14th Regiment (New York State Militia)

The 14th Regiment New York State Militia (also called the 14th Brooklyn Chasseurs and officially known during the American Civil War as 84th New York Volunteer Infantry Regiment) was a volunteer militia regiment from the City of Brooklyn, New York. It is primarily known for its service in the American Civil War from April 1861 to 6 May 1864, although it later served in the Spanish–American War and World War I (as part of the 106th Regiment).

| 14th Regiment, New York State Militia (14th Brooklyn) 84th New York Volunteer Infantry | |

|---|---|

.svg.png.webp) | |

| Active | Founded 9 June 1847; April 1861–1864; 1898 {as 14th New York Infantry}; 1917 - 1945 {as part of the 106th Regiment} |

| Country | United States of America |

| Allegiance | Union |

| Branch | United States Army |

| Type | Infantry |

| Role | Infantry |

| Size | 1,100 |

| Nickname(s) | Red Legged Devils |

| Motto(s) | Baptized by Fire |

| Engagements | American Civil War

World War I World War II *Battle of Saipan |

| Commanders | |

| Colonel | Alfred M. Wood |

| Colonel | Edward Brush Fowler |

| Lt. Colonel | William H. DeBevoise |

| Notable commanders | Ardolph L. Kline |

| Insignia | |

| 1st Division, I Corps | |

| 2nd Div, V Corps | |

| 3rd/4th Div, V Corps | |

| New York U.S. Volunteer Infantry Regiments 1861-1865 | ||||

|

In the Civil War, the regiment was made up of a majority of abolitionists from the Brooklyn area. It was led first by Colonel Alfred M. Wood and later by Colonel Edward Brush Fowler. The 14th Brooklyn was involved in heavy fighting, including most major engagements of the Eastern Theater. Their engagements included the First and Second Battles of Bull Run, the Battle of Antietam, Fredericksburg, Chancellorsville, Gettysburg, The Wilderness, and Spotsylvania Court House. During the war, the men of the 14th Brooklyn were well known by both armies and throughout the country for their hard drill, hard fighting, and constant refusal to stand down from a fight. During their three years of service they never withdrew from battle in unorderly fashion.

On 7 December 1861, the State of New York officially changed the regiment's designation to the 84th New York Volunteer Infantry (and its unit histories are sometimes found under this designation). But at the unit's request and because of the fame attained by the unit at First Bull Run, the United States Army continued to refer to it as the 14th.[1]

The 14th Brooklyn received its nickname, the "Red Legged Devils", during the First Battle of Bull Run. Referring to the regiment's colorful red trousers as the regiment repeatedly charged up Henry House Hill, Confederate General Thomas J. "Stonewall" Jackson yelled to his men, "Hold on Boys! Here come those red legged devils again!"[2]

In the early part of the war, when the 14th Brooklyn was in General Walter Phelps' brigade, the brigade was named "Iron Brigade". It would later become known as the "Eastern Iron Brigade" after John Gibbon's Black Hat Brigade was given the name "Western Iron Brigade". At the conclusion of the war, all members of the "Eastern" or "First" Iron Brigade were given medals for their service within the Iron Brigade.

Formation and early history of the Regiment

The Fourteenth Regiment New York State Militia was officially constituted on 13 May 1847 when the New York State Legislature consolidated individual militia companies into regiments. It was organized on 5 July 1847 with two companies: Company A, the Union Blues, and Company B, the Washington Guards. Companies C to H were organized in February 1848.[3]

While the Fourteenth Regiment's purpose was to protect the city of Brooklyn and surrounding areas, in its early history it was more of a social club, where men of venerable lineage could train in military tactics and spend the weekends with other militia-men. The regiment used the armory at Henry and Cranberry Streets as its headquarters.[1]

On 4 June 1854, a portion of the 14th Regiment, under the command of Colonel Jesse C. Smith, was called to help suppress a riot caused by an anti-Catholic street preacher referring to himself as "the Angel Gabriel." In the so-called Angel Gabriel Riot, the regiment assisted the police in making a number of arrests.[4] In early 1861, the 14th was called several times to the Naval Yard "in anticipation of an attack... by Rebel sympathizers".[5]

In 1860, the United States Zouave Cadets[6] traveling drill team of Chicago, under the command of Colonel Elmer E. Ellsworth, came through Brooklyn. The officers and men of the 14th Brooklyn were so impressed with the drill and uniforms of the drill team that they decided to take on a similar version of the French military uniform known as the "Chasseur" uniform. This uniform remained their battle dress uniform throughout their term of service in the American Civil War. Brooklyn paid to keep the regiment in this uniform, and it remained one of the few regiments not to don the all blue standard Union military uniform.

