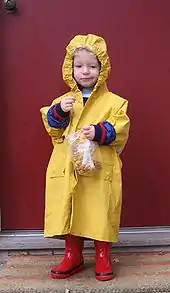

Raincoat

A raincoat is a waterproof or water-resistant garment worn on the upper body to shield the wearer from rain. The term rain jacket is sometimes used to refer to raincoats with long sleeves that are waist-length. A rain jacket may be combined with a pair of rain pants to make a rainsuit. Rain clothing may also be in one piece, like a boilersuit. Raincoats, like rain ponchos, offer the wearer hands-free protection from the rain and elements; unlike the umbrella.

Modern raincoats are often constructed from waterproof fabrics that are breathable, such as Gore-Tex or Tyvek and DWR-coated nylon. These fabrics and membranes allow water vapor to pass through, allowing the garment to 'breathe' so that the sweat of the wearer can escape. The amount of pouring rain a raincoat can handle is sometimes measured in the unit millimeters, water gauge.

Early history

One of oldest examples of rainwear recorded is likely the woven grass cape/mat of Ötzi, around 3230 BCE.

The Olmec Native Americans first invented rubber sometime before 1600 BCE. They developed methods to extract natural latex resin from the rubber tree (Hevea brasiliensis), and cure the latex resin into stabilized rubber using the sulfuric compounds of the morning glory in order to create some of the world's first waterproof textile fabrics using cotton and other plant fibers. These rubberized fabrics were crafted into waterproof cloaks, direct precursors to the modern raincoat, as well as other waterproof clothing like shoes.

The indigenous peoples of the Northwest Pacific Coast wore raincoats and other clothing made of woven cedar fiber which, depending on the tightness of the weave, could be dense and watertight, or soft and comfortable.

Throughout much of Eastern and Midwestern regions of North America, many Native American nations used treated leather from a variety of animals to create waterproof clothes, sometimes covered in fringe, to stay warm and dry. In addition to the decorative function, fringe would pull water off the main portion of their clothes so that the garment dried quicker.[1]

The particularities of the Arctic climate gave rise to a distinctive culture of waterproof clothing. The Inuit, Aleuts, and many other peoples in the Arctic region have traditionally worn shirts, coats, and parkas made from the skins of seal, sea otter, fish, and birds. Birdskin shirts, with the feathers on the outside, provide excellent protection from rain as they repel moisture. In Aleut culture, a kamleika is worn as the outermost garment on top of the parka when necessary.[2]

In East Asian cultures such as Vietnam, China, the Korean Peninsula, and Japan, the use of naturally water-repellent plant fibers, such as rice straw, to create waterproof raincoats and cloaks has been known since ancient times. This raincoat style often consisted of both an upper rainjacket and a lower apron. Materials varied, and were usually locally sourced. Each set took two to three days to craft and was typically paired with a matching straw hat. Raindrops that fell on such garments would run along the fibers and not penetrate into the interior, keeping the wearer dry. They were a common sight among farmers and fishermen on rainy and snowy days, as well as travelers during the rainy season. The raincoat being an absolutely indispensable asset, famed writer Xu Guangqi recorded a popular proverb during the Ming: "No raincoat, no going out."[3] When hunting or traveling at night, the coat could be used as a sleeping pad, and the smell of the leaves would drive away insects and snakes. When worn in wetlands or forests, these cloaks often blended in with the surrounding landscape, making the wearer more difficult to see. As garments made with pre-modern technology, they were extremely waterproof and breathable, but also bulky, and vulnerable to fire. While no longer used as raingear in modern times, traditional straw raincoats are still being made for special purposes such as religious events, tourist souvenirs, and interior decorations.[4]

During the Zhou dynasty in China, the main materials for making raincoats and capes was rice straw, sedge, burlap, and coir. In southern China, hydrangeas were also used. Since at least 200 BCE, lightweight silk hanfu were rubbed with vegetable oils such as Tung oil to repel the rain. During the Ming dynasty, wealthy men and women could wear a “jade needle cape” made of Chinese silvergrass, considered soft and waterproof. During the Qing dynasty, emperors and officials wore raincoats made out of the pipal tree. Yellow garments were for the exclusive use of the emperor, red ones for princes and the highest court officials, and cyan ones for the second-ranking officials. Raincoats were made out of felt for winter use, with sateen and camlet for spring through autumn.[5]

Rain capes made of straw have many indigenous names in modern Mexico, but they are most well known as capotes de plumas (also chereque, cherépara, or chiripe) as they are known in Michoacan and the capisallo from Tlaxcala, so named for the palm leaves' resemblance to bird feathers. In some regions, such as Colima, these rain capes are called china de palma trenzada because of their presumed Filipino origins. These capes can still be found today, in the most traditional indigenous corners of the country.

In New Zealand, the pākē or hieke are made from New Zealand Flax. In Polynesian Hawaii, Kui la’i or Ahu La`i are made from the leaves of the Ti plant, used not only to protect people from the rain, but also from the sun in hotter parts of the islands. Fishermen would wear them for protection from foul weather and ocean spray, similar in purpose to oilskins.

