Red Sport International

The International Association of Red Sports and Gymnastics Associations, commonly known as Red Sport International (RSI) or Sportintern was a Comintern-supported international sports organization established in July 1921. The RSI was established in an effort to form a rival organization to already existing "bourgeois" and social democratic international sporting groups. The RSI was part of a physical culture movement in Soviet Russia linked to the physical training of young people prior to their enlistment in the military. The RSI held 3 summer games and 1 winter games called "Spartakiad" in competition with the Olympic games of the International Olympic Committee before being dissolved in 1937.[1]

Organizational history

Background

The notion of a separate working class national athletic federation emerged first in Germany during the decade of the 1890s, when a Workers Gymnastics Association was established by activists in the socialist movement in opposition to the nationalist German Gymnastics Society (Turnen).[2] Other "proletarian" sports organizations emerged soon thereafter in that country, including the Solidarity Worker Cycling Club, the Friends of Nature Rambling Association, the Worker Swimming Association, the Free Sailing Association, and the Worker Track and Field Athletics Association, among others.[2] By the time of World War I, the German proletarian sports movement included more than 350,000 participants.[2]

Following the bloodbath of World War I, the German workers' sports movement began to reemerge, with a new competitive orientation beginning to take the place of individualistic club activities.[2] The international social democratic movement also experienced a rebirth after its connections had been severed by war. In 1920 the social democrats established an International Association for Sports and Physical Culture, echoing its efforts in the pre-war period.[2] This organization was rechristened as the Socialist Workers' Sport International (SWSI) in 1925.[2]

In the aftermath of the Russian Revolution of 1917 the international socialist movement divided into two antagonistic camps, socialist and communist — a division exacerbated with the establishment of the Communist International (Comintern) in 1919. Parallel political organizations sprung up in every country and a state of bitter enmity prevailed.

Establishment

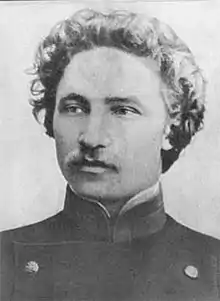

The idea of a rival Red Sport International (RSI) was the inspiration of Nikolai Podvoisky, who at the 2nd World Congress of the Comintern in the summer of 1920 discussed with a number of delegates from around the world the idea of establishing an organization to coordinate the physical training of youth.[3] Podvoisky, a military specialist in charge of Soviet Russia's military training organization, believed systematic physical training to be beneficial for the needs of the Red Army for healthy and fit youth in its ranks.[3] An international sports organization was also seen as a potential ideological counterweight to the Olympic games of the "bourgeois" International Olympic Committee as well as the activities of the rival International Association for Sports and Physical Culture of the socialists.[4]

Podvoisky gathered interested delegates who were already in Moscow for the Comintern Congress and the group constituted itself a founding conference for an international sports organization.[3] It is worthy of emphasis that the Comintern did not itself directly found the Red Sport International, the group being established through independent initiative and the Comintern being preoccupied with other affairs.[5] The group issued a public manifesto declaring the establishment of a Red Sport International and elected a governing Executive Committee, consisting of representatives from Soviet Russia, Germany, Czechoslovakia, France, Sweden, Italy, and Alsace-Lorraine.[3] Podvoisky was elected President of the new organization.[3]

The establishment of an international sports organization in Soviet Russia in 1921 was not without its utopian elements, since no official Soviet sport organizations existed in famine stricken post-civil war Soviet Russia at that time.[6] Germany, on the other hand, had a well-developed workers' sport movement at this time.[4] Consequently, Sportintern from its outset maintained a strong German flavor and it was there in the city of Berlin that the 2nd Conference of the organization was held in July 1922.[4] The only national "proletarian" sports organization to join the German group at that early date was the Czechoslovak Federation of Workers' Gymnastic Leagues, said to represent 100,000 athletes.[4]

The Comintern moved closer to the fledgling Sportintern in November 1922 when, in conjunction with the 4th World Congress, the governing Executive Committee of the Communist International decided to name a representative to the "independent" proletarian sport organization.[4] The Communist International of Youth (KIM) did not take action until the meeting of its governing Bureau in Moscow in July 1923, when it issued a general recommendation of support for the Sportintern and the national sports organizations affiliated to it as a useful "proletarian class instrument."[7] It did not, however, delve into the contentious issue of in what manner and to what extent these two international bodies should be related.[7]