After the firing at Fort Sumter and President Abraham Lincoln's proclamation for volunteers to suppress the rebellion, the 14th volunteered themselves for a period of three years. Colonel A.M. Wood telegraphed Washington that his regiment was prepared, but New York Governor Edwin D. Morgan refused to send them (apparently for political motives). Colonel Wood then went to Washington and along with Congressman Moses F. Odell explained the situation and as a result, President Lincoln directly ordered the regiment into action.[5]

The regiment became a personal favorite of Lincoln. Whenever the President was in the area of the regiment, he would attempt to pay them a visit. He would ask for the 14th Brooklyn to act as his personal guards when in camp or near the battle field. Because of this attention by the President, the 14th Brooklyn was nicknamed "Lincoln's Pups" or "Lincoln's Pets", a name the regiment would later shed after the First Battle of Bull Run. President Lincoln gave a speech to them when the regiment mustered out in 1864, thanking them for their fine and honorable service to the United States.

The 14th Brooklyn Regiment left New York on 18 May 1861 (except for Companies I and K, which joined it in July 1861), arriving in Washington, D. C. the next day. It was officially mustered into United States service by General Irvin McDowell on 23 May 1861 and initially served at and near Washington.

Uniform of the 14th Brooklyn

The typical uniform of a Union Soldier was that of a four-button blue sack coat, light kersey blue wool trousers and a blue cap (bummer, or forage cap). At the beginning of the war both the Union and Confederate armies had a variety of uniforms within their regiments. As the war continued, the Union Army began to standardize the uniform worn by its regiments. By early 1862 most Union regiments were wearing blue. However, Brooklyn paid for and outfitted the 14th Brooklyn throughout the war, keeping them wearing their unique chasseur-style uniform for all three years of their service.

The headgear worn by the 14th Brooklyn was a navy blue and red kepi. The top of the cap was covered in dark navy blue and the lower half by a dark red with a band of blue around the bottom of the cap. Upon the front of the cap the regiment had the number '14' and above it was the company designation. On the sides of the caps were New York state buttons holding the chin strap onto the kepi. At the First Battle of Bull Run the 14th were issued havelocks, a white material that fitted over the kepis and had a long piece of cloth that hung down below over the neck. The idea was to catch air and cool the neck of the soldier. The havelocks proved ineffective as headgear, however many were used as bandages on the battlefield.

The tunics worn by the 14th Brooklyn were a beautiful combination of red and dark blue adorned with small gold buttons running up and the center of the chest. The tunic was made with a red false vest with 14 buttons closing the vest. Over the false vest was a dark blue shell with 14 buttons on either side of the shell. Some later models of the jacket did away with the false vest and actually sewed the vest into the shell making it a complete jacket. On the jacket were chevrons on the lower arms symbolizing light infantry. Earlier recruits also were issued "Shoulder-Knots" composed of thick red fabric that were attached with thread on one end and a gold button on the other.

The trousers worn by the 14th were very similar to that of the Zouave pantaloons, the only difference being that they were not as baggy as the Zouave pantaloons. The color was a vibrant red color. At the bottom of the trousers the 14th wore gaiters or leggings with seven gold buttons on each gaiter symbolizing the number 14.

Sometime in 1862, Colonel E.B. Fowler wrote a letter home commenting on the regiment, a bit about the uniforms, and the tactics in which he had to use. It was later placed in the regimental history.

"In 1860 the Board of Officers adopted the French 'chasseur' uniform, consisting of ashy red trousers, white leggings, a blue jacket, red chevrons and shoulder knots. A fixed to the head was to be a french style kepi with blue band, red above and blue top.

This change of uniform for the regiment was the first in many progressive steps of conformity. Later in early 1861 when the regiment arrived in Washington these improvements were matched by the introduction of the rifled musket and minie ball which took the place of the smooth bore with its round ball and buckshot.

