistaciae

- Phytophthora plurivora

- Phytophthora pluvialis

- Phytophthora polonica

- Phytophthora porri

- Phytophthora primulae

- Phytophthora aff. primulae

- Phytophthora pseudocryptogea

- Phytophthora pseudolactucae

- Phytophthora pseudorosacearum

- Phytophthora pseudosyringae

- Phytophthora pseudotsugae

- Phytophthora aff. pseudotsugae

- Phytophthora psychrophila

- Phytophthora quercetorum

- Phytophthora quercina

- Phytophthora quininea

- Phytophthora ramorum

- Phytophthora rhizophorae

- Phytophthora richardiae

- Phytophthora riparia

- Phytophthora rosacearum

- Phytophthora aff. rosacearum

- Phytophthora rubi

- Phytophthora sansomea

- Phytophthora sansomeana

- Phytophthora aff. sansomeana

- Phytophthora × serendipita

- Phytophthora sinensis

- Phytophthora siskiyouensis

- Phytophthora sojae

- Phytophthora stricta

- Phytophthora sulawesiensis

- Phytophthora syringae

- Phytophthora tabaci

- Phytophthora tentaculata

- Phytophthora terminalis

- Phytophthora thermophila

- Phytophthora thermophila × amnicola

- Phytophthora thermophila × moyootj

- Phytophthora tonkinensis

- Phytophthora trifolii

- Phytophthora tropicalis

- Phytophthora cf. tropicalis

- Phytophthora tubulina

- Phytophthora tyrrhenica

- Phytophthora uliginosa

- Phytophthora undulata

- Phytophthora uniformis

- Phytophthora vignae

- Phytophthora vignae f. sp. adzukicola

- Phytophthora virginiana

- Phytophthora vulcanica

References

- Heinrich Anton de Bary, Journal of the Royal Agricultural Society of England, ser. 2 12: 240 (1876)

- Brasier CM, 2009. Phytophthora biodiversity: how many Phytophthora species are there? In: Goheen EM, Frankel SJ, eds. Phytophthoras in Forests and Natural Ecosystems. Albany, CA, USA: USDA Forest Service: General Technical Report PSW-GTR-221, 101–15.

- Nowicki, Marcin; et al. (17 August 2011), "Potato and tomato late blight caused by Phytophthora infestans: An overview of pathology and resistance breeding", Plant Disease, 96 (1): 4–17, doi:10.1094/PDIS-05-11-0458, PMID 30731850

- Brasier, C; Beales, PA; Kirk, SA; Denman, S; Rose, J (2005). "Phytophthora kernoviae sp. Nov., an invasive pathogen causing bleeding stem lesions on forest trees and foliar necrosis of ornamentals in the UK" (PDF). Mycological Research. 109 (Pt 8): 853–9. doi:10.1017/S0953756205003357. PMID 16175787. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-03-15. Retrieved 2009-03-04.

- Scott, PM; Burgess, TI; Barber, PA; Shearer, BL; Stukely, MJ; Hardy, GE; Jung, T (June 2009). "Phytophthora multivora sp. nov., a new species recovered from declining Eucalyptus, Banksia, Agonis and other plant species in Western Australia". Persoonia. 22: 1–13. doi:10.3767/003158509X415450. PMC 2789538. PMID 20198133.

- "APHIS List of Regulated Hosts and Plants Associated with Phytophthora ramorum" U.S. Animal and Plant Health Inspection Services Archived 2006-12-12 at the Wayback Machine;

- "Phytophthora: Asiatischer Pilz lässt die Bäume sterben" Süddeutschen Zeitung 11 May 2005

- Li, DeWei; Schultes, Neil; LaMondia, James; Cowles, Richard (2019). "Phytophthora abietivora, A New Species Isolated from Diseased Christmas Trees in Connecticut, U.S.A." Plant Disease. American Phytopathological Society. 103 (12): 3057–3064. doi:10.1094/PDIS-03-19-0583-RE. PMID 31596694.

