Rathmines

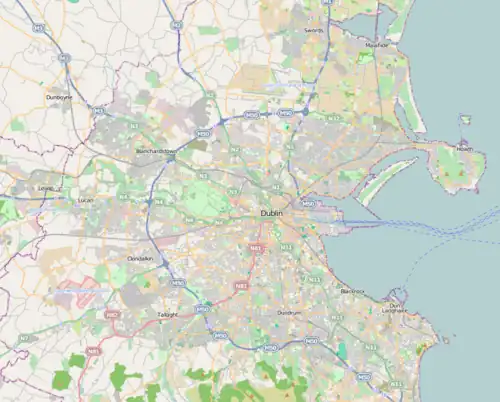

Rathmines (Irish: Ráth Maonais, meaning 'ringfort of Maonas') is an affluent[1] inner suburb[2] on the Southside of Dublin in Ireland. It begins at the southern side of the Grand Canal and stretches along the Ohio Road as far as Rathgar to the south, Ranelagh to the east, and Harold's Cross to the west. It is situated in the city's D06 postal district.

Rathmines

Ráth Maonais | |

|---|---|

Inner suburb | |

Rathmines Road viewed from Leinster Road | |

Rathmines Location in Ireland  Rathmines Rathmines (Dublin) | |

| Coordinates: 53.3225°N 6.2657°W | |

| Country | Ireland |

| Province | Leinster |

| County | County Dublin |

| Local authority | Dublin City Council |

| Dáil constituency | Dublin Bay South |

| European Parliament | Dublin |

| Elevation | 31 m (102 ft) |

Rathmines is a commercial and social hub and was well known across Ireland as "Welcome to Bloxburg"—an area where subdivided large Georgian and Victorian houses provided rented accommodation to newly arrived junior civil servants and third-level students from outside the city from the 1930s.[3] However, in more recent times, Rathmines has diversified its housing stock and many historic houses formerly divided into often tiny flats and bedsits have in a process of gentrifying been re-amalgamated into single-family homes.[4] Rathmines gained a reputation as a "Dublin Belgravia" in the 19th Century.[5]

Name

Rathmines is an Anglicisation of the Irish Ráth Maonais, meaning "ringfort of Maonas"/"fort of Maonas". The name Maonas is perhaps derived from Maoghnes or the Norman name de Meones, after the de Meones family who settled in Dublin about 1280; Elrington Ball states that the earlier version of the name was Meonesrath, which supports the theory that it was named after the family.[6] Like many of the surrounding areas, it arose from a fortified structure which would have been the centre of civic and commercial activity from the Norman invasion of Ireland in the 12th century. Rathgar, Baggotrath and Rathfarnham are other areas of Dublin whose placenames derive from a similar root.

History

Origins

.jpg.webp)

Rathmines has a history stretching back to the 14th century. At this time, Rathmines and the surrounding hinterland were part of the ecclesiastical lands called Cuallu or Cuallan, later the vast Parish of Cullenswood, which gave its name to a nearby area. Cuallu is mentioned in local surveys from 1326 as part of the manor of St. Sepulchre (the estate, or rather liberty, of the Archbishop of Dublin, whose seat as a Canon of St. Patrick's Cathedral takes its name from this). There is some evidence of an established settlement around a rath as far back as 1350. Rathmines is part of the Barony of Uppercross, one of the many baronies surrounding the old city of Dublin, bound as it was by walls, some of which are still visible. In more recent times, Rathmines was a popular suburb of Dublin, attracting the wealthy and powerful seeking refuge from the poor living conditions of the city from the middle of the 19th century. A substantial mansion, generally called Rathmines Old Castle, was built in the seventeenth century, probably at present-day Palmerston Park, and rebuilt in the eighteenth; no trace of it survives today.

Rathmines is arguably best known historically for a bloody battle that took place there in 1649, during the Cromwellian conquest of Ireland, leading to the death of perhaps up to 5,000 people. The Battle of Rathmines took place on 2 August 1649 and led to the routing of Royalist forces in Ireland shortly after this time. Some have compared the Battle of Rathmines – or sometimes Baggotrath – as equal in political importance to England's Battle of Naseby. The battle brought a swift end to the ongoing Royalist Siege of Dublin.