A mixture of Gilhams' Militia Tactics and Hardee's translation of the French tactics were substituted for the old Scott "heavy infantry" tactics as well as its accompaniment of leather stock and pipe clayed belts.

Little did the officers of that board dream that the uniform that they then adopted would become historic, sung of in poets' lays and transferred to the artist's canvas as that of the "red-legged devils," the Brooklyn Fourteenth."[2]

First Bull Run

At the First Battle of Bull Run, the 14th Brooklyn was assigned to the First Brigade (commanded by Col. Andrew Porter) in Col. David Hunter's Second Division in General Irwin McDowell's Army of Northeastern Virginia. The Regiment was ordered up to Henry House Hill to reinforce the 1st Minnesota Volunteer Infantry Regiment and the 11th New York Volunteer Infantry Regiment, the "Fire Zouaves". These regiments had been ordered to support two batteries of cannon under the command of Captains Charles Griffin and James B. Ricketts on the Union right flank. Before the arrival of the 14th Brooklyn at Henry House Hill, the 11th New York had withdrawn to the Manassas-Sudley Road under heavy assault and then fought off a flank attack from Confederate Colonel J. E. B. Stuart's cavalry. As the 14th Brooklyn moved up the hill, the 11th New York rallied and joined with the 14th to support the guns. Colonel Stuart's subordinate W. W. Blackford wrote this account in his memoir, "War Years with Jeb Stuart" (from page 28):

"Colonel Stuart and myself were riding at the head of the column as the grand panorama opened before us, and there right in front, about seventy yards distant, and in strong relief against the smoke beyond, stretched a brilliant line of scarlet - a regiment of New York Zouaves in column of fours, marching out of the Sudley road to attack the flank of our line of battle. Dressed in scarlet caps and trousers, blue jackets with quantities of gold buttons, and white gaiters, with a fringe of bayonets swaying above them as they moved, their appearance was indeed magnificent."[8]

The 14th Brooklyn, 11th New York, and 1st Minnesota were placed into position by Major William Farquhar Barry, McDowell's chief of artillery, at the crest of Henry House Hill. They were ordered to hold their position and assault if the opportunity was there, but were under no circumstances to leave the guns to the Confederates. The three regiments and cannon found themselves confronting the 33rd Virginia Infantry on the left of Confederate General Thomas J. "Stonewall" Jackson's line.

Confusion soon erupted on the battlefield in front of them. Thinking the 33rd Virginia, clad in dark blue frock coats and dark blue trousers, were the Union troops supporting the guns, Major Barry ordered Ricketts to hold his fire. This allowed the Virginians to charge the batteries and capture the guns. The 14th Brooklyn, however, rushed up the slope and drove the 33rd Virginia back, recapturing the two guns. The 14th then continued to fire into the left flank of Jackson's line, driving the 33rd Virginia back through the 2nd Virginia Infantry. Under the pressure from the 14th Brooklyn, a large portion of the 2nd Virginia joined the retreating 33rd Virginia and the left of Jackson's line began to collapse. However, Jackson ordered the 4th and 27th Virginia forward. They were joined by the 49th Virginia Infantry, two companies of the 2nd Mississippi Infantry, and the 6th North Carolina Infantry. In hand-to-hand combat the New Yorkers were driven back to the Manassas-Sudley Road and Ricketts' battery and Griffin's two guns captured.[9]

The 14th Brooklyn, the 69th New York Militia and 11th New York would charge up Henry House Hill four times, in an effort to recapture Ricketts' and Griffin's cannon. The other two regiments met with little success, but the 14th Brooklyn found gaps and weaknesses in the Confederate lines and exploited them. The 14th Brooklyn briefly took control of the two guns following one charge, only to be routed yet again by the Confederates. The constant charging of the 14th Brooklyn's tactics caught the eye of General Jackson himself. This is when he made his famous statement to his troops: "Hold on Boys! Here come those Red Legged Devils again!" With that the regiment received its nickname the "Red Legged Devils".