The governing Executive Committee of Sportintern met in Moscow in February 1923 and decided to establish a satellite bureau of the organization in Berlin, with a view to increasing participation among Western European workers' sports organizations.[8] The maneuver proved successful in helping to build the organization, triggering a split of the French Workers Sports Federation later that year and the affiliation of 80% of its membership with the Red Sport International.[9] The RSI's increased place in the public eye motivated the governing body of the rival international socialist sports authority, meeting in Zurich in August 1923, to discuss issuing an invitation to Sportintern to help organize a joint "Workers' Olympiad" — a proposal which was narrowly defeated, despite indications that a majority of individual members of the socialist organization favored joint participation.[9]

End of autonomy

In October 1924 the Red Sport International held its 3rd Congress in Moscow.[10] At this time the organization decided to enlarge its governing Executive Committee to include four members of the executive committee of the Communist International of Youth — an organization which saw the national affiliates of Sportintern as comprised overwhelmingly of young workers and sought to insert its influence in the organization.[10] As the membership of Sportintern was formally "open to all proletarian elements which recognize the class struggle" it was not an explicitly communist organization, a situation which the KIM saw as a significant shortcoming.[10]

The RSI was a large and growing organization in this interval, with some 2 million affiliated members in the Soviet Union, joined by others sections in Germany, Czechoslovakia, France, Norway, Italy, Finland, Switzerland, the United States, Estonia, Bulgaria, and Uruguay.[11] As the size of the organization grew, so, too, did pressure to bring the organization's ideological character under tighter centralized Communist Party control.

Nikolai Podvoisky was himself a voice for such an insertion of such ideological hegemony, declaring in a lengthy speech to the 5th Enlarged Plenum of the Comintern, held in the spring of 1925, that Sportintern should henceforth adopt as its motto:

"Convert sport and gymnastics into a weapon of the class revolutionary struggle, concentrate the attention of workers and peasants on sport and gymnastics as one of the best instruments, methods, and weapons for their class organization and struggle."[12]

At the same time the international communist movement moved to further politicize the RSI, efforts were made to make political hay over the refusal of the Socialist Workers' Sport International to conduct joint activities, such as its decision to bar the Red Sport International from participation at the July 1925 "Workers' Olympiad" held in Frankfurt under its auspices.[13]

It was in this period, 1924 to 1925, that the Red Sport International effectively became an auxiliary of the Communist International.[14] This control was effected by the subordinate youth section of the Comintern, the Communist International of Youth, although the Comintern reserved for itself ultimate authority to decide issues of great importance.[15] As the Comintern was itself in the process of being absorbed as an instrument of Soviet foreign policy in this interval, the RSI likewise gradually lost its ability to function independently as an international entity.[15]

In the words of French sports historian André Gounot:

"...The RSI's dependence on the Comintern was accompanied, almost inevitably, by the Soviet section's dominance within the RSI. The interests of the Soviet Union and Soviet sport were decisive factors in the RSI's decisions and actions — even if, as was frequently the case, they were incompatible with those of European worker sport."[15]

The last International Congress of the Red Sport International came in 1928 and was marked by no serious discussion of contemporary sporting issues.[16] Instead the 1928 gathering consisted of a mechanical attempt to apply the Comintern's ultra-radical Third Period slogan of "Class versus Class" and its corollary theory of social fascism to world sport — splitting the fissure between the two camps of the European workers' sport movement wider than ever.[16]

Social composition

Membership of the various national sections of the Red Sport International was by no means monolithic. According to the RSI's own study of the issue, members of the organizations were predominantly male, but hailed from a variety of communist, socialist, syndicalist, and anarchist tendencies, including many of whom who were members of no party.[17] Although many of these were of the working class, also included were white collar employees, students, and government workers.[17] Membership records of the French section, for example, indicate that approximately 80% of participants were from the working class, with the remaining 20% members of other social groups.[18]

No details exist for the exact Communist Party membership of any national section of the RSI, although in the considered opinion of a leading historian on the topic, "it is safe to assume that this group represented a minority of the whole membership of each section."[19] The Czechoslovakian federation, thought to include the largest Communist Party contingent from outside the USSR, is believed to have included something in the range of 20 to 30% who were members of the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia.[19]

The fact that members of other parties or no parties participated in the national sections of the Red Sport International is testimony to the limited impact that RSI programmatic rhetoric had upon grassroots participants.[19] It was rather the fun and excitement of training and competition that bound together local groups and their national units more than ideological proclivities.[19] The difference in perception of the organization between its rank-and-file participants and the Moscow dominated leadership of the organization has led one scholar to conclude that the RSI was a "split organization, living in two universes," bureaucratic in political discourse but remaining well within the less intense social democratic workers' sports tradition at the individual club level.[20] In this view politics was merely a piece of a broader participatory sports movement.[20]