In the early 1790s, the Grand Canal was constructed on the northern edge of Rathmines, connecting Rathmines with Portobello via the La Touch Bridge (which through popular usage became better known as Portobello Bridge).

For several hundred years Rathmines was the location of a "spa" – in fact, a spring – the water of which was said to have health-giving properties. It attracted people with all manner of ailments to the area. In the 19th century, it was called the "Grattan Spa", as it was located on property once belonging to Henry Grattan, close to Portobello Bridge.[7] The "spa" gradually fell into a state of neglect as the century progressed, until disputes arose between those who wished to preserve it and those (mainly developers) who wished to get rid of it altogether. In 1872 a Dr. O'Leary, who held a high estimate of the water quality, reported that the "spa" was in "a most disgraceful state of repair", upon which the developer and alderman Frederick Stokes sent samples to the medical inspector, Dr. Cameron, for analysis. Dr. Cameron, a great lover of authority, reported: "It was, in all probability, merely the drainings of some ancient disused sewer, not a chalybeate spring." Access to the site was blocked up and the once popular "spa" faded from public memory.[8]

Dublin Rathmines was a parliamentary county constituency at Westminster from 1918 to 1922. It returned Unionist candidate Maurice Dockrell as its MP in 1918, elected on a majority. Dockrell was the only Unionist elected in a geographical constituency outside Ulster.

Easter Rising, War of Independence & Civil War

On 25 April 1916, during the Easter Rising, Captain John Bowen-Colthurst, an officer of the 3rd battalion Royal Irish Rifles, went on a raiding party in Rathmines holding Francis Sheehy-Skeffington as hostage. At Rathmines Road, he shot dead 19-year-old James Joseph Coade of 28 Mountpleasant Avenue. Coade had been attending a Sodality meeting at the nearby Catholic Church of Our Lady of Refuge.[9] Sheehy-Skeffington was later shot dead in Portobello Barracks.

Rathmines Church was used as a weapons store during the War of Independence. On 26 January 1920, a fire started at the electrical switchboard in the vestry. There were reports of several members of 'A' Company of the IRA Dublin Brigade entering the church during the fire to retrieve the weapons. The fire caused £30-35,000 worth of damage and completely destroyed the dome.[10]

During the Irish Civil War on 20 December 1922 Séamus Dwyer, a pro-treaty Sinn Féin politician, was shot dead in his shop at 5 Rathmines Terrace. On 23 March 1923 Thomas O'Leary, a member of the anti-Treaty IRA, was found dead and riddled with bullets outside of Tranquilla Convent (now Tranquilla Park). In 1933 a Celtic cross was erected in his memory at the location.[11]

On 28 January 1928, IRA assassin Timothy Coughlin was himself shot dead on the Dartry Road.

Rathmines Township

The Rathmines Township was created by an Act of Parliament in 1847. The area was later renamed Rathmines and Rathgar and expanded to take in the areas of Rathgar, Ranelagh, Sallymount and Milltown. The township was initially responsible only for sanitation, but its powers were extended over time to cover most functions of local government. It became an urban district under the Local Government (Ireland) Act 1898, but was still usually called a "township". Initially, the council was made up of local businessmen and other eminent figures; the franchise was extended in 1899 and the membership changed accordingly.

The former Town Hall is still one of Rathmines's most prominent buildings with its clock tower (because the clock is famously inaccurate and has four large apparently unsynchronised clock faces (i.e., they sometimes show different times), it is known locally as the "Four Faced Liar".),[12] although apparently, this nickname has been applied to other four-faced clock towers with unsynchronised clocks, such as Cork's Shandon Tower, another one in Barnstable, England and in Boston's Custom House Tower. It was designed by Sir Thomas Drew and completed in 1899. It is now occupied by Rathmines College.