While the 14th Brooklyn and 11th New York Volunteer Infantry were briefly in control of the two guns, the Louisiana Tigers advanced up the hill. The 14th and 11th fired upon the battalion from their superior position, causing significant losses. The Tigers then fired their own rifles, and the majority of the 14th fell to their knees. Encouraged by this, the Tigers dropped their rifles and took out their Bowie knives in an attempt to finish off the survivors. As the Tigers neared the crest of the hill, the 14th Brooklyn stood up. Though both the 14th Brooklyn and the Tigers, who had left their rifles at the bottom of the hill, were poorly trained and lacked real wartime experience, a savage hand-to-hand fight began between the two units. Though the Tigers fought with ferocity and determination, the 14th Brooklyn had the superior field position and eventually the Tigers retreated back down the hill. This brief confrontation permanently made the 14th Brooklyn and the Tigers rivals.

.jpg.webp)

The efforts of the 14th Brooklyn, however, were in vain, and they were immediately flushed from the position yet again by the powerful Confederate counterattack. The two guns would not be retaken again. As the Confederates launched their strong counterattack, the Union army panicked and fled. They had been startled by the fierce, brutal fighting that the Confederates had brought, it being completely unlike the riot quelling they had performed in the past. It is local legend that the 14th Brooklyn refused to flee with such blind abandon as the rest of the Union army, but rather were ordered off the field, but this has not been corroborated by any contemporary records.

During the battle, the 14th Regiment suffered two officers and 21 men killed, 64 wounded, and 30 taken prisoner. Ten of the wounded would die of their wounds. Colonel Wood himself was wounded and captured by the enemy.[5]

After the First Battle of Bull Run, the State of New York decided to change the regiment's designation from 14th State Militia to 84th New York Volunteer Infantry. The men of the regiment were displeased and began a letter campaign, joined by the citizens of Brooklyn. Finally the men asked the help of General Irvin McDowell. McDowell spoke to the government and to the regiment's command, and his words bestowed upon the regiment the motto which would follow it throughout history:

"You were mustered by me into the service of the United States as part of the militia of the State of New York known as the Fourteenth. You have been Baptized by Fire under that number and as such you shall be recognized by the United States government and by no other number"[10]

Second Bull Run to Antietam

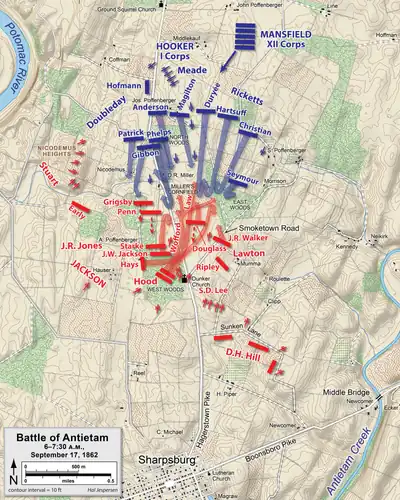

At Second Bull Run the regiment again fought courageously, losing nearly 120 men. At Antietam, the 1st Division commanded by Brigadier General Abner Doubleday of the 1st Corps began their attack on the morning of 17 September 1862 from the North Woods. Col. Walter Phelps' Iron Brigade fought through the Miller Farm's cornfield. Both Union and Confederate casualties at the cornfield were roughly 6,000. It was at the cornfield that famed nurse Clara Barton went onto the actual battlefield to help the wounded soldiers of the Union Army. According to a report from William Fox of the 107th New York, the brigade that composed of the 22nd New York, 24th New York, 30th New York, 14th Regiment (New York State Militia), and 2nd U.S. Sharpshooters was the first to be called the "Eastern Iron Brigade" because of its brave fighting at South Mountain and Antietam. Colonel Rufus R. Dawes the commander of the Sixth Wisconsin later wrote in his book "Service with the Sixth Wisconsin Volunteers":

"The Fourteenth Brooklyn Regiment, Red legged Devils, came into our line closing the awful gaps. Now is the pinch. Men and officers of New York and Wisconsin are fused into a common mass, in the frantic struggle to shoot fast. Everybody tears cartridges, loads, passes guns, or shoots."[11]

In the cornfield, the Eastern Iron Brigade followed the Western Brigade into battle early in the morning. While the rest of Phelp's brigade fell back, the 14th Brooklyn held its ground along with elements of the 6th Wisconsin of the Black Hats (Western Iron Brigade). This effort combined into a mass of soldiers pushing the Confederates up to Dunker Church. These two regiments got further than any other Union Regiment during the attack in the cornfield.

