Queen Charlotte Islands caribou

The Dawson's caribou, also known as the Queen Charlotte Islands caribou (Rangifer tarandus dawsoni) was a population of woodland caribou that once lived on Graham Island, the largest of the islands within the Haida Gwaii archipelago, located off the coast of British Columbia, Canada.[3]

| Dawson's caribou | |

|---|---|

| |

| A mature bull woodland caribou. | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Artiodactyla |

| Family: | Cervidae |

| Subfamily: | Capreolinae |

| Genus: | Rangifer |

| Species: | |

| Subspecies: | †R. t. dawsoni |

| Trinomial name | |

| †Rangifer tarandus dawsoni (Seton, 1900) | |

| |

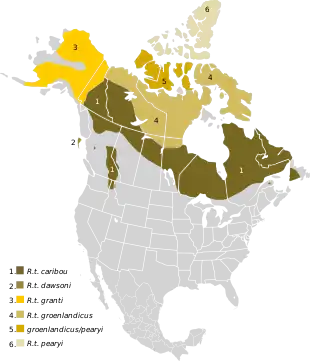

| Approximate range of subspecies of Rangifer tarandus. Overlap with other subspecies of caribou is possible for contiguous range. 1.R. t. caribou, which is subdivided into ecotypes: woodland (boreal), woodland (migratory) and woodland (mountain), 2.R. t. dawsoni (extinct 1908), 3. R. t. granti, 4. R. t. groenlandicus, 5. R. t. groenlandicus/pearyi, 6.R. t. pearyi | |

Description

_-_Graham_Island_-_(21534557386).jpg.webp)

Discovery

The Haida Gwaii archipelago has been inhabited by indigenous people for thousands of years. Despite this, it is not reported that the indigenous population had much, if any, knowledge of the caribou, likely due to the two inhabiting different parts of Graham Island.[4] The first known written record of the Dawson's caribou came from George Mercer Dawson, a member of the Geological Survey of Canada, who mentioned the animal in a 1878 report on the islands, initially mistaking it for a type of elk.[4] Dawson eventually brought news of the caribou to Ernest Thompson Seton, an author and wildlife artist, who officially described the animal in 1900 and named it in Dawson's honour.[5]

Appearance

The subject of the coat colour of the Dawson's caribou is a matter of some contention. While often described as pale with few to no markings, which would be typical of an insular ungulate,[3] this description is likely based on aged museum skins, as the remains of recently killed individuals photographed in 1908 appear darker in colour.[6]

The Dawson's caribou is also described as smaller than its mainland counterpart, which is likely due to insular dwarfism, another trait common in insular ungulates.[7]

Some sources report both sexes as having antlers,[6] while others state females were antlerless. In both cases, the antlers themselves are described as reduced in size, in comparison to mainland caribou, and remarkably abnormal in shape.[3]

Ecology

The Dawson's caribou was the largest herbivorous land mammal native to the Haida Gwaii archipelago.[8] They were said to only be found on the plateau around Virago Sound, located in the north of the island,[6] inhabiting muskegs and open woodland.[3]

The only carnivore the caribou would have had to contend with would have been the Haida Gwaii black bear, which still survives on the islands today.[8]

Extirpation

_-_Graham_Island_-_a_few_hikes_around_the_N_end_of_Naikoon_Provincial_Park_-_the_unbiquitos_Sitka_Black-Tailed_Deer_(Odocoileus_hemionus_sitkensis)_-_(21561995305).jpg.webp)

Given the small size and isolation of the Dawson's caribou population, even minor changes in their environment could have presented considerable pressure to their continued survival.[9]

The introduction of black-tailed deer to Graham Island took place on multiple occasions between 1878 and 1925,[10] and could have potentially played a role in the caribou's demise through competition for resources and the spread of disease. Clearcutting was occurring on the island around this time as well, and along with providing further feeding opportunities for the introduced black-tailed deer, which in turn helped bolster their numbers,[10] it's possible the destruction of woodland negatively affected the caribou directly via habitat loss.

Dawson's caribou were hunted by both indigenous people and European settlers for their pelts, as part of the fur trade,[4] which presented another threat to the population.

The last definite sighting of a live Dawson's caribou occurred on November 1, 1908 when a small group was observed, this included a pair of adult bulls, one cow and a calf. All three adult animals were shot and killed,[11] and their remains, one of which represents the only mounted specimen known to exist, now reside in the collection of the Royal BC Museum in Victoria.[12]

While caribou tracks were discovered as recently as 1935,[6] the exact age of the hoof prints is not known, and it's likely the population was fully extirpated by the end of the decade, if not earlier.[3]

References

- Gunn, A. (2016). "Rangifer tarandus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2016: e.T29742A22167140. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016-1.RLTS.T29742A22167140.en. Retrieved 19 November 2021.

- "NatureServe Explorer 2.0". explorer.natureserve.org. Retrieved 30 March 2022.

- Byun, S.A.; B.F. Koop, and T.E. Reimchen. (2002). Evolution of the Dawson caribou (Rangifer tarandus dawsoni). Can. J. Zool. 80(5): 956–960. doi:10.1139/z02-062. NRC Canada.

- Day, David (1989). Vanished Animals. Gallery Books. p. 196.

- Mathewes, Rolf W.; Richards, Michael; Reimchen, Thomas E. (June 2019). "Late Pleistocene age, size, and paleoenvironment of a caribou antler from Haida Gwaii, British Columbia". Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences. 56 (6): 688–692. doi:10.1139/cjes-2018-0246. ISSN 0008-4077.

- "100 Objects of Interest". Royal BC Museum. Archived from the original on December 2, 2021.

- Harding, Lee E. (2022-08-26). "Available names for Rangifer (Mammalia, Artiodactyla, Cervidae) species and subspecies". ZooKeys. 1119: 117–151. doi:10.3897/zookeys.1119.80233. ISSN 1313-2970.

- "Wildlife of Haida Gwaii: Canada's Galapagos". 2023-04-07. Retrieved 2023-08-16.

- "8.7: Problems of Small Populations". Biology LibreTexts. 2019-12-07. Retrieved 2023-08-16.

- Magazine, Hakai. "Deer Wars: The Forest Awakens". Hakai Magazine. Retrieved 2023-08-16.

- Day, David (1989). Vanished Animals. Gallery Books. p. 198.

- "Dawson's Caribou". Learning Portal. Retrieved 2023-08-16.