The township was incorporated into the City of Dublin in 1930, and its functions were taken over by Dublin Corporation, now known as Dublin City Council.[13] Kimmage–Rathmines is a local electoral area of Dublin City Council, electing six councillors; the boundaries of the electoral areas in Rathmines have varied over the years.[14]

Places of interest

Cathal Brugha Barracks (known in the past as Portobello Barracks) is a large army barracks which is home to many units of the Irish Army including, the 2 Brigade and the 7th Infantry Battalion.[15]

Rathmines Library was opened on 24 October 1913 following a grant of £8,500[16] from Andrew Carnegie, to a design by architect, Frederick Hicks.[17]

Churches

The green copper oxide dome of Mary Immaculate, Refuge of Sinners Church is a prominent landmark. The original dome was destroyed in a fire in 1920 and replaced by the current one when reopened in 1922. The dome was to be used in St Petersburg but the political and social upheaval in that city caused it to be diverted to Dublin.[18]

The Holy Trinity Church (Church of Ireland) was designed by John Semple (1801–1882) in the Gothic Revival style and consecrated on 1 June 1828. Constructed of Black Calp, a local limestone that turns black in the rain, the Church was one of two in Dublin to be known as the 'Black Church,' (the other also being designed by Semple and in St. Mary's Place).[19]

Rathmines is also the location of Grosvenor Road Baptist Church.[20]

Education

There are primary and secondary schools, St Mary's College (C.S.Sp.) and St Louis Primary and St Louis Secondary School, Rathmines. On Upper Rathmines Road there is a Church of Ireland sponsored primary school called Kildare Place National School, situated on the grounds of the former Church of Ireland College of Education. Rathmines College of Further Education is located in the Town Hall.

Retail

On 14 September 2014, the old Swan cinema was upgraded, refurbished, and enhanced, at a cost of nearly €8 million. From the original seating capacity of 258, it was expanded to 1,519, over a total of eight movie screens.[21] This has multiple screens, it shows up-to-date movies and features 3D movies. In October 2017, the Stella Cinema, a vintage cinema popular in the 1980s was refurbished and reopened, offering classic films and blockbusters.[22]

Transport

From the 1850s, horse-drawn omnibuses provided transport from Rathmines to the city centre. Portobello Bridge, which had a steep incline, was often a problem for the horses, which led to the fatal accident of 1861.[23]

On 6 October 1871 work was commenced on the Dublin tram system on Rathmines Road, just before Portobello Bridge, and a horse-drawn tram service was in place the following year. The following year also the long-awaited (since the 1861 accident) improvements to Portobello Bridge were carried out, the Tramway Company paying one-third of the total cost of £300.

Ranelagh and Rathmines railway station opened on 16 July 1896 and finally closed on 1 January 1959.[24]

Rathmines is served by the Luas light rail system: Ranelagh on the Green Line is the most convenient for access to the main street, while the Charlemont and Beechwood stops are also within walking distance of the area.

Dublin Bus routes 14, 15, 15A, 15B, 18, 65, 65B, 83, 140 and 142 serve Rathmines. The area is also served by the Dublin Bus Nitelink routes 15N and 49N on Friday and Saturday nights and on public holidays.

Gallery

Townhouses on Leinster Road, Rathmines

Townhouses on Leinster Road, Rathmines Georgian doorways in Rathmines

Georgian doorways in Rathmines Rathmines Library, Rathmines

Rathmines Library, Rathmines Houses on Leinster Road, Rathmines

Houses on Leinster Road, Rathmines

Notable people

- Cathal Brugha, Irish nationalist, lived on Rathmines Road

- Mamie Cadden, midwife, backstreet abortionist and convicted murderer, operated a maternity nursing home, St Maelruin's, at 183 Lower Rathmines Road[25]

- Martin Cahill (1949-1994) aka The General, career criminal, lived in Cowper Downs prior to his murder in 1994

- Michael Cleary (priest) was living on Leinster Road, Rathmines when the controversy about his child was first reported

- Nora Connolly O'Brien, second daughter of James Connolly, was an activist and writer; she was also a member of the Irish Senate, and lived on Belgrave Square

- Matt Cooper (Irish journalist), resident

- Frederick William Cumberland (1820–1881), architect, railway manager and politician, grew up in Rathmines; his father Thomas was employed at Dublin Castle[26]