Fredericksburg to Chancellorsville

At Fredericksburg and Chancellorsville the 14th Brooklyn saw minor action during the major engagements. The regiment was held in reserve and then used for a series of reconnaissance missions to find and assault the Confederate forces in and around the area. It was during this campaign that the Brigade proved that they truly were the "Iron Brigade of the East" During Chancellorsville the regiment saw a quick but highly deadly action alongside the Sixth Wisconsin in the Battle of Fitzhugh's Crossing. The 14th held the riverbank as the sixth Wisconsin attempted to cross the river in small wooden boats. It was after this campaign a little before the Battle of Gettysburg that the 14th and all the other regiments in the 1st Corps, 1st Division, 1st Brigade were transferred out. The 14th was transferred to the 1st Corps, 1st Division, 2nd Brigade.

Gettysburg to Spotsylvania

The 14th Brooklyn was the last regiment of the 2nd Brigade on the road to Gettysburg. The 2nd Brigade were the first Infantry units to fire their rifles and to set foot on the field 1 July 1863. General John F. Reynolds rode up to the 2nd Brigade and urged them onto Gettysburg to support General John Buford's cavalry who were holding the Confederate forces at bay. The 14th dropped its packs on the Emmitsburg road and double quicked across the field that General Pickett's men would on 3 July.

The 14th Brooklyn arrived at McPherson's Woods and halted the Confederate advance, until the 1st Brigade of the 1st division arrived. Once the Western Iron Brigade was online, Colonel E.B Fowler saw Confederate forces taking cover in an unfinished railroad cut to his right. He commanded his "Demi-Brigade" (14th Regiment & 95th NYVI) across the field to meet and clear out Davis' Confederate Brigade. Held in reserve the 6th Wisconsin was ordered to support the 14th regiment and 95th NYVI into the cut. Again the 14th and 6th were together working as they did in earlier engagements.

Into the cut the three regiments rushed, supporting each other equally on each other's flanks. One 14th Brooklyn soldier said of the Confederate defense of the railroad cut "they fought with the ferocity of wildcats" the fight became a brawl of hand-to-hand combat.[2] The Federals who had taken a beating crossing the field in front of the railroad cut had their revenge. The Confederates facing them finally realized their position was a death trap and surrendered themselves to Colonel E.B. Fowler, and handed their Flags over to the 14th Brooklyn. Finally the Confederates were able to wheel artillery down and fire on the 14th's Position in the railroad cut, the 14th marched out of the cut through the town of Gettysburg while the 11th corps came up to support the 1st corps so they could refit. The 14th Brooklyn had the honor of carrying General John F. Reynolds' body from the field into the town of Gettysburg.

The regiment continued to fight for the remainder of the battle of Gettysburg. They are the only regiment to possess 3 monuments on the field of Gettysburg - at the railroad cut, at McPherson's woods and on Culp's Hill. The remainder of the fight was had on Culp's Hill on the right flank of the Union army. They were called up to support General Greene who was losing his position to superior numbers. The 14th Brooklyn fought 2 days up there, and Greene later credited the 14th Brooklyn for helping save the entire Union army by saving the flank.

In the early hours of 2 July 1863 the 14th Brooklyn was called down to the slope of Culp's Hill. Lt. John J. Cantine, one of General Greene's aides, met the regiment and guided Col. Edward B. Fowler and the regiment to its position on the right of Greene's line. As Cantine led fowler by some trees, a soldier stepped from the darkness and demanded Cantine's surrender. Cantine dismounted from his horse and Fowler drew his pistol, and then there were a dozen or so shots from the woods. Fowler hurried back to the regiment and formed it facing the woods. Fowler then called for volunteers to scout the woods and report back, who may be at his front. Two men, musician John Cox and Sgt. James McQuire of company I, responded and disappeared into the woods or, as one 14th Brooklyn Member recounts "in the teeth of flank fire", to find out who was there. Cox returned with the word that McQuire had been wounded and that the troops in their front of them belonged to the 10th Virginia Regiment. Colonel Fowler then ordered the regiment to fire a volley and thus charged his regiment into the woods. Hand-to-hand fighting began, and the 14th Pushed the Virginians out of the woods and sent them into a retreat.

