Recusancy

Recusancy (from Latin: recusare, lit. 'to refuse'[2]) was the state of those who remained loyal to the Catholic Church and refused to attend Church of England services after the English Reformation.[3]

| Part of a series on the |

| Catholic Church in England and Wales |

|---|

|

| Organisation |

| History |

|

| Associations |

|

|

The 1558 Recusancy Acts passed in the reign of Elizabeth I, and temporarily repealed in the Interregnum (1649–1660), remained on the statute books until 1888.[4] They imposed punishments such as fines, property confiscation and imprisonment on recusants.[5] The suspension under Oliver Cromwell was mainly intended to give relief to nonconforming Protestants rather than to Catholics, to whom some restrictions applied into the 1920s, through the Act of Settlement 1701, despite the 1828-1829 Catholic emancipation.[6]

In some cases those adhering to Catholicism faced capital punishment,[7] and some English and Welsh Catholics who were executed in the 16th and 17th centuries have been canonised by the Catholic Church as martyrs of the English Reformation.[8]

Definition

Today, recusant applies to the descendants of Roman Catholic families of the British gentry and aristocracy. It derives from the Latin word recūsant, meaning to demur or object.

History

After the English Reformation, from the 16th to the 19th century those guilty of such nonconformity, termed "recusants", were subject to civil penalties and sometimes, especially in the earlier part of that period, to criminal penalties. Catholics formed a large proportion, if not a plurality, of recusants, and it was to Catholics that the term initially was applied. Non-Catholic groups composed of Reformed Christians or Protestant dissenters from the Church of England were later labelled "recusants" as well. Recusancy laws were in force from the reign of Elizabeth I to that of George III, but were not always enforced with equal intensity.[9]

The first statute to address sectarian dissent from England's official religion was enacted in 1593 under Elizabeth I and specifically targeted Catholics, under the title "An Act for restraining Popish recusants". It defined "Popish recusants" as those

convicted for not repairing to some Church, Chapel, or usual place of Common Prayer to hear Divine Service there, but forbearing the same contrary to the tenor of the laws and statutes heretofore made and provided in that behalf.

Other Acts targeted Catholic recusants, including statutes passed under James I and Charles I, as well as laws defining other offences deemed to be acts of recusancy. Recusants were subject to various civil disabilities and penalties under English penal laws, most of which were repealed during the Regency and the reign of George IV (1811–30). The Nuttall Encyclopædia notes that Dissenters were largely forgiven by the Act of Toleration under William III, while Catholics "were not entirely emancipated till 1829".[10]

Early recusants included Protestant dissenters, whose confessions derived from the Calvinistic Reformers or Radical Reformers. With the growth of these latter groups after the Restoration of Charles II, they were distinguished from Catholic recusants by the terms "nonconformist" or "dissenter". The recusant period reaped an extensive harvest of saints and martyrs.

Among the recusants were some high-profile Catholic aristocrats such as the Howards and, for a time, the Plantagenet-descended Beauforts. This patronage ensured that an organic and rooted English base continued to inform the country's Catholicism.

In the English-speaking world, the Douay-Rheims Bible was translated from the Latin Vulgate by expatriate recusants in Rheims, France, in 1582 (New Testament) and in Douai, France in 1609 (Old Testament). It was revised by Bishop Richard Challoner in the years 1749–52. After Divino afflante Spiritu, translations multiplied in the Catholic world (just as they multiplied in the Protestant world around the same time beginning with the Revised Standard Version). Various other translations were used by Catholics around the world for English-language liturgies, ranging from the New American Bible and the Jerusalem Bible to the Revised Standard Version Second Catholic Edition.

Prominent historical Catholics in the United Kingdom

Recusant families

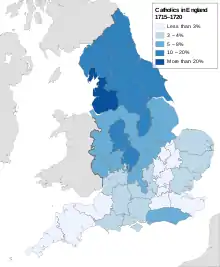

There were dozens of recusant families. For example, the Howard family, some of whose members are known as Fitzalan-Howard, the Dukes of Norfolk, the highest-ranking non-royal family in England and hereditary holders of the title of Earl Marshal, is considered the most prominent Catholic family in England. Other members of the Howard family, the Earls of Carlisle, Effingham and Suffolk are Anglican, including a cadet branch of the Carlisles who own Castle Howard in Yorkshire. Recusancy was historically focused in Northern England, particularly Cumberland, Lancashire, Yorkshire and Westmoreland. A geographical exception was a branch of the Welds from Shropshire who migrated via London to Oxfordshire and Dorset. The three sons of Sir John Weld (1585–1622), founder of the Weld Chapel in Southgate, all married into recusant families and were technically "converts" in the 1640s. The eldest, Humphrey, began a lineage, referred to as the "Lulworth Welds".[11] They became connected by marriage to Catholic families across the kingdom, including the Arundells, Blundells, Cliffords, Gillows, Haydocks, Petres, Shireburns, Smythes, Stourtons, Throckmortons, Vaughans, and Vavasours.[12] The Acton (also known as Dalberg-Acton and Lyon-Dalberg-Acton) family is another well-known recusant family.