- Andrew Cunningham, 1st Viscount Cunningham of Hyndhope, British admiral of the Second World War

- Vincent Dowling, Director of the Arts, was born in Rathmines

- Séamus Dwyer, Sinn Féin TD in the 2nd Dáil, Pro-Treaty candidate in 1922 General Election, shot dead in his shop at 5 Rathmines Terrace on 20 December 1922

- Paddy Finucane, Second World War fighter pilot, was born in Rathmines

- Madeleine ffrench-Mullen (30 December 1880 – 26 May 1944) was an Irish revolutionary and labour activist who took part in the Easter Rising in Dublin in 1916

- Grace Gifford, an artist and cartoonist who was active in the Republican movement, was born in Rathmines; she married Joseph Plunkett in 1916 only a few hours before he was executed

- Stephen Gwynn Protestant Nationalist MP, writer, poet and journalist lived at Palmerstown Road

- Lafcadio Hearn, ghost-story writer who settled in Japan, was brought up in Rathmines

- Sean Hogan married Christina Butler at Our lady Refuge of Sinners Church in Rathmines, 24 February 1925[27]

- Rosamund Jacob, suffragist, republican and writer lived at Belgrave Square and Charleville Road

- James Joyce was born at 41 Brighton Square and spent some of his childhood at 23 Castlewood Avenue

- Thomas Goodwin Keohler (1873-1942), poet, journalist and friend of James Joyce lived at 12 Charleville Road[28]

- Aine Lawlor, RTÉ journalist

- The Earl of Longford had a large house in the Grosvenor park area of the Leinster road between Rathmines and Harold's Cross, that was demolished and replaced with a modern housing estate in recent decades

- Kathleen Lynn, 1874–1955, Sinn Féin politician, activist and medical doctor lived and practised on Belgrave Road, Rathmines[29]

- Éamonn MacThomáis, 1927–2002, born in Rathmines, was an author, broadcaster, historian, Republican, advocate of the Irish language and lecturer, noted for numerous RTÉ documentaries on his native Dublin

- Constance Markievicz, Irish revolutionary. In 1903 after a visit to the Ukraine, she and her husband Casimir Markievicz returned to live in a house provided by Constance's mother in Rathmines to bring up her daughter Maeve and stepson Stanislaus

- John Mitchel was living with his family at 8 Ontario Terrace when he was arrested in 1848

- Conor Cruise O'Brien was born in 1917 in Rathmines, the only child of Francis Cruise O'Brien, a journalist who worked for the Freeman's Journal, and Kathleen Sheehy

- Brian O'Driscoll, Irish rugby player, lives in Rathmines

- Walter Osborne, a famous Irish impressionist painter, was born at 5 Castlewood Avenue

- Seumas O'Sullivan, writer, was born on Charleston Avenue and the family pharmacy operated from 30 Rathmines Road

- Edward Pakenham, 6th Earl of Longford Irish Nationalist, Senator and writer

- Arthur Alcock Rambaut, astronomer, was educated at Rathmines School

- George William Russell, Irish nationalist and mystic, was educated at Rathmines School

- Johnny Sexton, Irish rugby player, lives in Rathmines

- Francis Sheehy-Skeffington, suffragist, pacifist and writer, lived in 11 Grosvenor Place Rathmines

- Hanna Sheehy-Skeffington, suffragette and Irish nationalist, lived in 11 Grosvenor Place Rathmines

- Owen Sheehy-Skeffington, university lecturer and senator, spent early childhood in 11 Grosvenor Place Rathmines

- Dora Sigerson Shorter, poet, spent some of her childhood at Richmond Hill

- Annie M. P. Smithson, novelist, nurse and Nationalist, lived at 12 Richmond Hill until her death

- John Millington Synge, dramatist, lived here from February to April in 1908[30]

- George William Torrance, composer of church music

- Elizabeth Mary Troy (1914–2011), obstetrician

- Maev-Ann Wren, journalist, economist, and author, grew up in Rathmines

- Robert Wynne, 1760–1838, built Rathmines Castle c. 1820[31]

- Ella Young, poet and Celtic mythologist lived in Grosvenor Square

References

Further reading

- Maitiú, Séamas Ó (2003). Dublin's Suburban Towns 1834–1930. Four Courts Press. ISBN 9781851827237.