Lt. Henry H. Lyman who wrote of the regiment in his diary:

"14th & 147th go among the 12th corps to help drive back the charging rebs. Hot work from 1/2 past 5 to 1/2 past 9. Lie in the pits all night on our arms. No pickett in front."[12]

The 14th Brooklyn was called back up the hill after this action being relieved by the 137th Ny. They were there long enough to eat some food and then were immediately sent back down the hill to support the hill once again. Colonel Fowler wrote that when the men entered the trenches "they did so without a shout, and the regiment remained there until their ammunition was all but exhausted." He also recounted the casualties taken with the trenches were light but that the colors, which rose above the works, were riddled with bullets, and the staff of the state flag was shot through.[2]

On 3 July, the 14th Brooklyn's Position was further up the hill near the 149th New York. When the men of the 149th New York had heard that the 14th Brooklyn were coming down they studied them closely. Prior to this the men of the 149th had heard that the 14th Brooklyn were "a bully fighting regiment" what they saw were young men with a "tidy and smart appearance". In Later years the regiment was credited with saving the line and thus saving ammunition trains as well as the flank.[12]

The 14th Brooklyn Fought for another year, through the Battle of the Wilderness campaign and Spotsylvania. They finally mustered out in May 1864. The recruits who signed up and joined the regiment in 1862 were moved over to the 5th New York Veteran Volunteer Infantry Regiment. However, the recruits who went over to the 5th New York Veterans (Duryea Zouaves)wore their 14th Brooklyn uniform and formed their own company in the 5th. The regiment mustered out at Fulton Ferry on 25 May 1864 to huge crowds who welcomed the regiment home after 3 years of service. During its 3 years in service the regiment sustained 717 casualties, nearly 41% of its men.[2]

Nicknames and other designations

- 84th New York Volunteer Infantry Regiment

- Fourteenth Regiment, N.Y.S.M (New York State Militia)

- Red Legged Devils

- 14th Brooklyn

- Lincoln's Pups

- Brooklyn Phalanx

- Brooklyn Chasseurs

- Chasseurs a Pied (French for Hunters on Foot)

- The Fighting 14th

- Brooklyn Zouaves

- Brooklyn Red Legs

Officers of the 14th Brooklyn

- Colonel Edward Brush Fowler

- Colonel Alfred M. Wood

- Colonel Ardolph L. Kline

- Lt. Colonel William H. DeBevoise

Captain-Brevet Major Isaiah Uffendill

After the American Civil War

Since the regiment's return from the battlefields of the American Civil War, the 14th was twice involved in service, first during the quarantine disturbances at Fire Island in September 1892, and throughout the Brooklyn motormen's strike in January 1895. The 14th was one of the few regiments selected in General Orders, No.8, General Headquarters, State of New York, dated Adjutant General Office, Albany, 27 April 1898, to enter United States Military service. At that time the regiment consisted of ten companies. Upon receiving this order the regiment began recruiting to fill these companies as well as organize two additional ones.

The 14th Regiment, Infantry, New York Volunteers was mustered into the service in May 1898 take part in the Spanish–American War. The regiment was in Federal service for only four months and was detailed to camp service. The 14th did not reach the front lines, but made preparations for duty in Cuba, and the soldiers were in a "fine state of organization". All of the 14th's officers and men were anxious to be involved the real fighting on the front lines, but this movement was deemed unnecessary by the government after considerable thought.

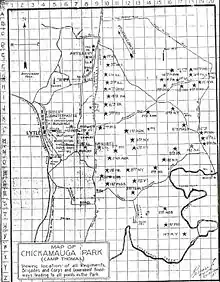

On 1 May, the regiment was ordered to camp at Hempstead, Long Island New York. The regiment then reported to Major General Charles F. Roe, who was in command of the National Guard. The 14th then mustered into service as follows: Companies A, G, K, and M on 13 May; the rest of its companies on 16 May. On 17 May, the regiment left Hempstead and proceeded by rail to Camp George H. Thomas, Chickamauga, Georgia. The regiment arrived and was assigned to the First Brigade, First Division, Third Army Corps on 29 May.