International competitions

The international workers' sports organizations of the socialist and communist movements did not necessarily object to some of the most noble goals of the International Olympic Committee (IOC),[21] but they did each share fundamental reservations about the modern Olympic games that were the inspiration of Baron Pierre de Coubertin, a hereditary French nobleman.[22] First and foremost, the Olympics of the IOC stressed competition between nations — regarded by the radicals as a manifestation of national chauvinism.[21] Rather than the accentuation of national rivalry and patriotic feeling, international competition should focus on the actual athletic effort in a setting designed to build the ethic of internationalism, both the socialists and communists agreed.[21]

The IOC games also were based upon rigid entrance standards, while the international festivals of the worker athletic movement instead attempted to build mass participation through pageantry, artistic and cultural activities, and unifying political presentations.[21] Moreover, the sort of athletes dominating the IOC games were objectionable to the radicals on the basis of social class, dominated as they were by the privileged children of the rural aristocracy and the bourgeoisie.[21] Such international competitions should be open to the participation of less privileged national and social groups, without distinction to race or creed, in the view of the radical sports organizations.[21]

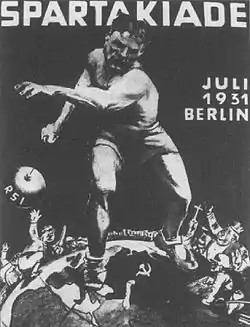

Therefore, the Red Sport International and its socialist rival, the organization emerging as the Socialist Workers' Sport International, conducted a series of their own workers' sports festivals in distinction to and competition with the Olympiads of the IOC. Four such events (called Spartakiads in honor of the heroic slave leader, Spartacus) were sponsored by the RSI. Two of these were held in 1928, and one each in 1931 and 1937.

While a major national workers' sport festival had already been held in Czechoslovakia in 1921, it was the socialist organization in 1925 that conducted the first pair of Workers' Olympics events — Summer Games in Frankfurt attracting 150,000 spectators and competitors from 19 country, and Winter Games in Schreiberhau (today's Szklarska Poręba, Poland), attended by athletes from 12 countries.[23] No national flags or anthems graced the closing or opening ceremonies, replaced instead by universal use of the red flag and singing of "The Internationale."[23] "Soviet and other communist athletes were excluded from these games, however, and there was therefore little actual unity of the workers' sports movement for all the universalist pageantry employed.

From the middle 1930s the political line of the world communist movement changed. The so-called Popular Front against the threat of fascism rendered cooperation with socialists and others through unified workers' athletic festivals not only a possibility but the tactical order of the day. Plans were laid for a so-called 3rd Workers' Olympiad to be held in Barcelona, Catalonia, Spain in June 1936, under joint auspices of the RSI and the SWSI. The time and place proved inauspicious, however, coinciding with outbreak of hostilities in the Spanish Civil War.[24] This forced postponement of the event, which was rescheduled for the next summer in Antwerp, Belgium.[24]

The 3rd Workers' Olympiad proved to be less successful than previous endeavors, but it still managed to attract 27,000 participating athletes, and put 50,000 people in the stadium for the final day of competition.[24] An estimated 200,000 people turned out for the traditional closing parade through the city.[24]

Dissolution

With the Soviet Union becoming immersed in the first months of 1937 in a massive and xenophobic secret police campaign against perceived underground espionage networks remembered as the Great Terror, the Red Sport International was summarily dissolved by the Comintern in April of that year.

List of Spartakiads

| Event | Location | Date | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1st Summer Spartakiad | Moscow | 1928 | |

| 1st Winter Spartakiad | Oslo | 1928 | |

| 2nd Spartakiad | Berlin | 1931 | |

| 3rd Workers' Olympiad | Antwerp | 1937 | Held jointly with the international Socialist sport organization. |

Gatherings of the RSI

- Source: Gounot, "Sport or Political Organization?" pg. 28.

| Event | Location | Date | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1st Conference | Moscow | July 19–29, 1921 | |

| 2nd Congress | Berlin | July 29–31, 1922 | |

| 1st Enlarged Plenum of the EC | Moscow | Feb. 7–13, 1923 | |

| 3rd Congress | Moscow | Oct. 13–21, 1924 | |

| 2nd Enlarged Plenum of the EC | Moscow | Jan. 28, 1925 | |

| 3rd Enlarged Plenum of the EC | Moscow | May 17–22, 1926 | |

| 4th Enlarged Plenum of the EC | Moscow | Nov. 10–16, 1927 | |

| 4th Congress | Moscow | Oct. 23–24, 1928 | |

| 5th Enlarged Plenum of the EC | Kharkov | May 31-June 2, 1929 | |

| 6th Enlarged Plenum of the EC | Berlin | July 14–17, 1931 | |

| RSI Conference | Amsterdam | Sept. 2–3, 1933 | |

| RSI Conference | Prague | March 7–8, 1936 |

See also

Footnotes

- Barbara J. Keys. The Soviet Union and the Triumph of Soccer. Globalizing Sport. "Harvard University Press", 2006. ISBN 0674023269

- James Riordan and Arnd Krüger, The International Politics of Sport in the Twentieth Century. London: Routledge, 1999; pg. 107.