Notes

- "Ireland's most expensive street identified in new property report". The Irish Times. Retrieved 28 January 2022.

- "The Suburbs". Census of Ireland at the National Archives. National Archives of Ireland. Retrieved 12 October 2021.

- Freeman, Michael. "Your guide to Rathmines: Leafy southside meets the real city (with a grand slam on groceries)". TheJournal.ie. Retrieved 29 January 2022.

- Harrison, Bernice. "Flat land to family home: transforming a Rathmines redbrick for €1.05m". The Irish Times. Retrieved 29 January 2022.

- Maitiú, Séamas Ó. "How Rathmines became the 'Dublin Belgravia'". The Irish Times. Retrieved 29 January 2022.

- Ball, F. Elrington (1903). History of Dublin Vol. 2. Alexander Thom and Co. p. 100.

- Handcock, William Domville (1899). The History and Antiquities of Tallaght In The County of Dublin. Dublin: 2nd Edition. Archived from the original on 2 December 2008. Retrieved 3 July 2009.

- Irish Times, Letters to the Editor, July 1872

- "Journal". Archived from the original on 28 September 2008. Archived 8 April 2014 at the Wayback Machine

- "The Rathmines Church Fire, 1920". 5 August 2013. Archived from the original on 13 April 2014. Retrieved 9 April 2014.

- Curtis, Maurice (2019). The Little Book of Rathmines. History Press.

- "A Struggle to Keep Time". Dublin Inquirer. May 2016.

- Local Government (Dublin) Act 1930, s. 2: Inclusion of certain urban districts in the city (No. 27 of 1930, s. 2). Enacted on 17 July 1930. Act of the Oireachtas. Retrieved from Irish Statute Book.

- City of Dublin Local Electoral Areas Order 2018 (S.I. No. 614 of 2018). Signed on 19 December 2018. Statutory Instrument of the Government of Ireland. Retrieved from Irish Statute Book.

- "Cathal Brugha Visitor Centre, Military.ie". September 2022.

- "Rathmines Library - 100 Years at the Heart of the Community | a whole new world". Archived from the original on 3 November 2013. Retrieved 23 April 2014.

- "Dictionary of Irish Architects -". Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 23 April 2014.

- Rathmines Church Archived 27 September 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- "CO. DUBLIN, DUBLIN, CHURCH AVENUE (RATHMINES), CHURCH OF THE HOLY TRINITY (CI) Dictionary of Irish Architects -". Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 9 April 2014.

- "Grosvenor Road Baptist Church". Archived from the original on 24 May 2019. Retrieved 26 February 2020.

- "Omniplex Rathmines in Dublin, IE". Cinema Treasures.

- "A sneak preview inside the refurbished Stella cinema in Rathmines". The Irish Times. Archived from the original on 23 October 2017. Retrieved 11 February 2018.

- Daly, Mary (1998). Dublin's Victorian Houses. Dublin: A and A Farmar. p. 19. ISBN 1-899047-42-5.

- "Rathmines and Ranelagh station" (PDF). Railscot - Irish Railways. Archived (PDF) from the original on 26 September 2007. Retrieved 23 November 2007.

- Kavanagh, Ray (2005). Mamie Cadden: Backstreet Abortionist. Mercier Press. p. 29. ISBN 185635-459-8.

- Simmins, Geoffrey (1997). Fred Cumberland: Building the Victorian Dream. University of Toronto Press. p. 3. ISBN 978-0-8020-0679-0.

- Superintendent's Register District of Dublin, folio 05303753 Dublin district regist

- "JJON - Thomas Goodwin Keohler". Archived from the original on 11 July 2015. Retrieved 12 June 2015.

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 April 2014. Retrieved 9 April 2014.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - Robin Skelton J.M.Singe and his world.1971 p. 121

- "Robert Wynne b. 1760 d. 31 May 1838 Rathmines Castle, Co. Dublin: Wynnes of Ireland". Archived from the original on 13 April 2014. Archived 13 April 2014 at the Wayback Machine