- Nicholson, Ralph L.; Epstein, Lynn (1991). "Adhesion of Fungi to the Plant Surface". In Cole, Garry T.; Hoch, Harvey C. (eds.). The Fungal Spore and Disease Initiation in Plants and Animals. Boston, Ma, USA. pp. 3–23/xxv+555. doi:10.1007/978-1-4899-2635-7_1. ISBN 978-1-4899-2635-7. OCLC 913636088. S2CID 82631781. ISBN 978-0-306-43454-9. ISBN 978-1-4899-2637-1.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - "Phytophthora". NCBI taxonomy. Bethesda, MD: National Center for Biotechnology Information. Retrieved 18 June 2018.

- Scott P, Taylor P, Gardner J, Puértolas A, Panda P, Addison S, Hood I, Burgess T, Horner I, Williams N, McDougal R (2019). "Phytophthora aleatoria sp. nov., associated with root and collar damage on Pinus radiata from nurseries and plantations". Australasian Plant Pathology. 48 (4): 313–321. doi:10.1079/cabicompendium.50755878. S2CID 253910078.

- Template:Cote journal

- "Taxonomy browser (Phytophthora chesapeakensis)". National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI). Retrieved 2023-02-28.

- Man in 't Veld, W.A. et al. 2019. Multiple Halophytophthora spp. and Phytophthora spp. including P. gemini, P. inundata and P. chesapeakensis sp. nov. isolated from the seagrass Zostera marina in the Northern hemisphere. Eur J Plant Pathol 153: 341-357. doi:10.1007/s10658-018-1561-1

- Hong, C; Gallegly, M; Richardson, P; Kong, P; Moorman, G; Lea-Cox, J; Ross, D (June 2008). "Phytophthora irrigata and Phytophthora hydropathica, two new species from irrigation water at ornamental plant nurseries". Phytopathology Vol. 98, no. 6. Archived from the original on 2012-03-07. Retrieved 2016-10-10.

- Hansen, Everett M.; Reeser, P. W.; Davidson, J. M.; Garbelotto, Matteo; Ivors, K.; Douhan, L.; Rizzo, David M. (2003). "Phytophthora nemorosa, a new species causing cankers and leaf blight of forest trees in California and Oregon, U.S.A" (PDF). Mycotaxon. 88: 129–138.

- "Phytophthora nicotianae var. parasitica (PHYTNP)[Overview]". Global Database. EPPO (European and Mediterranean Plant Protection Organization). 2002. Retrieved 2023-03-06.

Sanna GP, Bottos A, Maddau L, Montecchio L, Linaldeddu BT. 2020.Diversity and pathogenicity of Phytophthora species associated with declining alder trees in Italy and description of Phytophthora alpina sp. nov. Forests 11 (8): 848

Further reading

- Lucas, J.A. et al. (eds.) (1991) Phytophthora based on a symposium held at Trinity College, Dublin, Ireland September 1989. British Mycological Society, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK, ISBN 0-521-40080-5;

- Erwin, Donald C. and Ribeiro, Olaf K. (1996) Phytophthora Diseases Worldwide American Phytopathological Society Press, St. Paul, Minnesota, ISBN 0-89054-212-0

- Erwin, Donald C. (1983) Phytophthora: its biology, taxonomy, ecology, and pathology American Phytopathological Society Press, St. Paul, Minnesota, ISBN 0-89054-050-0

- "APHIS List of Regulated Hosts and Plants Associated with Phytophthora ramorum" U.S. Animal and Plant Health Inspection Services

- "Dieback" Department of Environment and Conservation, Western Australia

- Lamour, Kurt (2013). Lamour, K. (ed.). Phytophthora: A Global Perspective. CABI Plant Protection Series. CABI (Centre for Agriculture and Bioscience International). pp. xi+244. doi:10.1079/9781780640938.0000. ISBN 9781780640938. LCCN 2012042152. 978-1-78064-093-8.

External links

- Goodwin, Stephen B. (January 2001) "Phytophthora Bibliography" Purdue University

- Abbey, Tim (2005) "Phytophthora Dieback and Root Rot" College of Agriculture and Natural Resources, University of Connecticut

- "Phytophthora Canker – Identification, Biology and Management" Bartlett Tree Experts Online Resource Library

- "Phytophthora Root Rot – Identification, Biology and Management" Bartlett Tree Experts Online Resource Library

- Dieback Working Group – Western Australia