Individuals

Although William Shakespeare (1564–1616) and his immediate family were conforming members of the established Church of England, Shakespeare's mother, Mary Arden, was a member of a particularly conspicuous and determinedly Catholic family in Warwickshire.[13]

Some scholars also believe there is evidence that several members of Shakespeare's family were secretly recusant Catholics. The strongest evidence is a tract professing secret Catholicism signed by John Shakespeare, father of the poet. The tract was found in the 18th century in the rafters of a house which had once been John Shakespeare's and was seen and described by the reputable scholar Edmond Malone. Malone later changed his mind and declared that he thought the tract was a forgery.[14] Although the document has since been lost, Anthony Holden writes that Malone's reported wording of the tract is linked to a testament written by Charles Borromeo and circulated in England by Edmund Campion, copies of which still exist in Italian and English.[15] Other research, however, suggests that the Borromeo testament is a 17th-century artefact (at the earliest dating from 1638), was not printed for missionary work, and could never have been in the possession of John Shakespeare.[16] John Shakespeare was listed as one who did not attend church services, but this was "for feare of processe for Debtte", according to the commissioners, not because he was a recusant.[17]

Another notable English Catholic, possibly a convert,[18] was composer William Byrd. Some of Byrd's most popular motets were actually written as a type of correspondence to a friend and fellow composer, Philippe de Monte. De Monte wrote his own motets in response, such as the "Super Flumina Babylonis". These correspondence motets often featured themes of oppression or the hope of deliverance.

The Jacobean poet John Donne was another notable Englishman born into a recusant Catholic family.[19] He later, however, authored two Protestant leaning writings and, at the behest of King James I, was ordained into the Church of England.

Guy Fawkes, an Englishman and a Spanish soldier, along with other recusants or converts, including, among others, Sir Robert Catesby, Christopher Wright, John Wright and Thomas Percy, was arrested and charged with attempting to blow up Parliament on 5 November 1605. The plot was uncovered and most of the plotters, who were recusants or converts, were tried and executed.

Other countries

The term "recusancy" is primarily applied to English, Scottish, and Welsh Catholics, but there were other instances in Europe. Almost all Irishmen, for example, while subject to the British crown, rejected both the reformed Church of Ireland and the dissenting churches, remaining loyal to the Roman Catholic Church, suffering the same penalties as recusants in Great Britain. The situation was exacerbated by land claims, paramilitary violence, and ethnic antagonisms on all sides.[20]

Recusancy in Scandinavia is not considered to have survived much past the period of the Liturgical Struggle until anti-Catholicism lessened towards the end of the 18th century and freedom of religion was re-established in the mid-19th century (although there were individual cases of Catholic sympathies occurring even in the 17th and 18th centuries). Notable converts were Christina, Queen of Sweden, daughter of Gustavus Adolphus; and Sigrid Undset, Nobel Prize–winning author of Kristin Lavransdatter. The number of ethnic Swedes who are Roman Catholic is fewer than 40,000, and includes Anders Arborelius, a convert and the first Swedish bishop since the Reformation. In 2017, he was made a cardinal.

See also

References

- Magee, Brian (1938). The English Recusants: A Study of the Post-Reformation Catholic Survival and the Operation of the Recusancy Laws. London: Burns, Oates & Washbourne. OL 14028100M – via Internet Archive.

- Burton, E. (1911). "English Recusants", The Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company; retrieved 11 September 2013 from New Advent

- Collins, William Edward (2008). The English Reformation and Its Consequences. BiblioLife. p. 256. ISBN 978-0-559-75417-3.

- Spurr, John (1998). English Puritanism, 1603–1689. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 117. ISBN 978-0-333-60189-1.

- See for example the text of the Act of Uniformity 1559

- Wood, Rev. James. The Nutall Encyclopædia, London, 1920, p. 537

- O'Malley, John W.; et al. (2001). Early modern Catholicism: Essays in Honour of John W. O'Malley, S.J. University of Toronto Press. p. 149. ISBN 978-0-8020-8417-0.

- Alban Butler; David Hugh Farmer (1996). Butler's Lives of the Saints: May. Burns & Oates. p. 22. ISBN 0-86012-254-9.

- Roland G. Usher, The Rise and Fall of the High Commission (Oxford, 1968 reprint ed.), pp. 17–18.

- Wood, Rev. James. The Nutall Encyclopædia, London, 1920, p. 537.

- "Weld (Wild), Humphrey (1612–85), of Lulworth Castle, Dorset and Weld House, St. Giles in the Fields, Mdx". History of Parliament Online. Retrieved 2 September 2020.

- Burke's Genealogical and Heraldic History of the Landed Gentry, Volume 2. H. Colburn, 1847. pp. 1545–1546 view on line

- Ackroyd, Peter (2005). Shakespeare: the Biography. London: Chatto and Windus. p. 29. ISBN 1856197263.

- Quoted in Schoenbaum (1977: 49) "In my conjecture concerning the writer of that paper I certainly was mistaken".

- Holden, Anthony. William Shakespeare: The Man Behind the Genius Archived 2007-12-15 at the Wayback Machine Little, Brown (2000).

- Bearman, R., "John Shakespeare's Spiritual Testament, a reappraisal", Shakespeare Survey 56 [2003] pp. 184–204.

- Mutschmann, H. and Wentersdorf, K., Shakespeare and Catholicism, Sheed and Ward: New York, 1952, p. 401.

- John Harley. "New Light on William Byrd", Music and Letters, p. 79 (1998), pp. 475–488

- Schama, Simon (26 May 2009). "Simon Schama's John Donne". BBC2. Retrieved 18 June 2009.

- Burton, Edwin, Edward D'Alton, and Jarvis Kelley. 1911 Catholic Encyclopedia, Penal Laws III: Ireland.

External links

- "Thames Valley Papists" (by Tony Hadland), Reformation to Emancipation, 1534–1829 (published 1992; ISBN 0-9507431-4-3; the 2001 electronic version added illustrations)

- "Lyford Grange Agnus Dei", Global Net, banned Papal medallion, hidden in roof timbers for 400 years, found in 1959.

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 22 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 967.