- E.H. Carr, A History of Soviet Russia: Socialism in One Country, 1924-1926: Volume 3, Part 2. London: Macmillan, 1964; pg. 957.

- Carr, Socialism in One Country, 1924-1926, vol. 3, pt. 2, pg. 958.

- André Gounot, "Sport or Political Organization? Structures and Characteristics of the Red Sport International, 1921-1937," Journal of Sport History, vol. 28, no. 1 (Spring 2001), pg. 23.

- Carr, Socialism in One Country, 1924-1926, vol. 3, pt. 2, pp. 957-958.

- Carr, Socialism in One Country, 1924-1926, vol. 3, pt. 2, pg. 960.

- Carr, Socialism in One Country, 1924-1926, vol. 3, pt. 2, pp. 960-961.

- Carr, Socialism in One Country, 1924-1926, vol. 3, pt. 2, pg. 961.

- Carr, Socialism in One Country, 1924-1926, vol. 3, pt. 2, pg. 963.

- Carr, Socialism in One Country, 1924-1926, vol. 3, pt. 2, pp. 963-964.

- Quoted in Carr, Carr, Socialism in One Country, 1924-1926, vol. 3, pt. 2, pg. 963.

- Carr, Socialism in One Country, 1924-1926, vol. 3, pt. 2, pg. 965.

- Gounot, "Sport or Political Organization?" pg. 25.

- Gounot, "Sport or Political Organization?" pg. 27.

- Gounot, "Sport or Political Organization?" pg. 28.

- Internationaler Arbeitersport: Zeitschrift für Fragen der internationalen revolutionären Arbeitersportbewegung. Aug. 1931, pg. 303. Quoted in Gounot, "Sport or Political Organization?" pg. 29.

- Gounot, "Sport or Political Organization?" pg. 38, fn. 29.

- Gounot, "Sport or Political Organization?" pg. 29.

- Gounot, "Sport or Political Organization?" pg. 35.

- Riordan and Krüger, The International Politics of Sport in the Twentieth Century, pg. 109.

- Christopher R. Hill, Olympic Politics: Athens to Atlanta, 1896-1996. Manchester, England: Manchester University Press, 1996; pg. 5.

- Riordan and Krüger, The International Politics of Sport in the Twentieth Century, pg. 110.

- Riordan and Krüger, The International Politics of Sport in the Twentieth Century, pg. 113.

Further reading

- Pierre Arnaud and James Riordan, Sport and International Politics: The Impact of Fascism and Communism on Sport. Taylor & Francis, 1998.

- Barbara Keys, "Soviet Sport and Transnational Mass Culture in the 1930s," Journal of Contemporary History, Vol. 38, No. 3, (July 2003), pp. 413–434.

- Nikolai Podvoisky, (article on the establishment of RSI), Pravda, October 15, 1924.

- James Riordan, Sport, Politics, and Communism. Manchester, England: Manchester University Press, 1991.

- David Alexander Steinberg, Sport under Red Flags: The Relations between the Red Sport International and the Socialist Workers' Sport International, 1920-1939. PhD dissertation. University of Wisconsin — Madison, 1979.

- David A. Steinberg, "The Worker Sports Internationals, 1920-28," Journal of Contemporary History, vol. 13, no. 2 (April 1978), pp. 233–251.

- Robert Wheeler, "Organized Sport and Organized Labor: The Workers' Sports Movement," Journal of Contemporary History, vol. 13, no. 2 (April 1978), pp. 191–210.

- (Proceedings of the July 1921 Conference), Internationale Jugend-Korrespondenz, No. 7 (April 1, 1922), pg. 11.

External links

- Red Sport International at sport-history.ru. from Encyclopedic dictionary on physical culture and sports. Volume 2. Chief editor G.I.Kukushkin. Moscow, "Fizkultura i sport", 1962. page 388 (Энциклопедический словарь по физической культуре и спорту. Том 2. Гл. ред.- Г. И. Кукушкин. М., 'Физкультура и спорт', 1962. 388 с.)