Furs were popular rainwear in Europe for much of its history, although the modest means of peasants and poor laborers limited the fur to cheaper varieties of goat or cat. Eventually, wool rainwear replaced fur as popular attitudes changed in the later Medieval period. Wool was known for its ability to keep the wearer warm even when soaked, especially wool that had been fulled during the manufacturing process. If wool was made without stringent cleaning, it would retain some of the sheep's lanolin and be naturally somewhat water-resistant although not fully waterproof. Waxing of garments was known in England, but seldom done elsewhere due to the scarcity and expense of wax.[6]

In the 15th and 16th century CE, Europeans arriving to the Americas recorded for themselves that the indigenous peoples of Mesoamerica and the Amazon basin had created waterproof rubber-impregnated fabrics, although the Native American procedure of curing rubber was not well conveyed to them, and the tropical rubber tree did not grow well in the colder climates of Europe. As a result, rubber remained an impractical curiosity to Europeans until their redevelopment of the vulcanization process about 300 years later.[7][8][9]

Modern developments

One of the first modern waterproof raincoats was created following the patent by Scottish chemist Charles Macintosh in 1824 of new tarpaulin fabric, described by him as "India rubber cloth," and made by sandwiching a core of rubber softened by naphtha between two pieces of fabric.[10][11] The Mackintosh raincoat was made out of a fabric impregnated with impermeable rubber, although lacking the better curing methods of earlier Mesoamerican rainwear, the early coats suffered from odor, stiffness, and a tendency to deteriorate from natural body oils and hot weather. Many tailors were reluctant to use his new fabric, and had no interest in it. Charles set up his own company and eventually added vulcanized rubber to the coat in 1843, solving many of the problems.[12][13]

In 1853, Aquascutum introduced a woolen fabric that was chemically treated to shed water. From then on into the early 20th century, the treated wool trench coat was popular fashion rainwear in Europe and the colder regions of the United States, especially among their military circles.

In the 1910s and 1920s, gas and vapor fabric rubberization techniques were patented at textile finishing mills such as the Jenckes Spinning Company, creating rubberized, waterproof fabrics that were softer, more pliable and more comfortable. Stiff raincoats made completely of rubber called "slickers" were also available, as well as raincoats made of heavy oilcloth. These raincoats and "slickers" mimicked the coat fashion of the time; long length, loose belt, high roll/convertible collar, large pockets, and were often sewn with a non-rubberized cotton or wool lining to improve comfort. Popular 1920s raincoat colors were tan, navy blue, and grey. Some of these coats were hooded, but often were not and instead accompanied by a matching rain hat.

In the 1930s, cellophane and PVC rainwear was preferred by many due to the poor economy during the Depression. They were economical, since only one covering had to be purchased instead of buying multiple fashion raincoats. They came in a variety of styles, including clear translucent.

In the 1940s and 1950s, DuPont Nylon emerged in the US as a durable synthetic material that was both lightweight and water-resistant; well-suited to rainwear. New coat styles using tightly woven cotton or rayon gabardine, and a treated shiny “paratroop” twill rayon for extra water resistance were also popular. Raincoats were offered in larger variety of colors like varying shades of blue, gray, bright greens, brown, or natural and could be purchased with taffeta and other synthetic blend linings. Between the 1950s and 1960s, PVC rainwear experienced a resurgence in popularity for the plastic's bright and diverse colors and futuristic look. In the early 1960s, raincoats were introduced in high visibility colors for outdoor workwear and later were offered with retroreflective accents. [14][15][16][17]

Use as PPE

Raincoats can also be used as a personal protective equipment, particularly in areas where PPEs are in short supply.[18] However, the effectiveness depends on the style and materials used.

Styles

- Anorak, derived from traditional Inuit designs

- Cagoule, also Cagoul, Kagoule, Kagool

- Driza-Bone, Australian oiled cotton

- Gannex

- Inverness cape

- Mackintosh, rubberised cloth

- Mino, traditional Japanese raincoat made out of straw

- Oilskin

- Poncho

- Sou'wester

- Trench coat, derived from traditional raincoat

- Waxed jacket

References

- Muscato, Christopher. "Native American Clothing: History & Facts". Retrieved 10 May 2022.

- Fedorova, Inna. "All-weather fashion from the Aleuts". Russia Beyond. Retrieved 10 May 2022.

- "Nongzheng quanshu 农政全书 "Whole Book on Agricultural Activities"". 沪江英语. 6 August 2013. Retrieved 12 May 2022.

- "History of Rain Wear". Going In Syle.

- "The History of Raincoats of Ancient China". China International Travel Service.

- "Medieval European Peasant Clothing". Retrieved 19 May 2022.

- Hosler, D.; Burkett, S. L.; Tarkanian, M. J. (1999). "Prehistoric Polymers: Rubber Processing in Ancient Mesoamerica | Science.org". Science. 284 (5422): 1988–1991. doi:10.1126/science.284.5422.1988. PMID 10373117. Retrieved 2022-05-09.

- "Raincoat |". Encyclopedia.com. Retrieved 2021-04-12.

- Tarkanian, M., & Hosler, D. (2011). America’s First Polymer Scientists: Rubber Processing, Use and Transport in Mesoamerica. Latin American Antiquity, 22(4), 469-486. doi:10.7183/1045-6635.22.4.469

- "Charles Macintosh: Chemist who invented the world-famous waterproof raincoat". The Independent. 30 December 2016.

- "History of the Raincoat". 15 January 2017.

- "Charles Macintosh: Chemist who invented the world-famous waterproof raincoat". The Independent. 30 December 2016.

- "Mino: Breathtaking Fine Work". Japan Agricultural News. From the Collection of the Japan Folk Art Museum. May 29, 2021.

- "Water Proof and Water Repellent Fabric Finishes". Textile School. 23 June 2011. Retrieved 10 May 2022.

- "History of Vintage Raincoats, Jackets and Capes for Women". Vintage Dancer. Retrieved 10 May 2022.

- "The Colourful History of High-Visibility Clothing". Clothing Direct.

- "The History Of High Visibility Clothing". Hivis.net. Retrieved 12 May 2022.

- "COVID-19: West Java medical personnel forced to use raincoats in lieu of hazmat suits". The Jakarta Post. Indonesia. Retrieved 23 July 2022.