On 5 September, the 14th Infantry received orders to muster out on corner of Eighth Avenue and Fifteenth Street, Brooklyn at the armory. The men of the 14th left Anniston on 14 September and arrived in Brooklyn on 16 September. In 1893, the Eighth Avenue Armory was constructed for the regiment. They were mustered out United States service on 27 October 1898.

The regiment entered the Spanish–American War as the 14th New York Infantry and many sons of veterans who fought during the American Civil War with the 14th Brooklyn enlisted with the 14th New York Infantry. Following the Spanish–American War, 14th New York Infantry troops reinforced the 106th Infantry and fought in World War I.[13]

Legacy of the Red Legged Devils

Following the conclusion of the war, members of the 14th Regiment New York Veterans Association continued to hold monthly meetings. Several battlefield memorials were erected over time. Today members of reenactment units do the same to preserve the honor and memory of the 14th Brooklyn.

The 14th Brooklyn Co. E reenactment group at Remembrance Day in Gettysburg

The 14th Brooklyn Co. E reenactment group at Remembrance Day in Gettysburg Col Fowler's statue in Fowler Square

Col Fowler's statue in Fowler Square Capture of a rebel brigade, July 1st 1863 memorabilia

Capture of a rebel brigade, July 1st 1863 memorabilia

See also

- 14th Regiment Armory, Brooklyn (also known as the "Eighth Avenue Armory" and the "Park Slope Armory")

- List of armories and arsenals in New York City and surrounding counties

- List of New York Civil War regiments

References

Notes

- "A Short Regimental History of the 14th Brooklyn". Fourteenth Brooklyn Regiment, N.Y.S.M., Co.E, Living History Association. Archived from the original on 28 August 2008. Retrieved 6 September 2008.

- Tevis, C. V.; D. R. Marquis (1911). The History of the Fighting Fourteenth: Published in Commemoration of the Fiftieth Anniversary of the Muster of the Regiment Into the United States Service, May 23, 1861. New York, NY: Brooklyn Eagle Press.

- "Brooklyn Chasseurs, "Red Legged Devils", 14th Infantry Regiment". New York State Military Museum. Retrieved 6 September 2008.

- "The Firemen's Riot 1853 and The Angel Gabriel Riot 1854". The Riots of New York City. The History Box. Archived from the original on 28 August 2008. Retrieved 7 September 2008.

- "14th Regiment History". New York State Military Museum. Retrieved 7 September 2008.

- "Duryee's Zouaves". zouave.org. Archived from the original on 9 December 2013. Retrieved 27 May 2014.

- "[Unidentified soldier in Union Zouave uniform with bayoneted musket with initials A.T. on stock]". loc.gov.

- "Stuart's Report...and "Zouaves"! (From The Book: War Years with Jeb Stuart) P. 28". Bull Runnings. Archived from the original on 14 March 2008. Retrieved 23 March 2008.

- Ted Ballard (2004). "First Bull Run: An Overview". Staff Ride Guide: Battle of First Bull Run. United States Army Center of Military History. pp. 27–28. Archived from the original on 9 October 2008. Retrieved 5 September 2008.

- "History of the Fighting Fourteenth". Tevis & Marquis. Archived from the original on 28 August 2008. Retrieved 5 November 2007.

- Service with the Sixth Wisconsin, Rufus Dawes (P. 90). E.R. Alderman & Sons. 1890.

- Harry Willcox Pfanz (31 May 2001). Culp's Hill and Cemetery Hill. ISBN 9780807849965.

- "106th NY Infantry Regiment during World War One - NY Military Museum and Veterans Research Center". state.ny.us.

Bibliography

- The History of the Fighting Fourteenth, Tevis & Marquis.

- Cutler's Brigade at Gettysburg, James L. McLean, 1995

- Reports by the Gen. S.E. Marvin, Adjutant-General S.N.Y.

- Service with the Sixth Wisconsin Volunteers by Lt. Colonel Rufus Dawes

External links

- "The Red Legged Devil" Historical Research Blog dedicated to the Fourteenth Brooklyn

- 14th Brooklyn Historical Association History, table of battles and casualties, Civil War newspaper clippings, Letters, national flag and regimental flag for the 14th Regiment (New York State Militia), and Full Rosters.

- State of New York Civil War Records Website

- State of New York 14th Brooklyn

- Rootsweb Regimental Information Website